Print Whole U (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DDR Catalogue 2021-1.Pdf

Back in the GDR I am not a German citizen. I did not live in the German Democratic Republic (1949 -1990). But I am a historian. The past for me, is a country I continue to live in. The past informs my present and from the early days of opening an art gallery in Berlin, the GDR has deeply interested me. In 2012, whilst visiting Berlin, I was most fortunate to view the incredibly profound exhibition, The Shuttered Society: Art Photography in the GDR 1949-1989. This was the first comprehensive exhibition of art photography, in relation to communist East Germany. Shuttered Society comprised hundreds of photographs from 34 photographers which critically reflected on the GDR. Shuttered Society was profound in its humanity. Profound in its documentation of how other people, Communist Germans, lived a low-tech life on the brink of dissolution. Profound in the way people can lead everyday lives, with humour and dignity, amidst a brutal ideological surveillance and yet remain at core people we recognise. The Shuttered Society percolated into memory to the point that my colleague Laura Thompson, Director of the Berlin gallery and I have been collecting Flea Market photographs, depicting as they often do, personal moments and humorous images of life under the old GDR. These GDR images are almost Polaroid moments from a society that did not use the instant, throw away technology that was early Polaroid. The images are all black and white. This is not art photography, but it is people photography. They are photographs of moment and mood; of a time of some foreignness and collective dignity. -

German Documentaries 2009 501 24H BERLIN a Day in the Life by Volker Heise BERLIN | DAILY LIFE | CITIES | PORTAIT

Dearest readers and users of this catalogue, there’s life in the old dog yet! field of interpersonal relationships. And this year, as is to be This is especially true of the “german documentaries“ expected in Germany, numerous films deal with the darkest catalogue, which after more than ten editions had become reaches of our country’s Nazi past. a tradition. When we announced one year ago that begin- Many of the films listed here premiered at major internatio- ning in 2009 it would no longer appear in printed form but nal festivals, and some of them have won prizes at home only online at www.german-documentaries.de, we had not and abroad. This, too, might be an incentive for you to reckoned with the ongoing fascination of the printed word request some of the films in the catalogue, to view them, and image. You, the users of this brochure, convinced us to use them and maybe even to buy them. Our brochure that the printed era has not yet come to an end. Amidst “german documentaries” is intended as a guide to help the hustle and bustle of a market, the printed catalogue navigate you through the German documentary film lands- still proves irreplacable for quickly looking up a film title, cape. We, the independent writers, directors, and produ- gaining an overview of a favourite subject matter, or in a cers who have joined together in the German Documentary pinch, even tearing out a page or two to read later. Association, are continually lobbying for the documentary So here it is in its old familiar form with its customary clas- film genre at home and abroad. -

Spurring to Action Wunderbar GERMANY in TURMOIL the Merkel Center Holds – but Barely, America’S Retreat and Donald Trump’S Refusal to Together Says Günter Bannas

$ 2.00 US October 2018 ISSN 1864-3965 Facing off What’s in store for the trans-Atlantic relationship? German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy and Munich Security Conference Chairman Wolfgang Ischinger assess the situation. pages 2 – 4 PICTURE ALLIANCE/AP PHOTO/JESCO DENZEL IN THIS ISSUE Spurring to action Wunderbar GERMANY IN TURMOIL The Merkel center holds – but barely, America’s retreat and Donald Trump’s refusal to together says Günter Bannas. Meanwhile, violence lead are putting the trans-Atlantic alliance at risk and protests in Chemnitz are causing an uproar, observes Peter Koepf. And a new A greeting from President BY THEO SOMMER generation of politicians is gearing up to Frank-Walter Steinmeier take over, writes Lutz Lichtenberger. pages 6–8 e live in perilous times in an imperiled Pessimists in Europe assume that America’s inward ristotle once described friendship world. The most dramatic shift of power turn will continue. In 15 to 20 years, whites will be as “a single soul dwelling in two Wand wealth since the ascent of the United a minority, they point out. This will weaken ties with Abodies.” In the case of the friend- BULLS IN THE CHINA SHOP States to worldwide dominance a hundred years ago Europe and sap the trans-Atlantic commitment. ship between the US and Germany, that The trade war between the US and the puts an end to 500 years of Western (and white) European optimists assume that the US pullback from “single soul” is our shared belief in democ- Middle Kingdom is about more than just hegemony. -

The Berlin Times Tells It As It Is

A special edition of The German Times marking October 3rd, the Day of German Unity THE VENTURE CAPITAL “Poor but sexy” no more. With real estate prices on the rise, is the German capital losing its unique allure among European metropolises? The Berlin Times tells it as it is PARTY LIKE IT’S 1929 BASKETBALL NEVER STOPS THE RAVAGES OF TIME CAPITAL CRIBS The hit TV show Berlin Babylon portrays The Alba basketball team has developed From Russian spies to haunted houses: The boom in luxury apartment buildings is the people and the excitement in the city a one-of-a-kind youth program – to find the The photographer Ciarán Fahey has captured but one reason for an increasingly tight real in its final years of freedom during the next roundball star and teach all kids how both glorious and obscure Berlin relics of a estate market. Who gets to live in the city Roaring Twenties. page 3 to play the game. page 5 time gone by. pages 6–7 tomorrow? page 8 A tale of many cities Facets of meaning abound – in an ever-changing city. The novelist Annett Gröschner tells the tale of Berlin today erlin, Prenzlauer Allee, after the other. But there’s also and apartments – especially in Ten years after the start of the performance “Die Zeit schlägt Thus far, anyone who has just behind the Ringbahn the well-dressed woman who, on the east – seemed to belong to no financial crisis, it is clear who dich tot” (Time beats you to come here with great plans and Bsubway line. -

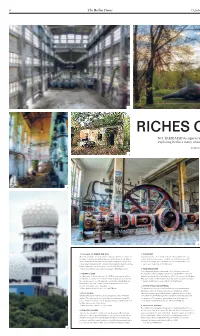

The Berlin Times NO TRESPASSING Signs Never Stopped C Exploring

6 The Berlin Times October 2018 1 RICHES OF RUINS NO TRESPASSING signs never stopped Ciarán Fahey from exploring Berlin’s many abandoned and forgotten buildings BY PETER H. KOEPF 6 5 9 1 COLOSSUS OF CEMENT AND IRON 5 TOP SECRET After 100 productive years, German reunification spelled the demise of Vogelsang was one of the few military sites the Soviets built themselves. the VEB Coswig Chemical Plant, which operated this factory in Rüders- They mostly took over German ones, but this one, all 5,800 hectares of it, dorf. A barbed-wire fence did not stop Ciarán Fahey from sizing up this was top secret – they built nuclear weapons here. Let’s be thankful it’s no industrial-era cathedral, which started producing animal feed phosphates longer in use. // Vogelsang, 16792 Zehdenick back in 1899 and continued to do so even after World War II. // Chemiewerk Rüdersdorf, Gutenbergstraße, 15562 Rüdersdorf 6 TRABI GRAVEYARD This old garage began to rot during the GDR. It houses dozens of 2 THE FUN’S OVER automobiles in various stages of decline, including a EZ P70 Zwickau In 1969, on the 20th anniversary of the GDR, the government gifted manufactured in the fifties, a Sachsenring P70, forerunner of the Trabant its subjects a second television channel and a public amusement park, P50, and a number of Moskvitches from Russia in very critical condition. the only permanent one if its kind in the country: the VEB Kulturpark // Trabiwerkstatt, Schönerlinder Straße 5, 13127 Berlin Plänterwald. The roller coaster and Ferris wheel have now rusted through, and the dinosaurs have died out. -

PETER JOSEPH LENNÉ PRIZE 2016 Landscape Architecture and Open Space Planning Competition

PETER JOSEPH LENNÉ PRIZE 2016 Landscape Architecture and Open Space Planning Competition TASK A – REGIONAL SPREEPARK BERLIN – From “Lost Garden” to a new type of park Scenery for a new definition of park INDEX Part 1 The Task 1.1 Reason and objective 2 1.2 Object of the call for tenders 4 1.3 General planning conditions 8 1.4 The task 9 1.5 Formats/sheet lines/design 12 1.6 Work required 12 Part 2 The Process 2.1 Initiator 13 2.2 Committee of experts for the Peter Joseph Lenné Prize 13 2.3 Type of process 13 2.4 Principles 13 2.5 Karl Foerster Commendation 13 2.6 Announcement/information/deadlines 13 2.7 Eligibility 14 2.8 Access to documents 14 2.9 Understanding the call for tenders documents 14 2.10 Submitting work/identification 14 2.11 Jury/process/results 14 2.12 Data capture/data protection 15 2.13 Ownership/copyright 15 2.14 Further use 15 2.15 Liability and return of work 15 2.16 Prizes 15 Part 3 The Annexes 3.1 Work plans 16 3.2 Documents 16 3.3 Form 16 3.4 Address of the initiator 16 Sources 16 PART 1 THE TASK 1.1 Reason and objective Photo: Grün Berlin Spreepark Berlin The Spreepark was opened in 1969 as the “Kulturpark Plän- terwald” right next to the River Spree. It was the only amuse- ment park in former East Germany (the German Democratic Republic, or GDR) and after reunification, also the only facil- ity of this type in the whole of Berlin to remain open all-year- round. -

District Election Program As

District Election Program 2021 Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Treptow- Köpenick Green content for Berlin's greenest District Contents Preamble.........................................................................................................................................................3 Preserving green spaces, protecting the climate and the environment.........................................................3 Preserving our forests and moors...............................................................................................................3 Urban and street trees................................................................................................................................4 Ecological land management......................................................................................................................4 Parks are oases for people and animals......................................................................................................4 Sustainable construction.............................................................................................................................5 Allotment gardens as diverse refuges.........................................................................................................5 Renewable energies and climate protection management........................................................................6 The blue district..........................................................................................................................................7 -

Beyond the Baustelle: Redefining Berlin's Contemporary Cinematic

Beyond the Baustelle: Redefining Berlin’s Contemporary Cinematic Brand as that of a Global Media City Luke Vincent Postlethwaite Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Languages, Cultures and Societies July, 2015 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2015 The University of Leeds and Luke Vincent Postlethwaite The right of Luke Vincent Postlethwaite to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements Over the last three years, I have received support and encouragement from a vast array of different sources at the University of Leeds, without which this project would not have been possible. I was lucky enough to be awarded the Joseph Wright Scholarship, financial support that has enabled me to complete my thesis. For this I must thank Professor Paul Cooke, whose encouragement and enthusiasm brought me to Leeds and whose help was instrumental in securing my scholarship. As my Supervisor, Professor Cooke has continued to challenge me throughout my research. His constructive feedback and suggestions have seen me take my research in directions I did not believe were possible and I will be forever grateful for that. This has been complemented by the advice of Dr Chris Homewood, who has always been willing to offer his thoughts on my work, especially influencing my project’s early development. -

Nocturnal Transgressions: Nighttime Stories from Berlin, the New European Nightlife Capital

Nocturnal Transgressions: Nighttime Stories from Berlin, the New European Nightlife Capital Enis Oktay Goldsmiths, University of London MPhil Thesis March 2015 I declare that the work presented in this doctoral thesis is my own. Enis Oktay 2 Acknowledgements The pages you are about to read are the result of a (way too) long process to which many people have contributed. I would like to dedicate this dissertation to all those dear ones – both known and unknown to me – who, in very different ways, have been a source of inspiration and have provided me with the motivation and patience to confront the difficulties of this tumultuous personal journey. First off, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisors John Hutnyk and Klaus-Peter Köpping for their constructive guidance, critical appreciation, challenging input, and encouraging support as well as for their friendship since they have wonderfully dismantled the hierarchy between student and teacher. I would also like to thank them for helping me overcome bureaucratic obstacles, e.g. visa problems, funding difficulties, recommendation letters, etc. In addition to this, I would like to thank everyone at the Centre for Cultural Studies for striving to mesh academics with politics and for challenging me to think differently, thereby fulfilling the department’s initial promise. I would also like to thank deeply my friends Emre Gözgü, Erdem Evren, Philip Hager and Dimitris Exarchos for our endless musings and discussions, our customary record-playing and intoxications, our nocturnal drifts and excursions, our chronic pessimism and melancholy as well as our redemptive laughter and joy, and our trust in and appreciation of the night.