1 October 9, 2018 Dilek Barlas Executive Secretary, the Inspection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Avinash Kumar At/PO – Karandih Main Road, Near

CURRICULUM VITAE Avinash Kumar At/P.O. – Karandih Main Road, Near Tudu Complex, P.S. - Parsudih, Jamshedpur, East Singhbhum, Jharkhand – 831002 Mobile No. +918987589439 Email ID : [email protected] ADHAR CARD NO- 252781528309 Career Objective To acquire position in an Organization where I can make the best use of my knowledge, experience and technical skills to the maximum extent as well as undertake unending challenges with commitment to accomplish and succeed. Affix EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION Photo A) Academic :- Exam Passed Board/Univ. Name of School Year of Passing % of Marks S. S. High School, Matriculation J.S.E.B. Ranchi 2005 44% Gamaria, Jamshedpur B) Technical :- Exam Passed Board/Univ. Name of School Year of Passing % of Marks Diploma S. B. T. E. Govt. Polytechnic, Mechanical 2009 76% Jharkhand Adityapur, Jamshedpur Engineering C) Vocational Training :- Name of Organization Duration Electric Loco Shed, S. E. Railway, Tatanagar 4 Week D) Extra Qualification Name of Course Name of Institution AUTO CAD Smart Bit Computer, Pune – 411014 CAD/CAM NTTF at R. D. TATA Technical Education Centre, Jsr – 831001 VMC Operation & Programming HI-TECH COLLEGE OF CNC TECHNOLOGY, PUNE- 411019 PREVIOUS WORK :- Company Name : Carraro India Ltd ( Gear Plant ) Ranjangaon Midc Pune. Designation : Team Member (M/C Shop Division, Production, Department ) (On-Roll) EMPLOYEE I.D :- AK1029 Duration : 18 October, 2011 to 10 FAB 2017. Job Responsibilities and Achievement : 1) Working knowledge of 5s, TPM, 7QC etc. 2) Working knowledge of manufacturing processes, procedure & Machinery. 3) Working knowledge in Hobbing M/C, shaping M/C, Shaving M/C, Roofing M/C and Chamfering M/C. -

Annual Report 2009-2010

Annual Report 2009-2010 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA FARIDABAD CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD Ministry of Water Resources Govt. of India ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 FARIDABAD ANNUAL REPORT 2009 - 2010 CONTENTS Sl. CHAPTERS Page No. No. Executive Summary I - VI 1. Introduction 1 - 4 2. Ground Water Management Studies 5 - 51 3. Ground Water Exploration 52 - 78 4. Development and Testing of Exploratory Wells 79 5. Taking Over of Wells by States 80 - 81 6. Water Supply Investigations 82 - 83 7. Hydrological and Hydrometereological Studies 84 - 92 8. Ground Water Level Scenario 93 - 99 (Monitoring of Ground Water Observation Wells) 9. Geophysical Studies 100- 122 10. Hydrochemical Studies 123 - 132 11. High Yielding Wells Drilled 133 - 136 12. Hydrology Project 137 13. Studies on Artificial Recharge of Ground Water 138 - 140 14. Mathematical Modeling Studies 141 - 151 15. Central Ground Water Authority 152 16. Ground Water Studies in Drought Prone Areas 153 - 154 17. Ground Water Studies in Tribal Areas 155 18. Estimation of Ground Water Resources 156 - 158 based on GEC-1997 Methodology 19. Technical Examination of Major/Medium Irrigation Schemes 159 Sl. CHAPTERS Page No. No. 20. Remote Sensing Studies 160 - 161 21. Human Resource Development 162 - 163 22. Special Studies 164 - 170 23. Technical Documentation and Publication 171 - 173 24. Visits by secretary, Chairman CGWB , delegations and important meetings 174 - 179 25. Construction/Acquisition of Office Buildings 180 26. Dissemination and Sharing of technical know-how (Participation in Seminars, 181 - 198 Symposia and Workshops) 27. Research and Development Studies/Schemes 199 28. -

District Administration, East Singhbhum

DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION, EAST SINGHBHUM HOME DELIVERY SYSTEM DURING LOCK DOWN PERIOD >kj[k.M ljdkj List of Medical Stores in Jamshedpur-II Only order throughWhatsapp/ Normal Messages Name of Shop Mob.No. / Watsup No. 6206626110 9334048628 M/S Laxmi Medicals 9934563114 9934563114 Dimna Road, Mango 8434666903 8434666903 M/S Balajee Medicals Shop No-5B & 6B, Skyline Tower 7541064909 6201093897 Old Purulia Road, Mango M/S Medico Jawaharnagar, Main Road, 9031757535 9031757535 Azadnagar, Mango 9934543626 9934543626 M/S Bihar Medical Store 8340290813 8340290813 Main Road, Bahragora 6207473225 6207473225 M/S Puja Medicals 9835777777 9835777777 Purani Bazar, Main Road, Chakulia M/S New Drug Land 9835527063 9835527063 MANGO Main Road, Ghatsila M/S Jayshree Medical Hall 9199827905 9199827905 Block Road, Dhalbhumgarh M/S Bijay Medical Store 9955374628 9608251001 Main Road, Beltand, Patamda M/S Mahamaya Medical Hall Boram, Patamda Road, 9955126434 9955126434 Boram M/S Mahabir Medical 9955466040 9955466040 Kan Link for Home Delivery : emarket.aiwa4u.com District Administraon East Singhbhum DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION, EAST SINGHBHUM HOME DELIVERY SYSTEM DURING LOCK DOWN PERIOD >kj[k.M ljdkj List of Medical Stores in Jamshedpur-I Only order throughWhatsapp/ Normal Messages Name of Shop Mob.No. / Watsup No. M/S Modi Medical 7827172724 Kadma Market, Kadma 9709172561 M/S Shobha Medical 8210787592 Kadma Market, Kadma 7004467282 M/S Nilesh Medical 7488237553 KADMA Uliyan, Kadma 7250779646 M/S New Medical 8002102368 Kagalnagar, Sonari 7209697579 M/S Das Medical -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN NO 26. MG ROAD AND ABERDEEN BAZAR , NICOBAR PORT BLAIR -744101 704412829 704412829 ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR ,A & N ISLANDS PORT BLAIR IBKL0001498 8 7044128298 8 744259002 UPPER GROUND FLOOR, #6-5-83/1, ANIL ANIL NEW BUS STAND KUMAR KUMAR ANDHRA ROAD, BHUKTAPUR, 897889900 ANIL KUMAR 897889900 PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD ADILABAD 504001 ADILABAD IBKL0001090 1 8978899001 1 1ST FLOOR, 14- 309,SREERAM ENCLAVE,RAILWAY FEDDER ROADANANTAPURA ANDHRA NANTAPURANDHRA ANANTAPU 08554- PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTAPUR PRADESH R IBKL0000208 270244 D.NO.16-376,MARKET STREET,OPPOSITE CHURCH,DHARMAVA RAM- 091 ANDHRA 515671,ANANTAPUR DHARMAVA 949497979 PRADESH ANANTAPUR DHARMAVARAM DISTRICT RAM IBKL0001795 7 515259202 SRINIVASA SRINIVASA IDBI BANK LTD, 10- RAO RAO 43, BESIDE SURESH MYLAPALL SRINIVASA MYLAPALL MEDICALS, RAILWAY I - RAO I - ANDHRA STATION ROAD, +91967670 MYLAPALLI - +91967670 PRADESH ANANTAPUR GUNTAKAL GUNTAKAL - 515801 GUNTAKAL IBKL0001091 6655 +919676706655 6655 18-1-138, M.F.ROAD, AJACENT TO ING VYSYA BANK, HINDUPUR , ANANTAPUR DIST - 994973715 ANDHRA PIN:515 201 9/98497191 PRADESH ANANTAPUR HINDUPUR ANDHRA PRADESH HINDUPUR IBKL0001162 17 515259102 AGRICULTURE MARKET COMMITTEE, ANANTAPUR ROAD, TADIPATRI, 085582264 ANANTAPUR DIST 40 ANDHRA PIN : 515411 /903226789 PRADESH ANANTAPUR TADIPATRI ANDHRA PRADESH TADPATRI IBKL0001163 2 515259402 BUKARAYASUNDARA M MANDAL,NEAR HP GAS FILLING 91 ANDHRA STATION,ANANTHAP ANANTAPU 929710487 PRADESH ANANTAPUR VADIYAMPETA UR -

Annual Report 2018-19

FINSERVE PRIVATE LIMITED “Enduring Relationships...” ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 SAMBANDH FINSERVE PVT. LTD. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K C M Y CM MY FINSERVE PRIVATE LIMITED CY CMY “Enduring Relationships...” K CONTENT 1 Board of Directors ODISHA Sundargarh Jharsuguda Keonjhar 3 Management Team Mayurbhanj Khorda Sambalpur Deogarh Angul Balasore 9 Financial Spotlight Bhadrak Nabrangpur 13 Our Products 17 System Efficiency C M Y 19 Human Capital CM MY Chhattisgarh Raipur CY SPM & PE Raigarh CMY 21 Janjgir Bilaspur K Dhamtari Balod Occasions & Initiatives Mahasamund 27 that mattered most 32 Director’s Report 39 Annexures to Director’s Report 48 Corporate Governance Report 49 Secretarial Audit Report Jharkhand Ranchi Independent Auditor’s Report Simdega & Financials Ramgarh 52 Gumla East Singhbhum Vision Mission Sambandh envisages a Sambandh responsibly provides client socio-economically centric, inclusive financial and allied prosperous society. services to the small and marginal entrepreneurs, predominantly women to transform their livelihoods and household well-being. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Core Value Philosophy Statement To be a listening and caring partner SFPL strives for excellence in service to individuals and households in quality through innovations in their journey to financial well-being product design & simplicity in service and economic freedom. delivery, by its committed employees who give utmost respect and empathy towards the target groups while being transparent in dealing and earning trust of the stakeholders which in turn brings recognition & rewards. Social Goals Provisioning of product & Building awareness & capabilities services that will have a lasting of our clients to take informed impact on clients’ livelihood and financial and business decision. -

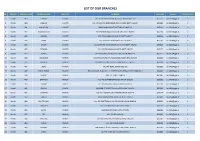

List of Our Branches

LIST OF OUR BRANCHES SR REGION BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME DISTRICT ADDRESS PIN CODE E-MAIL CONTACT NO 1 Ranchi 419 DORMA KHUNTI VILL+PO-DORMA,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI-835 227 835227 [email protected] 0 2 Ranchi 420 JAMHAR KHUNTI VILL-JAMHAR,PO-GOBINDPUR RD,VIA-KARRA DISTT-KHUNTI. 835209 [email protected] 0 3 Ranchi 421 KHUNTI (R) KHUNTI MAIN ROAD,KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI-835 210 835210 [email protected] 0 4 Ranchi 422 MARANGHADA KHUNTI VILL+PO-MARANGHADA,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI 835210 [email protected] 0 5 Ranchi 423 MURHU KHUNTI VILL+PO-MURHU,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI 835216 [email protected] 0 6 Ranchi 424 SAIKO KHUNTI VILL+PO-SAIKO,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI 835210 [email protected] 0 7 Ranchi 425 SINDRI KHUNTI VILL-SINDRI,PO-KOCHASINDRI,VIA-TAMAR,DISTT-KHUNTI 835225 [email protected] 0 8 Ranchi 426 TAPKARA KHUNTI VILL+PO-TAPKARA,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI 835227 [email protected] 0 9 Ranchi 427 TORPA KHUNTI VILL+PO-TORPA,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI-835 227 835227 [email protected] 0 10 Ranchi 444 BALALONG RANCHI VILL+PO-DAHUTOLI PO-BALALONG,VIA-DHURWA RANCHI 834004 [email protected] 0 11 Ranchi 445 BARIATU RANCHI HOUSING COLONY, BARIATU, RANCHI P.O. - R.M.C.H., 834009 [email protected] 0 12 Ranchi 446 BERO RANCHI VILL+PO-BERO, RANCHI-825 202 825202 [email protected] 0 13 Ranchi 447 BIRSA CHOWK RANCHI HAWAI NAGAR, ROAD NO. - 1, KHUNTI ROAD, BIRSA CHOWK, RANCHI - 3 834003 [email protected] 0 14 Ranchi 448 BOREYA RANCHI BOREYA, KANKE, RANCHI 834006 [email protected] 0 15 Ranchi 449 BRAMBEY RANCHI VILL+PO-BRAMBEY(MANDER),RANCHI-835205 835205 [email protected] 0 16 Ranchi 450 BUNDU -

East Singhbhum District, Jharkhand State

भजू ल सचू ना पस्ु तिका डﴂभूम जिला, झारख ﴂपूर्बी स घ Ground Water Information Booklet East Singhbhum District, Jharkhand State AUTO FLOW BORE WELL LOCATED AT VILLAGE KUDADA के न्द्रीय भूमिजल बो셍 ड Central Ground water Board जल संसाधन िंत्रालय Ministry of Water Resources (भारि सरकार) रा煍य एकक कायाडलय, रााँची (Govt. of India) िध्य-पर्वू ी क्षेत्र State Unit Office,Ranchi पटना Mid-Eastern Region Patna मसिंबर 2013 September 2013 1 भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका डﴂभूम जिला, झारख ﴂपूर्बी स घ Ground Water Information Booklet East Singhbhum District, Jharkhand State Prepared By ुनिल टोꥍपो (वैज्ञानिक ख ) Sunil Toppo (Scientist B) रा煍य एकक कायाडलय, रााँची िध्य-पूर्वी क्षेत्र,पटना State Unit Office, Ranchi Mid Eastern Region, Patna 2 GROUND WATER INFORMATION OF EAST SINGHBHUM DISTRICT, JHARKHAND STATE Contents Sr. Chapter Pages No. 1.0 Introduction 8 1.1 Introduction 8 1.2 Demography 9 1.3 Physiography and Drainage 9 1.4 Irrigation 10 1.5 Previous Studies 10 2.0 2.0 Climate and rainfall 11 3.0 3.0 Soil 11 4.0 4.0 Geology 11 5.0 Ground Water Scenario 13 5.1 Hydrogeology 13 5.1.1 Depth to water level 13 5.1.2 Seasonal fluctuation 14 5.1.3 Exploratory wells 14 5.1.4 Long term water level trend 14 5.2 Ground water resource 15 5.3 Ground Water Quality 15 5.4 Status of ground water development 15 6.0 Ground water management strategy 16 6.1 Ground water development 16 6.2 Water conservation and artificial recharge 16 7.0 Ground water related issue and problems 17 8.0 Awareness and training activity 17 8.1 The mass awareness programme (MAP) 17 8.2 Participation in exhibition, mela, fair etc. -

District Administration, East Singhbhum

DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION, EAST SINGHBHUM HOME DELIVERY SYSTEM DURING LOCK DOWN PERIOD >kj[k.M ljdkj Essential Item/Milk/Bread/Diapers/Baby Essentials Only order throughWhatsapp/ Normal Messages Name of Zone Name of Shop Contact No. Area Alloted 8709913132 ----- 7209568814 Mango, Azadnagar 9709120288 MGM, Olidih, Dimna Road 8826782002 Dimna Road, Olidih 8877360835 Mango, Azadnagar ZONE NO: 1 8092531344 Dimna Road, Olidih MANGO 8340569670 Mango, Azadnagar 9334727785 8928932040 Mango, Azadnagar, MGM In case of any difficulty please contact following person Name of Supervising Name of VLE Contact No. Contact No. Officer Sri Rahul Tiwary 7209737779 Sri Pradeep Kumar, 7004956229 Sri Rajesh Kumar Saw 9234764410 Sr. Rollout Manager, NIC, Jamshedpur Link for Home Delivery : emarket.aiwa4u.com District Administraon East Singhbhum DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION, EAST SINGHBHUM HOME DELIVERY SYSTEM DURING LOCK DOWN PERIOD >kj[k.M ljdkj Essential Item/Milk/Bread/Diapers/Baby Essentials Only order throughWhatsapp/ Normal Messages Name of Zone Name of Shop Contact No. Area Alloted 8404974578 9955813228 All Area (Kadma Police Station) Shree Durga Store 9472727676 C.H.Area, Northern Town, B.H.Area, Dhatkidih 9934174811 Dhatkidih, State Mile Road, Kadma Market, Uliyan, Bajrang Store 9835196466 Bhaa Bas Arjun Store 9835171755 Kadma Uliyan, B.H.Area, Shastri Nagar, 7992233838 ECC Flat, Ramjanam Nagar ZONE NO: 2 KADMA Kadma Uliyan, B.H.Area, Ramdas Bhaa, 7004402231 Near Rankini Mandir, Kadma Uliyan, Vijaya Heritage 8657658023 All Area (Kadma Police Staon) Suvidha Store -

Bokaro Bank of India 94307 56045

Land Line Number / Mobile Number Of Name of Bank / Branch to impart ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name Of Bank Controlling Heads of Mapping Banks in Financial Literacy to the Students of ITI s Jharkhand State 0651-236 1530 , 236 1531 , 97099 99878 PR20000026 Television & Video Training Institute (PVT ITI) P Kisori Niwas Gujarat Colony, PO-Chas Bokaro Jharkhand Bokaro [email protected] Indian Overseas Bank - Chas Branch Indian Overseas Bank 0612-238 5476 / 75418 08701 [email protected] PR20000027 Birsa Vikash Industrial Training Centre P By pass Road Near Garga Bridge, Chas Bokaro Jharkhand Bokaro m Dena Bank - Chas Branch Dena Bank 0651- 233 1073/ 6450 222 / 97714 PR20000062 J.P.S Memorial Industrial Training Centre Balidih P Balidih Jharkhand Bokaro NULL Punjab National Bank - Chas Branch Punjab National Bank 96055 PR20000088 Asha PVT ITI P Solagidih Chass Jharkhand Bokaro NULL Bank of Baroda - Chas Branch Bank of Baroda 0657- 224 9391 / 75420 32132 PR20000121 Vinoba Bhave PVT ITI P More, Chas Jharkhand Bokaro NULL Andhra Bank - Chas Branch Andhra Bank 0612- 232 3147 / 99341 23546 PR20000122 Siddhu Kanhu PVT ITI P Labudih, Chas Jharkhand Bokaro NULL Allahabad Bank - Chas Branch Allahabad Bank 0651- 256 3114 / 94311 45678 PR20000123 Bokaro PVT ITI P CISF Campus, Bokaro Steel City Jharkhand Bokaro NULL Canara Bank - Sector IV Branch Canara Bank 0651 2331752 / 233 1850 / 99343 63088 Jharkhand Gramin Bank - PR20000124 Dr. B.R. Ambedkar PVT ITI P Chandankiyari Jharkhand Bokaro NULL Chandankiyari Branch Jharkhand Gramin Bank 0651 2202 120 / 2330 338 / 75418 13901 PR20000135 National Private ITI P At +Po. -

State District City Address Type Jharkhand Bokaro

STATE DISTRICT CITY ADDRESS TYPE AXIS BANK ATM, KHATA NO.211 POLO NO. 1445 MOZA NO. 28 JHARKHAND BOKARO BOKARO THANA NO 108, AGARWAL MEDICINE STORE, BANK MORE CHOWK, OFFSITE GOMIA BOKARO JHARKHAND. 829111. AXIS BANK ATM, MAIN ROAD CHAS, P.O+P.S- CHAS, DIST- BOKARO, JHARKHAND BOKARO BOKARO OFFSITE JHARKHAND - 827013 AXIS BANK ATM, MAIN ROAD CHAS NEAR PETROL PUMP,PO- JHARKHAND BOKARO BOKARO OFFSITE CHAS,DIST-BOKARO,PIN-827013, JHARKHAND AXIS BANK LTD, GROUND FLOOR , THE RAJDOOT HOTEL, NEAR JHARKHAND BOKARO BOKARO K.M.MEMORIAL HOSPITAL,BYE PASS ROAD, CHAS – ONSITE BOKARO,JHARKHAND,PIN CODE: 827013. AXIS BANK LTD, GROUND FLOOR , NEAR HOTEL URVARSHI, MAIN JHARKHAND BOKARO BOKARO ONSITE ROAD PHUSRO BAZAR, JHARKHAND. 829144 AXIS BANK ATM CENTRE MARKET SECTOR 9 PLOT NO C2 BOKARO JHARKHAND BOKARO BOKARO OFFSITE STEEL CITY BOKARO JHARKHAND 827009 AXIS BANK LTD OPPOSITE KALI MANDIR POST OFFICE MORE PO JHARKHAND BOKARO BOKARO ONSITE GOMIA DIST BOKARO JHARKHAND 829111 AXIS BANK ATM KHATA NO 350 PLOT NO 4709 RAKWA 38 DISMIL JHARKHAND BOKARO BOKARO THANA NO 123 MOUJA HOSIR MAIN ROAD SADAM PO HOSIR PS OFFSITE GOMIA DIST BOKARO JHARKHAND 829111 AXIS BANK ATM, HOLDING NO:-148, WARD NO:-17, P.O:-CHATRA, JHARKHAND CHATRA CHATRA P.S:-CHATRA, NEAR OLD PETROL PUMP , MAIN ROAD CHATRA, DIST:- OFFSITE CHATRA, JHARKHAND, PIN-825401 AXIS BANK ATM, KHATA NO:- 117, PLOT NO:- 574, WARD NO;-21, HOLDING NO:- 156A OLD/ 05 NEW, RAKWA:- 2.75 DISMIL, THANA JHARKHAND CHATRA CHATRA NO:- 005, HALKA- 6B, MOUZA:- NAGWA, ANCHAL:- CHATRA, OPP. DC OFFSITE OFFICE NEAR COLLEGE ROAD CHATRA, DIST- CHATRA, JHARKHAND, PIN-825401 AXIS BANK LTD, GROUND & FIRST FLOOR MAIN ROAD PO & PS JHARKHAND CHATRA CHATRA ONSITE CHATRA DIST CHATRA 825401 JHARKHAND AXIS BANK ATM, CIRCULAR ROAD NEAR SATSANG CHOWK,PO- JHARKHAND DEOGHAR BELABAGAN OFFSITE BELABAGAN,DIST-DEOGHAR, 814112 AXIS BANK ATM, AT: ECL, CHITRA, OPP. -

KARIM CITY COLLEGE, TEACHING FACULTY of ( B.Ed.)

KARIM CITY COLLEGE, TEACHING FACULTY OF ( B.Ed.) Sl.No. Name of the Father’s Address Category Contact Qualification Perc Experience Date of Date of Reasons of Bank A/c No. Details Appointment Remarks Staff Name (Gen/SC/S No./Mob.No. enta Joining Resign Resignation of against whom if any T/OBC/Oth ge. of the staff Salary ers) 1. Dr. Sucheta NIL E-2/1, Gangotri Complex, M.Com., M.Ed., 66.88 21 years Bhuyan P.C. Samal ST 9204629110 12/07/2000 NIL 07631000010716 38,127 Baradwari, Sakchi Ph.D. (Education) % 2. NET (Education), NIL NIL Dr. Sandhya A/IV/11, NML Flats, Agrico, NET (Hindi), Ph.D N.P. Singh Gen 9835345653 67% 13.5 years 16/09/2005 07631000010581 36,878 Sinha Jsr (Geography) & Ph.D (Hindi) 3. M.A. (Economics NIL NIL M.T.M. Hospital Stocking Prof. Parween Lt. S.A. and History), Rd, “N” Town Jamshedpur, Gen 9661479949 50% 16 years 16/09/2005 07631000010582 36,878 Usmani Usmani M.ED 831001 4. Professors’ Colony, Near NIL NIL Mrs. Nusrat Iqbal Ahmad J.K.S. College, Rd No.18, Gen 8969813379 Msc (Zoology), M.Ed.74% 6 years 07/09/2012 07631000016191 30,313 Begum Azadnagar 5. 143, Rahman Cottage, Rd. NIL NIL Prof. Shibanur Hasibur M.A., M.Ed. No. 17A/3, Green Valley, Gen 9304059857 64.41 5 years 18/08/2012 07631000016191 30,313 Rahman Rahman Zakirnagar, Jsr % 6. M.Sc. NIL NIL Hifzur Prof. Samiullah Garhara, Begusarai, Bihar Gen 8986143200 (Mathematics), 69% 5 years 05/08/2014 07631000018824 28,438 Rahman M.Ed. -

Blockwise Schools with Number of Teachers and Total Enrolment

BLOCKWISE SCHOOLS WITH NUMBER OF TEACHERS AND TOTAL ENROLMENT Total Total Block Sch Code School Name Sch Category Cluster Village enrolment teacher BAHRAGORA 0700102 P.S.CHINGRA BANGLA, B2 Primary M.S.GANDANATA, B2 CHINGRA 33 2 BAHRAGORA 0700103 UPGRADED M.S.CHINGRA HINDI,B2 Primary with Upper Primary M.S.KATUSHOL, B2 CHINGRA 243 6 BAHRAGORA 0700301 UPGRADED PS DUMURIA Primary M.S.KATUSHOL, B2 DUMARIA 33 2 BAHRAGORA 0700501 P.S.DAKSHINASHOL, B-2 Primary M.S.KATUSHOL, B2 DAKSHINASHOL 67 2 BAHRAGORA 0700601 BHANDARSHOL UTKRAMIT M.S. Primary with Upper Primary M.S.KATUSHOL, B2 BHANDARSHOL 154 3 BAHRAGORA 0701001 UPG GOVT M.S.KADOKOTHA, B-2 Primary with Upper Primary M.S.KATUSHOL, B2 KADOKOTHA 113 4 BAHRAGORA 0701101 DPEP N.P.S.DHILAHARA Primary M.S.GANDANATA, B2 DHILAHARA 33 2 BAHRAGORA 0701301 M.S.BANKATA (OU) Primary with Upper Primary M.S.BENDAMOUDA, B1 BANKATA 281 5 BAHRAGORA 0701302 UPGRADED PS BANKATIYA Primary M.S.GOPALPUR, B1 BANKATA 22 2 BAHRAGORA 0701501 P.S.GAURISHOL, B-2 Primary M.S.GANDANATA, B2 GAURISHOL 52 1 BAHRAGORA 0701601 UPG GOVT M.S.NAKDOHA, B-2 Primary with Upper Primary M.S.GANDANATA, B2 NAKDOHA 100 5 BAHRAGORA 0701701 P.S.PANKHISHOL, B-2 Primary M.S.GANDANATA, B2 PANKHISHOL 31 1 BAHRAGORA 0701702 UPGRADED PS PANISHOL Primary M.S.LODHANBANI, B1 PANKHISHOL 17 2 BAHRAGORA 0701801 M.S.GANDANATA Primary with Upper Primary M.S.GANDANATA, B2 GANDANATA 131 5 BAHRAGORA 0701802 P.S.GANDANATA Primary M.S.GANDANATA, B2 GANDANATA 32 1 BAHRAGORA 0701902 P.S.BENASHOLI, B-2 Primary M.S.MANUSH MURIYA, B2 BENASHOLI 22 2 BAHRAGORA 0701903 UPGRADED MS BENASHOLI Primary with Upper Primary M.S.LODHANBANI, B1 BENASHOLI 79 3 BAHRAGORA 0701904 UPGRADED PS SITUMDIHI Primary M.S.JHANJHIYA, B1 BENASHOLI 25 2 BAHRAGORA 0702001 UPGRADED GOVT H.S.KATUSHOL, B-2 Pr.