Personal Liability of Corporate Officials in Ejectment Actions: Evolution of the Tort and the Implications of Metromedia Co

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

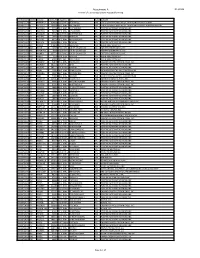

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Attachment a DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing

Attachment A DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing File Number Service Callsign Facility ID Frequency City State Licensee 0000072254 FL WMVK-LP 124828 107.3 MHz PERRYVILLE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMN. 0000072255 FL WTTZ-LP 193908 93.5 MHz BALTIMORE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 0000072258 FX W253BH 53096 98.5 MHz BLACKSBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072259 FX W247CQ 79178 97.3 MHz LYNCHBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072260 FX W264CM 93126 100.7 MHz MARTINSVILLE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072261 FX W279AC 70360 103.7 MHz ROANOKE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072262 FX W243BT 86730 96.5 MHz WAYNESBORO VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072263 FX W241AL 142568 96.1 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072265 FM WVRW 170948 107.7 MHz GLENVILLE WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072267 AM WESR 18385 1330 kHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072268 FM WESR-FM 18386 103.3 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072270 FX W289CE 157774 105.7 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072271 FM WOTR 1103 96.3 MHz WESTON WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072274 AM WHAW 63489 980 kHz LOST CREEK WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072285 FX W206AY 91849 89.1 MHz FRUITLAND MD CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. 0000072287 FX W284BB 141155 104.7 MHz WISE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072288 FX W295AI 142575 106.9 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072293 FM WXAF 39869 90.9 MHz CHARLESTON WV SHOFAR BROADCASTING CORPORATION 0000072294 FX W204BH 92374 88.7 MHz BOONES MILL VA CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. -

Baltimore Convention Center

FEBRUARY 16, 17 & 18, 2018 2018 BALTIMORE CONVENTION CENTER YOU’RE INVITED! Jump-start Your Business in 2018 at the Upscale Baltimore Remodeling Expo! Looking for the perfect way to jump-start your business in 2018? Then be sure to exhibit your home improvement solutions to thousands of focused and motivated homeowners at the upscale Baltimore Remodeling Expo! A “MUST ATTEND” EVENT Produced by L&L Exhibition Management, the Baltimore Remodeling Expo is timed to help you generate key projects and new customers for the 2018 selling season. UPSCALE ENVIRONMENT The show will take place on February 16, 17 & 18, 2018 at the Baltimore Convention Center. For three days, As an exhibitor, you can look forward to: Generating quality leads from a pool of focused and highly motivated homeowners Meeting Baltimore-area homeowners with a strong interest in home improvement, face-to-face Taking your place among the region’s top home and garden professionals Showcasing your products in a quality trade show environment Quite simply, the Baltimore Remodeling Expo is a must-attend event for home improvement professionals in Baltimore and the surrounding area. COMPREHENSIVE ADVERTISING COVERAGE To spread the word and attract homeowners who are looking for solutions that you offer, the Baltimore Remodeling Expo will be aggressively advertised via TV, newspaper, online and radio, including: WCBM-AM, WQSR-FM, WPOC-FM, WLIF-FM, WJZ-AM, WJZ-FM, WBAL-AM, WZBA-FM, WWMX-FM, WJZ, WBAL, WMAR, WBFF, and cable stations. PROFESSIONAL & PROVEN MANAGEMENT Now in our 24th year, L&L Exhibition Management is renowned across the country for producing high-prole, high- trafc events that showcase leading home improvement professionals and rms as well as the latest and most innovative products in the home improvement and home building industries. -

183-204Mbbguide.Pdf

“STRIVE FOR CLARITY, BUT ACCEPT AND UNDERSTAND AMBIGUITY. That phrase captures one way in which an educated person approaches the world and its challenges. Students who graduate from the University of Maryland have been exposed to the tools that allow them to put that perspective to work. Imparting such a perspective may be an ambitious project for undergraduate education, but to aim for anything less would be unworthy of a great university’s goals for its students. Thirteen years ago, Promises to Keep, a plan for undergraduate education at Maryland, articulated those goals so eloquently we repeat them here. Undergraduate education at Maryland “aims to provide students with a sense of identity and purpose, a concern for others, a sense of responsibility for the quality of life around them, a continuing eagerness for knowledge and understanding, and a foundation for a lifetime of personal enrichment.” As we learn with and from one another, we try to “develop human values,” “celebrate tolerance and fairness,” “contribute to the social conscience,” “monitor and assess private and collective assumptions,” and “recognize the glory, tragedy and humor of the human condition.” Your years at the University of Maryland can provide you with all the tools you need to accomplish these goals. Students here are “educated to be able to read with perception and pleasure, write and speak with clarity and verve, handle numbers and com pu ta tion proficiently, reason mathematically, generate clear questions and find probable arguments, reach substantiated conclusions and accept ambiguity.” AND WE ALSO HOPE YOU ENJOY THE JOURNEY. FEAR THE TURTLE 184 2005-06 MARYLAND MEN’S BASKETBALL UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND THE CAMPUS LIBRARIES By virtually every measure of quality, the University of Maryland has gained national Seven libraries make up the University of Maryland library system: McKeldin (main) Library, recognition as one of the fastest-rising comprehensive research institutions in the country. -

RA Nov 1925 .Pdf

Blue rin ectionorr Every Mont g! sá iiRk ?t gA/ú i 0 0v4 ayèAa: MEET Y FACTS BOOMERANG CRITICISM THE "WHY OF THE SIX" The Silver Six is at once the most satisfactory and the most unusual as described in Radio Broadcast of November and December broadcast receiver ever devised. It is the first practical receiver with Sensitivity, Selectivity Tonal Quality which cannot be surpassed. SELECTIVITY is such that out of town stations and may be brought to Chicago through twelve powerful This can only be understood by a careful study of the receiver's charac- local stations. Selectivity can be regulated at will, teristics as analyzed under "FACTS." from a degree satisfactory for ordinary reception, up to the surprising limit where side -bands arc cut. The Silver Six was put through its paces for a prominent Editor, SENSITIVITY is so great that nothing will sur- pass the Six" except special laboratory-build an Engineer and an Executive just after it was perfected. How super -heterodynes. Either coast may be brought did they react? The Editor asked to have the tuning broadened in to Chicago during the summer months on a small antenna -in many cases on a loop. The Engineer was astonished at the uncanny ability to bring in DX FLEXIBILITY permits the use of antenna or Stations in daylight . The Executive objected to the intensity loop with either detector, one or both stages of with which low on scale were Why radio frequency amplification. Interchangeable notes the musical reproduced. R. F. Transformers, with adjustable antenna coup- did these men react this way? Simply because the Silver Six was not ler, permit operation on all waves from 50 to 550 "just another receiver" of merit easily recognized in comparison with or higher if desired. -

PUBLIC NOTICE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION 445 12Th STREET S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION 445 12th STREET S.W. WASHINGTON D.C. 20554 News media information 202-418-0500 Internet: http://www.fcc.gov (or ftp.fcc.gov) TTY (202) 418-2555 Report No. SES-02122 Wednesday December 12, 2018 Satellite Communications Services Information re: Actions Taken The Commission, by its International Bureau, took the following actions pursuant to delegated authority. The effective dates of the actions are the dates specified. SES-AMD-20180922-02818 E E181663 WIS License Subsidiary, LLC Amendment Grant of Authority Date Effective: 12/10/2018 Class of Station: Fixed Earth Stations Nature of Service: Fixed Satellite Service SITE ID: 1 LOCATION: 1111 Bull St., Richland, Columbia, SC 34 ° 0 ' 7.80 " N LAT. 81 ° 1 ' 45.90 " W LONG. ANTENNA ID: 1 4.5 meters SSE 8345 3700.0000 - 4200.0000 MHz 36M0G7W Digital Video Carrier ANTENNA ID: 2 4.5 meters SSE 8345 3700.0000 - 4200.0000 MHz 36M0G7W Digital Video Carrier ANTENNA ID: 3 3.7 meters 37DH1 37DH1 3700.0000 - 4200.0000 MHz 36M0G7W Digital Video Carrier ANTENNA ID: 4 3.7 meters 3.7/PR12 3.7/PR12 3700.0000 - 4200.0000 MHz 36M0G7W Digital Video Carrier ANTENNA ID: 5 3.1 meters PRT-310 PRT-310 Page 1 of 68 3700.0000 - 4200.0000 MHz 36M0G7W Digital Video Carrier Points of Communication: 1 - PERMITTED LIST - () SES-AMD-20180924-02881 E E181689 WVUE License Subsidiary, LLC Amendment Grant of Authority Date Effective: 12/10/2018 Class of Station: Fixed Earth Stations Nature of Service: Fixed Satellite Service SITE ID: 1 LOCATION: 1450Poydras St, Orleans Parish, New Orleans, LA 29 ° 56 ' 58.00 " N LAT. -

Garden Sense the Most Listened to Syndicated Garden Show 2018

Garden Sense The Most listened to Syndicated Garden Show 2018 network stations WMCA 570am New York Saturdays 10:00- 11:00 am WTEL 610 am Philadelphia Saturday 9:00 - 10:00 am WIND 560 AM Chicago, IL, Sunday 11:00-12:00 WMAL 630AM Washington DC/Baltimore, MD, Saturday 8:00-9:00 WWDB 860 AM, Philadelphia, Pa Saturday 8:00-9:00 AM & Sunday 7:00-8:00 AM WPHT 1210 AM Philadelphia PA, Saturday 6:00-7:00 AM WHYN AM 560: Springfield Ma Saturday 8:00-9:00 am WHMP FM 96.9: North Hampton Ma Saturday 7:30-8:30 am & Sunday 6:00-7:00 am WHMP AM 1400: North Hampton Ma Saturday 7:30-8:30 am & Sunday 6:00-7:00 am WHMQ AM 1240: Greenfield Ma Saturday 7:30-8:30 am & Sunday 6:00-7:00 am WHNP AM 1600: Springfield Ma Saturday 7:30-8:30 am & Sunday 6:00-7:00 am WHNP AM 1600: Springfield Ma Saturday 7:30-8:30 am & Sunday 6:00-7:00 am WITK AM 1550:Wilkins-Barre/Scranton Pa Saturday 8:30-9:30 am WYYC AM 1250:York Pa Saturday 12:30-1:30 pm WSKY AM 1230: Asheville NC Saturday 8:00-9:00 am WELP AM 1360: Greenville SC Tuesday 7:30-8:30 pm WBXR AM 1140: Huntsville AL Saturday 6:30-7:30 am WFAM AM 1050: Augusta Ga Saturday 6:00-7:00 am WCPC AM 940:Tupelo MS Saturday 9:00-10:00 pm WKGM AM 940: Norfolk Va beach Sunday 4:00-5:00 pm WKDI AM 840: Denton Md Saturday 8:00-9:00 am WKNV AM 890: Blacksburg Va Saturday 11:00-12:00 noon WCBX AM 900: Roanoke VA Sunday 8:00-9:00 am WBGS AM 1030: Point Pleasant WV Sunday 10:00-11:00 am WLGN AM 1510: Logan Ohio Saturday 8:00-9:00 WIHY AM 1110: Hurricane WV Saturday 11:00-12:00 noon WYHY AM 1080: Ashland Ky Saturday 11:00-12:00 noon -

University of Baltimore IV-7.1 Inclement Weather Policy

University of Baltimore IV-7.1 Inclement Weather Policy A. Consistent with USM 170.0 VI-12.00-Policy on Emergency Conditions: Cancellation of Classes and Release of Employees, the University President has the authority to cancel or otherwise modify class and work schedules because of emergency conditions that may arise because of inclement weather, fire, power failure, civil disorder or other unusual circumstances which may endanger students or employees. B. Safety is always the number one priority relative to opening or closing announcements, and we endeavor to make those announcements in a timely fashion. In the Mid-Atlantic region trying to get a handle on the weather is always problematic. The snow totals can range from 1 inch in the west to 11 inches in the south and east. The decision to close or delay during periods of inclement weather is not taken lightly; local and regional forecasts are consulted, condition of state roads, as reported by the Maryland Department of Transportation, the Maryland Transportation Authority, the Maryland State Police, and the Baltimore City Office of Emergency Management are evaluated prior to making a decision about modifying class and work schedules. Moreover, announcements of other area colleges and universities about their own plans are also reviewed and discussed by administrators. In addition, conditions involving the safety and availability of university parking facilities and the condition of the streets adjacent to the university are also assessed. Administrators recognize that weather conditions 20 miles west of UB could be quite different than conditions at the campus. Nevertheless, the final decision rests with the University's goal of accommodating as many of its campus members as possible on a given day. -

Final Report Maryland Health Benefit Exchange

WEBER SHANDWICK 10.25.10 Final Report Maryland Health Benefit Exchange Contract No. DHMS296492 November 2011 Contents Task Description 3 Executive Summary 4 Campaign Objectives 7 Audiences 8 Strategic Approach 25 Messaging 37 Branding the Exchange 44 Creative Development 48 Partnerships 58 Earned Media / Public Relations 69 Paid Advertising 77 Social and Digital Media 88 Community Outreach / Education 96 Methodology for Organizing Marketing and Messages 104 Informational Materials 108 Risk Management and Response 113 Measurement and Evaluation 117 Timeline 123 Budget Level Options 127 APPENDIX A: Environmental Scan and Market Analysis APPENDIX B: Community Outreach – Sample Target Organizations and Groups APPENDIX C: Earned Media – Sample Target Media Outlets APPENDIX D: Potential Partnerships – Sample Potential Partners APPENDIX E: Materials from Massachusetts Health Connector Campaign 2 Task Description On April 12, 2011, Governor O’Malley signed into law the Maryland Health Benefit Exchange Act that established the Exchange as a public corporation and an independent unit of State government. The Act requires the Maryland Health Benefit Exchange (Exchange) to study and make recommendations on several issues, including how the Exchange should conduct its public relations and advertising campaign. The Exchange created an advisory committee on Navigator and Enrollment Assistance that is charged with considering options for the Exchange’s outreach efforts as well as its Navigator Program and enrollment efforts. Weber Shandwick and its research division, KRC Research, was charged with providing to the advisory committee the analytic support to study and make recommendations regarding how the Exchange should conduct its public relations and advertising campaign. Analysis included consideration of the population and environment of Maryland based on existing national and state information, utilizing existing data sources. -

BOWIE STATE UNIVERSITY School Counseling Program Handbook

BOWIE STATE UNIVERSITY School Counseling Program Handbook Bowie State University is the only public institution in Maryland with CACREP accreditation for Mental Health Counseling and School Counseling programs. Department of Counseling College of Education 2019-2020 Table of Contents Welcome and Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 University Mission and Vision Statements .................................................................................................................... 3 University Core Values .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 University Accreditation .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Program Accreditation ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 College of Education Mission Statement ...................................................................................................................... 4 Program Mission ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 Program Descriptions, Goals and Objectives ............................................................................................................. -

University of Maryland

1 9 4 THE UNIVERSITY University of Maryland DEEP ROOTS BROAD IMPACT Charles Benedict Calvert founded the Maryland Agricultural College in 1856 with the goal of creating a school that would offer outstanding practical knowledge to him and his neighbors and be “an institution superior to any other.” One hundred and fifty years later, the University of Maryland has blossomed from its roots as the state’s first agricultural college and one of America’s original land grant institutions into a model of the modern research university. It is the state’s greatest asset for its economic development and its future, and has made its mark in the nation and the world. Calvert would be astounded by the depth and breadth of research activities, innovative educational programs, and the single-minded pursuit of excellence that are part of the University of Maryland today. Maryland is ranked 18th among the nation’s top public research universities by U.S. News & World Report, with 31 academic programs in the Top 10 and 86 in the Top 25. It is also ranked No. 37th in the world, according to the Institute of Higher Education at at Shanghai’s Jiao Tong University. 2008 FOOTBALL MEDIA & RECR U I T I N G G U IDE 1 9 5 Maryland is the state’s premier center of research and is Mideast peace, cutting-edge research in nanoscience, graduate education and the public institution of choice homeland security or bioscience advances, Maryland faculty for undergraduate students of exceptional ability and are selected for national leadership and are making news. -

Inclement Weather Presentation 2020

Inclement Weather Procedures October 21, 2020 Carla Viar Pullen Office of Supporting Services Queen Anne's County Public Schools Preparing World-Class Students Through Everyday Excellence Purpose To explain the process of how Queen Anne’s County Public Schools determines when to implement the following due to inclement weather. Objective To educate the community on how Queen Anne’s County Public Schools determines whether schools will be opening late, closing early, or closed for the day due to inclement weather. Sources of Weather Information ▶ AccuWeather ▶ National Weather Service (Mount Holly) ▶ Local Media Weather Outlets (WBAL, WMAR, WJZ, & WBOC) ▶ National Media Weather Outlets (Weather Channel) ▶ Maryland Emergency Management Agency (MEMA) ▶ Weather Underground Website Weather Forecast Models ▶ NAM (North American Mesoscale) ▶ GFS (Global Forecast System) ▶ RUC (Rapid Update Cycle) ▶ RAP (Rapid Refresh) ▶ ECMWF (European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) Information Obtained from Various Sources ▶ Maryland State Police “Centreville Barrack” ▶ Queen Anne’s County Sheriff’s Office ▶ Queen Anne’s County Emergency Management Services ▶ Queen Anne’s County Public Works ▶ Queen Anne’s County Department of Parks ▶ Maryland State Highway Administration ▶ QACPS Spotters (Contracted and County Bus Drivers) ▶ SHA Traffic Cameras ▶ QACPS Exterior Cameras (Parking lots and Sidewalks) Temperature and Visibility Readings Weather Spotters (Bus Contractors & County Drivers) Timeline for Delay or Closing- Standard School Year ▶ 3:30AM -