Haiti: Crisis, Western Imaginings, and Visual Rhetoric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Praise of Tim Burton

In Praise of Tim Burton By William Woof Spring 1998 Issue of KINEMA IN PRAISE OF TIM BURTON: FINDING THE MASTERPIECE IN MARS ATTACKS ”Science fiction is a literary province I used to visit fairly often; if I now visit it seldom, that isnotbecause my taste has improved but because the province has changed, being now covered with new building estates, in a style I don’t care for. But in the good old days I noticed that whenever critics said anything about it, they betrayed great ignorance.... A great many writers use it for satire; nearly all the most pungent criticism of the American way of life takes this form, and would at once be denounced as un-American if it ventured into any other. C.S. Lewis”(1) Published two years before his death in 1963, Lewis’s comments on critical methods and practices were written in order to highlight the dangers of pigeonholing the entire corpus of a popular genre according to literary prejudices or the presumed practices of its readers. Lewis was acutely aware of the wide literary spectrum covered by science fiction: from mythologizing to hack writing, from eulogies of technology to outright flights of fantasy. But he had also understood those peculiarities of the American naturethat combine a fast-talking entrepreneurship with a productive and industrious ingenuity to create a national character highly prone to deep, xenophobic suspicions of ”alien” ideologies. We may safely assume that had his evaluation been extended to the ”new building estates” of America’s ”golden age” of B-grade SF films of the 1950’s, his analysis would have assimilated not only their tacky, exploitative nature buttheir glorification of technology as well. -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Shrapnel

SHRAPNEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Wharton | 272 pages | 16 Aug 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007458073 | English | London, United Kingdom Shrapnel (G1) - Transformers Wiki I removed a huge chunk of shrapnel from his shoulder. Before we reassemble we got to find the bomb parts first, which means we need to pick out every piece of shrapnel from all the debris collected at the scene. Shrapnel from an IED. They didn't find any meteor rock in his system, But they did find metal shrapnel from the barrels. Shrapnel from the shell hit and pierced the roof of a prefabricated cabin at that position. Well, Demir Malki was hit with shrapnel from the blast. The blast of energy was so powerful that it sent the Insecticons fleeing in terror. Super Robot Lifeform Transformers 3. The three Insecticons were among Decepticon forces who formed an alliance with the Autobots during a Martian invasion. They saved Ironhide and Jazz from some of the Martians' giant ants. Mars Attacks: The Transformers. In Primax In an unstable amalgam universe created by the machinations of Sideways and Gong , Shrapnel was one of the many Decepticons who assaulted Guardian City in the year He was soon shot down by Leader-1 when the Guardian leader arrived. After history blipped again to include both Decepticons and Renegades , the Shrapnel and Kickback dumped out of Astrotrain were replaced by Screw Head and Crain Brain as the wounded villains reformatted by Unicron into the Sweeps. Echoes and Fragments. In an alternate timeline where Optimus Prime killed Megatron in the Battle of Autobot City , Shrapnel was damaged during the conflict and was thrown out of Astrotrain with other weakened Decepticons in the aftermath of the battle. -

An Alien Invasion Had Actually Begun

THE DRAMA OF CHRISTMAS THE PLOT On October 30, 1938, the Mercury Theater of Orsen Wells, broadcast a radio play, “The War of the Worlds.” The play was about Martians invading planet earth. It included fictional news reports describing the invasion. Many of the radio listeners who tuned in after the play began, thought the reports were real, and that an alien invasion had actually begun. A nationwide scare and panic ensued. In many big cities, hysteria was evident in the streets. The event became infamous. No one thought it could happen again, but it did… In September 1996 a television newscaster broke into normal programming with footage of an alien space craft hovering over New York City. A White House press conference on the invasion followed. The supposed news report was actually an advertisement for the Spanish release of the film “Independence Day”… Yet hundreds of alarmed and panicked people swamped the station’s switchboards. Twice, bogus reports of an extraterrestrial invasion have created fear and widespread panic among very gullible human beings… Isn’t it ironic that the one real alien invasion of planet earth was barely noticed? On that first Christmas an other-worldly being visited our planet. The one true God, Creator of heaven and earth, !1 landed on the third rock! Immanuel touched down in a village called “Bethlehem.” God was with us! But outside of a few cows, sheep, and shepherds no one else that night was aware the invasion had taken place. Light from another world shined in our darkness. God’s Christmas drama has a plot popular among movies and TV programs today - an alien invasion. -

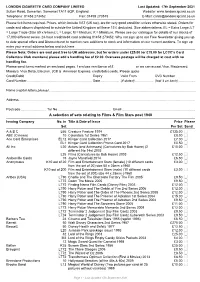

LCCC Thematic List

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Released 25Th September 2019 BOOM! STUDIOS JUL198679

Released 25th September 2019 BOOM! STUDIOS JUL198679 ANGEL #4 (2ND PTG) JUL198681 ANGEL #5 15 COPY FOC SLINEY INCV JUL191315 ANGEL #5 CVR A MAIN PANOSIAN JUL191316 ANGEL #5 CVR B MATTHEWS CONNECTING VAR JUL191317 ANGEL #5 CVR C PREORDER BUONCRISTIANO JUL198680 ANGEL #5 FOC SLINEY INCV JUL191320 ANGEL TP VOL 01 JUN191301 AVANT-GUARDS #8 (OF 8) CVR A MAIN HAYES JUN191302 AVANT-GUARDS #8 (OF 8) CVR B PREORDER MCGEE VAR JUL191339 FAITHLESS #6 (OF 6) CVR A POPE JUL191340 FAITHLESS #6 (OF 6) CVR B EROTICA LOTAY VAR JUL198682 FAITHLESS #6 (OF 6) FOC LEE VAR JUL198685 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #1 25 COPY TONG VAR JUL198684 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #1 BLANK SKETCH VAR JUL191302 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #1 CVR A JUL191303 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #1 CVR B CONNECTING VAR JUL198683 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #1 FOC WARD VAR MAY191240 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL CREATION MYTHS COMPLETE HC JUL191344 LUMBERJANES #66 CVR A LEYH JUL191345 LUMBERJANES #66 CVR B PREORDER MILLEDGE VAR JUL191331 MIGHTY MORPHIN POWER RANGERS #43 CVR A CAMPBELL JUL198687 MIGHTY MORPHIN POWER RANGERS #43 FOC MORA VAR JUL191333 MIGHTY MORPHIN POWER RANGERS #43 FOIL MONTES VAR DARK HORSE COMICS MAY190279 ALIENS RESCUE #3 (OF 4) CVR A DE LA TORRE MAY190280 ALIENS RESCUE #3 (OF 4) CVR B CHATER MAY190278 ART OF RAGE 2 HC MAY190290 BERSERK TP VOL 40 MAY190263 DISNEY CHRISTMAS CAROL STARRING SCROOGE MCDUCK TP JUN190366 DISNEY FROZEN HERO WITHIN #3 (OF 3) KAWAII CREATIVE STUDIO MAY190295 ELFEN LIED OMNIBUS TP VOL 02 JUL190364 -

Shrapnel Ebook, Epub

SHRAPNEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Wharton | 272 pages | 16 Aug 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007458073 | English | London, United Kingdom Shrapnel PDF Book Conflagration Shrapnel was also present at Tyger Pax during the aborted peace treaty between the Autobots, Decepticons, and Ultracons. Which disembodied AI would you use as a personal assistant? Facebook Twitter. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica Encyclopaedia Britannica's editors oversee subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge, whether from years of experience gained by working on that content or via study for an advanced degree Target Shrapnel arrived on Earth to play a key role in the Hoover Dam battle, and afterwards served on Earth under Megatron permanently Aerialbots over America! Choose a dictionary. This leads to nothing more for the Decepticons but being sprayed by Ironhide's acid-dispenser, forcing the lot of them to retreat. As a being made of organic metal, Shrapnel has superhuman strength and stamina. The Beast Within Part 2, Consequences. He was spectator to Megatron and Optimus having a fateful duel, which left both faction leaders badly damaged. Shrapnel may have been killed by the Underbase -powered Starscream , or alternatively he could've just been really lazy and not gotten involved with things—he's one of Cybertron's deadliest killers, what does he have to prove? One time Slag sucker-punched him so hard, Shrapnel's colors went wrong. Power of the Primes Skrapnel packaging bio. You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics: Small amounts of money. Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Apr COF C1:Customer 3/8/2012 3:24 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18APR 2012 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG IFC Darkhorse Drusilla:Layout 1 3/8/2012 12:24 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page April:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/8/2012 11:16 AM Page 1 THE MASSIVE #1 STAR WARS: KNIGHT DARK HORSE COMICS ERRANT— ESCAPE #1 (OF 5) DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: MINUTEMEN #1 DC COMICS MARS ATTACKS #1 IDW PUBLISHING AMERICAN VAMPIRE: LORD OF NIGHTMARES #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO PLANETOID #1 IMAGE COMICS SPAWN #220 SPIDER-MEN #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/8/2012 11:40 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strawberry Shortcake Volume 2 #1 G APE ENTERTAINMENT The Art of Betty and Veronica HC G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Bleeding Cool Magazine #0 G BLEEDING COOL 1 Radioactive Man: The Radioactive Repository HC G BONGO COMICS Prophecy #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Pantha #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Power Rangers Super Samurai Volume 1: Memory Short G NBM/PAPERCUTZ Bad Medicine #1 G ONI PRESS Atomic Robo and the Flying She-Devils of the Pacific #1 G RED 5 COMICS Alien: The Illustrated Story Artist‘s Edition HC G TITAN BOOKS Alien: The Illustrated Story TP G TITAN BOOKS The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen III: Century #3: 2009 G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Harbinger #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Winx Club Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA BOOKS & MAGAZINES Flesk Prime HC G ART BOOKS DC Chess Figurine Collection Magazine Special #1: Batman and The Joker G COMICS Amazing Spider-Man Kit G COMICS Superman: The High Flying History of America‘s Most Enduring -

Or Live Online Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook and Twitter @Back2past for Updates

2/26 - Cooler Than Cool: Classic Comics & Toys 2/26/2020 This session will be held at 6PM, so join us in the showroom (35045 Plymouth Road, Livonia MI 48150) or live online via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! (Showroom Terms: No buyer's premium!) Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast (See site for terms) LOT # LOT # 1 Auctioneer Announcements 12 Group of (5) Modern Notable Books Assortment may include semi-key issues, variants or 2 Tomb Raider #1 CGC 9.6/Key 1st Lara Croft in her own title. CGC graded comic. classic covers. Most are in VF/VF+ condition. You get all that is pictured. 3 Group of (5) Modern Notable Books Assortment may include semi-key issues, variants or 13 New Mutants #100/1991/1st X-Force classic covers. Most are in VF/VF+ condition. You get NM condition. all that is pictured. 14 Grimm Fairy Tales 2008 Annual/Pin-Up NM condition. 4 Batman Lost #1/2018/Dark Nights Metal NM condition. 15 Group of (5) Modern Notable Books Assortment may include semi-key issues, variants or 5 Dark Knights Rising #1/Dark Nights Metal NM condition. classic covers. Most are in VF/VF+ condition. You get all that is pictured. 5a Star Trek Autographed Action Figure Jadzia Dax figure, convention signed by actress Terry 15a Wizard of Oz 50th Anniversary Toy Lot Farrell. This does not come with a COA, but Back to Windups made in 1988. -

Sep CUSTOMER ORDER FORM

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 FeB 2013 Sep COMIC THE SHOP’S pISpISRReeVV eeWW CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Sep13 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/8/2013 9:49:07 AM Available only DOCTOR WHO: “THE NAME OF from your local THE DOCTOR” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! GODZILLA: “KING OF THANOS: THE SIMPSONS: THE MONSTERS” “INFINITY INDEED” “COMIC BOOK GUY GREEN T-SHIRT BLACK T-SHIRT COVER” BLUE T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 9 Sep 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 8/8/2013 9:54:50 AM Sledgehammer ’44: blaCk SCienCe #1 lightning War #1 image ComiCS dark horSe ComiCS harleY QUinn #0 dC ComiCS Star WarS: Umbral #1 daWn of the Jedi— image ComiCS forCe War #1 dark horSe ComiCS Wraith: WelCome to ChriStmaSland #1 idW PUbliShing BATMAN #25 CATAClYSm: the dC ComiCS ULTIMATES’ laSt STAND #1 marvel ComiCS Sept13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/8/2013 2:53:56 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Shifter Volume 1 HC l AnomAly Productions llc The Joyners In 3D HC l ArchAiA EntErtAinmEnt llc All-New Soulfire #1 l AsPEn mlt inc Caligula Volume 2 TP l AvAtAr PrEss inc Shahrazad #1 l Big dog ink Protocol #1 l Boom! studios Adventure Time Original Graphic Novel Volume 2: Pixel Princesses l Boom! studios 1 Ash & the Army of Darkness #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt 1 Noir #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt Legends of Red Sonja #1 l d. E./dynAmitE EntErtAinmEnt Maria M. -

Customer Order Form

#380/381 MAY/JUNE20 Name: PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE JUNE 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Cover COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 1:41:01 PM FirstSecondAd.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:49:06 PM PREMIER COMICS BIG GIRLS #1 IMAGE COMICS LOST SOLDIERS #1 IMAGE COMICS RICK AND MORTY CHARACTER GUIDE HC DARK HORSE COMICS DADDY DAUGHTER DAY HC DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: THREE JOKERS #1 DC COMICS SWAMP THING: TWIN BRANCHES TP DC COMICS TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: THE LAST RONIN #1 IDW PUBLISHING LOCKE & KEY: …IN PALE BATTALIONS GO… #1 IDW PUBLISHING FANTASTIC FOUR: ANTITHESIS #1 MARVEL COMICS MARS ATTACKS RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SEVEN SECRETS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS MayJune20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:41:00 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Cimmerian: The People of the Black Circle #1 l ABLAZE 1 Sunlight GN l CLOVER PRESS, LLC The Cloven Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS The Big Tease: The Art of Bruce Timm SC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Totally Turtles Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS 1 Heavy Metal #300 l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist l HERMES PRESS Titan SC l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: Mistress of Chaos TP l PANINI UK LTD Kerry and the Knight of the Forest GN/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC Masterpieces of Fantasy Art HC l TASCHEN AMERICA Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics Hc Gn l TEN SPEED PRESS Horizon: Zero Dawn #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2019 #9 l TITAN COMICS Negalyod: The God Network HC l TITAN COMICS Star Wars: The Mandalorian: