1 0 May 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[NSI1] NSI Region Map [Cab Sub Ver 3]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5750/nsi1-nsi-region-map-cab-sub-ver-3-425750.webp)

[NSI1] NSI Region Map [Cab Sub Ver 3]

er t To 55 t AP19782 Ap u p COUNTY Amity Point OF STANLEY ro 1 x AP19741 G t Cucumber Point AMITY e Low T r W (Pulan) o ate 60 a r M a USL20670 r k to C z Pelican A C 54 L o A Bank 19 Y a T AP19770 Flindersp Beach n O F l SL806442 N in S d p s e r L s e ro r DRIVE x v ROAD a BEACH B e t a H io ch i INDERS g n FL 152 POINT h P ge W a sa 118 r as at Approx Low Water Mar k k P SL9795 er o BEEHIVE T M ba ark B l e SL806436 wu ag 8 un ass USL32024 Rocky Point o u PEEL ISLAND P LOOKO W Finuge 566 u UT n CHIGGIL Cylinder Headland Deadmans Beach NPW834 d CHIGGIL Beach Cylinder Dune Rocks a 48 Sheet 2 E ROAD SL12352 r ri y c RO a k 3 AD TEERK ROO RA (PEEL ISLAND) r 1 USL32024 Frenchmans Pass a AP17595 BayPOINT LOOKOUT NATIONAL PARK age (Terrangee) L M 153 SL7991 E r 131 130 ROAD SP N e ROAD SL13002 North t 164078 Gorge 445 N . a Whale Rock . M 132 T W A COAST Point Lookout L . COAST SP164081 South o NPW834 Headland H W Lagoons A EAST 47 EAST Sheet 1 C h SP164076 p 46 p g 165 i SL SP164082 ro 9059 x rk e H a g r M a te ss x a a h W P o ig r H The Bluff L x p ro 63 o p p p a USL20278 72 w A lb 1 o a A SP212935 T i D USL32025 e 1 W g o CP815735 a T s a e s 152 61 a SL11761 t o h P e s Horseshoe r se r C Wildflower Refuge M o 100 o W SL806436 78 o r AP15913 H O o 74 a o e B n SL4247 r h Bay USL20278 N k T I A A a r r a R n o a o l r o a 200 . -

Annual General Meeting

Returned & Services League of Australia (Queensland Branch) Redlands Sub Branch Inc. ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Notice is hereby given to all Members of the Redlands RSL Sub Branch, that the Annual General Meeting will be held on Sunday 22nd March 2020, commencing at 10.00am sharp in the Gallipoli Room, 8 Passage Street, Cleveland. All Nominations for Committee Positions and Notices of Motion are to be submitted to the General Manager no later than 5pm, Friday 6th March 2020. AGENDA Business 1. President’s opening remarks 2. Apologies 3. Minutes of Previous Annual General Meeting 4. Business arising from the Minutes 5. President’s Report 6. Treasurer’s Report • Independent Auditor’s Report 7. General Manager’s Report 8. Wellbeing Report • Appointment of Pension Wellbeing Officers & Advocates 9. Library/Museum Report 10. Cadet Report 11. Election of Officers 12. Appointment of State RSL Delegates and SED Delegates 13. Appointment of Independent Auditors 14. General Business of which written notice has been received Peter S. Harrison General Manager President’s Report Fellow members, It’s wonderful weather for ducks. I think a little bit of a break could be in order, though I know the drought affected areas would say keep it coming, just a little bit slower. Our car park has proved very popular in this weather when patrons can come in and out in the dry. We are reaping the benefits of the revamp of our Cove Café, it has remained busy since the alterations. We have had many good comments about it. January proved to be a very good month as far as business is concerned, with almost all sections meeting budget. -

Benthic Inventory of Reefal Areas in Central Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Publication Information Center Phase 1: Benthic Inventory of Reefal Areas in Central Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia Report prepared for: Healthy Waterways By: Chris Roelfsema1,2, Jennifer Loder2, Rachel Host2, and and Eva Kovacs1,2 1) Remote Sensing Research Centre (RSRC), School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, AUSTRALIA, 4072 2) Reef Check Australia, Level 2 183 North Quay Brisbane, Queensland, AUSTRALIA 4000 Chris Roelfsema , Jennifer Loder, Rachel Host and Eva Kovacs March 2016 This project is supported by Reef Check Australia, through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Programme, and, the Port of Brisbane Community Grant Program. We would like to thank the volunteers who supported this project, including: Amanda Delaforce, John Doughty, Terry Farr, Sharon Ferguson, Stefano Freguia, Rachel Host, Tony Isaacson, Eva Kovacs, Jody Kreuger, Santiago Mejia, Jodi Salmond, Julie Schubert, Douglas Stetner. A note of appreciation to the Moreton Bay Research Station and Moreton Bay Environmental Education Centre for their support in fieldwork logistics, and, to Satellite Application Centre for Surveying and Mapping (SASMAC) for providing the ZY-3 imagery. Report should be cited as: C. Roelfsema, J. Loder, R. Host and E. Kovacs (2016) Phase 1: Benthic Inventory of Reefal Areas in Central Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia, Brisbane. Remote Sensing Research Centre, School of Geography, Environmental Management and Planning, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; and Reef Check Australia, Brisbane, Australia. Benthic Inventory of Reefal Areas, Central Moreton Bay 24 March 2016 1 Table of Contents: Table of Contents: .......................................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2017 / 2018

Our Story Ngaliya Maguydan Annual Report 2017 - 2018 Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation Annual Report 2017 - 2018 page 1 2 Contents& 3 Glossary & QYAC Activities for 2016 - 2017 5 About QYAC Bing wangan goorijin baje baru berren, 6 Message from the Chairperson & QYAC Board of Directors 7 Message from the CEO Yura. Barahn ngali Quandamooka jarala 9 Secure the Quandamooka Estate 1. Strengthen the organisation dandiyirri nyiyaba. 2. Complete the acquisition of Quandamooka Country We acknowledge the creator spirit and Elders 3. QALSMA land and sea management past and present. For today we meet and walk on 4. Achieve Indigenous Protected Area status 5. Achieve World Heritage Area status Quandamooka country. 33 Engage and Protect Quandamooka Knowledge 6. Knowledge is safely stored and accessible 7. Rights are protected 8. Elders are engaged 9. QALSMA develops policies and practices for Country 45 Become Self Sufficient Jarlo Jargu Boma artwork on cover and throughout by JOSHUA WALKER 10. Generate revenue streams Artwork was created in 2018 as part of the QYAC Jarlo Jargu Boma project 11. Strong financial strategy, planning, and growth 12. Build capacity of Quandamooka People to manage our estate Jandai language transcribed throughout by SANDRA DELANEY 13. Support the organisation through sub committees Language was transcribed in 2018 as part of the QYAC Indigenous Languages Preservation and Revival project 14. Generate systems, policies and procedures 15. Educate Traditional Owners about native title, land management and cultural -

2015 WQ Coastal Citizen Science Summary

Contents Introduction & Background Events & Partnerships Monitoring Achievements, Activities, Aims Acknowledgements 2 Introduction Why do we monitor? Seagrasses and mangroves are indicators of aquatic health and early indicators of change, so much so they’ve been dubbed ‘coastal canaries’. They are Introduction & coastal kidneys - trapping sediment and nutrients from the land which are Background harmful to the marine ecology. Mangroves reduce the erosive and potentially catastrophic effects of storm surges and tsunamis, doing so cheaper and better than man-made structures. And, mangroves and seagrasses sequester carbon - they have the ability to store carbon far more effectively than terrestrial forests. As a seafood-loving country we should know that over 70% of the fish, crabs and prawns we eat are reliant on mangroves and seagrasses during some stage of their life cycle. These ‘coastal canaries’ are habitat for large numbers of other species – biodiversity that have an intrinsic right to exist. Background Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland’s Coastal Citizen Science (WQCCS) coordinates MangroveWatch (MW) and SeagrassWatch (SGW) in and around Moreton Bay, its rivers and creeks. These scientifically rigourous programs were devised by scientists from James Cook University and are conducted globally. Citizen science is broadly defined as the involvement of volunteers in the collection of data for scientific purposes. Teaming volunteers with the scientific community in this way provides important data that would not otherwise be available. Training provided by the scientists and ongoing quality assessment of the data collected ensures the validity of the data for scientific assessment. The data can then be used by natural resource managers and other decision-makers to guide investment and to undertake preventative measures and restorative actions. -

Things to Do in Redland City

THINGS TO DO IN REDLAND CITY LOCAL TOURISM PROVIDERS BAY ISLAND SUP COMPANY 0408 592 754 COOCHIE BOAT AND BIKE HIRE (07) 3207 8207 MACLEAY ISLAND BIKE HIRE 0408 003 198 Experience the world’s fastest growing water Coochie Boat Hire on Coochiemudlo Island is What better way to discover the Southern sport on beautiful Moreton Bay! Stand up just a 10 minute ferry ride from Victoria Point. Moreton Bay Islands than by push bike? With paddle board hire & lessons at Raby Bay Coochie Boat and Bike Hire have a range of a range of bikes for hire from mountain bikes Foreshore in Cleveland. fun and exciting equipment on hire to to kid’s bikes right through to tandem bikes www.bayislandsup.com.au maximise your experience whilst on the Macleay Island Bike Hire will have the bike for island. you! REDLANDS KAYAK TOURS 1300 KAYAK TOUR www.coochieboathire.com www.macleayislandbikehire.blogspot.com.au/ Theres no better way to experience Moreton Bay than in your very own personalised kayak CLEVELAND AQUATIC CENTRE (07) 3286 2723 POPULAR WALKS tour. Redlands Kayak Tours offer a unique way The Cleveland Aquatic Centre has a range of GORGE WALK – WHALE WATCHING to experience the bay for the inexperienced facilities to cater for people of many ages, The 1.2km Gorge Walk at Point Lookout on kayakers to the well established kayaker. these include 25m and 50m lap pool, gym and North Stradbroke Island is the perfect location www.redlandskayaktours.com.au kids adventure playground with rapid ride and to spot abundant marine life such as turtles, spa. -

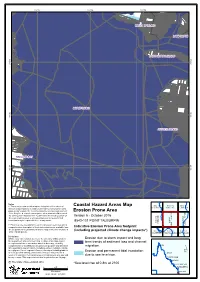

Point Talburpin S R N S I U O

153.32 153.34 153.36 MACLEAY ISLAND LAMB ISLAND KARRAGARRA ISLAND 4 4 6 6 . 7 7 2 2 - - MORETON BAY 6 6 6 6 . 7 7 2 2 - - RUSSELL ISLAND REDLAND BAY 8 8 6 6 . 7 7 2 2 - - Notes 1. The areas shown on this map are indicative of the extent of Coastal Hazard Areas Map 9542-143 9542-142 9542-113 REDLAND BAY MACLEAY CANALPIN erosion and permanent inundation defined by erosion prone area plans declared under the Coastal Protection and Management Act Erosion Prone Area N D I P 1995. Only the declared erosion prone area plans should be used N A R D 4 1 4 L U for development assessment. To determine the actual position of 3 3 2 Version 6 - October 2016 N S B I 1 1 1 A - - - L the erosion prone area a registered surveyor or geotechnical L L 2 2 2 A L 4 4 4 D T consultant may be required if there is any doubt. E 5 5 5 E T 9 9 9 9542-131 POINT TALBURPIN S R N S I U O 2. Erosion prone area plans for each local government area and a R P comprehensive description of their determination are available from Indicative Erosion Prone Area footprint the Department of Environment and Heritage Protection website at (including projected climate change impacts*) 9542-133 9542-132 9542-123 www.ehp.qld.gov.au GILBERTON WOONGOOLBA SHORT ISLAND Disclaimer Whilst every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this product, Erosion due to storm impact and long the Department of Environment and Heritage Protection makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, term trends of sediment loss and channel WEIPA completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and disclaims migration. -

(Alcheringa) Island Macleay Island Russell (Canaipa) (Alcheringa

Follow the trail... MAP MORETON BAY MAP 7 MAP 1 (QUANDAMOOKA) 2 2 Coochiemudlo Island 6 MOOROONDU STST 1 Island transport Passage Mangroves 2 Pioneer Park SCALE Coochiemudlo Macleay DR 0 500 EROBIN ST 3 Scar trees Laurie Burns Recreation Reserve metres ST 4 Norfolk Beach Melaleuca 4 MORETON BAY PDE Island Lamb Island 5 Melaleuca wetlands CAPEMBAH ST Wetlands (QUANDAMOOKA) 5 6 8 5 (Alcheringa) Morwong Beach Mangroves Island (Nguderoo) PERULPA Paula Pde 7 Track and observation lookout ST 4 Pine Ave Doug & Mary VICTORIA Burns Point Morton PDE 8 Morton’s steps and jetty PDE Reserve Lucas 11 LUCAS 9 Flinders Lookout ELIZABETH VICTORIA Tina Ave SCALE 10 TAGERUBAPDE 0 500 10 2 3 1 3 Coochiemudlo Island Community Hall 9 VICTORIA Main Beach 2 metres 11 Golf course 1 Passenger & vehicular ferry service (Victoria Point) Passenger & vehicular ferry service (Redland Bay) Lamb Island Potts Point Coochiemudlo I. Passenger & vehicular ferry service (Redland Bay) 1 Lamb Island jetty shed Karragarra 8 (Coondooroopa) Kibbinkibbinwa Pt (Coondooroopa) MAP Island Kibbinkibbinwa Pt 2 Thomas Lucas grave MORETON BAY Beelong St 1 Krummel POINT e DR 10 g Ooncooncoo A MAP a P 3 (QUANDAMOOKA) Victoria Pass I Mango trees and farmhouse 3 3 Bay A ST Point Macleay 4 1 CAN ge 4 Lamb Island Pioneer Hall MAP sa 2 as 5 Dalpura Cavendish 2 P Harry Brook Reserve, house and farm buildings Cow Bay ST Island Lamb CANAIPA RD Beach Redland Island Macleay Island 9 Bay 5 Cestrum St Karragarra I. 6 9 a 1 Ron Field Marine Facility Kings Rd ip Pannikin Laurel St St a Willes Island Willes Cuphea St n 2 Progress Hall Russell I. -

Bird Places of the Redlands

Wildcare Phone (07) 5527 2444 5527 (07) Phone Wildcare Spangled Drongo*, Leaden Flycatcher, Mistletoebird. Flycatcher, Leaden Drongo*, Spangled Get help for injured native birdlife native injured for help Get Woodswallow, Grey Shrike-thrush, Golden Whistler, Olive-backed Oriole*, Oriole*, Olive-backed Whistler, Golden Shrike-thrush, Grey Woodswallow, Honeyeater, White-throated Honeyeater, Mangrove Gerygone, White-breasted White-breasted Gerygone, Mangrove Honeyeater, White-throated Honeyeater, eater*, Pale-headed Rosella, Scaly-breasted Lorikeet, Dollarbird*, Mangrove Mangrove Dollarbird*, Lorikeet, Scaly-breasted Rosella, Pale-headed eater*, Dove, Eastern Koel*, Sacred Kingfisher*, Torresian Kingfisher, Rainbow Bee- Rainbow Kingfisher, Torresian Kingfisher*, Sacred Koel*, Eastern Dove, www.redland.qld.gov.au/info/20118/paths_trails_and_cycleways and Redland City Council City Redland and Whimbrel*, Eastern Curlew*, Crested Tern, Bar-shouldered Dove, Peaceful Peaceful Dove, Bar-shouldered Tern, Crested Curlew*, Eastern Whimbrel*, cycleways of the Redlands Redlands the of cycleways Kite, Bush Stone-curlew, Australian Pied Oystercatcher, Black-winged Stilt, Stilt, Black-winged Oystercatcher, Pied Australian Stone-curlew, Bush Kite, A collaborative project by BirdLife Southern Queensland Queensland Southern BirdLife by project collaborative A Egret, Striated Heron, Royal Spoonbill, Osprey, Whistling Kite, Brahminy Brahminy Kite, Whistling Osprey, Spoonbill, Royal Heron, Striated Egret, Please visit this website to view all paths, trails and and trails paths, all view to website this visit Please Pied Cormorant, Australasian Darter, Great Egret, White-faced Heron, Little Little Heron, White-faced Egret, Great Darter, Australasian Cormorant, Pied A car is recommended to explore Russel and Macleay Islands. Macleay and Russel explore to recommended is car A across the Bay to the islands. Explore by foot on Karragarra or Lamb Islands. -

Reef Check Australia South East Queensland Season Summary Report 2016-2017

Reef Check Australia South East Queensland Season Summary Report 2016-2017 Reef Check Foundation Ltd M. Welch, J. Salmond. J. Passenger, R. Pentti and J. Loder www.reefcheckaustralia.org 2017 This project was made possible by a network of dedicated volunteers, generous dive operators, wise advisors, innovative collaborators and supportive funding agencies. Snorkel transects were monitored in partnership with Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation and Quandamooka Land and Sea Management Agency. Thank you to the dedicated citizen scientists who have contributed to survey activities: Jeremiah Abberdan, Graeme Bulley, Isaac Burns, Corinna Byrne, Nathan Caromel, Lucas Close, Paul Colquist, Patrick Coolwell, Amanda Delaforce, Philip Dunbavan, Terry Farr, Shawn Fisher, Stefano Freguia, Josh Hansen, Eva Kovacs, Jacob Martin, Michael Mears, Santiago Mejia, Lauren Morgan, Michael Nothling, Josh Passenger, Julie Schubert, Douglas Stetner, Jacob Tippo, Hannaleena Väisänen, Breanne Vincent. A special note of acknowledgement to our trainers, professional volunteers and staff: Jody Kreuger, Jennifer Loder, Jodi Salmond, Chris Roelfsema and Rebekka Pentti Many of the images used within this document were taken by Reef Check Australia Community Engagement Manager Jodi Salmond. We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land on which project activities were conducted, and pay our respects of Elders past, present and future. This project is supported by Reef Check Australia, through funding from the Sunshine Coast Council, Healthy Land and Water, and The Great Barrier Reef Foundation with the Great Barrier Reef Citizen Science Alliance as part of ReefBlitz 2016. This report should be cited as: M.Welch, J. Salmond, J. Passenger, R. Pentti and J. Loder South East Queensland Season Summary Report 2016. -

Review Report Template

Victoria Point State High School Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Review team ................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 School context ............................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Contributing stakeholders ............................................................................................ 5 1.4 Supporting documentary evidence............................................................................... 5 2. Executive summary ........................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Key findings ................................................................................................................. 6 2.2 Key improvement strategies ........................................................................................ 9 2 1. Introduction This report is a product of a review carried out by a review team from the School Improvement Unit (SIU) at Victoria Point State High School from 25 to 28 June 2018. The report presents an evaluation of the school’s performance against the nine domains of the National School Improvement Tool. It also recommends improvement strategies for the school to consider in consultation with its regional office and school community. The report’s executive summary outlines key findings -

Reef Check Australia South East Queensland Survey Season

Reef Check Australia South East Queensland Season Summary Report 2012 ©Ian Banks Reef Check Foundation Ltd J. Loder, A. Bauer, K. Grealy and K. Trim Edited by J. Salmond www.reefcheckaustralia.org Released May 2013 Reef Check Australia greatly appreciates all of the people and organizations who have helped to make this project a success. A big thank you to our dedicated volunteers, generous dive operators, innovative collaborators and supportive funding agencies. Huge thank you to the dedicated volunteers who have joined us on a survey this year: Christine Bueta, Sophie Clay, Paul Evans, Terry Farr, David Glover, Alex Grand, Alex Lea, Justin Marriner, Katherine Trim, Julie Schubert, Doug Stetner, Vanessa Taveras. A special note of acknowledgement to our trainers and staff: David Glover, Pete Faulkner, Jody Kreuger, Jodi Salmond and Chris Roelfsema. This project is supported through funding from the Australian Government's Caring for our Country, Sunshine Coast Council and Redland City Council. Thank you to Reef Check supports who provided in-kind donations to help make this survey season a success, including Dive Noosa, Dive World, Go Dive, Manta Lodge & Scuba Centre, MicroMarine, Nautilus Scuba Centre, Point Lookout Scuba Dive Charters, Scuba World, SEQ Catchments, Sun Reef, University of Queensland and University of the Sunshine Coast. This report should be cited as: J. Loder, A. Bauer, K. Grealy and K. Trim (2013). Reef Check Australia South East Queensland Season Summary Report 2012. Reef Check Foundation Ltd. Table of Contents Introduction