Kohlberg's Moral Reasoning Stages Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief Overview of Developmental Theory, Or What I Learned in the FOLA Course

A Brief Overview of Developmental Theory, or What I Learned in the FOLA Course Jonathan Reams1 Abstract: This article describes the history and development of developmental theory from a lay person perspective. It covers some of the main strands of how developmental theory has grown, focusing on ego stage theories and dynamic skill theory as the main examples of soft and hard stage models. It also touches on how measures of these models relate to the theories. Reflections on the relative merits of each strand are considered, as well as implications for broadening the scope of awareness of developmental theory among the larger population of integrally informed practitioners. Keywords: Developmental theory, dynamic skill theory, ego development, metrics. Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 123 The Roots of Developmental Theory ..................................................................................... 123 Baldwin .............................................................................................................................. 123 Piaget .................................................................................................................................. 125 Transition to the Neo-Piagetian World: The Development of Diverse Streams of Thought . 126 An Examination of Stage Criteria: Functional, Soft and Hard Stages ............................... 128 Functional Models: Erikson and Sullivan -

Human Development Psychology 2.1 Developmental

Page 1 of 7 Human Development Psychology 2.1 Developmental psychology is the scientific study of changes that occur in human beings over the course of their life. Originally concerned with infants and children, the field has expanded to include adolescence, adult development, aging, and the entire lifespan. This field examines change across a broad range of topics including motor skills and other psycho-physiological processes; cognitive development involving areas such as problem solving, moral understanding, and conceptual understanding; language acquisition; social, personality, and emotional development; and self-concept and identity formation. Developmental psychology examines issues such as the extent of development through gradual accumulation of knowledge versus stage-like development—and the extent to which children are born with innate mental structures, versus learning through experience. Many researchers are interested in the interaction between personal characteristics, the individual's behavior, and environmental factors including social context, and their impact on development; others take a more narrowly-focused approach. Developmental psychology informs several applied fields, including: educational psychology, child psychopathology, and forensic developmental psychology. Developmental psychology complements several other basic research fields in psychology including social psychology, cognitive psychology, ecological psychology, and comparative psychology. Historical antecedents[edit] John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau are typically cited as providing the foundations of modern form of developmental psychology. William Shakespeare had his melancholy character Jacques (in As You Like It) articulate the seven ages of man: these included three stages of childhood and four of adulthood. In the mid- 18th century Jean Jacques Rousseau described three stages of childhood: infans (infancy), puer (childhood) and adolescence in Emile: Or, On Education. -

Certain Uncertainties Measuring Vertical Development and Its Impact on Leadership

Certain Uncertainties Measuring vertical development and its impact on leadership A (K)nowWhat? piece from MDV Consulting MDV Research and Innovation Alliance September 2019 Leadership and talent consultants Contents Preface 2 Key questions 3 Q1: What evidence shows us there are developmental stages in adulthood? 4 Selected theorists and practitioners in adult development – an approximate timeline 6 Q2: What are the criticisms of staged theories? 8 Q3: Can we measure developmental stage? 9 Q4: How do notions of reliability and validity sit with vertical development? 11 Constraints and limitations of conventional approaches to validity 12 Q5: Are the measures of developmental stage theoretically sound? 13 Q6: Do individuals and organisations find value in the idea of vertical development? 15 Case study 1 – The Value of Vertical 15 Q7: Do leaders at later development stages really perform better within VUCA environments? 16 Case study 2 – The CEO study 17 Q8: What facilitates or inhibits vertical development? 18 Case study 3 – How leadership development can transform a global organisation 21 Q9: Where are we now? 22 What do you think? 24 Get in touch 24 Notes 25 References 27 Appendix – table of selected theorists and practitioners in adult development 33 Author details 37 Certain Uncertainties Measuring vertical development and its impact on leadership A (K)nowWhat? article from MDV September 2019 “ In all affairs it's a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted.” Bertrand Russell (1940) Introduction This MDV piece of writing looks at the evidence base for vertical development: theoretical underpinnings, methodologies for measuring developmental stage, and its perceived utility and impact in organisations. -

Transcultural Communication Networks and Adult Cognitive Development Uwe Krüger

Photo: wallpaperstock.net Photo: Bringing social psychology back in: Transcultural communication networks and adult cognitive development Uwe Krüger „Networks of transnational and transcultural communication“ page 1 DGPuK Dortmund November 22-23, 2012 Outline 1. Introduction 2. Stages of individual development (Piaget, Kohlberg) 3. Stages of societal development (Habermas, Commons) 4. Implications for transcultural communication networks page 2 Motivation: What can social network analysis learn from psychology? . Social network analysis primarily addresses the “outer” characteristics of human interrelations . Hardly considers the inner processes of humans, which is the subject of psychology . Inner processes of humans may have an important impact on the outer characteristics of their relations For describing networks of transcultural communication approaches of adult cognitive development are important page 3 Introduction Individual Societal Implications Outline 1. Introduction 2. Stages of individual development (Piaget, Kohlberg) 3. Stages of societal development (Habermas, Commons) 4. Implications for transcultural communication networks page 4 Jean Piaget: Cognitive development proceeds in stages . Humans of different ages think in qualitatively different ways . mental structures, used to perceive and interpret the world, dramatically change . Successive decrease of egocentrism . Capacity for abstraction and for complex views and actions increases . Simple actions are combined, integrated and differentiated Photo: en.wikipedia.org Photo: page 5 Introduction Individual Societal Implications Jean Piaget identified 4 stages of cognitive development 1. Sensorimotor stage (age 0-2): . Simple actions: Sucking, Watching, Grasping, Pushing . Combination and coordination 2. Pre-operational stage (age 2-7): . Mental representations of physically absent objects . Unable to take others‘ perspectives . Magical and animist thinking predominates page 6 Introduction Individual Societal Implications Jean Piaget identified 4 stages of cognitive development 3. -

The Shape of Development 1

The shape of development 1 The shape of development Theo L. Dawson-Tunik Cognitive Science Hampshire College Amherst, MA 01002 (413) 222-0633 [email protected] Michael Commons Harvard Medical School Mark Wilson U. C. Berkeley, Graduate School of Education Resubmitted February 5, 2005 The shape of development 2 Abstract This project examines the shape of conceptual development from early childhood through adulthood. To do so we model the attainment of developmental complexity levels in the moral reasoning of a large sample (n=747) of 5- to 86-year-olds. Employing a novel application of the Rasch model to investigate patterns of performance in these data, we show that the acquisition of successive complexity levels proceeds in a pattern suggestive of a series of spurts and plateaus. We also show that there are 6 complexity levels represented in performance between the ages of 5 and 86; that patterns of performance are consistent with the specified sequence; that these findings apply to both childhood and adulthood levels; that sex is not an important predictor of complexity level once educational attainment has been taken into account; and that both age and educational attainment predict complexity level well during childhood, but educational attainment is a better predictor in late adolescence and adulthood. Key words: moral development, Rasch model, IRT, conceptual development, Kohlberg, lifespan development The shape of development 3 The shape of development Introduction There has been much debate over the shape of cognitive development. Many models have been presented, ranging from those based on the notion that cognitive development is incremental or continuous (Bandura, 1977) to those that consider it to be discontinuous, involving transformations such as hierarchical integration (Case, 1987; Demetriou & Valanides, 1998; Fischer, 1980; Piaget, 1985) or the processes of nonlinear dynamics (Lewis, 2000; Smith & Thelen, 1993; van der Maas & Molenaar, 1995; van Geert, 1998). -

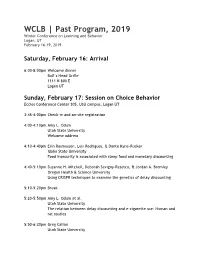

WCLB | Past Program, 2019 Winter Conference on Learning and Behavior Logan, UT February 16-19, 2019

WCLB | Past Program, 2019 Winter Conference on Learning and Behavior Logan, UT February 16-19, 2019 Saturday, February 16: Arrival 6:00-8:00pm Welcome dinner Bull’s Head Grille 1111 N 800 E Logan UT Sunday, February 17: Session on Choice Behavior Eccles Conference Center 305, USU campus, Logan UT 3:45-4:00pm Check-in and on-site registration 4:00-4:10pm Amy L. Odum Utah State University Welcome address 4:10-4:40pm Erin Rasmussen, Luis Rodrigues, & Dante Kyne-Rucker Idaho State University Food insecurity is associated with steep food and monetary discounting 4:40-5:10pm Suzanne H. Mitchell, Deborah Sevigny-Resetco, & Jordan A. Bromley Oregon Health & Science University Using CRISPR techniques to examine the genetics of delay discounting 5:10-5:20pm Break 5:20-5:50pm Amy L. Odum et al. Utah State University The relation between delay discounting and e-cigarette use: Human and rat studies 5:50-6:20pm Greg Callan Utah State University Self-regulated learning and delay of gratification: Conceptual links with research gaps 6:20-6:30pm Break 6:30-7:30pm Panel Discussion on Impulsivity Erin Rasmussen, Suzanne Mitchell, and Greg Callan Moderator: Amy Odum Monday, February 18: General Session and Student Showcase Eccles Conference Center 305, USU campus, Logan UT 3:45-4:00pm Check-in and on-site registration 4:00-5:00pm Student Showcase Akila Ram & Erin Bobeck Utah State University Morphine tolerance results in differences in protein kinase activation in the mouse periaqueductal gray Leela Afrose, Max Mcdermott, & Erin Bobeck Utah State University Behavioral characterization of a novel neuropeptide-receptor system, BigLEN-GPR171 Hayley Fisher, Alisa Pajser, Charday Long, & Charles L. -

Spring 2000 (Vol

1 quality of life of individuals as they adapt to the challenges of ADULT DEVELOPMENTS adulthood's ages and stages. This emphasis is in contrast to views and studies which emphasize decline, as studied in The Bulletin of the gerontology. SOCIETY FOR RESEARCH IN ADULT Typically at the symposium, investigators present data and DEVELOPMENT theories–as well as applications–on a variety of topics (Continued on the next page, first column) Spring 2000 (Vol. 9, No. 1) Contents ____________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ The Upcoming 15th Annual Adult Development Symposium In June . Page 1 The Unfolding Self-Portrait: Adult Development The Upcoming 15th Annual through Autobiography . Page 1 by Irene E. Karpiak Adult Development Symposium Message from the Executive Director . Page 5 by Mel Miller The SRAD Web Site . Page 5 Development at Any Cost?: Questioning Assumptions Theme: Adult Development and about the Necessity of Developmental Goals Transformative, Humanistic in the Professional Development of Teachers . Page 6 by Jennifer Garvey Berger and James Hammerman Education Papers and Handouts from the 1999 SRAD Symposium . Page 7 for the Next Millennium Postautonomous Ego Development: A Study Of Its Nature and Measurement . Page 8 by Susanne R. Cook-Greuter Presented by Notes from the 1999 SRAD Business Meeting . Page 9 The Society for Research in Adult by Patti Miller Longtime SRAD Members' New Book Includes Development and Contributions by Other SRAD Members . Page 9 The Straus Thinking and Learning Change Coming To The SRAD Listserv . Page 10 Editor's Notebook . Page 10 Center by Bernie Folta at Pace University SRAD Membership and Symposium Registration . Page 11 Combined Form for SRAD Membership and 2000 Symposium Registration . -

Complexity of Thinking and Levels of Self-Complexity Required to Sustainably Manage the Environment

Complexity of thinking and levels of self-complexity required to sustainably manage the environment Keith Norman Johnston January 2008 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University Keith Johnston: Complexity of thinking and levels of self-complexity required to sustainably manage the environment Certification of Originality This is to certify that this thesis is an original piece of work. The only material that is not all my own work is an excerpt from a paper jointly authored with my Principal Supervisor, included as Appendix Two. Keith Johnston 8 January 2008 2 Keith Johnston: Complexity of thinking and levels of self-complexity required to sustainably manage the environment Abstract Few decision makers face complexities that are as persistent and pervasive as those who are tasked with managing the environment or managing human impacts on the environment. This thesis investigates the capabilities of environmental managers to engage with the challenges they face. I address the over-arching question: What is the level of complexity of thinking and self-complexity that might be required to sustainably manage the environment and how does this compare with the current situation? I approach this question through consideration of relevant theories of environmental management and through the work of two theorists who have been prominent in the field of positive adult development, the study of the positive aspects of the further growth and development of people in adulthood. I consider two aspects of managers’ capabilities and development. The first is their capability as systems thinkers. In this I am primarily applying the theories and research about dialectical thinking of Michael Basseches (1984). -

Critical Studies of Education

Critical Studies of Education Volume 3 Series Editor Shirley R. Steinberg, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada Editorial Board Rochelle Brock, University of North Carolina, USA Annette Coburn, University of the West of Scotland, UK Barry Down, Murdoch University, Australia Henry A. Giroux, McMaster University, Ontario, Canada Tanya Merriman, University of Southern California, USA Marta Soler, University of Barcelona, Spain John Willinsky, Stanford University, USA We live in an era where forms of education designed to win the consent of students, teachers, and the public to the inevitability of a neo-liberal, market-driven process of globalization are being developed around the world. In these hegemonic modes of pedagogy questions about issues of race, class, gender, sexuality, colonialism, religion, and other social dynamics are simply not asked. Indeed, questions about the social spaces where pedagogy takes place—in schools, media, corporate think tanks, etc.—are not raised. When these concerns are connected with queries such as the following, we begin to move into a serious study of pedagogy: What knowledge is of the most worth? Whose knowledge should be taught? What role does power play in the educational process? How are new media re-shaping as well as perpet- uating what happens in education? How is knowledge produced in a corporatized politics of knowledge? What socio-political role do schools play in the twenty-first century? What is an educated person? What is intelligence? How important are socio-cultural contextual factors -

Positive Psychology and Constructivist Developmental Psychology

POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY AND CONSTRUCTIVIST DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY: A THEORETICAL ENQUIRY INTO HOW A DEVELOPMENTAL STAGE CONCEPTION MIGHT PROVIDE FURTHER INSIGHTS INTO SPECIFIC AREAS OF POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY by Paul Marshall A dissertation presented to the University of East London in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Applied Positive Psychology School of Psychology University of East London January 2009 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support, encouragement and open-mindedness of Dr. Ilona Boniwell, the creator and leader of this Msc degree. From the start Dr. Boniwell showed interest in my developmental perspective on positive psychology and encouraged me to pursue my theoretical orientation. I feel deep gratitude towards her for this. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr. Nash Popovic, my dissertation supervisor. His conceptual guidance and structural assistance greatly helped the unfolding of this dissertation. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……....……………………………………………… 1 ABSTRACT …..………….………………………………………………………. 3 1. INTRODUCTION: TIME FOR A VERTICAL DIMENSION IN POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY? ……………………………………………………………..…. 4 2. CONSTRUCTIVIST DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY: A LITERATURE REVIEW ………………………………………………………. 9 3. CONSTRUCTIVIST DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY: A CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF THE PARADIGM ……….…………………… 24 4. STAGE DEVELOPMENT AND INDIVIDUAL CONCEPTUALISATIONS OF WELL-BEING …………………………….……………………………….... 40 5. STAGE DEVELOPMENT AND VALUES -

Download Entire Volume

Published by the AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION Issue on tests and measures of positive adult development 2 bao BEHAVIORAL JOURNALS DEVELOPMENT BULLETIN Volume 19 | Number 4 | December 2014 ISSN 1942-0722 © 2014 AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION WWW.BAOJOURNAL.COM BEHAVIORAL DEVELOPMENT BULLETIN A Behavior Analysis Online Journal & An American Psychological Association Publication VOLUME 19 NUMBER 4 DECEMBER 2014 AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL bao ASSOCIATION JOURNALS EDITORS Michael Lamport Commons, Ph.D. Harvard Medical School Martha Pelaez, Ph.D. Florida International University ASSOCIATE EDITORS Carol Y. Yoder, Ph.D. Trinity University Gabriel Schnerch, M.A., Ph.D. Candidate, BCBA University of Manitoba Jesus Rosales-Ruiz, Ph.D. University of North Texas Josh Pritchard, Ph.D., BCBA-D Florida Institute of Technology Mareile Koenig, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, BCBA West Chester University Patrice Marie Miller, Ed.D. Salem State University and Harvard Medical School EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Anibal Gutierrez, Ph.D. Florida International University Cheryl Gabig, Ph.D. Lehman College/CUNY, Bronx, NY Darlene Crone-Todd, Ph.D. Salem State University Dolleen-Day Keohane, Ph.D., CABAS®SBA Teachers College Columbia University Douglas Greer, Ph.D. Columbia University Edward K. Morris, Ph.D. University of Kansas Erik Mayville, Ph.D., BCBA-D Institute for Educational Planning Felicia Hurewitz, Ph.D. EdMent, Inc., Philadelphia Gary Novak, Ph.D. California State University Hayne W. Reese West Virginia University Henry D. Schlinger, Jr., Ph.D. California State University, Los Angeles Jack Apsche, Ed.D, ACPP The Apsche Center for Mode Deactivation Therapy Jacob L. Gewirtz, Ph.D. Florida International University Javier Virués-Ortega, Ph.D. University of Manitoba Jeanne Speckman, Ph.D. -

ABP Presentation

Constructed Development and Psychometrics: the Missing Link to Better Personality Data! Dr Darren Stevens Copyright © 2021 Dr Darren Stevens Outline of Today’s Talk What is Personality? What is OCEAN? What are Psychometrics? What is Psychometric Isomorphism? What is missing from the above? What is Constructed Development Theory? How CDT can fill the gap! Copyright © 2021 Dr Darren Stevens Why are we here? Let’s set the scene immediately: I have a LOT of information in this presentation and you will not be able to take it all in. I am simply setting the scene and if you’re interested, you can have the slides afterwards to read at your leisure. Do not think you must take it all in as you simply cannot. Our working memory will allow us to recall about 10% of this at best! The number of slides is never the problem. The amount of information on each slide IS the problem. So I’ve gone with that premise and we have 4000 slides :) What is Personality? What Copyright © 2021 Dr Darren Stevens The word personality itself stems from the Latin word persona, which refers to a theatrical mask worn by performers in order to either project different roles or disguise their identities. Whatever the behaviour, personologists—as those who systematically study personality are called—examine how people differ in the ways they express themselves and attempt to determine the causes of these differences. Personality is defined as the characteristic sets of behaviours, cognitions, and emotional patterns that evolve from biological and environmental factors. While there is no generally agreed upon definition of personality, most theories focus on motivation and psychological interactions with one's environment.