Understanding the Creative Economy in India's Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Officers Office of Director of Income Tax (Inv.) Chandigarh Sr

Directory of Officers Office of Director of Income Tax (Inv.) Chandigarh Sr. No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Address Contact Details (Sh./Smt./Ms/) 1 P.S. Puniha DIT (Inv.) Room No. - 201, 0172-2582408, Mob - 9463999320 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2587535 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 2 Adarsh Kumar ADIT (Inv.) (HQ) Room No. - 208, 0172-2560168, Mob - 9530765400 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2582226 Sector-2, Panchkula 3 C. Chandrakanta Addl. DIT (Inv.) Room No. - 203, 0172-2582301, Mob. - 9530704451 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2357536 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 4 Sunil Kumar Yadav DDIT (Inv.)-II Room No. - 207, 0172-2583434, Mob - 9530706786 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2583434 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 5 SurendraMeena DDIT (Inv.)-I Room No. 209, 0172-2582855, Mob - 9530703198 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2582855 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 6 Manveet Singh ADIT (Inv.)-III Room No. - 211, 0172-2585432 Sehgal Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2585432 Sector-2, Panchkula 7 Sunil Kumar Yadav DDIT (Inv.) Shimla Block No. 22, SDA 0177-2621567, Mob - 9530706786 Complex, Kusumpti, Fax-0177-2621567 Shimla-9 (H.P.) e-mail - [email protected] 8 Padi Tatung DDIT (Inv.) Ambala Aayakar Bhawan, 0171-2632839 AmbalaCantt Fax-0171-2632839 9 K.K. Mittal Addl. DIT (Inv.) New CGO Complex, B- 0129-24715981, Mob - 9818654402 Faridabad Block, NH-IV, NIT, 0129-2422252 Faridabad e-mail - [email protected] 10 Himanshu Roy ADIT (Inv.)-II New CGO Complex, B- 0129-2410530, Mob - 9468400458 Faridabad Block, NH-IV, NIT, Fax-0129-2422252 Faridabad e-mail - [email protected] 11 Dr.Vinod Sharma DDIT (Inv.)-I New CGO Complex, B- 0129-2413675, Mob - 9468300345 Faridabad Block, NH-IV, NIT, Faridabad e-mail - [email protected] 12 ShashiKajle DDIT (Inv.) Panipat SCO-44, Near Angel 0180-2631333, Mob - 9468300153 Mall, Sector-11, Fax-0180-2631333 Panipat e-mail - [email protected] 13 ShashiKajle (Addl. -

List of Blos 86-Faridabad NIT Assembly Constituency P.S

List of BLOs 86-Faridabad NIT Assembly Constituency P.S. No. Name of Polling Station Name of BLO Deg. Name of Dept. Surender 1 GPS Kot HT GPS Kot Singh Manju W/o GHSS 2 GMS, Manger AWW Manoj MANGAR 3 GMS, Manger Kavita AWW CDPO Old Rural 4 GPS Khori Jamalpur Maya AWW CDPO Rural 5 GPS Khori Jamalpur Santosh AWW CDPO Rural 6 GPS Serohi Pinki Rani AWW CDPO Rural 7 GPS Serohi Hari Singh JBT Guest GPS Serohi 8 GPS Alampur Naveen Kumar JBT GPS Alampur 9 GPS Alampur Geeta AWW CDPO Old Rural GPS, Gothara 10 GPS Gothra Mohobtabad Pankaj JBT Mohabatabad CDPO Rural old 11 GPS Gothra Mohobtabad Sunita AWW Fbd. 12 GPS Pakhal Ram Singh JBT GPS Pakhal GPS Kheri 13 GPS kheri Gujran Meenu Guest Teacher Gujran 14 GPS Pali Mithlesh AWW AWC Pali 15 GPS Pali Chandrawati AWW No706 CDPO OLD FBD 16 GSSS Pali (Boys) Rajesh Kumar JBT GSSS Gaunchi 17 GSSS Pali (Boys) Resh AWW 701 GHS(b) PALI 18 GSSS Pali (Boys) Sanyog AWW CDPO 19 GSSS Pali (Boys) Rajesh Kumar JBT GPS Pali 20 GHS Pawta Sangeeta AWW CDPO Pawta 21 GHS Pawta Mamta AWW CDPO Pawta Subhash 22 GHS Dhouj JBT GPS DHAUJ Chand Sushila W/o 23 GHS Dhouj AWW CDOP Rular Subhash 24 GHS Dhouj Mohd. Yunus JBT GPS Dhouj Ashiya W/o 25 GHS Dhouj AWW CDOP Rular Azad Sitara W/o 26 GHS Dhouj AWW CDOP Rular Sehjudeen 27 GHS Dhouj Dinesh Kumar JBT GPS Girls Dhouj Sarla W/o 28 GPS Girls Dhouj AWW CDPO Rular Bhagwan Dass ZulekhaW/o 29 GPS Girls Dhouj AWW CDOP Rular Mumtaj 30 GPS Tikri Khera Suresh kumar JBT GPS Tikri Khera 31 GPS Tikri Khera Najma AWW GPS Tikri Khera 32 GSSS Fatehpur Taga Anju Rani AWW 720 CDPO Old FBD List of BLOs 86-Faridabad NIT Assembly Constituency P.S. -

Faridabad…. a City of Industries

Faridabad…. a City of Industries A Factsheet Faridabad is located in northern India within the State of Haryana. It is about 284 km to the south of the state capital, Chandigarh, and is part of the National Capital Region, being about 32 km to the south of Delhi. It is the largest and most populous city in Haryana with a total population of 1,404,653. The town is bound on the north by State of Delhi, on the east by Agra and the Gurgaon canals and on the west by the Aravalli Hills. The River Yamuna flows on the northern side of the city and moves away as flows southward. Faridabad is the most industrialized city in the State of Haryana. It alone, generates about 60 percent of state revenues. There are about 15,000 small, medium and large industries in this area providing direct and indirect employment to nearly half a million people. It is ranked ninth amongst the largest industrial estates in Asia. City area 207.8 sq.km 35 wards AMRUT SMART SWACHH 14,04,653 63 slums CITY BHARAT (Census 2011) MISSION MISSION 1891 person 15.6% population FARIDABAD per sq.km. in slums Source of water supply to Faridabad city is ground water, tapped from 1,410 deep tube wells located in various parts of the city, and from seven rain-fed wells located along the River Yamuna; which flows, at a distance of about 10 km, along the length of Faridabad-Ballabgarh. Municipal Corporation Faridabad (MCF), has privatized operation and maintenance of all the tube wells supply water to the city. -

Ground Water Information Booklet of Alappuzha District

TECHNICAL REPORTS: SERIES ‘D’ CONSERVE WATER – SAVE LIFE भारत सरकार GOVERNMENT OF INDIA जल संसाधन मंत्रालय MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES कᴂ द्रीय भजू ल बो셍 ड CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD केरल क्षेत्र KERALA REGION भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका, मलꥍपुरम स्ज쥍ला, केरल रा煍य GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE तत셁वनंतपुरम Thiruvananthapuram December 2013 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA जी श्रीनाथ सहायक भूजल ववज्ञ G. Sreenath Asst Hydrogeologist KERALA REGION BHUJAL BHAVAN KEDARAM, KESAVADASAPURAM NH-IV, FARIDABAD THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 004 HARYANA- 121 001 TEL: 0471-2442175 TEL: 0129-12419075 FAX: 0471-2442191 FAX: 0129-2142524 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA TABLE OF CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2.0 CLIMATE AND RAINFALL ................................................................................... 3 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL TYPES .............................................................. 4 4.0 GROUNDWATER SCENARIO ............................................................................... 5 5.0 GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY .............................................. 11 6.0 GROUNDWATER RELATED ISaSUES AND PROBLEMS ............................... 14 7.0 AWARENESS AND TRAINING ACTIVITY ....................................................... 14 -

Delhi-IV(FARIDABAD) 294 PDF Created with Deskpdf PDF Writer - Trial :: DIVISION : II

CENTRAL EXCISE COMMISSIONERATE : DELHI-IV (FARIDABAD) 1 JURISDICTION : It is informed that there is no change in the jurisdiction of this Commissionerate as compared with the jurisdiction reported earlier in “Central Excise Formations At A Glance 2007-08” and, therefore, as advised, the same alongwith jurisdictional map of the Commissionerate is not being forwarded. 2(i) REVENUE REALISED DURING THE YEAR 2008-2009 AS COMPARED TO 2007-2008 YEAR TOTAL NO. OF UNITS REVENUE (Rs. in Crores) PLA CENVAT CREDIT 2007-08 2549 758.32 2758.04 2008-09 2727 340.33 2448.30 2(ii) DIVISION-WISE NET REVENUE REALIZED DURING THE YEAR 2008-09 AS COMPARED TO 2007-08 SL. NO. NAME OF DIVISIONS REVENUE (Rs. in Crores) PLA CENVAT CREDIT 2007-08 2008-09 2007-08 2008-09 1 Division-I 96.38 61.42 394.90 303.30 2 Division-II 333.97 139.24 988.66 872.10 3 Division-III 177.90 112.70 493.76 434.76 4 Division-IV 148.30 115.93 576.59 558.61 5 Division-V 97.34 62.51 304.97 279.53 TOTAL (Gross) Revenue 853.89 491.80 2758.88 2448.30 TOTAL Refund 95.57 151.47 0.84 0.00 TOTAL (Net) Revenue 758.32 340.33 2758.04 2448.30 2(iii) RANGE-WISE REVENUE REALIZED DURING THE YEAR 2008-09 AS COMPARED TO 2007-08 DIVISION : I SL. NO. NAME OF RANGES REVENUE (Rs. in Crores) PLA CENVAT CREDIT 2007-2008 2008-2009 2007-2008 2008-2009 1 I 13.41 12.24 36.07 22.41 2 II 41.00 24.91 173.09 145.73 3 III 11.19 6.17 20.58 33.13 4 IV 9.63 3.42 49.26 24.19 5 V 21.15 14.68 115.90 77.84 TOTAL (Gross) Revenue 96.38 61.42 394.90 303.30 TOTAL Refund 5.46 21.39 0.00 0.00 TOTAL (Net) Revenue 90.92 40.03 394.90 303.30 Delhi-IV(FARIDABAD) 294 PDF Created with deskPDF PDF Writer - Trial :: http://www.docudesk.com DIVISION : II SL. -

State: HARYANA Agriculture Contingency Plan District: FARIDABAD

State: HARYANA Agriculture Contingency Plan District: FARIDABAD 1.0 District Agriculture profile 1.1 Agro-Climatic/Ecological Zone Agro Ecological Sub Region (ICAR) Northern Plain (And Central Highlands) In (4.1) Agro -Climatic Region (Planning Commission) Trans Gangetic Plain Region (VI) Agro Climatic Zone (NARP)* Eastern Zone (HR -1) List all the districts falling under the NARP Zone Panchkula, Ambala, Yamunanagar, Kurukshetra, Karnal, Kaithal, Jind, Panipat, Sonipat, Faridabad, Mewat, Palwal and parts of Rohtak, Jhajjar and Gurgaon Geographical coordinates of district Latitude Longitude Altitude 28º22’55.99” N 77018’11.3” E 221 m Name and Address of the concerned ZRS/ZARS/RARS/RRTTS ZRS, Rohtak -124 001 Mention the KVK located in the district KVK, Faridabad- 121 002 1.2 Rainfall Average (mm) Normal Onset Normal Cessation (week and month) ( week and month) SW monsoon (June-Sep): 521.0 1st week of July 3rd week of September NE Monsoon(Oct -Dec): 20.2 - - Winter (Jan - March) 28.0 Summer (Apr-May) 26.4 Annual: 595.6 * If a district falls in two NARP zone, mention the zone in which more than 50% area falls. 1 1.3 Land use Total Forest Land under Permanent Cultivable Land under Misc. Barren and Current Other pattern of the geographical area non- pastures waste land tree crops and uncultivable fallows fallows district (latest area agricultural use groves land statistics) Area (000 ha) 172 1 40 2 - - 5 9 - (Source: Statistical Abstract Haryana: 2007-08) 1. 4 Major Soil types Area ('000 ha) Per cent (%) of total area Sandy loam soils 60 100 -

Commonfloor Insight on Bhiwadi Faridabad & Ghaziabad

COMMONFLOOR INSIGHT ON BHIWADI FARIDABAD & GHAZIABAD 1 | P a g e Introduction Delhi - NCR (National Capital Region) metropolitan region amounts for about 46,208 sq. km area accommodating over 45 million people and is ranked as India’s largest and world’s second largest urban agglomeration after New York city. The region attracts huge in-migration volume and thus, creates a pressure on the land supply which is handled by NCR Planning Board (constituted by the govt. of India by NCR Planning Board Act, 1985). This board tries to focus on the development radially outwards towards other districts in neighbouring states thus, expanding land area of the NCR belt altogether. The NCR belt is further divided into four sub-constituents: 1. Haryana Sub-Region 2. Uttar Pradesh Sub-Region 3. Rajasthan Sub-Region and 4. Delhi region with a stable government at Centre, consumer sentiments are getting positive and there is an increase in the real estate activity. Reports suggest that there was a surge of almost 50 per cent in Private Equity funds in 2014 as compared to 2013 in the realty market of Delhi-NCR. NCR is experiencing a consistent residential demand owing to exorbitant prices in the National Capital. The growth of NCR belt brings fresh development opportunities to these new sub-regions which contain huge untapped residential market potential. This report gives an overview of the three prominent markets in NCR namely Bhiwadi, Faridabad and Ghaziabad. BHIWADI (Rajasthan) Bhiwadi, in Alwar district of Rajasthan, is located in close proximity to Manesar and is an emerging industrial and real estate hub adjoining Gurgaon (49 km away). -

Publication Sale Notice SUB: OCC (IND SME SECURE) Limit of Rs

Publication Sale Notice Notice of intended sale under Rule 6(2) & 8(6) of The Security Interest (Enforcement Rules) 2002 under The Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act 2002 1. M/s Sai Hydro Pneumatic (Prop Ratipal Singh) Plot No 418 Nawada Bhakri Road, Nawada Village Faridabad 121002. 2. Mr. Ratipal Singh S/o Late. Hari Singh R/O H NO C-331 (D-1063 A) Dabua Colony, Mauza Dabua NIT Faridabad Haryana 121002. 3. Late. Hari Singh S/o Late. Umrao Singh R/O H NO C-331 (D-1063 A) Dabua Colony, Mauza Dabua NIT Faridabad Haryana 121002 (Through Legal Heirs & Successors in heritance). a) Mrs. Vidya Devi w/o Late Hari Singh R/O H NO C-331 (D-1063 A) Dabua Colony, Mauza Dabua NIT Faridabad Haryana 121002. b) Mr. Ratipal Singh S/o Late. Hari Singh R/O H NO C-331 (D-1063 A) Dabua Colony, Mauza Dabua NIT Faridabad Haryana 121002. c) Mrs. Laxmi D/o Late Hari Singh R/O H NO C-331 (D-1063 A) Dabua Colony, Mauza Dabua NIT Faridabad Haryana 121002. d) Mrs. Sanju D/o Late Hari Singh R/O H NO C-331 (D-1063 A) Dabua Colony, Mauza Dabua NIT Faridabad Haryana 121002. SUB: OCC (IND SME SECURE) Limit of Rs 32.00 Lacs Loan A/c No. 6302268157 in the name of M/s Sai Hydro Pneumatic with Indian Bank, Sector 37 Faridabad Branch. M/s Sai Hydro Pneumatic (Prop Mr. Ratipal Singh) and Late. Hari Singh has availed OCC/ IND MSME Secure facility from Indian Bank, Sector 37 Faridabad branch, and the repayment of which are secured by mortgage of schedule mentioned properties hereinafter referred to as “the Properties”. -

Hindi & English

CultureTalk India Video Transcripts: http://langmedia.fivecolleges.edu Suburbs of Delhi Hindi transcript: िदली इंिडया का capital है, राजधानी है, और िदली मQ तकरीबन एक करोड़ से यादा लोग रहते हQ। काफ़ी भीड़ -भाड़ है, और रहने की जगह ढँढनाू बड़ा मिँकल है िदली मQ। और इतनी भीड़ मQ, इतने लोगU मQ, आपको कोई जगह िमल भी जाए तो या तो आपको location पसंद नहीं आएगी या िफ र आपको इतना expensive लगेगा िक आप उसको खरीद नहीं सकते या even rent पे भी ले नहीं सकते। तो िदली मQ बहतु सारे suburbs उभर कर आ रहे हS िपछले आठ -दस सालU से जैसे िक नॉयडा , ग़ािज़याबाद और फ़रीदाबाद , कुछ हद तक सोनीपत और पानीपत भी। पर ग़ािज़या , नॉयडा और फ़रीदाबाद िदली के main suburbs हS जहाँ पे बहतु यादा development हो रहा है। इन तीनU मQ से नॉयडा सबसे एयादा ... िदली के पास है, एकदम िदली से जुडा़ हआु है, एक highway से जुडा़ हआु है िदली से और वो highway... जमुना को .. के .. ऊपर है। और नॉयडा बहतु एयादा grow कर रहा है आजकल। नॉयडा मQ IT sector established है और बहतु एयादा नए -नए लोग , वहां पे specially जो IT field मQ काम करते हS, नॉयडा मQ रहते हS। नॉयडा planned city है, वहां पे.. -

List of Empanelled Hospitals

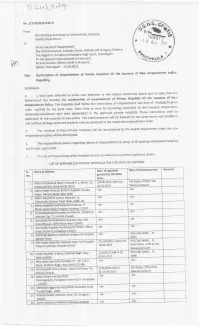

a "[^: a , f \^ ' C- ft]^Y' t",l] Na. 21 27 6 | 2012-l H B-lll From Government, Haryana' /ff"u The Principal Secretary to Health DePartment. To t.,oW All the Heads of Departments \ Hissar, Rohtak and Gurgaon Division' R The Commissioners, Ambala, \^ The Registrar, Punjab and Haryana High Court' Chandigarh' \rl(qrr,xu All the Deputy Commissioners in Haryana ,r-y All Sub-Division Officer (Civil) in Haryana Dated Chandigarh 13'08.2015 the issuance of llew Empanelment policy- Sub:- Continuation of Empanelment of Private Hospitals till Regarding. Sir/Madam mentioned above and to state that the 2. l, have been directed to invite your attention to the subject Private Hospitalsi till the issuance of New Governmerlt has decided the continuation of ernpanelment of empanelment and that of Package/lmplant Ernpanelment Policy. The hospitals shall follow the instructions of treatment to the Haryana Government rates notified by the state Govt. from time to time for providing private hospitals' 'fhese instructions shall be employees/pensioners and their dependents in the approved be allowed on the same terms and conditions applicable till the issuance of new policy. The reimbursement will empanelment order' and notified package rates and implants rates as explained in the respective the Health Departrnent when the new 3. The renewal of these private Hospitals will be reconsidered by empanelment policy will be introduced' (2 years) of all existing empanelled hospitals 4. The empanelment orders regarding period of empanelment are hereby suPerseded. to continue is given as under:- 5. The list of Private Empanelled Hospitals which are aliowed L|sToFEMPANELLEDPR|VATEHOSP|TALSFoRTHESTATEoFHARYANA Remarks Date of aPProval Rate of reimbursement Sr. -

Consolidated List Private Universities

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-wise List of Private Universities as on 06.08.2021 S.No Name of Private University Date of Notification ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1. Apex Professional University, Pasighat, District East Siang, 10.05.2013 Arunachal Pradesh - 791102. 2. Arunachal University of Studies, NH-52, Namsai, Distt – Namsai 26.05.2012 - 792103, Arunachal Pradesh. 3. Arunodaya University, E-Sector, Nirjuli, Itanagar, Distt. Papum 21.10.2014 Pare, Arunachal Pradesh-791109 4. Himalayan University, 401, Takar Complex, Naharlagun, 03.05.2013 Itanagar, Distt – Papumpare – 791110, Arunachal Pradesh. 5. North East Frontier Technical University, Sibu-Puyi, Aalo 03.09.2014 (PO), West Siang (Distt.), Arunachal Pradesh –791001. 6. The Global University, Hollongi, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 18.09.2017 7. The Indira Gandhi Technological & Medical Sciences University, 26.05.2012 Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. 8. Venkateshwara Open University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 20.06.2012 Andhra Pradesh 9. Bharatiya Engineering Science and Technology Innovation 17.02.2019 University, Gownivaripalli, Gorantla Mandal, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh 10. Centurian University of Technology and Management, Gidijala 23.05.2017 Junction, Anandpuram Mandal, Visakhapatnam- 531173, Andhra Pradesh. 11. KREA University, 5655, Central, Expressway, Sri City-517646, 30.04.2018 Andhra Pradesh 12. Saveetha Amaravati University, 3rd Floor, Vaishnavi Complex, 30.04.2018 Opposite Executive Club, Vijayawada- 520008, Andhra Pradesh 13. SRM University, Neerukonda-Kuragallu Village, mangalagiri 23.05.2017 Mandal, Guntur, Dist- 522502, Andhra Pradesh (Private University) 14. VIT-AP University, Amaravati- 522237, Andhra Pradesh (Private 23.05.2017 University) ASSAM 15. Assam Don Bosco University, Azara, Guwahati 12.02.2009 16. Assam Down Town University, Sankar Madhab Path, Gandhi 29.04.2010 Nagar, Panikhaiti, Guwahati – 781 036. -

Urban Agglomerations 2014 Wall Chart

United Nations • Department of Economic and Social Affairs • Population Division • www.unpopulation.org Urban Agglomerations 2014 Average annual 2014 population residing Average annual 2014 population residing Average annual 2014 population residing Population rate of change in agglomeration, Population rate of change in agglomeration, Population rate of change in agglomeration, (millions) Rank* (percentage) as percentage of (millions) Rank* (percentage) as percentage of (millions) Rank* (percentage) as percentage of Total Urban Total Urban Total Urban Urban agglomeration Country 1990 2014 2030 1990 2014 2030 2010–2015 2025–2030 population population Urban agglomeration Country 1990 2014 2030 1990 2014 2030 2010–2015 2025–2030 population population Urban agglomeration Country 1990 2014 2030 1990 2014 2030 2010–2015 2025–2030 population population A Hims (Homs)66 Syrian Arab Republic 0.6 1.6 2.5 404 291 245 4.0 2.1 7.3 12.7 Port-au-Prince109 Haiti 1.1 2.4 3.5 213 185 165 2.6 1.9 22.7 39.5 Abidjan Côte d'Ivoire 2.1 4.7 7.8 106 77 62 3.2 2.9 22.6 42.3 Hiroshima Japan 2.0 2.2 2.2 120 207 280 0.5 -0.1 1.7 1.8 Portland United States of America 1.2 2.0 2.3 204 229 261 1.5 0.9 0.6 0.8 Abu Zaby (Abu Dhabi) United Arab Emirates 0.3 1.1 1.6 459 424 385 5.3 1.8 11.8 13.8 Hohhot67 China 0.6 1.7 2.4 381 269 252 3.8 1.2 0.1 0.2 Porto110 Portugal 1.2 1.3 1.4 209 358 426 0.2 0.7 12.2 19.4 Abuja1 Nigeria 0.3 2.3 4.9 460 191 108 5.9 3.9 1.3 2.7 Hong Kong68 China, Hong Kong SAR 5.8 7.3 7.9 29 44 61 0.7 0.4 100.0 100.0 Pôrto Alegre Brazil 2.7 3.6 4.0 77 107