Lessons for Rural Water Supply in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atpadi, Dist- Sangli Maharashtra

FORM 1 M APPLICATION FOR MINING OF MINOR MINERALS UNDER CATEGORY ‘B2’ FORLESS THAN AND EQUAL TO FIVE HECTARE (II) Basic Information :- 1 Name of the Mining Lease site: M/s. Gaytri Constructions for Shri Prakash Sidram Bhosale. Gut No-325, At- Kankatrewadi, Po- Kharsundi, Tal- Atpadi, Dist- Sangli ,Maharashtra 2 Location / site 17° 18'21.6"N (GPS Co-ordinates): 74° 48' 10.7"E 3 Size of the Mining Lease 1.2 hector (Hectare): 4 Capacity of Mining Lease (TPA): 32712 T/A average 5 Period of Mining Lease: 5 year 6 Expected cost of the Project: 25 lacks 7 Contact Information: M/s. Gaytri Constructions for Shri Prakash Sidram Bhosale., Gut No-325, At- Kankatrewadi, Po- Kharsundi, Tal- Atpadi, Dist- Sangli, Maharashtra Pre-Feasibility Report (PFR) for Stone Quarry M/s. Gaytri Constructions for Shri Prakash Sidram Bhosale., Gut No-325, At- Kankatrewadi, Po- Kharsundi, Tal- Atpadi, Dist- Sangli Maharashtra Prepared by Mahabal Enviro Engineers Pvt. Ltd. (QCI/NABET/ENV/ACO/16/06/0172) And GMC Engineers & Environmental Services Kolhapur www.gmcenviro.com E-Mail: [email protected], [email protected] Contact: 99211 90356, 8275266011 1.0 Brief Introduction: The M/s. Gaytri Constructions for Shri Prakash Sidram Bhosale. Owner of Gut No-325, At- Kankatrewadi, Po- Kharsundi, Tal- Atpadi, Dist- Sangli over a total area of 1.2 hector. The said land as been converted as non-agriculture for the purpose of small scale industries. Accordingly the quarry plan is prepared along with application form 1, PFR & EMP for the approval. 1 Need for the project: The region is economically backward mostly depends on seasonal forming. -

Sangram Kendra

Sangram Kendra District Taluka Village VLE Name Akola Akola AGAR PRAMOD R D Akola Akola AKOLA N KASHIRAM A Akola Akola AKOLA JP Shriram Mahajan Akola Akola AKOLA NW RP Vishal Shyam Pandey Akola Akola AKOLA NW RP-AC1 Vishal Shyam Pandey Akola Akola AKOLA OPP CO Dhammapal Mukundrao Umale Akola Akola AKOLA OPP CO-AC1 Dhammapal Mukundrao Umale Akola Akola AKOLA RP Rahul Rameshrao Deshmukh Akola Akola ANVI 2 Ujwala Shriram Khandare Akola Akola APATAPA Meena Himmat Deshmukh Akola Akola BABHULGAON A Jagdish Maroti Malthane Akola Akola BHAURAD MR Jagdish Gulabrao Deshmukh Akola Akola BORGAON M2 Amol Madhukar Ingale Akola Akola BORGAON MANJU N NARAYANRAO A Akola Akola DAHIHANDA RAJESH C T Akola Akola GANDHIGRAM Nilesh Ramesh Shirsat Akola Akola GOREGAON KD 2 Sandip Ramrao Mapari Akola Akola KANSHIVANI Pravin Nagorao Kshirsagar Akola Akola KASALI KHURD Kailash Shankar Shirsat Akola Akola KAULKHED RD DK Jyoti Amol Ambuskar Akola Akola KHADKI BU Kundan Ratangir Gosavi Akola Akola KHARAP BK Ishwar Bhujendra Bhati Akola Akola KOLAMBHI Amol Balabhau Badhe Akola Akola KURANKHED Sanjeevani Deshmukh Akola Akola MAJALAPUR Abdul Anis Abdul Shahid Akola Akola MALKAPUR V RAMRAO G Akola Akola MAZOD Sahebrao Ramkrushna Khandare Akola Akola MHAISANG Bhushan Chandrashekhar Gawande Akola Akola MHATODI Harish Dinkar Bhande Akola Akola MORGAON BHAK Gopal Shrikrishna Bhakare Akola Akola MOTHI UMRI A BHIMRAO KAPAL Akola Akola PALSO Siddheshwar Narayan Gawande Akola Akola PATUR NANDAPUR Atul Ramesh Ayachit Akola Akola RANPISE NAGAR Shubhangi Rajnish Thakare Akola Akola -

Pincode Officename Mumbai G.P.O. Bazargate S.O M.P.T. S.O Stock

pincode officename districtname statename 400001 Mumbai G.P.O. Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Bazargate S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 M.P.T. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Stock Exchange S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Tajmahal S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Town Hall S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Kalbadevi H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 S. C. Court S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Thakurdwar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 B.P.Lane S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Mandvi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Masjid S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Null Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Ambewadi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Charni Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Chaupati S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Girgaon S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Madhavbaug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Opera House S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Asvini S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Holiday Camp S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 V.W.T.C. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400006 Malabar Hill S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Bharat Nagar S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 S V Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Grant Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 N.S.Patkar Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Tardeo S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Mumbai Central H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 J.J.Hospital S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Kamathipura S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Falkland Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 M A Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Noor Baug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Chinchbunder S.O -

Temporal Models for Groundwater Level Prediction in Regions of Maharashtra

Temporal Models for Groundwater Level Prediction in Regions of Maharashtra Dissertation Report Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Technology by Lalit Kumar Roll No:10305073 Supervisors Prof. Milind Sohoni Prof. Purushottam Kulkarni a Department of Computer Science and Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Bombay June 2012 ii Abstract In this project work we perform analysis of groundwater level data in three districts of Maha- rashtra - Thane, Latur and Sangli. We have analyzed this data for more than 100 observation wells in each of these districts and developed seasonal models to represent the groundwater be- havior. Three different type of models were developed-periodic, polynomial and rainfall models. While periodic and polynomial models capture trends on water levels in observation wells, the rainfall model explores the correlation between the rainfall levels and water levels. The periodic and polynomial models are developed only using the groundwater level data of observation wells while the rainfall model also uses the rainfall data. All the data and the models developed with a summary of analysis is available at [1]. The larger aim is to build these models to predict tempo- ral changes in water level to aid local water management decisions and also give region specific input to Government planning authorities e.g. Groundwater Survey and Development Agency to flag water status with more information. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Groundwater as a Resource . .1 1.2 Societal Objectives and their Partition as Technical Objectives . .2 1.2.1 Single-Well and Regional Objectives . .3 1.3 GSDA Groundwater and Rainfall Datasets . -

District Census Handbook, Sangli

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SANGLI Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS OFFICE BOMBAY Printed in India by the Manager, Government Press and Book Depot, Nagpur, and Published by the Director, Government Printing and Stationery, Maharashtra State, BombaY-4. 1964- [price-Rs, 8-00] .~----------------------------------- ~~----~------------------------------------------~~ ~ N a J. '" o ..,o x iii III OIl - .. .... ' p ... ~OLHAPUR .q ~ 111.. U~ ..J j --0:: ..... .c · (J') -0 -..J (!) o ..._, .._, .. Z .. on\) U tr ~ ft~rftr III « : . : : j : ~ • : ~ • ~ en - ~ = - -;;;; } - i - ~ ~ :; ~ - 0 - --- - CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 Central Government Publications Census Report, Volume X-Maharashtra, is published in the following Parts: General Report I-C General Report (Contd.) II-A General Population Tables II-B (i) General Economic Tables U-B (ii) General Economic Tablea (Contd.) II-C Cultural and Migration Tables III Household Economic Tables ... Report on Housing and Establishments Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in Maharashtra Tables V-B Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in Maharashtra Ethnographic Notes VI (1-35) Village Surveys (35 monographs on 35 selected villages) VII-A ... Handicrafts in Maharashtra VU-B Fairs and Festivals in Maharashtra VIII-A ••• Administration Report-Enumeration (For official use only) VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation (For official use only) IX Census Atlas of Maharashtra X (1-:-13) Cities of Maharashtra (13 Volumes-Two volumes on Greater Bombay and One each on other eleven Cities) State -

Annexure-II Circle-Wise List of Aadhar Updation & Enrolment Facility

Annexure-II Circle-wise list of Aadhar Updation & Enrolment Facility Centres Name of the Post Offices where Aadhaar Enrolment cum Updation Centres Sl.No. have been set up ANDHARA PRADESH 1 Guntakal HO 2 Madanapalle HO 3 Rajampet HO 4 Dharmavaram HO 5 Adoni HO 6 Markapur HO 7 Proddatur HO 8 Pulivendla HO 9 Tirupati HO 10 Chandragiri HO 11 Srikalahasti HO 12 Anantapur HO 13 Chittoor HO 14 Cuddappah HO 15 Hindupur HO 16 Kurnool HO 17 Nandyal HO 18 Kanekal 19 Pamidi 20 Gooty RS 21 Thimmanacherla 22 Beerangi Kothakota S.O 23 Chowdepalli S.O 24 RAVINDRA NAGAR 25 YERRAMUKKAPALLI 26 NANDALUR 27 PORUMAMILLA 28 madakasira 29 Donakonda R.S. S.O 30 Holmespet S.O 31 Kalikiri S.O 32 Pakala S.O 33 Vayalpad S.O 34 Panagal S.O 35 Sainagar 36 Anantapur Collectorate 37 Anantapur Engg.college 38 Narpala 39 Yadiki 40 Jayalakshmipuram (Ananthapur) 41 Sri Venkateswarapuram 42 Arugonda 43 Bangarupalem 44 Chittor Bazar SO 45 Chittor Courtbuildings SO 46 Chittor Market S.O 47 Lalugardens SO 48 Murakambattu S.O 49 Nagamangalam S.O 50 Penumuru S.O 51 Thamballapalle S.O 52 Venkatagiri Kota S.O 53 JAYANAGAR 54 MANNUR (CUDDAPAH) 55 CHENNUR (CUDDAPAH) 56 KHAJIPET 57 VONTIMITTA 58 SIDDAVATAM 59 LAKKIREDDYPALLI 60 GALIVEEDU 61 Hindupur Extension 62 Gorantla 63 H.S.Mandir 64 Tanakallu 65 Dharmavaram RS 66 BETHAMCHERLA 67 BHAGYA NAGAR 68 KODUMUR 69 KNL. BAZAR 70 KNL. CHOWK 71 Collectorate Complex (Kurnool) 72 PEAPULLY 73 S.A.P. CAMP 74 SRI SAILAM 75 VELDURTHY 76 VELGODE 77 ADONI ARTS COLLEGE 78 ALUR 79 Besthavari Peta S.O 80 Chagalamarri S.O 81 Erragondapalem S.O 82 Komarole -

Satara South District Census Hand Book

GOVERNMENT OF BOMBAY SATARA SOUTH DISTRICT CENSUS HAND BOOK (Based on the 1951 Census) Printed at a1rE ASSOCIATED ADVERTISERS & PRINTERS LTD., T/.RDEO, BOMBAY 1. O"btainahle from the Governn'lent Publications Sales Depot, Institute of Science Building, Fort. Bombay (for purchasers in Bombay City), from the Government Book Depot, Chand Road Gardens, Bombay 4 (for orders from the mofussil) or through the High Commissioner for India, India House, Aldwych, London, W.C. 2, or through any l'ecognized Bookseller. , Price-Rs. 2-8-0 or £ 0-4-6 1952 CONTENTS PAGES A. General Population Tables A-I Area, Houses and Population 4 Towns and Villages classified by Population A-III 6 A-V 'fowns arranged Territorially with Population by Livelihood Classes 8 B. Economic Tables: B-I Livelihood Classes and Sub-Classes 10 B-I1 Secondary Means of Livelihood 20 B-IlI Employers, Employees and Independent Work~rs in Industries and Ser- vices by Divisions and Sub-Divisions 28 Index of Non-Agricultural occupations in the D~strict 72 c. Household and Age (Sample) Tables: C-I Household (Size and Composition) - .. 78 C-II Livelihood Classes by Age Groups '- .. 82 C-III Age and Civil Condition 86 C·IV Age and Literacy 96 C·V Single Year Age Returns 106 D. Social and Cultural Tablfs : D-I Languages: ',., (i) Mother Tongue 110 (ii) Bilingualism .. 115 D-II Religion 118 D-III Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes 118 ll-V (i) Displa&ed Persons by Year of Arrival in lIidia 120 (ii) Displaced Persons by I.ivelihood Classes •• 122 D·VI Non-Indian Nationals 122 D-VII Livelihood Classes by Educational Standards 124 D·VIII Unemployment by Educational Standards 128 E. -

List of Selected Candidates Belonging to SC Category for Award Of

List of selected candidates belonging to SC category for award of fellowship for the year 2013-14 under the scheme of Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship for SC Candidates during financial year 2013-14 Name of S.No. Candidate ID Domicile State Address of Candidate District Gender Category PH Place of Research Subject Candidate ADDANKI AMARAVATHID/O CHINA RGNF-2013- Andhra AMARAVATHI NARASANNASAMISRAGUDE WEST GODAVARI ANDHRA 1 14-SC-AND- Female SC No TELUGU Pradesh ADDANKI M [POST]NIDADAVOLU DISTRICT UNIVERSITY 54732 [MANDALAM]WEST GODAVARI DISTRICTANDHRA C/O G. VEERAIAHROOM RGNF-2013- NO:45- I-BLOCKSVU HOSTELS Andhra ANAKARLA Sri Venkateswara 2 14-SC-AND- FOR CHITTOOR Female SC No English Pradesh JHANSI RANI University 40586 MENS.V.UNIVERSITYTIRUPAT I - 517502 TIRUPATI 517502 ANIL KUMAR BOBBILI.C/O RGNF-2013- PROF P.BHANUMURTHY- Andhra ANIL KUMAR ANDHRA 3 14-SC-AND- DEPT OF GEOLOGY-ANDHRA VISAKHAPATNAM Male SC No GEOLOGY Pradesh BOBBILI UNIVERSITY 36816 UNIVERSITY- VISAKHAPATNAM 530003 H.NO. 2-32/23- RGNF-2013- VILL:KAMMUNOOR- MDL: Andhra University of 4 14-SC-AND- ANIL KUMAR P SARANGAPOOR- DIST: KARIMNAGAR Male SC No Telugu Pradesh Hyderabad 46361 KARIMNAGAR- PIN: 505454 JAGITIAL 505454 17-1-382/K/6/B/24 BALAJI RGNF-2013- Andhra ANIL KUMAR NAGARCHAMPAPET 5 14-SC-AND- HYDERABAD Male SC No Yet to be decided POWER SYSTEMS Pradesh YARAMALA SAIDABAD HYDERABAD 50566 500059 D. ANITHA D/O MALLAIAH[V] RGNF-2013- Andhra ANITHA TALLASINGARAM[M] JNTUH CHEMICAL 6 14-SC-AND- NALGONDA Female SC No Pradesh DONAKONDA CHOTUPPAL[D] NALGONDA HYDERABAD ENGINEERING 51608 NALGONDA 508252 RGNF-2013-14-SC 1 of 334 PAGES RGNF-2013-14-SC List of selected candidates belonging to SC category for award of fellowship for the year 2013-14 under the scheme of Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship for SC Candidates during financial year 2013-14 Name of S.No. -

District Census Handbook, Sangli

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SANGLI Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS DlRECI'ORATE BOMBAY PRINTED IN INDIA. BY THE MANAGER, GOVERNMENT pRE.._<::S AND STATIONERY STORES, KOLHAPUR AND PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR, GOVERNMENT PRINTING. STATIONERY AND PUBLICATIONS, MAHARASHTRA STATE. BOMBAy-400 004. 1985 ~ )I ';f li .§: "~6 Q. 'rJ Q ~" u "'6 0 8 x .~ Ii: .!;! ~ r .~ 3: • 00 .. '" "oS :J iHy • "0 (!) eGO ~, E Z 0" § ft.~b" _g ~ .~ i « <c.'-"o~ j g ! (!) !r Ul ? 4( I i .~ ~ 11 e S. 9 ~ l: ,g a::: ..... .,. ~ £ :f I I ~ ~ 11 ." ~ -Ii :! e a Ii i <5 I! <I: 8. ::;;: ~ ... ]i ~ i l! I- e ;! ~ ; ~ ~ ~ i D 'J j " -" ;; I ,. ~ .S !:Q is ~ I! ~ ~ ~ ,2'f ! ·Vi am Z c ~ ! ~E ~"! J 0 ;; t: 5 DC ] » 0 " ~ ." 5; ~ t ! ~ j -eo j .., !J! z '" I I £ ~f ::,., ~ l ... (" , <t ~ "\ \ .€ g. E CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 12-MAHARASHTRA SANGLI DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK ERRATA SLIP ----------_..,-.------~------------ Page Item Column For Read No. No. 2 3 4 5 8 Right side para second 1st line Columns 4 & 5 of the Columns 5 & 6 of the P. C. A. District P. C. A. and Colwnns 4 & 5 of village/urban P. C. A. 12 Fifth line of para second 341 341(i) 16 Table 12 9 0.77 70.77 (las t figure) 31 26-Kasabe Digraj 4 999 9,999 4O-Mhaisal (SangJi) 3 26 62 Total 4 /.,48,47 248,476 32 12-Kavalapur 5 PU PUC 34 Grand total 6 CHW-17 CHW-7 46 44-Lengare 4 518 5,518 47-B'llvadi-Khanapur 2 Vadi Khanapur Balvadi Khanapur 47 lO-Mahuli 16 R-(37.60) R(137.60) 54 31-Atpadi 5 H(6), PUC H(3), PUC, C 62 56-Jat 5 0 C 6 H, MH(3) PHC, H, MH(3), PHC, FPC, RP(lO) D, FPC, RP(lO) 64 104--Khojanwadi 4 (237) (235) 86 88-Shirala 5 P(4), (2), M, PUC P(4), M, H(2)PUC 6 MCW, PHC, HD, MCW, PHC,D, FPC, RP(3) FPC, RP(3) 91 8-Shirala 32 (Blank) 7 117 I-Miraj Tahsil (Rural) 28 54,7179 54,719 8-Shirala Tahsil (Total) 29 43,6504 46,504 123 Uran Islampur I(Line 3) 3 (Blank) 129 47-Erandoli 28 1,984 1,934 132 Ward No.2 14 654 659 Ward No.4 14 89 854 138 72-Wasambe 14 219 216 162 15-Banewadi '14 11 111 165 77-Rozawadi 16 27 17 171 58-Antri Bk. -

Notification for the Posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks Cycle – Iii/2020-2021 Maharashtra Circle

NOTIFICATION FOR THE POSTS OF GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – III/2020-2021 MAHARASHTRA CIRCLE ESTT/4-1/GDS ONLINE ENGAGEMENT/3RD CYCLE/2021 Applications are invited by the respective engaging authorities as shown in the annexure ‘I’against each post, from eligible candidates for the selection and engagement to the following posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks. I. Job Profile:- (i) BRANCH POSTMASTER (BPM) The Job Profile of Branch Post Master will include managing affairs of Branch Post Office, India Posts Payments Bank ( IPPB) and ensuring uninterrupted counter operation during the prescribed working hours using the handheld device/Smartphone/laptop supplied by the Department. The overall management of postal facilities, maintenance of records, upkeep of handheld device/laptop/equipment ensuring online transactions, and marketing of Postal, India Post Payments Bank services and procurement of business in the villages or Gram Panchayats within the jurisdiction of the Branch Post Office should rest on the shoulders of Branch Postmasters. However, the work performed for IPPB will not be included in calculation of TRCA, since the same is being done on incentive basis.Branch Postmaster will be the team leader of the Branch Post Office and overall responsibility of smooth and timely functioning of Post Office including mail conveyance and mail delivery. He/she might be assisted by Assistant Branch Post Master of the same Branch Post Office. BPM will be required to do combined duties of ABPMs as and when ordered. He will also be required to do marketing, organizing melas, business procurement and any other work assigned by IPO/ASPO/SPOs/SSPOs/SRM/SSRM and other Supervising authorities. -

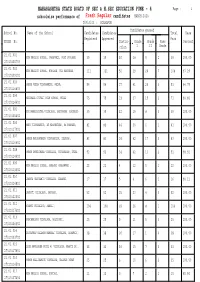

School Wise Result Statistics Report

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : KOLHAPUR Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 21.01.001 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, PAWARWADI, POST SAYGAON, 39 39 10 18 9 2 39 100.00 27310101703 21.01.002 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, HUMGAON, VIA PANCHWAD, 111 111 52 29 20 7 108 97.29 27310109102 21.01.003 SHREE VENNA VIDYAMANDIR, MEDHA, 96 96 27 41 20 3 91 94.79 27310116803 21.01.004 MAHARAJA SHIVAJI HIGH SCHOOL, KUDAL 75 75 23 27 19 2 71 94.66 27310124602 21.01.005 NAV MAHARASHTRA VIDYALAYA, SHIVNAGAR (RAIGAON) 39 39 12 19 8 0 39 100.00 27310101402 21.01.006 MERU VIDYAMANDIR, AT WAGHESHWAR, PO.BHANANG, 81 81 44 30 6 1 81 100.00 27310117001 21.01.007 SHREE BHAIRAVNATH VIDYAMANDIR, KELGHAR, 83 83 24 42 17 0 83 100.00 27310110902 21.01.008 SHREE DHUNDIBABA VIDYALAYA, VIDYANAGAR, KUDAL 92 92 34 42 13 2 91 98.91 27310124402 21.01.009 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KHARSHI (BARAMURE), 22 22 4 12 5 1 22 100.00 27310113302 21.01.010 JANATA MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KARANDI, 17 17 5 4 6 1 16 94.11 27310124801 21.01.011 JAGRUTI VIDYALAYA, SAYGAON, 52 52 25 23 4 0 52 100.00 27310102002 21.01.012 KRANTI VIDYALAYA, SAWALI, 104 104 69 26 8 1 104 100.00 27310117302 21.01.013 PANCHKROSHI VIDYALAYA, MALCHONDI, 25 25 9 11 5 0 25 100.00 27310106502 21.01.014 DATTATRAY KALAMBE MAHARAJ VIDYALAYA, DAPAWADI, 38 38 20 17 1 0 38 100.00 27310103702 21.01.015 LATE ANNASAHEB PATIL M. -

List of Operational Atal Tinkering Labs in India

LIST OF OPERATIONAL ATAL TINKERING LABS IN INDIA TRANCHE 1 S.N. STATE/ UT DISTRICT ATL UID CODEUDISE CODE NAME OF SCHOOL SANCTION TIME 1 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND NORTH AND MIDDLE ANDAMAN 87707111 35030101603 Mar-18 JAWAHAR NAVODAYA VIDYALAYA PANCHAWATI 2 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND NORTH AND MIDDLE ANDAMAN 27662082 35030301201 Mar-19 GOVT SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL DIGLIPUR 3 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND SOUTH ANDAMAN 2a2a7978 35010300501 Dec-16 GOVERNMENT MODEL SR SEC SCHOOL 4 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND SOUTH ANDAMAN b5c69604 35010101803 Mar-18 UMMAT PUBLIC SCHOOL 5 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND SOUTH ANDAMAN 16624626 35010104101 Mar-19 GOVT SECONDARY SCHOOL DAIRY FARM 6 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND SOUTH ANDAMAN 14354013 35010104504 Mar-19 GOVT SR SEC SCHOOL HADDO TELUGU MEDIUM 7 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND SOUTH ANDAMAN 22143132 35010104710 Mar-19 GOVERNMENT BOYS SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL 8 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND SOUTH ANDAMAN 77592418 35010104725 Mar-19 GOVT SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL MOHANPURA 9 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND SOUTH ANDAMAN 23283143 35010104503 Mar-19 GOVT SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL HADDO 10 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND SOUTH ANDAMAN 19496812 35010104001 Mar-19 GOVT SR SEC SCHOOL SCHOOL LINE 11 ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 32232050 28225700208 Mar-18 APSWRSCHOOL JR COLLEGE BOYS 12 ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR bd682794 28223790340 Mar-18 A P MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE DHARMAVARAM 13 ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 14822117 28220600903 Mar-18 APSWR SCHOOL JR COLLEGE 14 ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 18362145 28225790591 Mar-18 APSWRSCHOOL/JR.COLLEGE (G),