Thomas Cook/Co-Op/Midlands Joint Venture Final Report: Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016-2017

HARNESSING TECHNOLOGY FOR BETTER CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE. Annual Report 2016-2017 Registered Office: Thomas Cook (India) Limited CIN: L63040MH1978PLC020717 Thomas Cook Building, Dr. D N Road, Fort, Mumbai - 400001, India Board: +91-22-4242 7000onlonlineine bobooki| oki Fax:ng +91-22-2302 2864 online booking BOARD OF DIRECTORS Madhavan Menon, Chairman and Managing Director Harsha Raghavan, Non Executive Director Chandran Ratnaswami, Non Executive Director Kishori Udeshi, Non Executive Director – Independent Pravir Kumar Vohra, Non Executive Director – Independent Nilesh Vikamsey, Non Executive Director – Independent Sunil Mathur, Non Executive Director – Independent COMPANY SECRETARY Amit J. Parekh –Company Secretary & Compliance Officer CONTENTS AUDITORS Lovelock & Lewes Directors Report ..............................................................................01 Annexure to Directors’ Report .........................................................10 PRINCIPAL BANKERS (in alphabetical order) Axis Bank Limited Management Discussion and Analysis Report .................................35 Bank of America Report of Directors on Corporate Governance .................................45 HDFC Bank Limited ICICI Bank Limited Certificate of Compliance on Corporate Governance........................69 IDFC Bank Limited CEO/ CFO Certification and Declaration Induslnd Bank Limited Kotak Mahindra Bank Limited on Compliance of Code of Conduct ................................................70 RBL Bank Business Responsibility Report.........................................................71 -

Annual Report of the Tui Group 2019 2019 Annual Report of the Tui Group 2019 Financial Highlights

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TUI GROUP 2019 2019 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TUI GROUP THE OF REPORT ANNUAL 2019 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 2019 2018 Var. % Var. % at adjusted constant € million currency Turnover 18,928.1 18,468.7 + 2.5 + 2.7 Underlying EBITA1 Hotels & Resorts 451.5 420.0 + 7.5 – 4.9 Cruises 366.0 323.9 + 13.0 + 13.2 Destination Experiences 55.7 45.6 + 22.1 + 20.4 Holiday Experiences 873.2 789.5 + 10.6 + 3.6 Northern Region 56.8 278.2 – 79.6 – 77.1 Central Region 102.0 94.9 + 7.5 + 7.0 Western Region – 27.0 124.2 n. a. n. a. Markets & Airlines 131.8 497.3 – 73.5 – 72.2 All other segments – 111.7 – 144.0 + 22.4 + 18.5 TUI Group 893.3 1,142.8 – 21.8 – 25.6 EBITA2, 3 768.4 1,054.5 – 27.1 Underlying EBITDA3, 4 1,359.5 1,554.8 – 12.6 EBITDA3, 4 1,277.4 1,494.3 – 14.5 EBITDAR3, 4, 5 1,990.4 2,215.8 – 10.2 Net profi t for the period 531.9 774.9 – 31.4 Earnings per share3 in € 0.71 1.17 – 39.3 Equity ratio (30 Sept.)6 % 25.6 27.4 – 1.8 Net capex and investments (30 Sept.) 1,118.5 827.0 + 35.2 Net debt / net cash (30 Sept.) – 909.6 123.6 n. a. Employees (30 Sept.) 71,473 69,546 + 2.8 Diff erences may occur due to rounding. This Annual Report 2019 of the TUI Group was prepared for the reporting period from 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019. -

UK OFFICE NOVEMBER 2010 REPORT Prepared By: Venessa Alexander UK Director

UK OFFICE NOVEMBER 2010 REPORT Prepared by: Venessa Alexander UK Director TOUR OPERATORS The following meetings were held with tour operators at World Travel Market. Stella Travel Services Meeting held with Brian Hawe, Contracts Manager. Stella represents 2 brands, Travel 2 and Travelbag. Travel 2 sells through the trade and Travelbag sells direct to the consumer. Both have shown increases in business to the US in 2010. Room night stats for the brands combined are as follows: Room nights to end of October: Clearwater 106 room nights + 20% St Pete 173 room nights + 22% Discussed training of their retail stores and awaiting a marketing plan from Brian for co-op opportunities with Travelbag. Expedia Met with Vicki Wickens, Head of Media Solutions. Discussed bigger promotional opportunities to include Orlando Tourism and SeaWorld Parks and Entertainment. Expedia are tied in with Nectar points which are a loyalty scheme with over 11 million members. If we can provide a big enough promotion for them, they would look to include some sort of nectar tie-in. Room night stats are 4454 to end of October. THG Holidays We were advised that that recent local newspaper advertisements in conjunction with Orlando Tourism generated 35 enquiries, 5 forward bookings and 35 room nights in 2011 from direct calls. We still have another advertisement left to run in January as part of this co-op activity. Total room night stats to end of October 2010 = 320 BA Holidays Met with Kathryn Brownrigg, Destination Manager. Room night stats are very low for BA compared to the number of passengers coming off their Tampa flight with only 800 on the books to end of October 2010. -

Beach Holidays Fy19 Results Presentation

THE UK’S LEADING ONLINE RETAILER OF BEACH HOLIDAYS FY19 RESULTS PRESENTATION November 2019 AGENDA CAUTIONARY STATEMENT FY19 Market Dynamics This presentation may contain certain forward-looking FY19 Financial Performance statements with respect to the financial condition, results, operations and businesses of the Company. Paul Meehan - CFO Forward looking statements are sometimes, but not always, identified by their use of a date in the future or such words as ‘anticipates’, ‘aims’, ‘due’, ‘will’, ‘could’, ‘may’, ‘should’, ‘expects’, ‘believes’, ‘intends’, ‘plans’, Evolution of Key Drivers ‘targets’, ‘goal’ or ‘estimates’. Simon Cooper – CEO These forward-looking statements involve risk and uncertainty because they relate to events and depend on circumstances that may or may not occur in the future. There are a number of factors that could cause actual results or developments to differ materially from those Q & A expressed or implied by these forward-looking statements, including factors outside the Company's control. The forward-looking statements reflect the knowledge and information available at the date of preparation of this presentation and will not be updated during the year. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as a profit forecast. 2 Paul Meehan Chief Financial Officer FY19 Market Dynamics FY19 Financial Performance Market Dynamics YOY Bookings Profile - OTB H1 H2 OTB Revenue growth of 1%, soft UK market impacted by: ‘lates’ market competitor discounting preceding Brexit deadline in H1 and continuing uncertainties -

Annual Report 2017 Contents & Financial Highlights

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS & FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS TUI GroupFinancial 2017 in numbers highlights Formats The Annual Report and 2017 2016 Var. % Var. % at the Magazine are also available online € 18.5 bn € 1,102.1restated m constant € million currency Turnover 18,535.0 17,153.9 + 8.1 + 11.7 Underlying EBITA1 1 1 + 11.7Hotels & %Resorts + 12.0356.5 % 303.8 + 17.3 + 19.2 Cruises 255.6 190.9 + 33.9 + 38.0 Online turnoverSource Markets underlying526.5 554.3 – 5.0 – 4.0 Northern Region 345.8 383.1 – 9.7 – 8.4 year-on-year Central Region 71.5 85.1 – 16.0 – 15.8 Western Region EBITA109.2 86.1 + 26.8 + 27.0 Other Tourism year-on-year13.4 7.9 + 69.6 + 124.6 Tourism 1,152.0 1,056.9 + 9.0 + 11.2 All other segments – 49.9 – 56.4 + 11.5 + 3.4 Mobile TUI Group 1,102.1 1,000.5 + 10.2 + 12.0 Discontinued operations – 1.2 92.9 n. a. Total 1,100.9 1,093.4 + 0.7 http://annualreport2017. tuigroup.com EBITA 2, 4 1,026.5 898.1 + 14.3 Underlying EBITDA4 1,541.7 1,379.6 + 11.7 56 %EBITDA2 4 23.61,490.9 % ROIC1,305.1 + 14.2 Net profi t for the period 910.9 464.9 + 95.9 fromEarnings hotels per share4 & € 6.751.36 % WACC0.61 + 123.0 Equity ratio (30 Sept.)3 % 24.9 22.5 + 2.4 cruisesNet capex and contentinvestments (30 Sept.) 1,071.9 634.8 + 68.9 comparedNet with cash 30 %(302 at Sept.) time 4of merger 583.0 31.8 n. -

2009-Fall-Dividend.Pdf

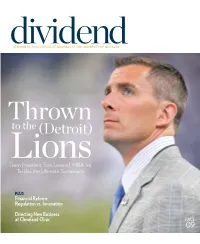

dividendSTEPHEN M. ROSS SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Thrown to the (Detroit) Lions Team President Tom Lewand, MBA ’96, Tackles the Ultimate Turnaround PLUS Financial Reform: Regulation vs. Innovation Directing New Business at Cleveland Clinic FALL 09 Solve the RIGHT Problems The Ross Executive MBA Advanced leadership training for high-potential professionals • Intense focus on leadership and strategy • A peer group of proven leaders from many industries across the U.S. • Manageable once-a-month format • Ranked #4 by BusinessWeek* • A globally respected degree • A transformative experience To learn more about the Ross Executive MBA call 734-615-9700 or visit us online at www.bus.umich.edu/emba *2007 Executive MBA TABLEof CONTENTS FALL 09 FEATURES 24 Thrown to the (Detroit) Lions Tom Lewand, AB ’91/MBA/JD ’96, tackles the turn- around job of all time: president of the Detroit Lions. 28 The Heart of the Matter Surgeon Brian Duncan, MBA ’08, brings practical expertise to new business development at Cleveland Clinic. 32 Start Me Up Serial entrepreneur Brad Keywell, BBA ’91/JD ’93, goes from odd man out to man with a plan. Multiple plans, that is. 34 Building on the Fundamentals Mike Carscaddon, MBA ’08, nails a solid foundation in p. 28 international field operations at Habitat for Humanity. 38 Adventures of an Entrepreneur George Deeb, BBA ’91, seeks big thrills in small firms. 40 Re-Energizer Donna Zobel, MBA ’04, revives the family business and powers up for the new energy economy. 42 Kickstarting a Career Edward Chan-Lizardo, MBA ’95, pumps up nonprofit KickStart in Kenya. -

Ujedinjena Kraljevina Profil Emitivnog Tržišta - Izdanje 2016

UJEDINJENA KRALJEVINA PROFIL EMITIVNOG TRŽIŠTA - IZDANJE 2016. OPĆI PODACI O TRŽIŠTU Političko uređenje: Ustavna monarhija. Vladar države: Kraljica Elizabeta II. (od 6. veljače 1952.). Predsjednica vlade: Theresa May (od 13. srpnja 2016.). Glavne političke stranke: laburistička, konzervativna, li- beralna. Administrativna podjela: Engleska, Škotska, Wales i Sje- verna Irska. Britanski prekomorski teritoriji: Angvila, Bermudi, Bri- tanski Djevičanski otoci, Britanski Antarktički teritorij, Falklandski otoci (Malvinski otoci), Gibraltar (iako je na europskom kontinentu), Kajmanski otoci, Montserrat, Dobna struktura: Pitcairn, Sveta Helena (uključuje Otok Ascension i Tristan - 0 – 14 godina – 17,82 % da Cunha), Južna Georgija i otočje Južni Sandwich, Britan- - 15 – 24 godine – 12,45 % ski indijskooceanski teritoriji (Otoci Chagos), otoci Turks i - 25 – 54 godine – 40,53 % Caicos. - 55 – 64 godine – 11,34 % - 65 i više godina – 17,86 % Površina: 244.820 km2. Kopno: 241.590 km2. Religija: kršćani (anglikanci, rimokatolici, prezbiterijanci, Voda: 3.230 km2. metodisti) 59,5 %, muslimani 4,4 %, hinduisti 1,3 %, atei- sti 25,7 %, ostali 2 %, ne izjašnjavaju se 7,2 %. Najveći gradovi: London (glavni grad, 8.674.000 stanov- nika), Manchester (2.550.000), Birmingham (2.440.000), Etničke skupine: bijelci 87,2 %, crnci (Afrika/Karibi) 3 %, Glasgow (1.220.000), Southhampton/Portsmouth Indijci 2,3 %, Pakistanci 1,9 %, miješani 2 %, ostali 3,7 %. (882.000), Liverpool (670.000), Cardiff, Bristol, Newcastle, Nottingham, Sheffield, Leeds, Bratford, Edinburgh. Jezici: engleski (službeni), velški (oko 20 % populacije Walesa), škotski (30 % populacije Škotske), škotski galski Stanovništvo: 65.110.034 stanovnika (lipanj 2016., pro- (oko 60.000 ljudi u Škotskoj), irski (oko 10 % populacije cjena za 2015.); 32.074.445 muškaraca i 33.035.589 žena. -

UK SALES CALL MANUAL Contents

Destination Australia Partnership UK SALES CALL MANUAL Contents The Destination Australia Partnership . 3 Contacts . 3 Location . 3 Tourism Australia - London . 4 State & Territory Tourism Organisations (STOs) . 5 Know Your Markets . 6 Consumer Profile . 6 International Visitor Arrivals . 6 Market Strategy . 6 Market Overview . 6 Market Updates . 6 Tourism Export Toolkit . 6 UK Market Profile . 6 UK Market Profile . 7 Trends . 8 Distribution . 8 Planning and Purchasing Travel . 8 Special Interest . 8 Planning a Visit to Market . 9 Top Tips for Sales Calls . 9 Aussie Specialist Program . 10 Premier Aussie Specialist . 10 Key Distribution Partners . 11 Other Trade Partners . 12 Travelling in the UK . 14 London . 14 Regional UK . 14 Map of the UK . 15 2 | UK Sales Call Manual The Destination Australia Partnership The Destination Australia Partnership (DAP) was DAP has two European offices – in London, and introduced in 2004 as a joint initiative between Frankfurt – with responsibilities as below: Tourism Australia and the State and Territory Tourism Organisations (STOs) in the European market . LONDON United Kingdom Ireland DAP ensures a better alignment with marketing Netherlands Nordic (Sweden, Norway, activities and operations, improves effectiveness in Finland, Denmark) marketing Australia overseas, reduces duplication Belgium and overlap with the region, and provides core FRANKFURT Germany services and training to trade and retail partners . Switzerland Austria Italy, France, Spain (represented by agencies) Contacts When including London in your visit to Europe, you are very welcome to visit the DAP team at our office in Australia House, central London . You would have the opportunity to obtain a market update from your respective STO representative and/or the Tourism Australia team, as well as provide a training session/product update for our Trade Team . -

Jet2.Com and Jet2holidays Launch Flights and Holidays to Sardinia for Summer 22

Jet2.com and Jet2holidays launch flights and holidays to Sardinia for Summer 22 1st April 2021: Jet2.com and Jet2holidays have today announced the launch of flights and holidays to Sardinia for Summer 22 from four UK bases, with the first flights departing at the start of May 2022. The addition of Sardinia for Summer 22 comes in response to demand from UK holidaymakers and will see the leading leisure airline and package holiday specialist operate six weekly flights from the UK. Jet2.com and Jet2holidays will operate to Sardinia from Birmingham, Leeds Bradford, Manchester and London Stansted Airports, with flights operating into Olbia Airport. This opens up the east coast of Sardinia and a range of resorts which host some of the best beaches in Europe. Sardinia offers customers the most authentic of Italian experiences and is on many people’s bucket list of must-see European beach destinations. With snow-white sand sloping into glimmering turquoise waters, customers can head to the Costa Smeralda for a glamorous seaside experience or head south of Olbia for a holiday with an authentic slant. Jet2holidays, the UK’s leading operator to Europe, is launching with a wide selection of hotels on sale, the majority enjoying a 4 & 5-star rating. Families and groups can also choose the privacy of a villa holiday with all the benefits of a package holiday, by booking through Jet2Villas. Resorts on sale in Sardinia include Porto Cervo, Baia Sardinia, Budoni, San Teodoro, Cannigione, San Pantaleo, Orosei and Pittulongu, as well as city breaks booked through Jet2CityBreaks to Olbia. -

Evaluation at Visitbritain and Visitengland Rumina Hill And

UK Inbound Seminar: Germany Richard Nicholls & Holger Lenz 20th February 2019 1 Key inbound market statistics • 3,38 million German visits to the UK 8.6% of total, 3rd in 2017 • £1.58 billion spending record 6.5% of total, 2nd in 2017 Source: International Passenger Survey by ONS 2 Visit and spend trends 4,000 Visits (000s) - left hand axis Spending (£m) - right hand axis £1,800 3,500 £1,600 3,000 £1,400 £1,200 2,500 £1,000 2,000 £800 1,500 £600 1,000 £400 500 £200 0 £0 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Source: International Passenger Survey by ONS 3 Year-to-date: January – September 2018 • Visits: 2.5 million down 5% vs. Jan-Sep 2017, weaker than Jan-Sep 2014-2017 • Visitors spend: £1.1billion down 11% vs. Jan-Sep 2017 record Source: International Passenger Survey by ONS 4 Where from, where to? The UK’s market share of German visits among competitor set 20% France 19% 23% 21% Austria 20% 18% 19% Spain 18% 18% 18% Italy 19% 18% 8% Netherlands 8% 5% 5% Poland 7% 8% 5% United Kingdom 5% 6% 3% Switzerland 3% 4% 1% Ireland 1% 1% 2027 2017 2007 Source: Oxford Economics (outbound overnight trips). German 5 states of residence data from IPS 2015. Economic outlook Cost of GBP in EUR • Exchange rate: favourable • Europe’s largest economy: narrowly 1.70 avoided recession in H2 2018 and 1.60 expected to bounce back in 2019 1.50 • Consumer confidence & spend are resilient but risks to the downside 1.40 • Germans view taking holidays as 1.30 important to ‘recharge’! 1.20 Economic indicators 2018 2019 2020 1.10 GDP 1.5% 2.3% 1.6% 1.00 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2016 2019 Consumer spending 1.1% 1.9% 2.0% Unemployment 5.2% 5.0% 4.9% Source: Bank of England, Oxford Economics 6 Leisure visits lead growth Journey purpose trend (visits 000s) • Amost half of all German visits are 2,000 made for holidays followed by one in four to friends/relatives in the UK. -

Ujedinjena Kraljevina Profil Emitivnog Tržišta - Izdanje 2015

UJEDINJENA KRALJEVINA PROFIL EMITIVNOG TRŽIŠTA - IZDANJE 2015. OPĆI PODACI O TRŽIŠTU Službeni naziv: Ujedinjeno Kraljevstvo Velike Britanije i Sjeverne Irske. Državno uređenje: Ustavna monarhija s dva zakonodav- na doma, vladar države: Kraljica Elizabeta II. (od 6. veljače 1952.). Glavni grad: London (10,310 milijuna stanovnika). Veći gradovi: Manchester (2,646 milijuna), Birmingham (2,515 milijuna), Glasgow (1,223 milijuna), Southampton/ Portsmouth (882.000), Liverpool (870.000), Cardiff, Bri- stol, Newcastle, Nottingham, Sheffield, Leeds, Bratford, Edinburgh. Administrativna podjela: Engleska, Škotska, Wales i Sje- verna Irska. Britanski prekomorski teritoriji: Angvila, Bermudi, Britan- ski Djevičanski otoci, Britanski Antarktički teritorij, Falklan- dski otoci (Malvinski otoci), Gibraltar (iako je na europskom kontinentu), Kajmanski otoci, Montserrat, Pitcairn, Sveta Vjerska pripadnost: kršćani (anglikanci, rimokatolici, Helena (uključuje Otok Ascension i Tristan da Cunha), Juž- prezbiterijanci, metodisti) 59,5 %, muslimani 4,4 %, hindu- na Georgija i otočje Južni Sandwich, Britanski indijskooce- isti 1,3 %, ateisti 25,7 %, ostali 2 %, ne izjašnjavaju se 7,2 %. anski teritoriji (Otoci Chagos), Otoci Turks i Caicos. Stopa rasta stanovništva: 0,54 %. 2 Površina: 244.820 km . Gustoća naseljenosti: 261 stanovnik/km2 (82,6 % sta- Broj stanovnika: 64.088.222. novništva živi u gradovima). Službeni jezik: engleski. Valuta: GBP (britanska funta). POLITIČKO UREĐENJE Ujedinjeno Kraljevstvo Velike Britanije i Sjeverne Irske lordova i monarha, Zastupnički je dom postao vodećim ustavna je nasljedna monarhija s parlamentarnim susta- nositeljem zakonodavne vlasti, a najvažnija mu je djelat- vom vlasti. nost raspravljanje o zakonskim prijedlozima i izglasava- nje zakona, u načelu na javnim plenarnim sjednicama. Sa- Najvišu zakonodavnu vlast ima dvodomni Parlament stoji se od vladajuće većine u kojoj se nalaze članovi vlade (Parliament) koji se sastoji od Zastupničkog ili Donjeg (koji čine tzv. -

Greece Destination Emerges As Year-Round Hotspot for Brits

TB 2303 2018 Cover 21/03/2018 15:37 Page 1 March 23 2018 | ISSUE NO 2,055 | travelbulletin.co.uk Greece Destination emerges as year-round hotspot for Brits this week 16 at home with eileen 8 bulletin briefing 13 cruising mexico 25 advice from the FCO Global says it Riviera Travel highlights agents need to might be time for a operators & hoteliers unveil some of the finer points know about digital detox their new programme additions of river cruising S01 TB 2303 2018 Start_Layout 1 21/03/2018 09:56 Page 2 S01 TB 2303 2018 Start_Layout 1 21/03/2018 09:56 Page 3 newsbulletin ELITE PERFORMERS... THE ELITE Travel Group held its awards evening at the Marriott Forest of Arden earlier this month. Pictured in a celebratory mood are, from the left (back row) Gemma Dicker, Travel with Kitts; Carly Charteris, Premier Holidays; Suzanne Warren, Sunvil; Julie Franklin, Mark Warner; and Chris Redfern, Jet2holidays; with (bottom row) Hazel Bryant, Travel with Kitts; David Holland, African Pride; Paul Fallows, Silversea; Michael Young-Richards, DoSomethingDifferent; and Patrick Devonshire, Flexible Autos. Cost of Living survey reveals cheapest & most expensive destinations for Brits SINGAPORE HOLDS onto the title of the most expensive city in region now accounts for three of the five most expensive the world for the fifth year running according to The Economist cities and for half of the top ten, while Tel Aviv is the sole Intelligence Unit's 2018 Worldwide Cost of Living Survey. Middle Eastern representative. The survey, which compares the price of more than 150 Roxana Slavcheva, editor of the survey, said: "Western items in 133 cities around the world, found that Singapore European cities dominate the top of the ranking once more.