An Account and Analysis of Three Critical Periods in the WNBA's Young History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girls-Basketball-Records.Pdf

ALL-TIME GIRLS BASKETBALL CHAMPIONS ALL DIVISIONS 1974 - 1988 Year Div. Champion Head Coach Score Runner-up Site 1974 4-A Mira Costa Sylvia Holly 39-32 Santiago Santa Fe HS 1975 4-A Santiago Judy Loundagin 42-33 Alemany Cal State Fullerton 3-A Santa Maria Joan Edwards 36-33 Valley Christian/Cerritos Cal State Fullerton 1976 4-A Ventura Chuck Shively 51-37 Crescenta Valley Cal State Fullerton 3-A El Dorado Linda Anderson 65-40 Righetti Cal State Fullerton 2-A Central John Cormann 45-39 Brawley Imperial Valley College 1977 4-A Huntington Beach Joanne Kellogg 77-60 St. Joseph/Lakewood Cal State Fullerton 3-A Righetti Cindy Hasbrook 52-49 Upland Cal State Fullerton 2-A Bishop Diego Linda Dawson 52-49 Brawley Imperial Valley College 1978 4-A Huntington Beach Joanne Kellogg 50-41 Buena Long Beach City College 3-A Righetti Judy McMullen 55-46 Upland Long Beach City College 2-A Alta Loma Mary Pollock 51-36 Santa Clara Long Beach City College 1-A Bishop Diego Linda Dawson 38-33 Valley Christian/Cerritos Long Beach City College 1979 4-A Buena Joe Vaughan 44-25 Dos Pueblos Cal Poly Pomona 3-A Riverside Poly Ralph Halle 54-44 Alta Loma Cal Poly Pomona 2-A Gahr Tom Pryor 50-48 Brawley Cal Poly Pomona 1-A Culver City Warren Flannigan 40-39 Ontario Christian Cal Poly Pomona SS Shandon Jane Peck 41-33 Orange Lutheran Atascadero HS 1980 4-A Riverside Poly Floyd Evans 64-48 Long Beach Poly Long Beach Arena 3-A Alta Loma Harvey Lovitt 66-52 Estancia Long Beach Arena 2-A Esperanza Cec Ponce, 60-45 Mayfair Long Beach Arena Dan Dessecker 1-A Ontario Christian -

Brag Sheet.Indd

SEC Women’s Basketball The Nation’s Premier Women’s Basketball Conference With EIGHT na onal championships, ten runner-up fi nishes, a Along with the eight NCAA championships won by Tennessee; Ar- na on-leading 34 Final Four appearances and 113 fi rst-team kansas (1999) and Auburn (2003) captured the current Women’s All-America honors, the SOUTHEASTERN CONFERENCE stands NIT tles. But the fi rst-ever SEC na onal tle belongs to Georgia, fi rmly as the na on’s premier intercollegiate women’s basketball winners of the 1981 NWIT which predates the current WNIT tour- conference. nament. Vanderbilt (1984), LSU (1985) and Kentucky (1990) also won NWIT tles. As members of their previous conferences Ar- SEC BY THE NUMBERS kansas (1987), South Carolina (1979) and Texas A&M (1995) won the WNIT, while Texas A&M (2011) won the NCAA tle prior to • The SEC has posted impressive non-conference records in the joining the SEC. last decade. The SEC compiled a 168-45 (.788) non-conference re- cord during the 2013-14 season. • In 2003, Auburn won the WNIT tle with wins over South Ala- bama, Florida State, Richmond, Creighton and Baylor. In 1999, the • Since the 1990 season, the SEC has compiled a 3471-1029 (.771) Arkansas Lady Razorbacks defeated Wisconsin 76-64 to claim the record against other conferences. The league has recorded 150+ SEC’s fi rst WNIT championship. wins during 10 seasons and has never recorded a non-conference winning percentage below .723. • In 1981, Georgia defeated Pi sburg, California and Arizona State (in OT) to capture the NWIT Championship, the fi rst-ever na onal • SEC teams have earned appearances in 25 of 33 NCAA Final championship of any kind for the SEC in women’s basketball. -

History & Records

NOTRE DAME FIGHTING IRISH 2016-17 WOMEN’S BASKETBALL RECORDS UPDATE At the time of her 2013 graduation, Skylar Diggins was the holder or co-holder of 32 program records and remains the only Notre Dame basketball player (male or female) to amass 2,000 points, 500 rebounds, 500 assists and 300 steals in her career. Team Single-Game Records POINTS Most Points, Half Fewest Points, Half 1. 72 (1st) at Mercer 12/30/11 1. 11 (1st) at West Virginia 1/13/08 Most Points, Game 2. 66 (1st) vs. Utah State 12/8/12 2. 12 (1st) vs. Virginia 2/22/81 1. 128 vs. Saint Francis (Pa.) 12/31/12 66 (2nd) vs. Pittsburgh 1/17/12 3. 13 (1st) vs. Villanova 3/9/03 128 at Mercer 12/30/11 4. 65 (2nd) vs. Saint Francis (Pa.) 12/31/12 4. 14 (1st) vs. Tennessee 12/31/05 3. 120 vs. Pittsburgh 1/17/12 65 (1st) vs. DePaul 12/9/15 5. 15 (1st) at St. John’s 3/3/08 4. 113 vs. Liberty 11/24/89 6. 63 (1st) vs. Saint Francis (Pa.) 12/31/12 15 (1st) at Louisville 1/14/06 5. 112 vs. Quinnipiac 11/25/14 7. 62 (2nd) vs. West Virginia 1/9/97 15 (1st) at Seton Hall 3/1/05 6. 111 vs. West Virginia 1/7/99 8. 61 (1st) vs. UMass Lowell 11/14/14 15 (1st) at Boston College 2/15/05 7. 110 at Valparaiso 11/23/15 61 (1st) vs. Syracuse 2/9/14 9. -

Named One of the Top 15 Players in WNBA History

BECKY HAMMON 1999-2014: NAMED ONE OF THE TOP 15 PLAYERS IN WNBA HISTORY Too small. Too slow. Not very athletic. In 1999, those were some deficiencies offered for why Becky Hammon’s prospects of making it to the WNBA were slim. Fifteen years later, after going from undrafted free agent to one of the league’s 15 greatest players of all-time, Hammon is retiring. She will play her final regular-season home game when the Stars take on defending league champion Minnesota at 7 p.m. today at the AT&T Center. Express-News staff writer Terrence Thomas takes a statistical look at Hammon’s career: 38 Career-high points scored in one game @ Sacramento (7-30-09) Getty Images file photo Olympics competed in. Hammon led Russia 2 to the bronze medal in 2008 in Beijing, and a fourth- place finish in 2012 in London. Estimated people it took to eat 4 the “Hammon Special,” a ham, egg and cheese sandwich the famed Carnegie Deli in New York created in her “It was a good day honor. The sandwich, for San Antonio which cost $9.95, was and a good day for made of six eggs, three slices of cheese and a few Dan Hughes. That ounces of ham. The item is no day turned out longer offered. to be a day that, I think, uplifted this franchise.” 488 1,694 DAN HUGHES, STARS Career steals, ranking Career assists, fourth COACH, ON TRADING 15th in league history in league history FOR HAMMON IN 2007 Career free-throw percentage — “Basically, what made 1,180 of 1,316 foul shots, the you have here best in WNBA history 89.7 is you have a person who has a tremendous desire to succeed because she wasn’t going to let anything prevent her from making it as a player. -

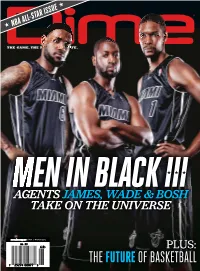

The Futureof Basketball the Futureof

π NBA ALL-STAR ISSUE π MEN IN BLACK III AGENTS JAMES, WADE & BOSH TAKE ON THE UNIVERSE www.dimemag.comMAYA / #68 / MARCHMOORE 2012 TELLS US ALL HER PLUS: SECRETS THE FUTURE OF BASKETBALL Issue #68 March 2012 www.dimemag.com Editor & Publisher Josh Gotthelf – [email protected] Director of Content Patrick Cassidy – [email protected] Managing Editor Aron Phillips – [email protected] Staff Writer Sean Sweeney – [email protected] Art Direction Alexis Cook Contributing Photographers Keith Allison David Alvarez Sid Ashford Chris Charles Tom Ciszek Joe Epstein Bob Frischmann Steven Gabriele Rebecca Goldschmidt Dorothy Hong Brian Jenkins Gary Land Troy Paraiso Paul Savramis Brandon Smith 62 Miami Contributing Writers Michael Aufses Austin L. Burton Heat Julian Caldwell Alejandro Danois Andrew Greif Bryan Horowitz Jack Jensen Martin Kessler Daniel Marks Dylan Murphy Eric Newman Lucas Shapiro Dime Interns Ryan Imparato, Kevin Smith Dime NY Office 212.629.5066 Worldwide Newsstand Distributor Curtis Circulation Company, LLC. Newsstand Consultant Howard White & Associates DIME®, THE GAME. THE PLAYER. THE LIFE.® and THE BASKETBALL LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE® are registered trademarks of Dime Magazine Publishing Company, Inc. For new subscriptions, subscription problems and/or address changes please go to www.dimemag.com, call 818.286.3153 or e-mail [email protected] PRINTED IN THE USA 8 Photo. David Alvarez Does anyone else find it strange that the hottest months for our favorites to win the NBA championship in 2012. From there, basketball take place during the coldest months in America? All- we feature three of the NBA’s rising stars – Landry Fields, DeMar Star Weekend. -

2020-21 Middle Tennessee Women's Basketball

2020-21 MIDDLE TENNESSEE WOMEN’S BASKETBALL Tony Stinnett • Associate Athletic Communciations Director • 1500 Greenland Drive, Murfreesboro, TN 37132 • O: (615) 898-5270 • C: (615) 631-9521 • [email protected] 2020-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS GAME 22: MIDDLE TENNESSEE VS. LA TECH/MARSHALL Thursday, March 11 , 2021 // 2:00 PM // Frisco, Texas OVERALL: 14-7 C-USA: 12-4 GAME INFORMATION THE TREND HOME: 8-5 AWAY: 6-2 NEUTRAL: 0-0 Venue: Ford Center at The Star (12,000) Location: Frisco, Texas NOVEMBER Tip-Off Time: 2:00 PM 25 No. 5 Louisville Cancelled Radio: WGNS 100.5 FM, 101.9 FM; 1450-AM Talent: Dick Palmer (pxp) 29 Vanderbilt Cancelled Television: Stadium Talent: Chris Vosters (pxp) DECEMBER John Giannini (analyst) 6 Belmont L, 64-70 Live Stats: GoBlueRaiders.com ANASTASIA HAYES is the Conference USA Player of the 9 Tulane L, 78-81 Twitter Updates: @MT_WBB Year. 13 at TCU L, 77-83 THE BREAKDOWN 17 Troy W, 92-76 20 Lipscomb W, 84-64 JANUARY 1 Florida Atlantic* W, 84-64 2 Florida Atlantic* W, 66-64 8 at FIU* W, 69-65 9 at FIU* W, 99-89 LADY RAIDERS (14-7) C-USA CHAMPIONSHIP 15 Southern Miss* W, 78-58 Location: Murfreesboro, Tenn. Location: Frisco, Texas 16 Southern Miss* L, 61-69 Enrollment: 21,720 Venue: Ford Center at The Star 22 at WKU* (ESPN+) W, 75-65 President: Dr. Sidney A. McPhee C-USA Championship Record: 10-4 Director of Athletics: Chris Massaro All-Time Conf. Tourn. Record: 61-23 23 at WKU* (ESPN+) W, 77-60 SWA: Diane Turnham Tourn. -

USA Vs. Oregon State

USA WOMEN’S NATIONAL TEAM • 2019 FALL TOUR USA vs. Oregon State NOV. 3, 2019 | GILL COLISEUM | 7 PM PST | PAC-12 NETWORKS PROBABLE STARTERS 2019-20 SCHEDULE/RESULTS (7-0) NO NAME PPG RPG APG CAPS 2019 FIBA AMERICUP (6-0) 5 Seimone Augustus 10.8 1.8 2.6 105 6 Sue Bird 10.1 1.7 7.1 140 9/22 USA 110, Paraguay 31 13 Sylvia Fowles 13.6 8.9 1.5 73 9/24 USA 88, Colombia 46 16 Nneka Ogwumike 16.1 8.8 1.8 48 9/25 USA 100, Argentina 50 12 Diana Taurasi 20.7 3.5 5.3 132 9/26 USA 89, Brazil 73 9/28 USA 78, Puerto Rico 54 9/29 USA 67, Canada 46 RESERVES 2019 FALL TOUR (1-0) NO NAME PPG RPG APG CAPS 23 Layshia Clarendon 4.8 1.8 2.2 21 11/2 USA 95, No. 3 Stanford 80 Pac-12 Networks 24 Napheesa Collier 13.1 6.6 2.6 40* 11/4 Oregon State (7/6)7 pm Pac-12 Networks 17 Skylar Diggins-Smith 17.9 3.3 6.2 38* 11/7 Texas A&M (6/7) 7 pm TBA 35 Allisha Gray 10.6 4.1 2.3 3 11/9 Oregon (1/1) 4 pm Pac-12 Networks 18 Chelsea Gray 14.5 3.8 5.9 0 2019 FIBA AMERICAS PRE-OLYMPIC 9 A’ja Wilson 16.5 6.4 1.8 39 QUALIFYING TOURNAMENT NOTES: 11/14 USA vs. Brazil Bahía Blanca, ARG • Stats listed for most athletes are from the 2019 WNBA 11/16 USA vs. -

Investigating the Predictive Relationship Between Sportsmanship

INVESTIGATING THE PREDICTIVE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SPORTSMANSHIP AND CLASS, AGE, TYPE OF SPORT, AND GENDER AT THE UNITED STATES MILITARY ACADEMY by Daniel J. Furlong Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University 2021 2 INVESTIGATING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SPORTSMANSHIP AND CLASS, AGE, TYPE OF SPORT, AND GENDER, AT THE UNITED STATES MILITARY ACADEMY By Daniel J. Furlong A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA 2021 APPROVED BY: Ellen Lowrie Black, Ed.D., Committee Chair Kurt Y. Michael, Ph. D., Committee Member 3 ABSTRACT Traditionally, military leaders accentuate military skill development over developing the moral character of soldiers. However, researchers have made recommendations to investigate components of sportsmanship with the intent to align better with the goals of other development programs that seek to promote character. The purpose of this quantitative, correlational design study was to use a multiple linear regression on an archival data set of Character in Sport Index scores to determine if the linear combination of the variables class, age, type of sport, and gender have predictive significance for Character in Sport Index scores. Subjects included 8,701 cadets between the ages of 17 and 27 years old attending the United States Military Academy (USMA) during the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 academic years. The findings found that the variables class, age, gender, and type of sport play a statistically significant predictive role in terms of Character in Sport Index scores. Therefore, future discussion may be justified as to investigating other avenues involved in sports education to accomplish assessing traditional institutional methods of character development to identify stronger predictive variables. -

Reps. Cheeks, Pastor, Voorhees, Bieda, Brandenburg, Condino

Reps. Cheeks, Pastor, Voorhees, Bieda, Brandenburg, Condino, Dennis, Farrah, Richardville, Sak, Spade, Waters, Emmons, Hager, Hopgood, Kolb, Kooiman, Law, Murphy, O'Neil, Stahl, Stallworth, Tobocman, Wojno, Adamini, Anderson, Brown, Caswell, Caul, Daniels, DeRossett, Elkins, Farhat, Gieleghem, Gillard, Jamnick, Julian, Lipsey, Nitz, Paletko, Reeves, Rivet, Sheltrown, Shulman, Smith, Woodward and Zelenko offered the following resolution: House Resolution No. 121. A resolution honoring the Detroit Shock Basketball Team and Head Coach Bill Laimbeer upon winning their first Women’s National Basketball Association Championship. Whereas, With no starting players older than 28 and no player older than 29, the Detroit Shock are now among the WNBA elite as they defeated their rivals the New York Liberty and the Charlotte Sting to win the Eastern Conference Championship. The Shock became the first Eastern Conference team to finish the regular season with the best overall record and the first Eastern Conference team to win the title. Their play was based on teamwork, citizenship, dedication and unselfishness. The Shock set a league record with a 16-victory improvement over 2002; and Whereas, A WNBA record-crowd of more than 22,000 saw the Shock defeat the two- time defending champion Los Angeles Sparks by a score of 83-78 in the third and final game of the finals at the Palace of Auburn Hills. This accomplishment was the first time in professional sports a team won the title after having the worst record in the league the previous season; and Whereas, Detroit Shock Head Coach Bill Laimbeer was voted WNBA's Coach of the Year. He led the Shock to a league-best 25-9 record this season and worked tirelessly to instill energy and enthusiasm in the team; and Whereas, Shock forward Cheryl Ford was selected WNBA Rookie of the Year. -

Numbers Game

THIS DAY IN SPORTS 1986 — Edmonton’s Wayne Gretzky breaks his own NHL UMBERS AME single-season points record with three assists to increase N G his total to 214. He scored 212 points in 1981-82. Antelope Valley Press, Saturday, April 4, 2020 C3 Morning rush WNBA postpones start of the season this month Valley Press news services By DOUG FEINBERG period.” PUSHED BACK U.S. Women’s Open in Houston Associated Press In this Sept. 29 Engelbert said that whenev- postponed until December NEW YORK — The WNBA photo, WNBA er the WNBA does start, it will The U.S. Women’s Open in Houston is now sched- season will not start on time Commissioner Cathy follow a strict protocol regard- uled for two weeks before Christmas. The LPGA Tour next month because of the Engelbert speaks at ing the health and well-being of pushed back the resumption of its schedule until the coronavirus pandemic, and a news conference players, coaches and fans. middle of June and found slots for three tournaments before Game 1 of that have been postponed. when it begins is unclear. basketball’s WNBA Two WNBA cities are ma- Commissioner Mike Whan keeps looking at the The league announced Fri- Finals between the jor hot spots for the virus: New calendar at a dwindling number of dates and trying to day it will delay the season for Connecticut Sun York and Seattle. One of the the figure out how it will fall into place, missing one key an indefinite period. Training and the Washington Storm’s homes for the season, piece of information brought on by the spread of the camps were to open on April 26 Mystics, in the Angel of the Winds Arena, Washington. -

The Preliminary Rounds

The Preliminary Rounds Regional Appearances and Leaders .... 28 Regional Game Records ............................ 29 First- and Second-Round Game Records ........................................... 32 Regional All-Tournament Teams ........... 36 Regional History ........................................... 39 Regional Participants ................................. 42 Stanford’s Jayne Appel 28 ALL-TIME REGIONAL APPEARANCES All-Time Regional Appearances Total Regionals (90 TEAMS) TEAM (Years in Regionals) Regionals Won Total Regionals Providence (1990) ................................................................................... 1 0 TEAM (Years in Regionals) Regionals Won Purdue (1990-92-94-95-98-99-2001-03-04-06-07-09) ............ 12 3 Alabama (1984-94-95-96-97-98) ...................................................... 6 1 Rutgers (1986-87-88-98-99-2000-05-06-07-08-09) .................. 11 2 UAB (2000) ................................................................................................. 1 0 San Diego St. (1984-85-10) ................................................................. 3 0 Arizona (1998) .......................................................................................... 1 0 San Francisco (1996) .............................................................................. 1 0 Arizona St. (1982-83-2005-07-09) .................................................... 5 0 Arkansas (1990-91-98) .......................................................................... 3 1 Seton Hall (1994) .................................................................................... -

2003 NCAA Women's Basketball Records Book

AwWin_WB02 10/31/02 4:47 PM Page 99 Award Winners All-American Selections ................................... 100 Annual Awards ............................................... 103 Division I First-Team All-Americans by Team..... 106 Divisions II and III First-Team All-Americans by Team ....................................................... 108 First-Team Academic All-Americans by Team.... 110 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners by Team ....................................................... 112 AwWin_WB02 10/31/02 4:47 PM Page 100 100 ALL-AMERICAN SELECTIONS All-American Selections Annette Smith, Texas; Marilyn Stephens, Temple; Joyce Division II: Jennifer DiMaggio, Pace; Jackie Dolberry, Kodak Walker, LSU. Hampton; Cathy Gooden, Cal Poly Pomona; Jill Halapin, Division II: Carla Eades, Central Mo. St.; Francine Pitt.-Johnstown; Joy Jeter, New Haven; Mary Naughton, Note: First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Women’s Perry, Quinnipiac; Stacey Cunningham, Shippensburg; Stonehill; Julie Wells, Northern Ky.; Vanessa Wells, West Basketball Coaches Association. Claudia Schleyer, Abilene Christian; Lorena Legarde, Port- Tex. A&M; Shannon Williams, Valdosta St.; Tammy Wil- son, Central Mo. St. 1975 land; Janice Washington, Valdosta St.; Donna Burks, Carolyn Bush, Wayland Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Dayton; Beth Couture, Erskine; Candy Crosby, Northeast Division III: Jessica Beachy, Concordia-M’head; Catie Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Harris, Ill.; Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Okla. Cleary, Pine Manor; Lesa Dennis, Emmanuel (Mass.); Delta St.; Jan Irby, William Penn; Ann Meyers, UCLA; Division III: Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Kaye Cross, Kimm Lacken, Col. of New Jersey; Louise MacDonald, St. Brenda Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Debbie Oing, Indiana; Colby; Sallie Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Elizabethtown; John Fisher; Linda Mason, Rust; Patti McCrudden, New Sue Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. St.; Susan Yow, Elon.