Development in Southern California After World War II: Architecture, Photography, & Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Esther Mccoy Research Papers, Circa 1940-1989 0000103

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8d21wm4 No online items Finding Aid for the Esther McCoy research papers, circa 1940-1989 0000103 Finding aid prepared by Jillian O'Connor,Chris Marino and Jocelyne Lopez The processing of this collection was made possible through generous funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, administered through the Council on Library and Information Resources “Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives” Project. Architecture and Design Collection, Art, Design & Architecture Museum Arts Building Room 1434 University of California Santa Barbara, California, 93106-7130 805-893-2724 [email protected] Finding Aid for the Esther McCoy 0000103 1 research papers, circa 1940-1989 0000103 Title: Esther McCoy research papers Identifier/Call Number: 0000103 Contributing Institution: Architecture and Design Collection, Art, Design & Architecture Museum Language of Material: English Physical Description: 4.0 Linear feet(2 boxes, 1 oversize box and 1 flat file drawer) Date (inclusive): circa 1940-circa 1984 Location note: Boxes 1-2/ADC - regular Box 3/ADC - oversize** 1 Flat File Drawer/ADC - flat files creator: Abell, Thornton M., (Thornton Montaigne), 1906-1984 creator: Bernardi, Theodore C., 1903- creator: Davidson, Julius Ralph, 1889-1977 creator: Killingsworth, Brady, Smith and Associates. creator: McCoy, Esther, 1920-1989 creator: Neutra, Richard Joseph, 1892-1970 creator: Rapson, Ralph, 1914-2008 creator: Rex, John L. creator: Schindler, R. M., (Rudolph M. ), 1887-1953 creator: Smith, Whitney Rowland, 1911-2002 creator: Soriano, Raphael, 1904-1988 creator: Spaulding, Sumner, 1892/3-1952 creator: Walker, Rodney creator: Wurster, William Wilson Access Open for use by qualified researchers. Custodial History note Gift of Esther McCoy, 1984. -

The Archive of Renowned Architectural Photographer

DATE: August 18, 2005 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE GETTY ACQUIRES ARCHIVE OF JULIUS SHULMAN, WHOSE ICONIC PHOTOGRAPHS HELPED TO DEFINE MODERN ARCHITECTURE Acquisition makes the Getty one of the foremost centers for the study of 20th-century architecture through photography LOS ANGELES—The Getty has acquired the archive of internationally renowned architectural photographer Julius Shulman, whose iconic images have helped to define the modern architecture movement in Southern California. The vast archive, which was held by Shulman, has been transferred to the special collections of the Research Library at the Getty Research Institute making the Getty one of the most important centers for the study of 20th-century architecture through the medium of photography. The Julius Shulman archive contains over 260,000 color and black-and-white negatives, prints, and transparencies that date back to the mid-1930s when Shulman began his distinguished career that spanned more than six decades. It includes photographs of celebrated monuments by modern architecture’s top practitioners, such as Richard Neutra, Frank Lloyd Wright, Raphael Soriano, Rudolph Schindler, Charles and Ray Eames, Gregory Ain, John Lautner, A. Quincy Jones, Mies van der Rohe, and Oscar Niemeyer, as well as images of gas stations, shopping malls, storefronts, and apartment buildings. Shulman’s body of work provides a seminal document of the architectural and urban history of Southern California, as well as modernism throughout the United States and internationally. The Getty is planning an exhibition of Shulman’s work to coincide with the photographer’s 95th birthday, which he will celebrate on October 10, 2005. The Shulman photography archive will greatly enhance the Getty Research Institute’s holdings of architecture-related works in its Research Library, which -more- Page 2 contains one of the world’s largest collections devoted to art and architecture. -

339623 1 En Bookbackmatter 401..420

References Alexander, Christopher, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein. 1977. A pattern language: Towns, buildings, construction. New York: Oxford University Press. Allen, Gary L. 2004. Human spatial memory: Remembering where. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. Amidon, E.L. and G.H. Elsner. 1968. Delineating landscape view areas: A computer approach. In Forest Research Note PSW–180, ed. US Department of Agriculture. Washington DC. Amini Behbahani, Peiman, Michael J. Ostwald, and Ning Gu. 2016. A syntactical comparative analysis of the spatial properties of Prairie style and Victorian domestic architecture. The Journal of Architecture 21 (3): 348–374. Amini Behbahani, Peiman, Ning Gu, and Michael J. Ostwald. 2017. Viraph: Exploring the potentials of visibility graphs and their analysis. Visualization in Engineering 5 (17). https:// doi.org/10.1186/s40327-017-0056-z. Amorim, Luiz. 1999. The sectors paradigm: A study of the spatial and functional nature of modernist housing in northeast Brazil. London: University of London. Antonakaki, Theodora. 2007. Lighting and spatial structure in religious architecture: A comparative study of a Byzantine church and an early Ottoman mosque in the city of Thessaloniki. In Proceedings 6th International Space Syntax Symposium, 057.02–057.14. Istanbul. Appleton, Jay. 1975. The experience of landscape. London: John Wiley and Sons. Asami, Yasushi, Ayse Sema Kubat, Kensuke Kitagawa, and Shin-ichi Iida. 2003. Introducing the third dimension on Space Syntax: Application on the historical Istanbul. In Proceedings 4th International Space Syntax Symposium, 48.1–48.18. London. Aspinall, Peter. 1993. Aspects of spatial experience and structure. In Companion to contemporary architectural thought, ed. Ben Farmer, and Hentie Louw, 334–341. -

Collaborations: the Private Life of Modern Architecture Author(S): Beatriz Colomina Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol

Collaborations: The Private Life of Modern Architecture Author(s): Beatriz Colomina Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 58, No. 3, Architectural History 1999/2000 (Sep., 1999), pp. 462-471 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/991540 Accessed: 25-09-2016 19:05 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians This content downloaded from 204.168.144.216 on Sun, 25 Sep 2016 19:05:51 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Collaborations The Private Life of Modern Architecture BEATRIZ COLOMINA Princeton University bout a year ago, I gave a lecture form in the Madrid, space-and how the there city is nothing in Mies's work, where I was born. The lecture was on the work of prior to his collaboration with Reich, that would suggest Charles and Ray Eames and, to my surprise, most such a radical approach to defining space by suspended sen- of the discussion at the dinner afterward centered around suous surfaces, which would become his trademark, as the role of Ray, her background as a painter, her studies with exemplified in his Barcelona Pavilion of 1929. -

Topics in Modern Architecture in Southern California

TOPICS IN MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ARCH 404: 3 units, Spring 2019 Watt 212: Tuesdays 3 to 5:50 Instructor: Ken Breisch: [email protected] Office Hours: Watt 326, Tuesdays: 1:30-2:30; or to be arranged There are few regions in the world where it is more exciting to explore the scope of twentieth-century architecture than in Southern California. It is here that European and Asian influences combined with the local environment, culture, politics and vernacular traditions to create an entirely new vocabulary of regional architecture and urban form. Lecture topics range from the stylistic influences of the Arts and Crafts Movement and European Modernism to the impact on architecture and planning of the automobile, World War II, or the USC School of Architecture during the 1950s. REQUIRED READING: Thomas S., Hines, Architecture of the Sun: Los Angeles Modernism, 1900-1970, Rizzoli: New York, 2010. You can buy this on-line at a considerable discount. Readings in Blackboard and online. Weekly reading assignments are listed in the lecture schedule in this syllabus. These readings should be completed before the lecture under which they are listed. RECOMMENDED OPTIONAL READING: Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, 1971, reprint ed., Berkeley; University of California Press, 2001. Barbara Goldstein, ed., Arts and Architecture: The Entenza Years, with an essay by Esther McCoy, 1990, reprint ed., Santa Monica, Hennessey and Ingalls, 1998. Esther McCoy, Five California Architects, 1960, reprint ed., New York: -

NEWS from the GETTY DATE: June 10, 2009 for IMMEDIATE RELASE

The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 400 Tel 310 440 7360 Communications Department Los Angeles, California 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 www.getty.edu [email protected] NEWS FROM THE GETTY DATE: June 10, 2009 FOR IMMEDIATE RELASE GETTY PARTICIPATES IN 2009 GUADALAJARA BOOK FAIR Getty Research Institute and Getty Publications to help represent Los Angeles in the world’s largest Spanish-language literary event Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles At the Museo de las Artes, Guadalajara, Mexico November 27, 2009–January 31, 2010 LOS ANGELES—The Getty today announced its participation in the 2009 International Book Fair in Guadalajara (Feria Internacional del Libro de Guadalajara or FIL), the world’s largest Spanish-language literary event. This year, the city of Los Angeles has been invited as the fair’s guest of honor – the first municipality to be chosen for this recognition, which is usually bestowed on a country or a region. Both Getty Publications and the Getty Research Institute (GRI) will participate in the fair for the first time. Getty Publications will showcase many recent publications, including a wide selection of Spanish-language titles, and the Getty Research Institute will present the extraordinary exhibition, Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles, which includes 110 rarely seen photographs from the GRI’s Julius Shulman photography archive, which was acquired by the Getty Research Institute in 2005 and contains over 260,000 color and black-and-white negatives, prints, and transparencies. “We are proud to help tell Los Angeles’ story with this powerful exhibition of iconic and also surprising images of the city’s growth,” said Wim de Wit, the GRI’s senior curator of architecture and design. -

The Kaufmann House, a Seminal Modernist Masterpiece, to Be Offered for Sale at Christie’S

For Immediate Release October 31, 2007 Contact: Rik Pike 212.636.2680 [email protected] THE KAUFMANN HOUSE, A SEMINAL MODERNIST MASTERPIECE, TO BE OFFERED FOR SALE AT CHRISTIE’S © J. Paul Getty Trust. Used with permission The Kaufmann House May 13, 2008 New York - Christie’s Realty International, Inc. is delighted to announce the sale of Richard Neutra’s seminal Kaufmann House on the night of Christie’s New York May 13 Spring 2008 Post- War and Contemporary Art Evening sale. Along with Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House and Philip Johnson’s Glass House, Neutra’s Kaufmann House is one the most important examples of modernist residential architecture in the Americas and remains singular as the most important example of mid-century modernist architecture in the Americas to remain in private hands. It carries an estimate of $15,000,000 to $25,000,000. Christie’s Realty International Inc. 20 Rockefeller Plaza, New York, NY 10020 phone 212.478.7118 www.christies.com In 1946, the Pittsburgh department store magnate, Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr., who had previously commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to build Fallingwater, engaged Richard Neutra to build a house in the Palm Springs desert as a winter retreat for his wife and him. Representing the purest realization of Neutra's modernist ideals, the Kaufmann House's rigorously disciplined design scheme integrates horizontal planes of cantilevered roofs under which blocks of glass floor-to-ceiling sliding walls shimmer. Set against the rugged backdrop of a mountainous landscape in the Palm Springs desert and positioned in an equally minimalist paradise of manicured lawns, placed boulders and plantings, this modernist icon represents the culmination of Neutra's highly influential achievement and contribution to architectural history. -

The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W

The Journal of San Diego History SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Winter 1990, Volume 36, Number 1 Thomas L. Scharf, Editor The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W. Amero Researcher and Writer on the history of Balboa Park Images from this article On July 9, 1901, G. Aubrey Davidson, founder of the Southern Trust and Commerce Bank and Commerce Bank and president of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, said San Diego should stage an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal. He told his fellow Chamber of Commerce members that San Diego would be the first American port of call north of the Panama Canal on the Pacific Coast. An exposition would call attention to the city and bolster an economy still shaky from the Wall Street panic of 1907. The Chamber of Commerce authorized Davidson to appoint a committee to look into his idea.1 Because the idea began with him, Davidson is called "the father of the exposition."2 On September 3, 1909, a special Chamber of Commerce committee formed the Panama- California Exposition Company and sent articles of incorporation to the Secretary of State in Sacramento.3 In 1910 San Diego had a population of 39,578, San Diego County 61,665, Los Angeles 319,198 and San Francisco 416,912. San Diego's meager population, the smallest of any city ever to attempt holding an international exposition, testifies to the city's extraordinary pluck and vitality.4 The Board of Directors of the Panama-California Exposition Company, on September 10, 1909, elected Ulysses S. -

News from the Getty

The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 400 Tel 310 440 7360 Communications Department Los Angeles, California 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 www.getty.edu [email protected] NEWS FROM THE GETTY DATE: February 9, 2010 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE GETTY PARTICIPATES IN 2010 ARCOmadrid Getty Research Institute to help represent Los Angeles at International Contemporary Art Fair Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles At the Canal de Isabel II, Madrid, Spain February 16–May 16, 2010 Shulman, Julius. Simon Rodia's Towers (Los Angeles, Calif.), 1967. Gelatin silver. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Used with permission. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute (2004.R.10) LOS ANGELES—The Getty Research Institute today announced its participation in the 2010 ARCOmadrid, an international contemporary arts fair. For the first time in the Fair’s 29-year history, ARCOmadrid is honoring a city, rather than a country, in a special exhibition titled Panorama: Los Angeles, recognizing L.A. as one of the most prolific and vibrant contemporary arts centers in the international art world. As part of ARCOmadrid’s exciting roster of satellite exhibitions, the Getty Research Institute (GRI) will showcase the extraordinary exhibition Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles, in collaboration with Comunidad de Madrid, which includes over 100 rarely seen photographs from the GRI’s Julius Shulman photography archive, which was acquired in 2005 and contains over 260,000 color and black-and-white negatives, prints, and transparencies. “We are delighted that the Getty Research Institute is bringing Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles to ARCOMadrid. -

Dialogues with Design U.S

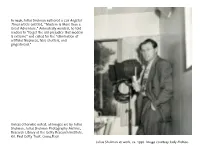

SAH/SCC ;m.iT/y4f i^n..i rA^rt r IN s © AS VFNI.n TAS office 9 2 2 2 4 1 10 9 - 2 2 2 4 8 0 0 dialogues with design U.S. Postage FIRST CLASS MAIL PAID eservathn alert page 2 Pasadena, CA Permit No. 740 anish romance tour page 3 January and february events pages 4-5 architectural exhibitions page 6 historic theaters colloquium page 7 Julius Shulman and Richard Neutra in 7950, DIALOGUES WITH DESIGN ESTHER MCCOY LECTURE SERIES: JANUARY 25TH SAH/SCC News editor Julie D. Taylor, will Sunday, January 25th, will be the first installment continue throughout the year, and be held at the of the re-instituted Esther McCoy Lecture Series. LA Central Library downtown, from 1PM to 3PM. Every two months, "Dialogues With Design" will The Sunday afternoon programs are free and present two individuals who will engage in open to the public, but SAH/SCC members are conversation about the architectural history of Los given preferential seating. Reservations are Angeles. The first session focuses on photography necessary, and can be made by filling out the with Julius Shulman, chronicler of the legendary form on Page 8, or calling 800.9SAHSCC. LA modern architects, and Tom Bonner, who Julius Shulman was born in 1910 in documents LA's cutting-edge architecture. Work Brooklyn, and moved to California when he was by both photographers can be seen in the new 10 years old. He took a basic photography course publication The J. Paul Getty Museum and Its at Roosevelt High School when he was 16, which Collections, with Shulman's images of the Getty was his only formal training. -

All the Arts, All the Time

5/6/2015 PST, A to Z: ‘Eames’ at A+D Museum, ‘Sympathetic’ at MAK Center | Culture Monster | Los Angeles Times ALL THE ARTS, ALL THE TIME « Previous Post | Culture Monster Home | Next Post » OCTOBER 11, 2011 | 2:00 PM Pacific Standard Time will explore the origins of the Los Angeles art world through museum exhibitions throughout Southern California over the next six months. Times art reviewer Sharon Mizota has set the goal of seeing all of them. This is her latest report. Text is a central component of two Pacific Standard Time exhibitions, both focused on design: “Eames Designs: The Guest Host Relationship” at the A+D Museum, and “Sympathetic Seeing: Esther McCoy and the Heart of American Modernist Architecture and Design” at the MAK Center. The former whimsically uses everyday objects to illustrate quotes from midcentury designers Charles and Ray Eames; the latter is an engaging exploration of the life and work of McCoy, a writer and historian who, during her 40-plus-years career, championed and pretty much defined modern architecture in California. The linchpin of each show is the way in which text interacts with the data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Cdiv%20id%3D%22blog-header%22%20style%3D%22border-bottom-width%3A%201px%3B%20border-bottom-style%3A%20soli… 1/6 5/6/2015 PST, A to Z: ‘Eames’ at A+D Museum, ‘Sympathetic’ at MAK Center | Culture Monster | Los Angeles Times objects or spaces on view, providing fresh perspectives on icons of Southern California design and architecture. Throughout the A+D Museum, curators Deborah Sussman and Andrew Byrom have splashed the walls with quotes from husband and wife designers Charles and Ray Eames. -

Julius Shulman

In 1946, Julius Shulman authored a Los Angeles Times article entitled, "Modern is More than a Great Adventure.” Animatedly worded, he told readers to "forget the old prejudice that modern is extreme" and called for the "elimination of artificial fireplaces, false shutters, and gingerbread." Unless otherwise noted, all images are by Julius Shulman. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute. ©J. Paul Getty Trust. (2004.R.10) Julius Shulman at work, ca. 1950. Image courtesy Judy McKee. As we reflect on his adventure promoting architecture and design, we realize there are even more stories to be told through his extensive archive. Julius Shulman photographing Case Study House #22, Pierre Koenig, photographed in 1960. Now housed at the Getty Research Institute, we find iconic images of modern living . Case Study House #22, Pierre Koenig, photographed in 1960. as well as some images of . gingerbread. Outtake of a Christmas cookie assignment for Sunset magazine, 1948. More than a great adventure, the Julius Shulman Photography Archive illustrates the lifelong career of Julius Shulman . Julius Shulman on assignment in Israel, 1959. in California . Downtown Los Angeles at night showing Union Bank Plaza, photographed in 1968. across the United States . Marina City, Bertrand Goldberg, Chicago, Illinois, photographed in 1963. and abroad. View of Ministry of Justice and Government Building from Senate Building, Oscar Niemeyer, Brasìlia, Brazil, photographed in 1977. Interspersed throughout the archive are handwritten thoughts . essays . occasional celebrity sightings . Actress Jayne Mansfield demonstrates an in-counter blender for NuTone Inc., 1959. and photographic evidence of his spirited sense of humor! The last shot of 153 images taken at Bullock’s Pasadena, Wurdeman and Becket, 1947.