Understanding the Rise of Dominicans in Major League Baseball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrating the Amazing in Special Needs!

Celebrating the Amazing in Special Needs! Gillette Stadium, Putnam Club Leading Sponsorship Provided by Hosted by Entertainment Keynote Speakers Jordan Rich Bo Winiker Jazz Band Dick & Rick Hoyt of WBZ Radio with Tony Dublois of Team Hoyt Thank You! Table of Contents Live Auction Items ...........................................2 Silent Auction Items Sports Tickets - Red Sox .............................6 Sports Tickets - Patriots ...............................7 Sports Tickets - Bruins ................................8 Sports Tickets - Celtics ................................8 Other Sport Items.........................................9 Hit the Links: Golf Items ...........................10 Fitness - Let’s Get Physical! ......................12 Take Good Care of Yourself ......................12 Entertainment.............................................13 Getaways ...................................................15 Food / Wine / Dine Around........................15 Sports and Entertainment Memorabilia .....17 Sporting .....................................................18 For the Home .............................................19 For the Kids and Family ............................20 What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others. — Pericles 1 3) SKI LOVERS - SPECTACULAR FIVE BEDROOM HOME AT SUNDAY RIVER, MAINE Live Auction Items This stunning single family residence is located in Sunday River’s exclu- sive Powder Ridge area, just 5 minutes from Sunday River’s ski mountain. 1) TWO (2) TICKETS TO BILLY JOEL AT FENWAY PARK WITH This 5 bedroom house provides an exquisite mountain-view spread out OVERNIGHT STAY, WESTIN BOSTON WATERFRONT over three floors of living space with one indoor and one outdoor fireplace. Rock out with one of the greatest! The highly anticipated show marks the Enjoy the outdoor Jacuzzi overlooking the mountains or enjoy some indoor first time Joel will play at Fenway Park, and it will also be his first solo time with the pool table and air hockey table. -

Daily Gazette Indicated a to -_____-- [ILY GAZII1[ *Call a Family Member Who Also Could Be Hazardous to Your Resident Was Charged Over $31 -S

DAILY S GAZETTE Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Vol. 41 - No. 172 -- U.S. Navy's only shore-based daily newspaper -- Wednesday, September It. t8 Benefits to affect future entrants By Mr. Casper Weinberger tion, the Congress, in its recent action on the pending .nthe past few months, there defense authorization bill, has has been considerable specula- mandated a reduction of $2.9 tion about potential changes to billion to the military the military retirement system. retirement fund. At the same The speculation, often well time, the Congress has directed intentioned but ill informed, the Department of Defense to has been based on criticism from submit options to make changes both the public and private in the retirement system for sectors about the perceived future entrants to achieve this generosity of the system. mandated reduction. The Joint Chiefs of Staff and Nonetheless, we will continue I have steadfastly maintained to insist that whatever changes that any recommendation for the Congress finally makes must change must take account of -- not adversely affect the combat first, the unique, dangerous and readiness of our forces, or vital contribution to the safety violate our firm pledges. of all of us that is made by our I want to emphasize to you service men and women: and the again, in the strongest terms, effect on combat readiness of that the dedicated men and women tampering with the effect on now serving and to those who combat readiness of tampering have retired before them, will th the retirement system. be fully protected in any nourrently we must honor the options we are required to absolute commitments that have submit to the Congress. -

Minor League Players League Minor

FRONT OFFICE FRONT MINOR LEAGUE PLAYERS ACOSTA, NELSON — Pitcher Bats: Right Throws: Right Born: August 22, 1997, Maracay, Venezuela Height: 6-3 Weight: 195 Resides: San Mateo, Venezuela Recommended/Signed By: Amador Arias (White Sox). Sox Acquisition: Signed as a free agent, October 20, 2013. Minor League Highlights: 2016: Held right-handers to a .187 (25-134) average … went 2-0 with a 0.95 ERA (2 ER/19.0 IP) in four FIELD STAFF starts in July. 2015: Went 2-1 with a 1.71 ERA (9 ER/47.1 IP) and 44 strikeouts as a starter … held lefties to a .217 ( 20-92) aver- age and righties to a .229 (25-109) mark. 2014: Limited left-handers to a .162 (11-68) average and righties to a .165 (14-85) mark. YEAR CLUB W-L PCT ERA G GS CG SHO SV IP H R ER HR HB BB-I SO WP BK AVG 2014 DSL White Sox 0-4 .000 2.35 14 12 0 0 1 46.0 25 18 12 0 7 28-0 36 8 0 .163 2015 DSL White Sox 2-2 .500 3.27 14 10 0 0 0 55.0 45 26 20 1 7 23-0 51 7 0 .224 2016 DSL White Sox 2-4 .333 2.31 11 11 0 0 0 46.2 36 16 12 1 5 8-0 45 9 0 .205 MINOR TOTALS 4-10 .286 2.68 39 33 0 0 1 147.2 106 60 44 2 19 59-0 132 24 0 .200 ADOLFO, MICKER — Outfielder PLAYERS Bats: Right Throws: Right Born: September 11, 1996, San Pedro De Macoris, Dominican Republic Height: 6-3 Weight: 225 Resides: San Pedro De Macoris, Dominican Republic Recommended/Signed By: Marco Paddy (White Sox). -

December 18, 2014 Espnchicago.Com Cubs Trade

December 18, 2014 ESPNChicago.com Cubs trade Justin Ruggiano to Seattle By Jesse Rogers CHICAGO -- The Chicago Cubs traded outfielder Justin Ruggiano to the Seattle Mariners for minor league pitcher Matt Brazis, the team announced Wednesday. Brazis, 25, is 8-6 with a 2.89 ERA in 100 minor league relief appearances since being drafted in the 28th round by Seattle in 2012. He finished last season at Double-A and struck out 84 while walking only 18 in 72 innings pitched last year. In the short term the move opens a 40-man roster spot for pitcher Jason Motte, who agreed to terms with the Cubs this week, though they haven’t made the signing official yet. In the longer term the Cubs now have a need for a right-handed hitter who could share time in left field with Chris Coghlan. A trade for an impact player like Justin Upton of the Atlanta Braves is unlikely, which leaves the Cubs filling the need with a role player. Jonny Gomes has drawn interest and the Ruggiano move could pave the way for his signing. The Cubs want leadership in the clubhouse and Gomes has a history with new manager Joe Maddon, having played for him after Maddon took over the Tampa Bay Rays in 2006. Gomes won a World Series ring with the Boston Red Sox in 2013. The Cubs still have righties Junior Lake and Matt Szczur on their 40-man roster, but the front office has expressed a need for veteran leadership which would come from outside the organization at this point. -

January 26, 2016 • Cubs.Com, Cubs Shut Down Venezuelan Summer

January 26, 2016 Cubs.com, Cubs shut down Venezuelan summer team http://m.cubs.mlb.com/news/article/162800450/cubs-pull-out-of-venezuelan-summer-league ESPNChicago.com, Good news for Cubs' Joe Maddon: DH not likely coming to NL soon http://espn.go.com/blog/chicago/cubs/post/_/id/36264/good-news-for-cubs-joe-maddon-dh-not-likely- coming-to-nl-soon CSNChicago.com, Why Cubs spent big this winter (and won't be major players next offseason) http://www.csnchicago.com/cubs/why-cubs-spent-big-winter-and-wont-be-major-players-next-offseason -- Cubs.com Cubs shut down Venezuelan summer team By Carrie Muskat CHICAGO -- The Cubs have signed talented prospects such as Gleyber Torres, Willson Contreras, Gioskar Amaya, Jeffrey Baez, Jonathan Mota and Carlos Penalver in recent years from Venezuela. But the difficulties in the country have forced the Cubs to drop their Venezuelan Summer League team this year. Jason McLeod, senior vice president of player development and amateur scouting, said Monday the Cubs are currently looking at their options on how to best operate in Venezuela at this time. The Cubs will continue to run their academy there and use it for scouting purposes as well as a base for the Parallel League, which is a shortened fall league for young players. The Cubs joined the Tigers, who confirmed Monday that they are pulling out of the VSL this year. There were only four teams in the VSL: the Cubs, Tigers, Phillies and Rays. When the Cubs opted out, leaving the league with three teams, the VSL announced it was cancelling the 2016 season. -

Contest Blooms at Arena

Online: thesouthwester.com The @TheSouthwester SouthwesterServing the Southwest and Capitol Riverfront Communities Copyright © 2013 Southwest Neighborhood Assembly, Inc., All rights reserved. January 2013 Circulation 12,000 FREE Published by the Southwest Neighborhood Assembly, Inc. (SWNA) — a non-profit, 501(c)(3) charitable and educational corporation. Patty Stimmel, from Patty Stimmel Floral Designs in Arlington, Janet Flowers arranges her display from Janet Flowers Wedding Jill Medawar from Toulies en Fleur in Washington, D.C. arrang- arranges a hat for her design inspired by Velma’s dress from Arena and Event Designs in Washington, D.C. Photos by Teresa Wood es her display. Stage’s 2009 production of Crowns. Florists arrived early Nov. 30, to arrange and Fifteen local florists competed in “Isn’t She put up their displays. In the afternoon, Molly Contest Blooms at Arena Smith, Barbara Harrison from WRC4, and JC Loverly: Design in Bloom,” a costume-inspired Hayward from WUSA9 arrived to make their floral arrangement contest at Arena Stage in Fichandler until Jan. 6. received information about the character who celebration of Eliza Doolittle, the Cockney decisions about the winners of the contest. The Each florist was paired with a signature cos- wore the costume and the production in which arrangements were on display throughout the flower girl in My Fair Lady, playing at the tume from a past Arena Stage production and it was featured. weekend. Big Gains in Amidon-Bowen Test Scores By Kara Kuchemba See related story, page 2 midon-Bowen Elementary School, under the supervision of Principal Iza- A bela Miller, has just recently completed in the Math PIA. -

2012 Information Guide

2012 INFORMATION GUIDE Mesa Peoria Phoenix Salt River Scottsdale Surprise Solar Sox Javelinas Desert Dogs Rafters Scorpions Saguaros BRYCE HARPER INTRODUCING THE UA SPINE HIGHLIGHT SUPER-HIGH. RIDICULOUSLY LIGHT. This season, Bryce Harper put everyone on notice while wearing the most innovative baseball cleats ever made. Stable, supportive, and shockingly light, they deliver the speed and power that will define the legends of this generation. Under Armour® has officially changed the game. Again. AVAILABLE 11.1.12 OFFICIAL PERFORMANCE Major League Baseball trademarks and copyrights are used with permission ® of Major League Baseball Properties, Inc. Visit MLB.com FOOTWEAR SUPPLIER OF MLB E_02_Ad_Arizona.indd 1 10/3/12 2:27 PM CONTENTS Inside Q & A .......................................2-5 Organizational Assignments ......3 Fall League Staff .........................5 Arizona Fall League Schedules ................................6-7 Through The Years Umpires .....................................7 Diamondbacks Saguaros Lists.......................................8-16 Chandler . 1992–94 Peoria.................2003–10 Desert Dogs Phoenix ...................1992 Top 100 Prospects ....................11 Mesa . .2003 Maryvale............1998–2002 Player Notebook ..................17-29 Phoenix ..... 1995–2002, ’04–11 Mesa . .1993–97 Mesa Solar Sox ....................31-48 Javelinas Surprise...................2011 Peoria Javelinas ...................49-66 Tucson . 1992–93 Scorpions Peoria...............1994–2011 Scottsdale . 1992–2004, ’06–11 -

Boston Red Sox World Series Champions

Page intentionally blank BOSTON RED SOX WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS BY MAXWELL HAMMER Published by The Child’s World® 1980 Lookout Drive • Mankato, MN 56003-1705 800-599-READ • www.childsworld.com ABOUT THE AUTHOR ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Maxwell Hammer The Child’s World®: Mary Berendes, Publishing Director Red Line Editorial: Editorial direction grew up in the The Design Lab: Design Adirondacks of New Amnet: Production Design elements: Open Clip Art Library York before becoming Photographs ©: Matt Slocum/AP Images, cover, 21; Charlie an international sports Riedel/AP Images, 5; Library of Congress, 7, 9; Bill Kostroun/ reporter and children’s AP Images, 11; Al Behrman/AP Images, 13; Winslow Townson/ AP Images, 15; Ben Margot/AP Images, 17; David J. Phillip/AP book author. When not Images, 19 traveling the world on Copyright © 2015 by The Child’s World® assignment, he spends All rights reserved. No part of this book may be his winters in Thunder reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. Bay, Ontario, with his wife and pet beagle. ISBN 9781631437359 LCCN 2014945444 Printed in the United States of America Mankato, MN November, 2014 PA02239 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 BOSTON STRONG ...........................................4 CHAPTER 2 ONE OF BASEBALL’S OLDEST TEAMS .............6 CHAPTER 3 THE CURSE .......................................................8 CHAPTER 4 SO CLOSE BUT SO FAR ..................................10 CHAPTER 5 A CITY CELEBRATES ........................................12 CHAPTER -

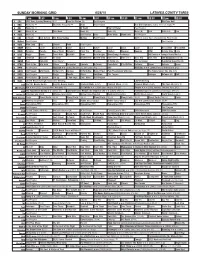

Sunday Morning Grid 6/28/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/28/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Red Bull Signature Series From Las Vegas. Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Vista L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Golf U.S. Senior Open Championship, Final Round. 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Bodyguard ›› (R) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Madison ›› (2001) Jim Caviezel, Jake Lloyd. -

1994 Topps Baseball Card Set Checklist

1994 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Mike Piazza 2 Bernie Williams 3 Kevin Rogers 4 Paul Carey 5 Ozzie Guillen 6 Derrick May 7 Jose Mesa 8 Todd Hundley 9 Chris Haney 10 John Olerud 11 Andujar Cedeno 12 John Smiley 13 Phil Plantier 14 Willie Banks 15 Jay Bell 16 Doug Henry 17 Lance Blankenship 18 Greg W. Harris 19 Scott Livingstone 20 Bryan Harvey 21 Wil Cordero 22 Roger Pavlik 23 Mark Lemke 24 Jeff Nelson 25 Todd Zeile 26 Billy Hatcher 27 Joe Magrane 28 Tony Longmire 29 Omar Daal 30 Kirt Manwaring 31 Melido Perez 32 Tim Hulett 33 Jeff Schwarz 34 Nolan Ryan 35 Jose Guzman 36 Felix Fermin 37 Jeff Innis 38 Brent Mayne 39 Huck Flener RC 40 Jeff Bagwell 41 Kevin Wickander 42 Ricky Gutierrez Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Pat Mahomes 44 Jeff King 45 Cal Eldred 46 Craig Paquette 47 Richie Lewis 48 Tony Phillips 49 Armando Reynoso 50 Moises Alou 51 Manuel Lee 52 Otis Nixon 53 Billy Ashley 54 Mark Whiten 55 Jeff Russell 56 Chad Curtis 57 Kevin Stocker 58 Mike Jackson 59 Matt Nokes 60 Chris Bosio 61 Damon Buford 62 Tim Belcher 63 Glenallen Hill 64 Bill Wertz 65 Eddie Murray 66 Tom Gordon 67 Alex Gonzalez 68 Eddie Taubensee 69 Jacob Brumfield 70 Andy Benes 71 Rich Becker 72 Steve Cooke 73 Bill Spiers 74 Scott Brosius 75 Alan Trammell 76 Luis Aquino 77 Jerald Clark 78 Mel Rojas 79 Billy Masse, Stanton Cameron, Tim Clark, Craig McClure 80 Jose Canseco 81 Greg McMichael 82 Brian Turang RC 83 Tom Urbani 84 Garret Anderson 85 Tony Pena 86 Ricky Jordan 87 Jim Gott 88 Pat Kelly 89 Bud Black Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 90 Robin Ventura 91 Rick Sutcliffe 92 Jose Bautista 93 Bob Ojeda 94 Phil Hiatt 95 Tim Pugh 96 Randy Knorr 97 Todd Jones 98 Ryan Thompson 99 Tim Mauser 100 Kirby Puckett 101 Mark Dewey 102 B.J. -

1986 Fleer Baseball Card Checklist

1986 Fleer Baseball Card Checklist 1 Steve Balboni 2 Joe Beckwith 3 Buddy Biancalana 4 Bud Black 5 George Brett 6 Onix Concepcion 7 Steve Farr 8 Mark Gubicza 9 Dane Iorg 10 Danny Jackson 11 Lynn Jones 12 Mike Jones 13 Charlie Leibrandt 14 Hal McRae 15 Omar Moreno 16 Darryl Motley 17 Jorge Orta 18 Dan Quisenberry 19 Bret Saberhagen 20 Pat Sheridan 21 Lonnie Smith 22 Jim Sundberg 23 John Wathan 24 Frank White 25 Willie Wilson 26 Joaquin Andujar 27 Steve Braun 28 Bill Campbell 29 Cesar Cedeno 30 Jack Clark 31 Vince Coleman 32 Danny Cox 33 Ken Dayley 34 Ivan DeJesus 35 Bob Forsch 36 Brian Harper 37 Tom Herr 38 Ricky Horton 39 Kurt Kepshire 40 Jeff Lahti 41 Tito Landrum 42 Willie McGee 43 Tom Nieto 44 Terry Pendleton Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 45 Darrell Porter 46 Ozzie Smith 47 John Tudor 48 Andy Van Slyke 49 Todd Worrell 50 Jim Acker 51 Doyle Alexander 52 Jesse Barfield 53 George Bell 54 Jeff Burroughs 55 Bill Caudill 56 Jim Clancy 57 Tony Fernandez 58 Tom Filer 59 Damaso Garcia 60 Tom Henke 61 Garth Iorg 62 Cliff Johnson 63 Jimmy Key 64 Dennis Lamp 65 Gary Lavelle 66 Buck Martinez 67 Lloyd Moseby 68 Rance Mulliniks 69 Al Oliver 70 Dave Stieb 71 Louis Thornton 72 Willie Upshaw 73 Ernie Whitt 74 Rick Aguilera 75 Wally Backman 76 Gary Carter 77 Ron Darling 78 Len Dykstra 79 Sid Fernandez 80 George Foster 81 Dwight Gooden 82 Tom Gorman 83 Danny Heep 84 Keith Hernandez 85 Howard Johnson 86 Ray Knight 87 Terry Leach 88 Ed Lynch 89 Roger McDowell 90 Jesse Orosco 91 Tom Paciorek Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 -

Local Teacher Dies in Tragic I-75 Pile-Up OMS Band Director Brian Gallaher One of 6 Victims by TONY EUBANK Crash That Occurred Near the Ooltewah As a Trumpet Player

FRIDAY 161st yEar • no. 49 jUnE 26, 2015 ClEVEland, Tn 22 PaGES • 50¢ Local teacher dies in tragic I-75 pile-up OMS band director Brian Gallaher one of 6 victims By TONY EUBANK crash that occurred near the Ooltewah as a trumpet player. While at Lee, he was together two or three days a week.” Banner Staff Writer Exit 11 marker. He leaves behind a wife School of Music Scholarship recipient Fisher said Gallaher brought life and a and two children. and a winner of the Performance Award. great energy to their running group. An Ocoee Middle School band teacher Not only had Gallaher served as the The much-beloved OMS band director “He was our default conversationalist,” was among the six motorists killed middle school’s longtime band director, was remembered early this morning by Fisher said. Thursday evening in a massive Interstate he was named Building Level Teacher of longtime friend Cameron Fisher, coordi- More importantly, Fisher added 75 wreck that investigators believe the Year twice. He attended Westmore nator of Communications at the Church Gallaher was an extremely talented involved as many as nine vehicles and 15 Church of God, where he served as the of God International Offices. teacher and trumpet player. people. church’s student orchestra director. “I’ve known Brian for about 15 years,” Chattanooga Police Department Brian Gallaher, a Lee University grad- Gallaher earned his bachelor’s degree Fisher told the Cleveland Daily Banner. spokesman Kyle Miller said the I-75 acci- uate who had served as OMS band direc- from Lee University in 2000, and went on “Even though he was a bit younger than tor for 14 years, died in the 7:10 p.m.