Yanko Dissertation 2021 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Songs by Artist

DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist Title Versions Title Versions ! 112 Alan Jackson Life Keeps Bringin' Me Down Cupid Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Dance With Me Do Its Over Now +44 Peaches & Cream When Your Heart Stops Beating Right Here For You 1 Block Radius U Already Know You Got Me 112 Ft Ludacris 1 Fine Day Hot & Wet For The 1st Time 112 Ft Super Cat 1 Flew South Na Na Na My Kind Of Beautiful 12 Gauge 1 Night Only Dunkie Butt Just For Tonight 12 Stones 1 Republic Crash Mercy We Are One Say (All I Need) 18 Visions Stop & Stare Victim 1 True Voice 1910 Fruitgum Co After Your Gone Simon Says Sacred Trust 1927 1 Way Compulsory Hero Cutie Pie If I Could 1 Way Ride Thats When I Think Of You Painted Perfect 1975 10 000 Maniacs Chocol - Because The Night Chocolate Candy Everybody Wants City Like The Weather Love Me More Than This Sound These Are Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH 10 Cc 1st Class Donna Beach Baby Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz Good Morning Judge I'm Different (Clean) Im Mandy 2 Chainz & Pharrell Im Not In Love Feds Watching (Expli Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz And Drake The Things We Do For Love No Lie (Clean) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Chainz Feat. Kanye West 10 Years Birthday Song (Explicit) Beautiful 2 Evisa Through The Iris Oh La La La Wasteland 2 Live Crew 10 Years After Do Wah Diddy Diddy Id Love To Change The World 2 Pac 101 Dalmations California Love Cruella De Vil Changes 110 Dear Mama Rapture How Do You Want It 112 So Many Tears Song List Generator® Printed 2018-03-04 Page 1 of 442 Licensed to Lz0 DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist -

Bush Pdf Free Download

BUSH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jean Edward Smith | 832 pages | 08 Sep 2016 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781476741192 | English | New York, United States Bush | Definition of Bush by Merriam-Webster Keep scrolling for more More Definitions for bush bush. Please tell us where you read or heard it including the quote, if possible. Test Your Knowledge - and learn some interesting things along the way. Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free! Whereas 'coronary' is no so much Put It in the 'Frunk' You can never have too much storage. What Does 'Eighty-Six' Mean? We're intent on clearing it up 'Nip it in the butt' or 'Nip it in the bud'? We're gonna stop you right there Literally How to use a word that literally drives some pe Is Singular 'They' a Better Choice? Name that government! Or something like that. Can you spell these 10 commonly misspelled words? Do you know the person or title these quotes desc Login or Register. Save Word. Bush biographical name 1. Bush biographical name 2. Bush biographical name 3. First Known Use of bush Noun 1 14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1a Verb 15th century, in the meaning defined at transitive sense Adjective 1 , in the meaning defined at sense 1 Noun 2 , in the meaning defined above Adjective 2 , in the meaning defined above. Keep scrolling for more. The episode included an interview with program host, Nic Harcourt. They toured with Nickelback on their Here and Now Tour. On 26 March , it was reported that Bush had begun recording their sixth studio album with producer Nick Raskulinecz. -

Alternative 2020

Mediabase Charts Alternative 2020 Published (U.S.) -- Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 Rank Artist Title 1 TWENTY ONE PILOTS Level Of Concern 2 BILLIE EILISH everything i wanted 3 AJR Bang! 4 TAME IMPALA Lost In Yesterday 5 MATT MAESON Hallucinogenics 6 ALL TIME LOW Monsters f/blackbear 7 ABSOFACTO Dissolve 8 POWFU Coffee For Your Head 9 SHAED Trampoline 10 UNLIKELY CANDIDATES Novocaine 11 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Black Madonna 12 MACHINE GUN KELLY Bloody Valentine 13 STROKES Bad Decisions 14 MEG MYERS Running Up That Hill 15 HEAD AND THE HEART Honeybee 16 PANIC! AT THE DISCO High Hopes 17 KILLERS Caution 18 WEEZER Hero 19 TWENTY ONE PILOTS The Hype 20 WALLOWS Are You Bored Yet? 21 LOVELYTHEBAND Broken 22 DAYGLOW Can I Call You Tonight? 23 GROUPLOVE Deleter 24 SUB URBAN Cradles 25 NEON TREES Used To Like 26 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Social Cues 27 WHITE REAPER Might Be Right 28 BLACK KEYS Shine A Little Light 29 LUMINEERS Life In The City 30 LANA DEL REY Doin' Time 31 GREEN DAY Oh Yeah! 32 MARSHMELLO Happier f/Bastille 33 AWOLNATION The Best 34 LOVELYTHEBAND Loneliness For Love 35 KENNYHOOPLA How Will I Rest In Peace If... 36 BAKAR Hell N Back 37 BLUE OCTOBER Oh My My 38 KILLERS My Own Soul's Warning 39 GLASS ANIMALS Your Love (Deja Vu) 40 BILLIE EILISH bad guy 41 MATT MAESON Cringe 42 MAJOR LAZER F/MARCUS Lay Your Head On Me 43 PEACH TREE RASCALS Mariposa 44 IMAGINE DRAGONS Natural 45 ASHE Moral Of The Story f/Niall 46 DOMINIC FIKE 3 Nights 47 I DONT KNOW HOW BUT THEY.. -

Roxbox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat

RoxBox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Bartender Jucxi D Blackout Careless Whisper Other Side 2 Unlimited 10 Years No Limit Actions & Motives 20 Fingers Beautiful Short Dick Man Drug Of Choice 21 Demands Fix Me Give Me A Minute Fix Me (Acoustic) 2Pac Shoot It Out Changes Through The Iris Dear Mama Wasteland How Do You Want It 10,000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Because The Night 2Pac Feat Dr. Dre Candy Everybody Wants California Love Like The Weather 2Pac Feat. Dr Dre More Than This California Love These Are The Days 2Pac Feat. Elton John Trouble Me Ghetto Gospel 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Eminem Cruella De Vil One Day At A Time 10cc 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dreadlock Holiday Runnin' Good Morning Judge 3 Doors Down I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun The Things We Do For Love Be Like That Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 112 Citizen Soldier Dance With Me Duck & Run Peaches & Cream Every Time You Go Right Here For You Here By Me U Already Know Here Without You 112 Feat. Ludacris It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Hot & Wet Kryptonite 112 Feat. Super Cat Landing In London Na Na Na Let Me Be Myself 12 Gauge Let Me Go Dunkie Butt Live For Today 12 Stones Loser Arms Of A Stranger Road I'm On Far Away When I'm Gone Shadows When You're Young We Are One 3 Of A Kind 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Gavin Rossdale Chosen As Art Ambassador for La Art Show

Media Inquiries Heidi Johnson HIJINX Arts [email protected] 323.204.7246 GAVIN ROSSDALE CHOSEN AS ART AMBASSADOR FOR LA ART SHOW The Kick-Off Party For LA’s Longest-Running Art Fair Unites International Collectors, Artists, Celebrities and Art Patrons In the Fight to End Childhood Cancer OPENING NIGHT PREMIERE Wednesday, January 23, 2019 Red Card Collectors | 6pm - 7pm Vanguard | 7pm - 8pm Friends | 8pm - 11pm SHOW HOURS Thursday, January 24, 2019 | 11am – 7pm Friday, January 25, 2019 | 11am – 7pm Saturday, January 26, 2019 | 11am – 7pm Sunday, January 27, 2019 | 11am – 5pm LOS ANGELES CONVENTION CENTER - WEST HALL 1201 South Figueroa Street Los Angeles, CA 90015 TICKETS https://tinyurl.com/LAArtShow2019 Media Inquiries Heidi Johnson HIJINX Arts [email protected] 323.204.7246 Gavin Rossdale, lead vocalist, songwriter and guitarist for the band BUSH, has been chosen as an Art Ambassador for the 2019 LA Art Show. This year’s 24th addition will be held Jan. 24–27 at the Los Angeles Convention Center. The LA Art Show, one of the largest international art fairs in the country, attracts an elite roster of national and international galleries, acclaimed artists, highly regarded curators, architects, design professionals, along with collectors and the general public. Rossdale was tapped as art ambassador based on his history as an active art collector and a supporter of galleries in Los Angeles and around the world. He’ll appear Jan. 23rd at the 2019 Opening Night Premiere Gala, opening night event to be hosted by actor Kate Beckinsale. Proceeds from that evening will support of St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital for the fifth year in a row. -

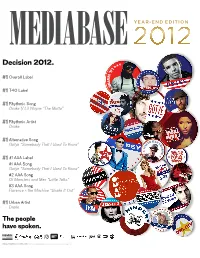

Decision 2012

YEAR-END EDITION MEDIABASE 2012 Decision 2012. #1 Overall Label #1 T40 Label #1 Rhythmic Song Drake f/ Lil Wayne “The Motto” #1 Rhythmic Artist Drake Alternative Song #1 HAW ER T Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” Y H A O M R N H E H #1 #1 AAA Label #1 AAA Song Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” #2 AAA Song Of Monsters and Men “Little Talks” #3 AAA Song Florence + the Machine “Shake It Out” #1 Urban Artist Drake The people have spoken. www.republicrecords.com c 2012 Universal Republic Records, a Division of UMG Recordings, Inc. REPUBLIC LANDS TOP SPOT OVERALL Republic Top 40 Champ Island Def Jam Takes Rhythmic & Urban Republic t o o k t h e t o p s p o t f o r t h e 2 0 1 2 c h a r t y e a r, w h i c h w e n t f r o m N o v e m b e r 2 0 , 2 0 1 1 - N o v e m b e r 17, 2012. The label was also #1 at Top 40 and Triple A, while finishing #2 at Rhythmic, #3 at Urban, and #4 at AC. Their overall share was 13.5%. Leading the way for Republic was newcomer Gotye, who had one of the year’s biggest hits with “Somebody That I Used To Know.” A big year from Drake and Nicki Minaj also contributed to the label’s success, as well as strong performances for Florence + The Machine, Volbeat, and Of Monsters And Men to name a few. -

Rock Chart Wire: Week of December 17Th

Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com Rock Chart Wire: Week of December 17th [TABLE=131] *Note: “*” denotes a new addition to the top 5. Changes from last week’s chart: Bush holds onto the #1 spot for a fifth week in a row with “The Sound Of Winter.” The Black Keys climb one spot, landing at #2 with “Lonely Boy.” Foo Fighters drop one spot, landing at #3 with “Walk.” Coldplay holds onto the #4 spot for a second week in a row with “Paradise.” Seether drops out of the top 5, landing at #6 with “Tonight.” Chevelle enters the top 5 at the #5 spot with “Face To The Floor.” New Arrivals To The Top 5: “Face To The Floor” (Chevelle – Rock): Written Pete Loeffler, Sam Loeffler and Dean Bernardini, “Face To The Floor” was the first single release from the “Hats Off to the Bull” album and is characterized by an infectious, memorable riff that occurs in the intro, verse and chorus sections, an engaging bridge/instrumental break section that provides a strong departure from the rest of the song, and “pissed off” lyrics that reflect the damage caused by Madoff and his Ponzi scheme. Songwriter Alert: When you’ve got a strong, infectious riff like the one that defines the intro, verse and chorus sections of “Face To The Floor,” making ample use of it throughout your song is a great way to take the memorability factor of your song to the next level. Remember, though, that overuse use can start to bore the listener and ultimately cause them to lose interest. -

Artist Song Album Blue Collar Down to the Line Four Wheel Drive

Artist Song Album (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Blue Collar Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Down To The Line Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Four Wheel Drive Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Free Wheelin' Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Gimme Your Money Please Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Hey You Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Lookin' Out For #1 Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Roll On Down The Highway Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Take It Like A Man Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Hits of 1974 (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Hits of 1974 (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. Blue Sky Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Rockaria Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Showdown Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Strange Magic Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Sweet Talkin' Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Telephone Line Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Turn To Stone Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

I'll Make a Man out of You 000 Maniacs 10 More Than This 10,000

# -- -- 20 Fingers I'll Make A Man Out Of You Short #### Man 000 Maniacs 10 20th Century Boy More Than This T. Rex 10,000 Maniacs 21St Century Girls Because The Night 21St Century Girls Like The Weather More Than This 2 Chainz feat.Chris Brown These Are The Days Countdown Trouble Me Countdown (MPX) 100% Cowboy 2 Chainz ftg. Drake & Lil Wayne Meadows, Jason I Do It 101 Dalmations (Disney) 2 Chainz & Wiz Khalifa Cruella De Vil We Own It (Fast & Furious) 10cc 2 Evisa Donna Oh La La La Dreadlock Holiday I'm Mandy 2 Live Crew I'm Not In Love Rubber Bullets Do Wah Diddy Diddy The Things We Do For Love Me So Horny Things We Do For Love We Want Some P###Y Things We Do For Love, The Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pac California Love 112 California Love (Original ... Dance With Me Changes Dance With Me (Radio Version) Changes Peaches And Cream How Do You Want It Peaches And Cream (Radio ... Until The End Of Time (Radio ... Peaches & Cream Right Here For You 2 Pac & Eminem U Already Know One Day At A Time 112 & Ludacris 2 Pac & Eric Will Hot & Wet Do For Love 12 Gauge 2 Pac Featuring Dr. Dre Dunkie Butt California Love 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Pistols & Ray J. 1, 2, 3 Red Light You Know Me Simon Says You Know Me (Wvocal) 1975 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay Dizm Sincerity Is Scary She Got It TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME She Got It (Wvocal) 1975, The 2 Unlimited Chocolate No Limits 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 1 # 30 Seconds To Mars When Your Young ..