Pierre Rivière and Anders Breivik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for the Forensic Analysis of Drugs Facilitating Sexual Assault and Other Criminal Acts

Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Guidelines for the Forensic analysis of drugs facilitating sexual assault and other criminal acts United Nations publication Printed in Austria ST/NAR/45 *1186331*V.11-86331—December 2011 —300 Photo credits: UNODC Photo Library, iStock.com/Abel Mitja Varela Laboratory and Scientific Section UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Guidelines for the forensic analysis of drugs facilitating sexual assault and other criminal acts UNITED NATIONS New York, 2011 ST/NAR/45 © United Nations, December 2011. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. List of abbreviations . v Acknowledgements .......................................... vii 1. Introduction............................................. 1 1.1. Background ........................................ 1 1.2. Purpose and scope of the manual ...................... 2 2. Investigative and analytical challenges ....................... 5 3 Evidence collection ...................................... 9 3.1. Evidence collection kits .............................. 9 3.2. Sample transfer and storage........................... 10 3.3. Biological samples and sampling ...................... 11 3.4. Other samples ...................................... 12 4. Analytical considerations .................................. 13 4.1. Substances encountered in DFSA and other DFC cases .... 13 4.2. Procedures and analytical strategy...................... 14 4.3. Analytical methodology .............................. 15 4.4. -

Download Resume

Curriculum Vitae Full Name: David M. Marks, M.D. Contact: [email protected] Mobile (619) 822-7117 Credentials: Diplomate, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (Psychiatry) Subspecialty Certification in Psychosomatic Medicine Diplomate, American Board of Pain Medicine Position Title: Associate Professor Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Department of Community and Family Medicine Duke University Medical Center Duke Clinical Research Institute Duke Pain and Palliative Care Clinic Education: Institution & Location Degree Year Conferred Field of Study University of California at San Diego Fellowship 1999 - 2000 Consultation and San Diego, CA Liaison Psychiatry Medical College of Pennsylvania / Senior 1998 - 1999 Psychiatry Clinical Neuroscience Research Unit Resident Philadelphia, PA University of California at San Diego Resident 1995 - 1998 Psychiatry San Diego, CA University of Texas Medical Branch M.D. 1995 Galveston, TX Rice University B.A. 1991 Psychology Houston, TX Research and Professional Experience: Position Institution/Employer & Location Dates of Employment Attending Faculty Physician Duke Pain and Palliative Care Clinic 09/08-present (Chronic Pain Management) Attending Faculty Physician Duke University Medical Center, 07/06-present Inpatient Psychiatric Service, Emergency Service, Consultation/Liaison Service Attending Faculty Physician Durham Regional Hospital, 09/08-07/11 Consultation/Liaison Service Medical Director, Inpatient and Duke University Medical Center 07/06 – 02/07 Emergency Psychiatry Services Medical Director, CNS Division EStudy Site 05/05 -- 07/06 La Mesa, Oceanside, National City CA Chief Executive Officer/Medical Optimum Health Services 01/02 – 05/05 Director La Mesa, Oceanside CA Chief of Staff Alvarado Parkway Institute 01/04 – 01/05 1 La Mesa, CA Page _____________________________________________________________________ David M. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 De Juan Et Al

US 200601 10428A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 de Juan et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) METHODS AND DEVICES FOR THE Publication Classification TREATMENT OF OCULAR CONDITIONS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Eugene de Juan, LaCanada, CA (US); A6F 2/00 (2006.01) Signe E. Varner, Los Angeles, CA (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/427 (US); Laurie R. Lawin, New Brighton, MN (US) (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: Featured is a method for instilling one or more bioactive SCOTT PRIBNOW agents into ocular tissue within an eye of a patient for the Kagan Binder, PLLC treatment of an ocular condition, the method comprising Suite 200 concurrently using at least two of the following bioactive 221 Main Street North agent delivery methods (A)-(C): Stillwater, MN 55082 (US) (A) implanting a Sustained release delivery device com (21) Appl. No.: 11/175,850 prising one or more bioactive agents in a posterior region of the eye so that it delivers the one or more (22) Filed: Jul. 5, 2005 bioactive agents into the vitreous humor of the eye; (B) instilling (e.g., injecting or implanting) one or more Related U.S. Application Data bioactive agents Subretinally; and (60) Provisional application No. 60/585,236, filed on Jul. (C) instilling (e.g., injecting or delivering by ocular ion 2, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/669,701, filed tophoresis) one or more bioactive agents into the Vit on Apr. 8, 2005. reous humor of the eye. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2006/0110428A1 R 2 2 C.6 Fig. -

New Drug Evaluation Monograph Template

© Copyright 2012 Oregon State University. All Rights Reserved Drug Use Research & Management Program Oregon State University, 500 Summer Street NE, E35, Salem, Oregon 97301-1079 Phone 503-947-5220 | Fax 503-947-1119 Class Update: Second Generation Antidepressant Medications Month/Year of Review: May 2014 Last Oregon Review: April 2012 PDL Classes: Psychiatric: Antidepressants Source Document: OSU College of Pharmacy New drug(s): vortioxetine (Brintellix®) Manufacturer: Takeda & Lundbeck/Forest levomilnacipran extended-release (Fetzima®) Dossier Received: Yes/Pending Current Status of Voluntary PDL Class: Preferred Agents: BUPROPION HCL TABLET/TABLET ER, CITALOPRAM TABLET/SOLUTION, FLUOXETINE CAPSULE/SOLUTION/TABLET, FLUVOXAMINE, MIRTAZEPINE TAB RAPDIS/TABLET, PAROXETINE TABLET, SERTRALINE ORAL CONC/TABLET, VENLAFAXINE TABLET, VENLAFAXINE ER Non-Preferred Agents: BUPROPRION XL, DESVENLAFAXINE (PRISTIQ ER), DULOXETINE (CYMBALTA®), ESCITALOPRAM, FLUOXETINE DF (PROZAC® WEEKLY), NEFAZODONE, PAROXETINE HCL (PAXIL CR®), SELEGILINE PATCH (ENSAM®), VILAZODONE (VIIBRYD®), OLANZAPINE/FLUOXETINE (SYMBYAX®) Status of the Voluntary Mental Health Preferred Drug List Currently, all antidepressants are available without prior authorization for non-preferred placement. Oregon law prohibits traditional methods of PDL enforcement on mental health drugs. Second generation antidepressants have been reviewed for clinical efficacy and safety and specific agents were chosen as clinically preferred; this eliminates a copay. Oregon’s Medicaid program currently -

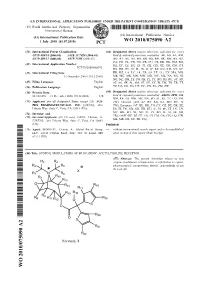

Wo 2010/075090 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 1 July 2010 (01.07.2010) WO 2010/075090 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C07D 409/14 (2006.01) A61K 31/7028 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, C07D 409/12 (2006.01) A61P 11/06 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US2009/068073 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (22) International Filing Date: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 15 December 2009 (15.12.2009) ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, (25) Filing Language: English SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, (26) Publication Language: English TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/122,478 15 December 2008 (15.12.2008) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): AUS- ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, PEX PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. -

Pharmacological Approach to Sleep Disturbances in Autism Spectrum Disorders with Psychiatric Comorbidities: a Literature Review

medical sciences Review Pharmacological Approach to Sleep Disturbances in Autism Spectrum Disorders with Psychiatric Comorbidities: A Literature Review Sachin Relia 1,* and Vijayabharathi Ekambaram 2,* 1 Department of Psychiatry, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, 920, Madison Avenue, Suite 200, Memphis, TN 38105, USA 2 Department of Psychiatry, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 920, Stanton L Young Blvd, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.R.); [email protected] (V.E.); Tel.: +1-901-448-4266 (S.R.); +1-405-271-5251 (V.E.); Fax: +1-901-297-6337 (S.R.); +1-405-271-3808 (V.E.) Received: 15 August 2018; Accepted: 17 October 2018; Published: 25 October 2018 Abstract: Autism is a developmental disability that can cause significant emotional, social and behavioral dysfunction. Sleep disorders co-occur in approximately half of the patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Sleep problems in individuals with ASD have also been associated with poor social interaction, increased stereotypy, problems in communication, and overall autistic behavior. Behavioral interventions are considered a primary modality of treatment. There is limited evidence for psychopharmacological treatments in autism; however, these are frequently prescribed. Melatonin, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and α agonists have generally been used with melatonin, having a relatively large body of evidence. Further research and information are needed to guide and individualize treatment for this population group. Keywords: autism spectrum disorder; sleep disorders in ASD; medications for sleep disorders in ASD; comorbidities in ASD 1. Introduction Autism is a developmental disability that can cause significant emotional, social, and behavioral dysfunction. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-V) classification [1], autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in domains of social communication, social interaction, restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. -

The Use of Stems in the Selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances

WHO/PSM/QSM/2006.3 The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances 2006 Programme on International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Quality Assurance and Safety: Medicines Medicines Policy and Standards The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

Use of Ropinirole for Restless Legs Syndrome Associated with Agitated

Articolo originale • Original article Use of ropinirole for restless legs syndrome associated with agitated depression: a case report Uso del ropinirolo nella sindrome da gambe senza riposo associata a depressione agitata: segnalazione di un caso Summary at the dose of 1.5 mg/day, improved S. Miano*, A. Talamo** ***, significantly both sleep disturbance and R. Ferri****, R. Tatarelli** We describe the unusual case of a young psychiatric symptoms (Table I). * This case supports the importance of Department of Paediatric, girl with agitated depression who was Sleep Disease Centre, Sapienza referred to our Sleep Centre, complain- checking for the existence of restless University of Rome, 2nd Medical ing severe insomnia. She underwent legs syndrome in young people whose School-Sant’Andrea Hospital, overnight polysomnography that dis- first episode of mood disorder is as- Rome; ** NESMOS Department, closed periodic limb movements during sociated with severe insomnia and to Sapienza University of Rome, 2nd Medical School-Sant’Andrea sleep associated with increased sleep eventually perform a complete poly- Hospital, Rome; *** Department latency, supporting the clinical diagno- somnographic study to confirm the of Psychiatry and Neuroscience sis of restless legs syndrome. Treatment clinical diagnosis and to evaluate the Program, Harvard Medical School, with the dopamine agonist ropinirole, outcome. Boston, Massachusetts; **** Department of Neurology I.C., Sleep Research Centre, Oasi Institute for Research on Mental Intoduction Retardation and Brain Aging (IRCCS), Troina, Italy One of the most frequent complaints in psychiatric disorders is insom- nia 1, but also the reverse holds true, i.e., sleep disturbances, including a wide range of disorders like insomnia, hypersomnia, restless legs/peri- odic limb movements during sleep (PLMS), obstructive sleep apnea, and parasomnias, are frequently associated with psychiatric disorders. -

Draft - Guideline on Pharmaceutical Development of Medicines for Paediatric Use": a Pragmatic Overview and 20 Constructive Proposals

Via electronic transmission To: Quality Working Party ([email protected]) Cc: Guido Rasi —Executive Director, EMA Cc: Dominique Maraninchi – Executive Director, Afssaps Cc: Agnieszka Laka—Document Management, EMA Cc: Kent Woods—Management Board Chair, EMA Cc: John Dalli—European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Policy, EC Cc: Patricia Brunko General Director Pharmaceutical Unit, EC Prescrire’s response to the public consultation on EMA/CHMP/QWP/180157/2011 "Draft - Guideline on Pharmaceutical Development of Medicines for Paediatric Use": a pragmatic overview and 20 constructive proposals Paris, 29 December 2011 Dear Sir or Madam, In May 2011, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) released for public consultation a draft guideline on the pharmaceutical development of medicines for paediatric use (1). The Prescrire team’s opinion on the draft is set out below. Introduction The pharmaceutical aspects of a medicine are important to its harm-benefit balance; they include its dosage form, excipients, dose strength or concentration, and packaging. 1/20 A strong, detailed Community guideline on the pharmaceutical aspects of medicines developed for children will be a key determinant of the quality of the treatments available for young patients in the European Union. Such a guideline will reinforce the advances expected from implementation of the European Paediatric Regulation (2). Measures to benefit children should focus first and foremost on their real needs. The priorities for the many healthy children in the European Union are antenatal care, postnatal follow-up and primary prevention: of serious infectious diseases (through vaccination), obesity, accidents in the home, etc. (3). Measures are also required to regulate and evaluate the many off-label uses of medicines that are useful to children but not authorised for paediatric use, and to ensure that the treatments available to children are accessible, convenient and safe. -

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation

Forensic Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Exactive Plus High-Resolution Accurate Mass Spectrometer and ExactFinder Software Kristine Van Natta, Marta Kozak, Xiang He Forensic Toxicology use Only Drugs analyzed Compound Compound Compound Atazanavir Efavirenz Pyrilamine Chlorpropamide Haloperidol Tolbutamide 1-(3-Chlorophenyl)piperazine Des(2-hydroxyethyl)opipramol Pentazocine Atenolol EMDP Quinidine Chlorprothixene Hydrocodone Tramadol 10-hydroxycarbazepine Desalkylflurazepam Perimetazine Atropine Ephedrine Quinine Cilazapril Hydromorphone Trazodone 5-(p-Methylphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin Desipramine Phenacetin Benperidol Escitalopram Quinupramine Cinchonine Hydroquinine Triazolam 6-Acetylcodeine Desmethylcitalopram Phenazone Benzoylecgonine Esmolol Ranitidine Cinnarizine Hydroxychloroquine Trifluoperazine Bepridil Estazolam Reserpine 6-Monoacetylmorphine Desmethylcitalopram Phencyclidine Cisapride HydroxyItraconazole Trifluperidol Betaxolol Ethyl Loflazepate Risperidone 7(2,3dihydroxypropyl)Theophylline Desmethylclozapine Phenylbutazone Clenbuterol Hydroxyzine Triflupromazine Bezafibrate Ethylamphetamine Ritonavir 7-Aminoclonazepam Desmethyldoxepin Pholcodine Clobazam Ibogaine Trihexyphenidyl Biperiden Etifoxine Ropivacaine 7-Aminoflunitrazepam Desmethylmirtazapine Pimozide Clofibrate Imatinib Trimeprazine Bisoprolol Etodolac Rufinamide 9-hydroxy-risperidone Desmethylnefopam Pindolol Clomethiazole Imipramine Trimetazidine Bromazepam Felbamate Secobarbital Clomipramine Indalpine Trimethoprim Acepromazine Desmethyltramadol Pipamperone -

Current Phase III Clinical Trials

Toolbox: Current phase III clinical trials Tiffany-Jade Kreys, PharmD1 1Assistant Professor of Pharmacy Practice University of the Incarnate Word Feik School of Pharmacy, San Antonio, Texas KEYWORDS clinical trials, depression, bipolar, schizophrenia, medications Table 1. Novel Agents for Major Depression, Bipolar Disorder, and/or Schizophrenia Product Name Sponsor Indication Mechanism of Action (previous name) Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/mhc/article-pdf/2/6/138/2094102/mhc_n129046.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Amitifadine Euthymics MDD Triple Reuptake Inhibitor (EB-1010) Bioscience (1:2:8 ratio of serotonin: norepinephrine: dopamine inhibition) Bitopertin Roche Schizophrenia Glycine reuptake inhibitor (RG1678) Enhances NMDA receptor activity Brexpiprazole Lundbeck MDD, Claimed to have "broad activity across multiple monoamine (OPC-34712) Otsuka America Schizophrenia systems and exhibits reduced partial agonist activity at D2 Pharmaceuticals receptors and enhanced affinity for specific serotonin receptors" Cariprazine Forest Laboratories BPAD, MDD adjunct D3-preferring/D2 receptor partial agonist (RGH-188) therapy, Schizophrenia Citalopram/ PharmaNeuro- MDD 5HT2A/D4 antagonist Pipamperone Boost (PNB01) Edivoxetine Eli Lilly MDD adjunct therapy Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (LY2216684) Vortioxetine Lundbeck MDD In vitro studies: 5HT3 and 7 receptor antagonist, 5HT1B partial (LUAA21004) Takeda agonist, 5HT1A agonist, serotonin transporter inhibitor Pharmaceuticals In vivo: Increases serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, -

Patent Application Publication ( 10 ) Pub . No . : US 2019 / 0192440 A1

US 20190192440A1 (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No. : US 2019 /0192440 A1 LI (43 ) Pub . Date : Jun . 27 , 2019 ( 54 ) ORAL DRUG DOSAGE FORM COMPRISING Publication Classification DRUG IN THE FORM OF NANOPARTICLES (51 ) Int . CI. A61K 9 / 20 (2006 .01 ) ( 71 ) Applicant: Triastek , Inc. , Nanjing ( CN ) A61K 9 /00 ( 2006 . 01) A61K 31/ 192 ( 2006 .01 ) (72 ) Inventor : Xiaoling LI , Dublin , CA (US ) A61K 9 / 24 ( 2006 .01 ) ( 52 ) U . S . CI. ( 21 ) Appl. No. : 16 /289 ,499 CPC . .. .. A61K 9 /2031 (2013 . 01 ) ; A61K 9 /0065 ( 22 ) Filed : Feb . 28 , 2019 (2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 / 209 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 /2027 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 31/ 192 ( 2013. 01 ) ; Related U . S . Application Data A61K 9 /2072 ( 2013 .01 ) (63 ) Continuation of application No. 16 /028 ,305 , filed on Jul. 5 , 2018 , now Pat . No . 10 , 258 ,575 , which is a (57 ) ABSTRACT continuation of application No . 15 / 173 ,596 , filed on The present disclosure provides a stable solid pharmaceuti Jun . 3 , 2016 . cal dosage form for oral administration . The dosage form (60 ) Provisional application No . 62 /313 ,092 , filed on Mar. includes a substrate that forms at least one compartment and 24 , 2016 , provisional application No . 62 / 296 , 087 , a drug content loaded into the compartment. The dosage filed on Feb . 17 , 2016 , provisional application No . form is so designed that the active pharmaceutical ingredient 62 / 170, 645 , filed on Jun . 3 , 2015 . of the drug content is released in a controlled manner. Patent Application Publication Jun . 27 , 2019 Sheet 1 of 20 US 2019 /0192440 A1 FIG .