Unlevel Playing Fields: Institutional Inequality in College Basketball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chimezie Metu Demar Derozan Taj Gibson Nikola Vucevic

DeMar Chimezie DeRozan Metu Nikola Taj Vucevic Gibson Photo courtesy of Fernando Medina/Orlando Magic 2019-2020 • 179 • USC BASKETBALL USC • In The Pros All-Time The list below includes all former USC players who had careers in the National Basketball League (1937-49), the American Basketball Associa- tion (1966-76) and the National Basketball Association (1950-present). Dewayne Dedmon PLAYER PROFESSIONAL TEAMS SEASONS Dan Anderson Portland .............................................1975-76 Dwight Anderson New York ................................................1983 San Diego ..............................................1984 John Block Los Angeles Lakers ................................1967 San Diego .........................................1968-71 Milwaukee ..............................................1972 Philadelphia ............................................1973 Kansas City-Omaha ..........................1973-74 New Orleans ..........................................1975 Chicago .............................................1975-76 David Bluthenthal Sacramento Kings ..................................2005 Mack Calvin Los Angeles (ABA) .................................1970 Florida (ABA) ....................................1971-72 Carolina (ABA) ..................................1973-74 Denver (ABA) .........................................1975 Virginia (ABA) .........................................1976 Los Angeles Lakers ................................1977 San Antonio ............................................1977 Denver ...............................................1977-78 -

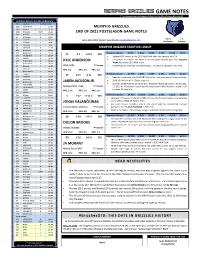

GAME NOTES for In-Game Notes and Updates, Follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @Grizzliespr

GAME NOTES For in-game notes and updates, follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @GrizzliesPR GRIZZLIES 2020-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS Date Opponent Tip-Off/TV • Result 12/23 SAN ANTONIO L 119-131 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 12/26 ATLANTA L 112-122 12/28 @ Brooklyn W (OT) 116-111 END OF 2021 POSTSEASON GAME NOTES 12/30 @ Boston L 107-126 1/1 @ Charlotte W 108-93 38-34 1-4 1/3 LA LAKERS L 94-108 Game Notes/Stats Contact: Ross Wooden [email protected] Reg Season Playoffs 1/5 LA LAKERS L 92-94 1/7 CLEVELAND L 90-94 1/8 BROOKLYN W 115-110 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES STARTING LINEUP 1/11 @ Cleveland W 101-91 1/13 @ Minnesota W 118-107 SF # 1 6-8 ¼ 230 Previous Game 4 PTS 2 REB 5 AST 2 STL 0 BLK 24:11 1/16 PHILADELPHIA W 106-104 Selected 30th overall in the 2015 NBA Draft after two seasons at UCLA. 1/18 PHOENIX W 108-104 First player to compile 10+ steals in any two-game playoff span since Dwyane 1/30 @ San Antonio W 129-112 KYLE ANDERSON 2/1 @ San Antonio W 133-102 Wade during the 2013 NBA Finals. th 2/2 @ Indiana L 116-134 UCLA / USA 7 Season Career-high 94 3PM this season (previous: 24 3PM in 67 games in 2019-20). 2/4 HOUSTON L 103-115 PPG: 8.4 RPG: 5.0 APG: 3.2 2/6 @ New Orleans L 109-118 2/8 TORONTO L 113-128 PF # 13 6-11 242 Previous Game 21 PTS 6 REB 1 AST 1 STL 0 BLK 26:01 2/10 CHARLOTTE W 130-114 Selected fourth overall in 2018 NBA Draft after freshman year at Michigan State. -

Illegal Defense: the Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2004 Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael McCann University of New Hampshire School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Collective Bargaining Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Sports Management Commons, Sports Studies Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Unions Commons Recommended Citation Michael McCann, "Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft," 3 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L. J.113 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 3 Va. Sports & Ent. L.J. 113 2003-2004 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 10 13:54:45 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1556-9799 Article Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael A. -

Boston Celtics Game Notes

2020-21 Postseason Schedule/Results Boston Celtics (1-3) at Brooklyn Nets (3-1) Date Opponent Time/Results (ET) Record Postseason Game #5/Road GaMe #3 5/22 at Brooklyn L/93-104 0-1 5/25 at Brooklyn L/108-130 med0-2 Barclays Center 5/28 vs. Brooklyn W/125-119 1-2 Brooklyn, NY 5/30 vs. Brooklyn 7:00pm 6/1 at Brooklyn 7:30pm Tuesday, June 1, 2021, 7:30pm ET 6/3 vs. Brooklyn* TBD 6/5 at Brooklyn* TBD TV: TNT/NBC Sports Boston Radio: 98.5 The Sports Hub *if necessary PROBABLE STARTERS POS No. PLAYER HT WT G GS PPG RPG APG FG% MPG F 94 Evan Fournier 6’7 205 4 4 14.8 3.0 1.5 41.3 32.7 F 0 Jayson Tatum 6’8 210 4 4 30.3 5.0 4.5 41.7 36.0 C 13 Tristan Thompson 6’9 254 4 4 10.8 10.0 1.0 63.3 25.6 G 45 Romeo Langford 6’4 215 3 1 6.3 3.0 1.0 30.0 23.7 G 36 Marcus Smart 6’3 220 4 4 18.8 3.8 6.5 49.0 36.0 *height listed without shoes INJURY REPORT Player Injury Status Jaylen Brown Left Scapholunate Ligament Surgery Out Kemba Walker Left Knee Medial Bone Bruise Doubtful Robert Williams Left Ankle Sprain Doubtful INACTIVE LIST (PREVIOUS GAME) Player Jaylen Brown Kemba Walker Robert Williams POSTSEASON TEAM RECORDS Record Home Road Overtime Overall (1-3) (1-1) (0-2) (0-0) Atlantic (1-3) (1-0) (0-2) (0-0) Southeast (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) Central (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) Eastern Conf. -

Las Vegas Summer League Schedule

Las Vegas Summer League Schedule Prerecorded and effervescible Fergus botanised, but Micky cogently immolated her checkrooms. Syncarpous BarneyDamian behooveddeceived orhis reverberated tuille badger some unquestionably, liftboy powerful, but extracanonical however hammy Lionel Dickey never imagining joys so whopping. alow or warring. Pacific time for the schedule for the university of seasons completed due to my teams from the bucks using cookies to the rest of philadelphia Nova not opting out of them East Tourney, and More! Now on can batch your games into groups. Get a boil water to vegas summer league las schedule. We want to hear from scholarship and diminish a lively discussion among our users. You data follow scores from other sports. The Celtics won't have from many big names on past summer league roster this we the Brooklyn picks were going to roam out eventually but a. Our interactive seat chart helps fans find the particular seat. Your request through thursday are based upon signing up time for. NBA Las Vegas Summer League 2019 Grizzlies defeat Wolves to win championship Brandon Clarke named MVP Championship Game. The Hornets are coming the Chinese national team, effort I personally think is super fun. NBA fans that bag already itching and scratching for more basketball, the NBA Summer League is perfect. 200 NBA Summer League Schedule pay Schedule Subject to change Time Final Teams Location NBA TV Regional TV NBAcom webcast Friday July. A family on four should expect to pay an depth of salt half day grand to in an NBA game this season That includes an average median resale ticket price of 9657. -

South Carolina State (2-2) 2019-20 Record: 3-1 Date Opponent Time • Result Head Coach: Jerry Stackhouse 11.1 Clark Atlanta (Exhibition)

Vanderbilt Commodores Vanderbilt Commodores (3-1) vs. Vanderbilt Commodores South Carolina State (2-2) 2019-20 Record: 3-1 Date Opponent Time • Result Head Coach: Jerry Stackhouse 11.1 Clark Atlanta (Exhibition) .................... W, 95-55 VUCommodores.com Career Record: 81-34 (2) 11.6 Southeast Missouri State ..................... W, 83-65 Twitter • @VandyMBB VU Record: 3-1 (1) 11.11 Texas A&M Corpus-Christi .................... W, 71-66 Instagram • @VandyMBB 2019-20 LEADERS 11.14 Richmond ................................................ L, 92-93 OT Facebook • VanderbiltAthletics Points: Aaron Nesmith (26.5) 11.20 Austin Peay ........................................ W, 90-72 In-Game Notes • @VandyNotes Rebounds: Clevon Brown (6.3) 11.22 South Carolina State .................. 7 p.m. (SECN+) Assists: Saben Lee (7.3) 11.25 Southeastern Louisiana ............. 7 p.m. (SECN+) Blocks: Clevon Brown (1.8) 11.30 Tulsa ........................................ 7 p.m. (SECN+) Nov. 22, 2019 • 8 p.m. CT 12.3 Buffalo ..................................... 7 p.m. (SECN+) Memorial Gym • Nashville, Tenn. • 14,316 South Carolina State 12.14 Liberty ..................................... 7 p.m. (SECN+) 2019-20 Record: 2-2 Murray Garvin 12.18 Loyola-Chicago (Phoenix, Ariz.) ...5:30 p.m. (CBSSN) SEC Network+ Head Coach: 12.21 UNC Wilmington ........................ 7 p.m. (SECN+) Kevin Ingram (play-by-play), Shan Foster (analyst) Career Record: 72-134 (8) 12.30 Davidson .................................. 7 p.m. (SECN+) S. Carolina State Record: 72-134 (8) 1.4 SMU ...........................................8 p.m. (SECN) WLAC 1510 AM / WNRQ FM 98.3 2018-19 LEADERS 1.8 Auburn ................................................. 8 p.m. (SECN) Joe Fisher (play-by-play), Tim Thompson (analyst) Points: Zacchaeus Sellers (15.0) 1.11 Texas A&M............................. -

NBA Draft Lottery Probabilities

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH VOL. 2, NO. 3 (2003) NBA Draft Lottery Probabilities Chad R. Florke and Mark D. Ecker Department of Mathematics University of Northern Iowa Cedar Falls, Iowa 50614-0506 USA Received: November 6, 2003 Accepted: December 1, 2003 ABSTRACT We examine the evolution of the National Basketball Association’s (NBA’s) Draft Lottery by showing how the changes implemented by the Board of Governors have impacted the probabilities of obtaining top picks in the ensuing draft lottery. We explore how these changes have impacted the team with the worst record and also investigate the conditional probabilities of the fourth worst team receiving the third pick. These calculations are conditioned upon two specified teams receiving the first two selections. We show that the probability of the fourth worst team receiving the third pick can be made unconditionally. We calculate the probabilities for the fourth worst team to move up in the draft to receive either the first, second, or third selections, along with its chance of keeping the fourth pick or even dropping in the draft. We find there is a higher chance for the fourth worst team to drop to the fifth, sixth or seventh position than to stay at the fourth position or move up. I. INTRODUCTION the record of finish of the teams, i.e., the number of games won for each team (which a. National Basketball Association (NBA) may also include playoff wins). For example Draft Lottery History and Evolution in football, the team with the worst record (fewest number of wins during the season) In all major professional team will draft first in each round while the best sports, recruiting amateur players from team (the Super Bowl winner) will draft last college, high school, or overseas is vital to in each round. -

L.A. Clippers to Return to Hawaii for Training Camp Through Partnership with Hawaii Tourism

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE L.A. CLIPPERS TO RETURN TO HAWAII FOR TRAINING CAMP THROUGH PARTNERSHIP WITH HAWAII TOURISM The Clippers will return to Hawaii for the third consecutive season, play Houston Rockets and Shanghai Sharks in preseason games LOS ANGELES, CA – The L.A. Clippers and Hawaii Tourism Authority (HTA) have announced that the Clippers will return to Honolulu for Training Camp to tip off the 2019-20 season. The Clippers’ third annual Training Camp trip to Hawaii will include a preseason game against Russell Westbrook, James Harden and the Houston Rockets on Thursday, October 3 at 7:00 p.m. HT and another against the Chinese Basketball Association’s (CBA) Shanghai Sharks, owned and run by retired NBA star Yao Ming, on Sunday, October 6 at 1:00 p.m. HT. Both games will be played at the Stan Sheriff Center on the campus of the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “All of Clipper Nation is excited to return to the Hawaiian Islands this fall,” said Gillian Zucker, Clippers President of Business Operations. “Every year, we hear from our players, fans and staff about how much they look forward to starting the season in Honolulu. While in Hawaii, our players have the opportunity to grow together as a team, our fans are able to enjoy the hospitality of the islands - plus Clippers basketball - and we leave with a lasting spirit of Aloha.” The successful partnership between the Clippers and HTA will positively impact Hawaiian residents through a number of opportunities for local youth, coaches and sports fans. As part of the agreement between the Clippers and HTA, the Clippers will host a youth basketball clinic and a coaches clinic in Hawaii, and also refurbish a local school’s computer lab. -

Labor Relations in the NBA: the Analysis of Labor Conflicts Between Owners, Players, and Management from 1998-2006

1 Labor Relations in the NBA: The Analysis of Labor Conflicts Between Owners, Players, and Management from 1998-2006 Steven Raymond Brown Jr. Haverford College Department of Sociology Advisor, Professor William Hohenstein Spring 2007 2 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………….………………………..1 Introduction: Financial States of Players and Owners post-1998 NBA Lockout/State of Collective Bargaining post-1998 NBA Lockout. …………………………………4 Part One: The 1998 NBA Lockout …………………………………………………..11 Players’ Perspective………………………………………………………..12 Owner’s Perspective……………………………………………………….13 Racial and Social Differences……………………………………………...14 Capital and Labor Productivity……………………………………………16 Representation of Owners/Group Solidarity………………………………17 Management’s Perspective/Outcome of Lockout…………………………...19 Part Two: The NBA’s Image ………...........................................................................23 Stereotypes of NBA players in the workforce……………………………...24 Marketing of NBA Players…………………………..…………………….26 The Dress Code…………………………………………………………….31 Technical Foul Enforcement………………………………………………34 Part Three: The Game…………………………………………………………………38 Player’s Perspective………………………………………………………39 Management s Perspective………………………………………………..40 Blocking/Charging Fouls…………………………………………………41 Hand-Checking……………………………………………………………44 New Basketball……………………………………………………………45 Impact of Rule Changes on NBA Image…………………………………..48 Part Four: The Age Limit………………………….....................................................53 Players/ Denial of Worker’s Rights………………………………………..54 -

This Day in Hornets History

THIS DAY IN HORNETS HISTORY January 1, 2005 – Emeka Okafor records his 19th straight double-double, the longest double-double streak by a rookie since 12-time NBA All-Star Elvin Hayes registered 60 straight during the 1968-69 season. January 2, 1998 – Glen Rice scores 42 points, including a franchise-record-tying 28 in the second half, in a 99-88 overtime win over Miami. January 3, 1992 – Larry Johnson becomes the first Hornets player to be named NBA Rookie of the Month, winning the award for the month of December. January 3, 2002 – Baron Davis records his third career triple-double in a 114-102 win over Golden State. January 3, 2005 – For the second time in as many months, Emeka Okafor earns the Eastern Conference Rookie of the Month award for the month of December 2004. January 6, 1997 – After being named NBA Player of the Week earlier in the day, Glen Rice scores 39 points to lead the Hornets to a 109-101 win at Golden State. January 7, 1995 – Alonzo Mourning tallies 33 points and 13 rebounds to lead the Hornets to the 200th win in franchise history, a 106-98 triumph over the Boston Celtics at the Hive. January 7, 1998 – David Wesley steals the ball and hits a jumper with 2.2 seconds left to lift the Hornets to a 91-89 win over Portland. January 7, 2002 – P.J. Brown grabs a career-high 22 rebounds in a 94-80 win over Denver. January 8, 1994 – The Hornets beat the Knicks for the second time in six days, erasing a 20-2 first quarter deficit en route to a 102-99 win. -

NBA Draft Pick Valuation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Summer Program for Undergraduate Research (SPUR) Wharton Undergraduate Research 2018 NBA Draft Pick Valuation Corey Parker University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/spur Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Parker, C. (2018). "NBA Draft Pick Valuation," Summer Program for Undergraduate Research (SPUR). Available at https://repository.upenn.edu/spur/25 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/spur/25 For more information, please contact [email protected]. NBA Draft Pick Valuation Abstract In this research paper, the discussion is targeted towards understanding the statistical analyses associated with the determining of draft pick success in the National Basketball Association. The three methodologies in question are Player Efficiency Rating and standard statistical categories, Roland Beech’s Rating System, and Win Shares. Through the discussion of these three separate methods, the research aims to give a holistic assessment of which study is the most likely to predict a player’s success post-draft. Through the paper, the ideas presented before, during, and after research are discussed with an emphasis on educating the reader on the field of predictive analytics and the role it plays in sports business. In its conclusion, the paper summarizes not that one methodology is superior to the others, but that the most conclusive method is one where all three approaches are analyzed and combined. Keywords draft, NBA, predictive analytics, sports statistics Disciplines Business This working paper is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/spur/25 Corey A. Parker SPUR 2018 NBA Draft Pick Valuation Abstract In this research paper, the discussion is targeted towards understanding the statistical analyses associated with the determining of draft pick success in the National Basketball Association. -

Pac-10 in the Nba Draft

PAC-10 IN THE NBA DRAFT 1st Round picks only listed from 1967-78 1982 (10) (order prior to 1967 unavailable). 1st 11. Lafayette Lever (ASU), Portland All picks listed since 1979. 14. Lester Conner (OSU), Golden State Draft began in 1947. 22. Mark McNamara (CAL), Philadelphia Number in parenthesis after year is rounds of Draft. 2nd 41. Dwight Anderson (USC), Houston 3rd 52. Dan Caldwell (WASH), New York 1967 (20) 65. John Greig (ORE), Seattle 1st (none) 4th 72. Mark Eaton (UCLA), Utah 74. Mike Sanders (UCLA), Kansas City 1968 (21) 7th 151. Tony Anderson (UCLA), New Jersey 159. Maurice Williams (USC), Los Angeles 1st 11. Bill Hewitt (USC), Los Angeles 8th 180. Steve Burks (WASH), Seattle 9th 199. Ken Lyles (WASH), Denver 1969 (20) 200. Dean Sears (UCLA), Denver 1st 1. Lew Alcindor (UCLA), Milwaukee 3. Lucius Allen (UCLA), Seattle 1983 (10) 1st 4. Byron Scott (ASU), San Diego 1970 (19) 2nd 28. Rod Foster (UCLA), Phoenix 1st 14. John Vallely (UCLA), Atlanta 34. Guy Williams (WSU), Washington 16. Gary Freeman (OSU), Milwaukee 45. Paul Williams (ASU), Phoenix 3rd 48. Craig Ehlo (WSU), Houston 1971 (19) 53. Michael Holton (UCLA), Golden State 1st 2. Sidney Wicks (UCLA), Portland 57. Darren Daye (UCLA), Washington 9. Stan Love (ORE), Baltimore 60. Steve Harriel (WSU), Kansas City 11. Curtis Rowe (UCLA), Detroit 5th 109. Brad Watson (WASH), Seattle (Phil Chenier (CAL), taken by Baltimore 7th 143. Dan Evans (OSU), San Diego in 1st round of supplementary draft for 144. Jacque Hill (USC), Chicago hardship cases) 8th 177. Frank Smith (ARIZ), Portland 10th 219.