Cardboard Kingdoms Raymond P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) Online

Ch0XW [Mobile pdf] The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) Online [Ch0XW.ebook] The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) Pdf Free Leslie Charteris ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2154235 in Books 2014-06-24 2014-06-24Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.25 x 1.00 x 5.50l, .0 #File Name: 1477843078256 pages | File size: 54.Mb Leslie Charteris : The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. What a Fabulous Adventure!By Carol KiekowThis book is another entertaining adventure of The Saint. I was on the edge of my seat throughout. I heartily recommend it!0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Good "Saint" storyBy Carolyn GravesGood "Saint" story. Location as much a character as the people. Kept my interest and kept me guessing throughout.4 of 13 people found the following review helpful. Super ReaderBy averageSimon Templar is in France, and has an incident on the road with a young woman. He ends up at a small local vineyard that is in financial trouble. The girl, Mimette requests his help. There is a family struggle over the place, and an uncle trying to find an old obscure Templar treasure on the property.Violence ensues, and the treasure is not what anyone thinks. Simon Templar is taking a leisurely drive though the French countryside when he picks up a couple of hitchhikers who are going to work at Chateau Ingare, a small vineyard on the site of a former stronghold of the Knights Templar. -

Zpsl!Ujnft!Cftu!Tfmmfs!Mjtu

Uif!Ofx!Zpsl!Ujnft!Cftu!Tfmmfs!Mjtu This September 10, 1961 Last Weeks Week Fiction Week On List 1 THE AGONY AND THE ECSTASY, by Irving Stone. (Doubleday and Company.) 1 24 2 TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, by Harper Lee. (J.B. Lippincott Company.) 2 58 3 MILA 18, by Leon Uris. (Doubleday and Company.) 3 13 4 THE EDGE OF SADNESS, by Edwin O'Connor. (Little, Brown and Company.) 4 12 5 THE WINTER OF OUR DISCONTENT, by John Steinbeck. (Viking Press.) 5 10 6 THE CARPETBAGGERS, by Harold Robbins. (Trident Press.) 6 11 7 TROPIC OF CANCER, by Henry Miller. (Grove Press.) 7 11 8 REMBRANDT, by Gladys Schmitt. (Random House.) 8 8 9 THE INCREDIBLE JOURNEY, by Sheila Burnford. (Little, Brown and Company.) 10 15 10 CLOCK WITHOUT HANDS, by Carson McCullers. (Houghton Mifflin Company.) 15 2 11 HAWAII, by James A. Michener. (Random House.) 14 94 12 MOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS, by Evan Hunter. (Simon and Schuster.) 9 13 13 MASTER OF THIS VESSEL, by Gwyn Griffin. (Holt Rinehart Winston.) 11 2 14 A JOURNEY TO MATECUMBE, by Robert Lewis Taylor. (McGraw-Hill.) 12 16 15 A MAN IN A MIRROR, by Richard Llewellyn. (Doubleday and Company.) -- 1 16 THE LAST OF THE JUST, by Andre Schwarz-Bart. (Atheneum.) 13 43 Hawes Publications www.hawes.com Uif!Ofx!Zpsl!Ujnft!Cftu!Tfmmfs!Mjtu This September 10, 1961 Last Weeks Week Non-Fiction Week On List 1 THE MAKING OF THE PRESIDENT 1960, by Theodore H. White. (Atheneum.) 2 9 THE RISE AND FALL OF THE THIRD REICH, by William L. -

Read Book the Saint Returns

THE SAINT RETURNS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Leslie Charteris | 212 pages | 24 Jun 2014 | Amazon Publishing | 9781477842980 | English | Seattle, United States The Saint Returns PDF Book Create outlines for what you want to be accomplished. This was scrapped, and Ian Ogilvy took over the halo for 24 episodes as Simon Templar. This amount is subject to change until you make payment. He also somewhat deplored the tendency for the Saint to be seen primarily as a detective, and this was even stated in some of the later stories, e. Reading about Charteris' "amiable rascal" is infinitely easier and much more relaxing than writing more stories about my own fictitious rascal, Misfit Lil whom I like to think shares a trait or two with Mr Simon Templar! Honestly it was probably the highlight of an episode that mostly spun its wheels. Alyssa Milano legs boots feet Chad Allen magazine pin up clipping. Balthazar Getty Alyssa Milano magazine clipping pin up s vintage. He steals from rich criminals and keeps the loot for himself usually in such a way as to put the rich criminals behind bars. He threatens the biggest explosion of all unless sculptress Lynn Jackson is Hell In order for Eugene and Hitler to get out of hell, Eugene has to overcome the thing that has been keeping him in Hell. Simon Templar 24 episodes, The Saint also ventured into the comics section of our newspapers, battling alongside Dick Tracy and the other Sunday heroes. Seller's other items. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. -

The Inventory of the Leslie Charteris Collection

The Inventory of the Leslie Charteris Collection #39 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center charteris.inv CHARTERIS, LESLIE (1907-1993) Addenda, July 1972 - 1993 [13 Paige boxes, Location: SB2G] I. MANUSCRIPTS Box 1 Scripts bound. "The Saint Show." Volumes 1-12. Radio scripts, 1945-1948. "The Fairy Tale Murder." n.d. "Lady on a Train." Film script, 1943. "Two Smart People" by LC and Ethel Hill, 1944. Box 2 "Return of the Saint" TV Series. 1970s. "Appointment in Florence" "Armageddon Alternative" "The Arrangement" "Assault Force" "The Debt Collectors" "The Diplomats Daughter" "Double Take" "Dragonseed" "Duel in Venice" "The Imprudent Professor" "The Judas Game" "Lady on a Train" 1 "The Murder Cartel" "The Nightmare Man" "The Obono Affair" "One Black September" "The Organisation Man" "The Poppy Chain" Box 2 "Prince of Darkness" "The Roman Touch" "Tower Bridge is Falling Down" "Vanishing Point" Part 1 The Salamander Part 2 The Sixth Man "Vicious Circle" "The Village that Sold Its Soul" "Yesterday's Hero" "The Saint" series, 1989. "The Big Bang" "The Blue Dulac" "The Brazilian Connection" "The Software Murders" Synopses for "Saint" scripts with reply 1972, 3 1973, 2 1974, 6 1975, 5 1976, 3 1977, 3 1978, 1 1979, 8 1980, 6 1981, 7 2 1982, 7 1983, 6 1984, 4 1985, 3 1986, 1 1987, 1 1988, 1 Synopses without reply 1962, 1 1971, 1 1973, 3 1974, 1 1977, 1 1978, 2 1981, 1 1983, 5 1984, 6 1987, 1 Eight undated Synopses Box 3 Radio scripts (unbound):#16, 28, 33, 37, 38, 41, 43, 45, 46, and two without numbers. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

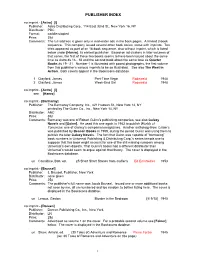

Publisher Index

PUBLISHER INDEX no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] Publisher: Astro Distributing Corp., 114 East 32nd St., New York 16, NY Distributor: PDC Format: saddle-stapled Price: 35¢ Comments: The full address is given only in mail-order ads in the back pages. A limited 2-book sequence. This company issued several other book series, some with imprints. Ten titles appeared as part of an 18-book sequence, also without imprint, which is listed below under [Hanro], its earliest publisher. Based on ad clusters in later volumes of that series, the first of these two books seems to have been issued about the same time as Astro #s 16 - 18 and the second book about the same time as Quarter Books #s 19 - 21. Number 1 is illustrated with posed photographs, the first volume from this publisher’s various imprints to be so illustrated. See also The West in Action. Both covers appear in the Bookscans database. 1 Clayford, James Part-Time Virgin Rodewald 1948 2 Clayford, James W eek -End Girl Rodewald 1948 no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] see [Hanro] no imprint - [Barmaray] Publisher: The Barmaray Company, Inc., 421 Hudson St., New York 14, NY printed by The Guinn Co., Inc., New York 14, NY Distributor: ANC Price: 35¢ Comments: Barmaray was one of Robert Guinn’s publishing companies; see also Galaxy Novels and [Guinn]. He used this one again in 1963 to publish Worlds of Tomorrow, one of Galaxy’s companion magazines. Another anthology from Collier’ s was published by Beacon Books in 1959, during the period Guinn was using them to publish the later Galaxy Novels. -

P R O S P E C T

PROSPECTUS CHRIS ABANI EDWARD ABBEY ABIGAIL ADAMS HENRY ADAMS JOHN ADAMS LÉONIE ADAMS JANE ADDAMS RENATA ADLER JAMES AGEE CONRAD AIKEN DANIEL ALARCÓN EDWARD ALBEE LOUISA MAY ALCOTT SHERMAN ALEXIE HORATIO ALGER JR. NELSON ALGREN ISABEL ALLENDE DOROTHY ALLISON JULIA ALVAREZ A.R. AMMONS RUDOLFO ANAYA SHERWOOD ANDERSON MAYA ANGELOU JOHN ASHBERY ISAAC ASIMOV JOHN JAMES AUDUBON JOSEPH AUSLANDER PAUL AUSTER MARY AUSTIN JAMES BALDWIN TONI CADE BAMBARA AMIRI BARAKA ANDREA BARRETT JOHN BARTH DONALD BARTHELME WILLIAM BARTRAM KATHARINE LEE BATES L. FRANK BAUM ANN BEATTIE HARRIET BEECHER STOWE SAUL BELLOW AMBROSE BIERCE ELIZABETH BISHOP HAROLD BLOOM JUDY BLUME LOUISE BOGAN JANE BOWLES PAUL BOWLES T. C. BOYLE RAY BRADBURY WILLIAM BRADFORD ANNE BRADSTREET NORMAN BRIDWELL JOSEPH BRODSKY LOUIS BROMFIELD GERALDINE BROOKS GWENDOLYN BROOKS CHARLES BROCKDEN BROWN DEE BROWN MARGARET WISE BROWN STERLING A. BROWN WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT PEARL S. BUCK EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS OCTAVIA BUTLER ROBERT OLEN BUTLER TRUMAN CAPOTE ERIC CARLE RACHEL CARSON RAYMOND CARVER JOHN CASEY ANA CASTILLO WILLA CATHER MICHAEL CHABON RAYMOND CHANDLER JOHN CHEEVER MARY CHESNUT CHARLES W. CHESNUTT KATE CHOPIN SANDRA CISNEROS BEVERLY CLEARY BILLY COLLINS INA COOLBRITH JAMES FENIMORE COOPER HART CRANE STEPHEN CRANE ROBERT CREELEY VÍCTOR HERNÁNDEZ CRUZ COUNTEE CULLEN E.E. CUMMINGS MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM RICHARD HENRY DANA JR. EDWIDGE DANTICAT REBECCA HARDING DAVIS HAROLD L. DAVIS SAMUEL R. DELANY DON DELILLO TOMIE DEPAOLA PETE DEXTER JUNOT DÍAZ PHILIP K. DICK JAMES DICKEY EMILY DICKINSON JOAN DIDION ANNIE DILLARD W.S. DI PIERO E.L. DOCTOROW IVAN DOIG H.D. (HILDA DOOLITTLE) JOHN DOS PASSOS FREDERICK DOUGLASSOur THEODORE Mission DREISER ALLEN DRURY W.E.B. -

Ridgefield Encyclopedia (5-15-2020)

A compendium of more than 3,500 people, places and things relating to Ridgefield, Connecticut. by Jack Sanders [Note: Abbreviations and sources are explained at the end of the document. This work is being constantly expanded and revised; this version was last updated on 5-15-2020.] A A&P: The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company opened a small grocery store at 378 Main Street in 1948 (long after liquor store — q.v.); became a supermarket at 46 Danbury Road in 1962 (now Walgreens site); closed November 1981. [JFS] A&P Liquor Store: Opened at 133½ Main Street Sept. 12, 1935. [P9/12/1935] Aaron’s Court: short, dead-end road serving 9 of 10 lots at 45 acre subdivision on the east side of Ridgebury Road by Lewis and Barry Finch, father-son, who had in 1980 proposed a corporate park here; named for Aaron Turner (q.v.), circus owner, who was born nearby. [RN] A Better Chance (ABC) is Ridgefield chapter of a national organization that sponsors talented, motivated children from inner-cities to attend RHS; students live at 32 Fairview Avenue; program began 1987. A Birdseye View: Column in Ridgefield Press for many years, written by Duncan Smith (q.v.) Abbe family: Lived on West Lane and West Mountain, 1935-36: James E. Abbe, noted photographer of celebrities, his wife, Polly Shorrock Abbe, and their three children Patience, Richard and John; the children became national celebrities when their 1936 book, “Around the World in Eleven Years.” written mostly by Patience, 11, became a bestseller. [WWW] Abbot, Dr. -

The Saint Club Merchandise September 2002

The Saint Club Merchandise September 2002 The Saint Club, London www.saint.org The Saint: The Official 2003 Calendar Published by Slow Dazzle Worldwide Ltd. and with exclusive input from Ian Dickerson as well as access to the Carlton archives, this is a unique publication that every fan of the work of Simon Templar and the adventures of Leslie Charteris will want on their wall. Available from The Saint Club cheaper then you’ll find it in the High Street (least if you’re in the UK)! UK: £8.99 Europe: £10.49 North America: $15.99 Rest of World: £11.49 DVD: The Saint and the Fiction Makers (region 2) With Carlton progressively less interested in issuing region 2 Saint DVDs French company PVB Editions has taken up the challenge and issued a collectors edition of The Saint and the Fiction Makers on DVD. This is a two disc set featuring a version of the movie dubbed into French and a version of the movie in English with French subtitles. Plus lots of extras from ITC expert Jaz Wiseman, Saint webmaster Dan Bodenheimer…and some guy called Dickerson. Available for sale in France, Belgium and Switzerland, The Saint Club is the only place in the UK to offer The Fiction Makers on DVD. UK: £14.99 Europe: £15.99 North America: $28.99 Rest of World: £16.99 A Slight Hangover is former TV Saint Ian Ogilvy's third book and was published by Writers Club Press in 2000. "A Slight Hangover is a funny and affectionate look at three generations of clever, witty and thoroughly immoral people. -

The Ridpath Library of Universal Literature in 25 Volumes by John Clark Ridpath Published by Globe, New York, 1899 Biographical

The Ridpath Library of Universal Literature in 25 Volumes By John Clark Ridpath Published by Globe, New York, 1899 Biographical and bibliographical summary of the world's most eminent authors $65.00 The Works of Charles Dickens in 36 Volumes Published by Scribner's Sons, New York, 1911 A nice set of Dickens' works $90.00 The Writings of Mark Twain in 25 Volumes Authorized Uniform Edition Published by P. F. Collier & Son, 1922 $75.00 Die Insel Berlin - ein Bildbericht By Arno Scholz and Peter K. Orton Published by Arani Verkags, Berlin 1955 Signed by one of the authors $10.00 Interview with the Vampire By Anne Rice Published by Alfred A. Knopf, 1976 Stated First Edition Dust jacket flap $8.95 $30.00 Locomotives and Locomotive Building in America Illustrated Catalogue Published by Howell-North Books, 1963 A Limited Edition of 1250 copies of which this is number 297 Hardcover with clear wrap, clean. $12.00 Gaslight Square An Oral History by Thomas Crone Published by The William and Joseph Press, 2004 Hardcover with dust jacket, nice condition. $25.00 Grzyby Srodkowej Europy (Mushrooms of Central Europe) by M. Scrcek B. Vancura Published by Panstweowe 1987 The book includes theoretical knowledge about mushrooms: their structure, biology, the importance of the environment; discussion of poisonous mushrooms and mushroom poisoning, ways of collecting mushrooms. Text in Polish. $10.00 There are five hard covers with dust jackets, each in its own slipcase. These are all published by First Edition Library and are excellent facsimiles of the true First Editions. All are in great condition. -

1 Exploring Detective Films in the 1930S and 1940S: Genre, Society and Hollywood

Notes 1 Exploring Detective Films in the 1930s and 1940s: Genre, Society and Hollywood 1. For a discussion of Hollywood’s predilection for action in narratives, see Elsaesser (1981) and the analysis of this essay in Maltby (1995: 352−4). 2. An important strand of recent criticism of literary detective fiction has emphasised the widening of the genre to incorporate female and non-white protagonists (Munt, 1994; Pepper, 2000; Bertens and D’Haen, 2001; Knight, 2004: 162−94) but, despite Hollywood’s use of Asian detectives in the 1930s and 1940s, these accounts are more relevant to contemporary Hollywood crime films. 3. This was not only the case in B- Movies, however, as Warner’s films, includ- ing headliners, in the early 1930s generally came in at only about an hour and one- quarter due to budgetary restraints and pace was a similar neces- sity. See Miller (1973: 4−5). 4. See Palmer (1991: 124) for an alternative view which argues that ‘the crimi- nal mystery dominates each text to the extent that all the events in the narrative contribute to the enigma and its solution by the hero’. 5. Field (2009: 27−8), for example, takes the second position in order to create a binary opposition between the cerebral British whodunnit and the visceral American suspense thriller. 6. The Republic serials were: Dick Tracyy (1937), Dick Tracy Returns (1938), Dick Tracy’s G- Men (1939) and Dick Tracy vs Crime, Inc. (1941) (Langman and Finn, 1995b: 80). 7. The use of the series’ detectives in spy-hunter films after 1941, however, modifies this relationship by giving them at least an ideological affiliation with the discourses of freedom and democracy that Hollywood deploys in its propagandistic representation of the Allies in general and the United States in particular. -

Zpsl!Ujnft!Cftu!Tfmmfs!Mjtu

Uif!Ofx!Zpsl!Ujnft!Cftu!Tfmmfs!Mjtu This June 8 , 1958 Last Weeks Week Fiction Week On List 1 ANATOMY OF A MURDER, by Robert Traver. (St. Martin's.) 1 20 2 THE WINTHROP WOMAN, by Anya Seton. (Houghton Mifflin Company.) 3 14 3 ICE PALACE, by Edna Ferber. (Doubleday.) 2 11 4 A SUMMER PLACE, by Sloan Wilson. (Simon and Schuster, Inc.) 4 7 5 NORTH FROM ROME, by Helen MacInnes. (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.) 5 14 6 THE GREENGAGE SUMMER, by Rumer Godden. (Viking.) 7 9 7 RALLY ROUND THE FLAG BOYS!, by Max Schulman. (Doubleday.) 9 41 8 THE SERGEANT, by Dennis Murphy. (Viking.) 6 10 9 THE MACKEREL PLAZA, by Peter De Vries. ( Little, Brown and Company.) 8 8 10 THE TRAVELS OF JAIMIE McPHEETERS, by Robert Lewis Taylor. (Doubleday.) 10 7 BY LOVE POSSESSED, by James Gould Cozzens. (Harcourt, Brace and 11 12 40 Company.) 12 A DEATH IN THE FAMILY, by James Agee. (McDowell, Obolensky.) 16 12 13 MAGGIE-NOW, by Betty Smith. (Harper and Brothers.) 11 15 14 THE MOUNTAIN ROAD, by Theodore H. White. (William Sloane Associates.) 15 2 15 THE WHITE WITCH, by Elizabeth Goudge. (Coward-McCann, Inc.) 13 20 16 THE UNDERGROUND CITY, by H.L. Humes. (Random House.) -- 2 Hawes Publications www.hawes.com Uif!Ofx!Zpsl!Ujnft!Cftu!Tfmmfs!Mjtu This June 8 , 1958 Last Weeks Week Non-Fiction Week On List 1 MASTERS OF DECEIT, by J. Edgar Hoover. (Henry Holt and Co.) 1 11 2 INSIDE RUSSIA TODAY, by John Gunther. (Harper and Brothers.) 2 7 3 PLEASE DON'T EAT THE DAISIES, by Jean Kerr.