Some Old Roads of North Berkshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ttu Mac001 000057.Pdf (19.52Mb)

(Vlatthew flrnold. From the pn/ture in tlic Oriel Coll. Coniinon liooni, O.vford. Jhc Oxford poems 0[ attfiew ("Jk SAoUi: S'ips\i' ani "Jli\j«'vs.'') Illustrated, t© which are added w ith the storv of Ruskin's Roa(d makers. with Glides t© the Country the p©em5 iljystrate. Portrait, Ordnance Map, and 76 Photographs. by HENRY W. TAUNT, F.R.G.S. Photographer to the Oxford Architectural anid Historical Society. and Author of the well-knoi^rn Guides to the Thames. &c., 8cc. OXFORD: Henry W, Taunl ^ Co ALI. RIGHTS REStHVED. xji^i. TAONT & CO. ART PRINTERS. OXFORD The best of thanks is ren(iered by the Author to his many kind friends, -who by their information and assistance, have materially contributed to the successful completion of this little ^rork. To Mr. James Parker, -who has translated Edwi's Charter and besides has added notes of the greatest value, to Mr. Herbert Hurst for his details and additions and placing his collections in our hands; to Messrs Macmillan for the very courteous manner in which they smoothed the way for the use of Arnold's poems; to the Provost of Oriel Coll, for Arnold's portrait; to Mr. Madan of the Bodleian, for suggestions and notes, to the owners and occupiers of the various lands over which •we traversed to obtain some of the scenes; to the Vicar of New Hinksey for details, and to all who have helped with kindly advice, our best and many thanks are given. It is a pleasure when a ^ivork of this kind is being compiled to find so many kind friends ready to help. -

Wootton Abingdon Parish Council

Wootton (Abingdon) 415 Number Status Description Width Conditions + Limitations Remarks (non-conclusive information) 1 FP From Old Boars Hill Road opposite property "Linnens Field", ESE to FP 3, on Wootton Heath. 2 FP From commencement of FP 1, SE and E to FP 3, NW of "The Fox" Inn. 3 FP From "Norman Bank", Old Boars Hill Road, SE to Fox Lane near "The Fox" Inn. 4 FP From Fox Lane near drive to Blagrove Farm, ESE to Diversion Order confirmed Diversion Order confirmed 25.3.1975. Sunningwell Parish boundary. 25.3.75 provided 5 feet width over diverted 5 FP From The Ridgeway opposite Masefield House, WSW across FP 18 to Sandy Lane opposite Wootton Close Cottages. 6 FP From Cumnor Road adjoining property "High Winds" (No.166) near Middleway Farm, ENE to Wootton Village Road opposite School. 7 BR From The Community Centre at junction of Besselsleigh Road and Cumnor Road, SW to St. Helen Without Parish boundary at NE end of Landsdown Road. 8 FP From FP 6, W of Wootton School, WNW across Cumnor Road (B4017) to the Besselsleigh Parish boundary at its junction with Besselsleigh FP 7, SE of Little Bradley 9 FP From Old Boars Hill, opposite "Norman Bank", W and SW to Old Boars Hill Road at Mankers Hill. 10 BR From Old Boars Hill at entrance to Jarn Mound, NNE to Ridgeway opposite West Gardens Drive and property "Pleasant Lane". 11 FP From Road opposite Wootton Village Green, SE and S crossing FP 9 to Old Boars Hill Road and Fox Lane NW of Blagrove Farm. -

Appleton with Eaton Community Plan

Appleton with Eaton Community Plan Final Report & Action Plan July 2010 APPLETON WITH EATON COMMUNITY PLAN PART 1: The Context Section A: The parish of Appleton with Eaton is situated five miles south west of Oxford. It Appleton with Eaton consists of the village of Appleton and the hamlet of Eaton, together totalling some 900 inhabitants. It is surrounded by farmland and woods, and bordered by the Thames to the north-west. Part of the parish is in the Oxford Green Belt, and the centre of Appleton is a conservation area. It is administered by Oxfordshire County Council, The Vale of the White Horse District Council and Appleton with Eaton Parish Council. Appleton and Eaton have long histories. Appleton is known to have been occupied by the Danes in 871 AD, and both settlements are mentioned in the Doomsday Book. Eaton celebrated its millennium in 1968. The parish’s buildings bear witness to its long history, with the Manor House and St Laurence Church dating back to the twelfth century, and many houses which are centuries old. Appleton’s facilities include a community shop and part-time post office, a church, a chapel, a village hall, a primary school, a pre-school, a pub, a sportsfield and a tennis club. Eaton has a pub. There is a limited bus service linking the parish with Oxford, Swindon, Southmoor and Abingdon. There are some twenty-five clubs and societies in Appleton, and a strong sense of community. Businesses in the parish include three large farms, a long-established bell-hanging firm, a saddlery, an electrical systems firm and an increasing number of small businesses run from home. -

Speech Made by Mervyn Hughes on the Unveiling of the Oxfordshire Blue Plaque at Wytham Woods on 7 October 2017

The ffennell family and Wytham Woods Speech made by Mervyn Hughes on the unveiling of the Oxfordshire blue plaque at Wytham Woods on 7 October 2017 The Schumacher family had lived in the Brunswick part of Germany since at least the fifteenth century and always had important roles in the running of the area. August Schumacher was a Privy Councillor and worked for Frederick, Duke of Brunswick who was killed in the last battle before Waterloo. August fought for the Prussians at Waterloo in 1815. He belonged to the “Black Brunswickers”. August later married Fanny Marc in about 1823. One of their children was Erwin. His older sister married into the Wagau family which enabled Erwin to join the company, soon becoming a partner. The Wagau family had traded in Russia since 1839. Erwin moved to London and opened a Wagau office, then in 1903 he swore an “Oath of Allegiance” to the Crown. The company traded in “colonial and chemical” commodities, including Chinese tea, American cotton, West Indian sugar, and English wool. Every town or city had a Wagau agent, part of a huge network. At the outbreak of WW1 the company (in today’s money) was worth about 3 billion pounds. All of Erwin’s six children were born in London: Erwin (Junior), Raymond, Gladys, Walter, Vera, and Elsa. Raymond attended Harrow School and then spent a year in Russia with Wagau before moving to South Africa in 1894. This was a boom time for deep-level gold mining, mainly in the Jo’burg area. Raymond may have known about (or perhaps more than that) the ill-fated “Jameson Raid” in 1896. -

February 2020

The Sprout into Act ap ion Le ! Better Botley, better planet! The Botley and North Hinksey ‘Big Green Day’ Fighting ClimateSaturday Feb.Change 29th 10.30am in Botley – 4pm on 29th February Activities will include Children’s play activities and face painting ‘Dr. Bike’ cycle maintenance Seed planting and plant swap Entertainment, Photobooth, food and drink ‘Give and take’ - bring your unwanted books, Short talks on what we can do in our homes music and clothing and our community More information at: https://leap-into-action.eventbrite.co.uk The newsletter for North HinkseyABC & Botley Association for Botley Communities Issue 144 February 2020 1 The Sprout Issue 144, February 2020 Contents 3 Letters to the Editor Brownies Christmas Treats 5 Leap into Action 25 Botley Babies and Toddlers 9 Taekwondo for everyone 27 Our New Community Hall 13 the First Cumnor Hill 31 Recycling Properly 17 Dance-outs and Saturdads 35 Friendly Running Group 19 Planning Applications 37 Scouts festive fun 21 Eating to Save the Planet 41 Randoms 43 Local organizations From the Editor Welcome to the first Sprout of 2020! As befits a decade in which there is everything to play for on the climate front, this month’s offering has several articles designed to help us get into gear. Recycling properly (p 31) shows how to make your recycling effective. Eating to Save the Planet (p21) is an account of the third talk in Low Carbon West Oxford’s series Act Now. (The fourth will be on Avoiding Waste on 8th February.) LCWO is a priceless local resource, as is the waste-busting Oxford Foodbank. -

Cumnor Hill Character Assessment

Cumnor Hill Character Assessment Janet Craven, Kathryn Davies, Jan Deakin, Dudley Hoddinott, Rona Marsden, Tim Pottle & Chris Westcott ABSTRACT This document has been created by residents of Cumnor Hill, with additional input from Dr Kathryn Davies and supports the over-arching Character Assessment for Cumnor Parish. Cumnor Hill is one of the four wards that make up Cumnor Parish. To create the content of this document contributors used a combination of desk top research, field observations and interviews with local residents. In order to assess the area fully, the area has been split into 11 areas. This assessment was conducted between February and September 2017 as part of the set of documents that make up the evidence base of the Cumnor Parish Neighbourhood Plan. For further information, please visit www.cumnorneighbourhoodplan.co.uk or contact [email protected] Contents Page Notes Individual Character Assessments i. Chawley Lane 3 ii. Norreys Road & Bertie Road 6 iii. Cotswold Road 8 iv. Cumnor Hill to Chawley Lane 9 v. Cumnor Hill (Top) 10 vi. Delamare Rd & Estate 11 vii. Hurst Lane 13 viii. Kimmeridge Rd Estate 14 ix. Hid’s Copse Road 16 x. Oxford Road 18 xi. Clover Close 20 Added in May 2018 1 Cumnor Hill Character Assessment Page left intentionally blank 2 Cumnor Hill Character Assessment November 26, 2019 1 Chawley Lane SPACES: GAPS BETWEEN BUILT ELEMENTS – STREETS, GARDENS, ETC. Hints: Formal, building plots (size, building position, etc), means of enclosure, gaps, open, narrow, winding, straight, type of use, paving/surface materials, street furniture, usability, impact of traffic. Norreys Road and Bertie Road were developed as a consequence of the SCORE financial demise of the 4th Earl of Abingdon, who sold off this tract of land to : pay debts. -

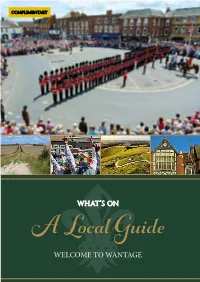

Welcome to Wantage

WELCOME TO WANTAGE Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com Welcome to Wantage in Oxfordshire. Our local guide is your essential tool to everything going on in the town and surrounding area. Wantage is a picturesque market town and civil parish in the Vale of White Horse and is ideally located within easy reach of Oxford, Swindon, Newbury and Reading – all of which are less than twenty miles away. The town benefits from a wealth of shops and services, including restaurants, cafés, pubs, leisure facilities and open spaces. Wantage’s links with its past are very strong – King Alfred the Great was born in the town, and there are literary connections to Sir John Betjeman and Thomas Hardy. The historic market town is the gateway to the Ridgeway – an ancient route through downland, secluded valleys and woodland – where you can enjoy magnificent views of the Vale of White Horse, observe its prehistoric hill figure and pass through countless quintessential English country villages. If you are already local to Wantage, we hope you will discover something new. KING ALFRED THE GREAT, BORN IN WANTAGE, 849AD Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com 3 WANTAGE THE NUMBER ONE LOCATION FOR SENIOR LIVING IN WANTAGE Fleur-de-Lis Wantage comprises 32 beautifully appointed one and two bedroom luxury apartments, some with en-suites. -

66 Chilswell Road Grandpont, Oxford, OX1 4PU 66 Chilswell Road Grandpont, Oxford, OX1 4PU

66 Chilswell Road Grandpont, Oxford, OX1 4PU 66 Chilswell Road Grandpont, Oxford, OX1 4PU D ESCRIPTION A period family home located to the south of Oxford city centre. This home as been extended by the current owner to create a well proportioned property offering a master bedroom with en-suite, three further double bedrooms and family bathroom on the upper two floors. The ground floor comprises a through double aspect reception room, cloakroom and a spacious kitchen/diner with French doors leading on to a west facing rear garden. Outside the rear garden has been landscaped to include a new lawn area and various flowerbeds. To the front there is a small walled garden area. LOCATION Situated in one of Grandpont’s sought after side roads and less than half a mile from Oxford City Centre, you will find the River Thames and tow path a short walk away. The location offers walking and a short bike riding distance to the train station and bus station with regular services to London and the airports. Tesco Express is a short walk away and there is a choice of local pubs and restaurants. The local primary school is St. Ebbes CE Primary School on Whitehouse Road, also within the catchment areas of both Cheney and Cherwell Secondary Schools. DIRECTIONS From Folly Bridge head south down Abingdon Road and take the fourth turning on the right Newton Road. Proceed along this road until Chilswell Road. Turn left and the property will be found on the right hand side. VIEWING ARRANGEMENTS Strictly by appointment with Penny & Sinclair. -

South Oxfordshire Zone Botley 5 ©P1ndar 4 Centre©P1ndart1 ©P1ndar

South_Oxon_Network_Map_South_Oxon_Network_Map 08/10/2014 10:08 Page 1 A 3 4 B4 0 20 A40 44 Oxford A4 B B 4 Botley Rd 4 4017 City 9 South Oxfordshire Zone Botley 5 ©P1ndar 4 Centre©P1ndarT1 ©P1ndar 2 C 4 o T2 w 1 le 4 y T3 A R A o 3 a 4 d Cowley Boundary Points Cumnor Unipart House Templars Ox for Travel beyond these points requires a cityzone or Square d Kenilworth Road Wa Rd tl SmartZone product. Dual zone products are available. ington Village Hall Henwood T3 R Garsington A420 Oxford d A34 Science Park Wootton Sandford-on-Thames C h 4 i 3 s A e Sugworth l h X13 Crescent H a il m d l p A40 X3 to oa R n 4 Radley T2 7 Stadhampton d X2 4 or B xf 35 X39 480 A409 O X1 X40 Berinsfield B 5 A 415 48 0 0 42 Marcham H A Abingdon ig Chalgrove A41 X34 h S 7 Burcot 97 114 T2 t Faringdon 9 X32 d Pyrton 00 7 oa 1 Abingd n R O 67 67A o x 480 B4 8 fo B 0 4 40 Clifton r P 67B 3 d a 45 B rk B A Culham R Sta Hampden o R n 114 T2 a T1 d ford R Rd d w D Dorchester d A4 rayton Rd Berwick Watlington 17 o Warborough 09 Shellingford B Sutton Long Salome 40 Drayton B B Courtenay Wittenham 4 20 67 d 67 Stanford in X1 8 4 oa Little 0 A R 67A The Vale A m Milton Wittenham 40 67A Milton 74 nha F 114 CERTAIN JOURNEYS er 67B a Park r Shillingford F i n 8 3 g Steventon ady 8 e d rove Ewelme 0 L n o A3 45 Fernham a G Benson B n X2 ing L R X2 ulk oa a 97 A RAF Baulking B d Grove Brightwell- 4 Benson ©P1ndar67 ©P1ndar 0 ©P1ndar MON-FRI PEAK 7 Milton Hill 4 67A 1 Didcot Cum-Sotwell Old AND SUNDAYS L Uffington o B 139 n Fa 67B North d 40 A Claypit Lane 4 eading Road d on w 1 -

Notice of Election Vale Parishes

NOTICE OF ELECTION Vale of White Horse District Council Election of Parish Councillors for the parishes listed below Number of Parish Number of Parish Parishes Councillors to be Parishes Councillors to be elected elected Abingdon-on-Thames: Abbey Ward 2 Hinton Waldrist 7 Abingdon-on-Thames: Caldecott Ward 4 Kennington 14 Abingdon-on-Thames: Dunmore Ward 4 Kingston Bagpuize with Southmoor 9 Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris Ock Ward 2 Kingston Lisle 5 Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris Wildmoor Ward 1 Letcombe Regis 7 Abingdon-on-Thames: Northcourt Ward 2 Little Coxwell 5 Abingdon-on-Thames: Peachcroft Ward 4 Lockinge 3 Appleford-on-Thames 5 Longcot 5 Appleton with Eaton 7 Longworth 7 Ardington 3 Marcham 10 Ashbury 6 Milton: Heights Ward 4 Blewbury 9 Milton: Village Ward 3 Bourton 5 North Hinksey 14 Buckland 6 Radley 11 Buscot 5 Shrivenham 11 Charney Bassett 5 South Hinksey: Hinksey Hill Ward 3 Childrey 5 South Hinksey: Village Ward 3 Chilton 8 Sparsholt 5 Coleshill 5 St Helen Without: Dry Sandford Ward 5 Cumnor: Cumnor Hill Ward 4 St Helen Without: Shippon Ward 5 Cumnor: Cumnor Village Ward 3 Stanford-in-the-Vale 10 Cumnor: Dean Court Ward 6 Steventon 9 Cumnor: Farmoor Ward 2 Sunningwell 7 Drayton 11 Sutton Courtenay 11 East Challow 7 Uffington 6 East Hanney 8 Upton 6 East Hendred 9 Wantage: Segsbury Ward 6 Fyfield and Tubney 6 Wantage: Wantage Charlton Ward 10 Great Coxwell 5 Watchfield 8 Great Faringdon 14 West Challow 5 Grove: Grove Brook Ward 5 West Hanney 5 Grove: Grove North Ward 11 West Hendred 5 Harwell: Harwell Oxford Campus Ward 2 Wootton 12 Harwell: Harwell Ward 9 1. -

Botley Character Statement West Way Community Concern

Botley Character Statement West Way Community Concern 1 Contents A. Introduction to the Botley Character Statement C. Headline Findings D. Location, Context and Layout E. Historical Development F. Character Areas 1. West Way 2. Old Botley 3. Seacourt 4. Westminster Way 5. Arthray Road 6. Cumnor Rise 7. North of West Way 8. Dean Court G. Sources Appendix A. Methodology 2 Section A. Introduction to the Botley Character Statement Local residents and businesses in Botley have joined together to prepare this character statement as a result of concern that new development should respond positively to the area’s established positive character. Local and national planning policies require proposals for new development to take local character into account and respond positively to it in the design of new buildings and spaces and their use. However, defining what the positive features of local character are that should be sustained and what negative feature should be managed out through development is a fundamental stage in this design process and requires assessment, analysis and establishment of consensus. Character assessments are now being undertaken by various community groups, as well as local planning authorities to establish this consensus about what is valued in the character of local areas and neighbourhoods to inform planning for change. To support local communities in undertaking their own assessment of character a number of toolkits have been prepared with the assistance of CABE and English Heritage. These are a recognised means for community groups to prepare character assessments that are sufficiently robust and reliable to be informative for planning decisions. -

Oxfordshire. Oxpo:Bd

DI:REOTO:BY I] OXFORDSHIRE. OXPO:BD. 199 Chilson-Hall, 1 Blue .Anchor,' sat Fawler-Millin, 1 White Hart,' sat Chilton, Berks-Webb, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Fawley, North & South-Gaskin, 'Anchor,' New road, Chilton, Bucks-Shrimpton, ' Chequers,' wed. & sat. ; wed. & sat Wheeler 'Crown,' wed & sat Fencott--Cooper, ' White Hart,' wed. & sat Chilworth-Croxford, ' Crown,' wed. & sat.; Honor, Fewcot-t Boddington, ' Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat 'Crown,' wed. & sat.; Shrimpton, 'Chequers,'wed.&sat Fingest--Croxford, ' Crown,' wed. & sat Chimney-Bryant, New inn, wed. & sat Finstock-:Millin, 'White Hart,' sat Chinnor-Croxford, 'Crown,' wed, & sat Forest Hill-White, 'White Hart,' mon. wed. fri. & sat. ; Chipping Hurst-Howard, ' Crown,' mon. wed. & sat Guns tone, New inn, wed. & sat Chipping Norton-Mrs. Eeles, 'Crown,' wed Frilford-Baseley, New inn, sat. ; Higgins, 'Crown,' Chipping Warden-Weston, 'Plough,' sat wed. & sat.; Gaskin, 'Anchor,' New road, wed. & sat Chiselhampton-Harding, 'Anchor,' New road, sat.; Fringford-Bourton, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Jones, 'Crown,' wed. & sat.; Moody, 'Clarendon,' sat Fritwell-Boddington, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Cholsey-Giles, ' Crown,' wed. & sat Fyfield-Broughton, 'Roebuck,' fri.; Stone, 'Anchor,' Cirencester-Boucher, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat New road, sat.; Fisher, 'Anchor,' New road, fri Clanfield-Boucher, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Garford-Gaskin, 'Anchor,' New road, wed Claydon, East, Middle & Steeple-Bicester carriers Garsington-Howard, ' Crown,' mon. wed. & sat. ; Dover, Cleveley-Eeles, 'Crown,' sat New inn, mon. wed. fri. & sat.; Townsend, New inn, Clifton-by-Deddington-Boddington, 'Anchor,' wed. & mon. wed. •& sat sat.; Weston, 'Plough,' sat Glympton-Jones, 'Plough,' wed.; Humphries, 'Plough,' Clifton Hampden-Franklin, 'Chequers,' & 'Anchor,' sat New road, sat Golden Ball-Nuneham & Dorchester carriers Coate Bryant, New inn, wed.