Issn 0017-0615 the Gissing Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jennings Ale Alt

jennings 4 day helvellyn ale trail Grade: Time/effort 5, Navigation 3, Technicality 3 Start: Inn on the Lake, Glenridding GR NY386170 Finish: Inn on the Lake, Glenridding GR NY386170 Distance: 31.2 miles (50.2km) Time: 4 days Height gain: 3016m Maps: OS Landranger 90 (1:50 000), OS Explorer OL 4 ,5,6 & 7 (1:25 000), Harveys' Superwalker (1:25 000) Lakeland Central and Lakeland North, British Mountain Maps Lake District (1:40 000) Over four days this mini expedition will take you from the sublime pastoral delights of some of the Lake District’s most beautiful villages and hamlets and to the top of its best loved summits. On the way round you will be rewarded with stunning views of lakes, tarns, crags and ridges that can only be witnessed by those prepared to put the effort in and tread the fell top paths. The journey begins with a stay at the Inn on the Lake, on the pristine shores of Ullswater and heads for Grasmere and the Travellers Rest via an ancient packhorse route. Then it’s onto the Scafell Hotel in Borrowdale via one of the best viewpoint summits in the Lake District. After that comes an intimate tour of Watendlath and the Armboth Fells. Finally, as a fitting finish, the route tops out with a visit to the lofty summit of Helvellyn and heads back to the Inn on the Lake for a well earned pint of Jennings Cocker Hoop or Cumberland Ale. Greenside building, Helvellyn. jennings 4 day helvellyn ale trail Day 1 - inn on the lake, glenridding - the travellers’rest, grasmere After a night at the Inn on the Lake on the shores of Ullswater the day starts with a brief climb past the beautifully situated Lanty’s Tarn, which was created by the Marshall Family of Patterdale Hall in pre-refrigerator days to supply ice for an underground ‘Cold House’ ready for use in the summer months! It then settles into its rhythm by following the ancient packhorse route around the southern edge of the Helvellyn Range via the high pass at Grisedale Hause. -

22 PEAK CHALLENGE 2015 the Challenge

22 PEAK CHALLENGE 2015 The Challenge: We would like to invite you to take part in a mega challenge. The 4 Lakeland 3000’s (AKA 4 highest mountains in England/ Lake District Munro’s) are a challenge in their own right, but we want to throw in an additional 18 summits to make it 22 summits in 3 days. This will mean walking approximately 46 miles and ascending 4,919m/16,138ft! We are hoping we can encourage you to join us on this exciting weekend and be part of a team supporting the vital work that we do here at The Lake District Calvert Trust. This is a challenge not to be underestimated but it is certainly one to be embraced, and the sense of achievement you will feel on completing it will be second to none. If you would like to experience this 3-day adventure and join a team of around 20 people to raise funds for the Lake District Calvert Trust then read on! The Route: The route will start at the Lake District Calvert Trust centre and finish at the Moot Hall in Keswick. Please note the route is subject to change if adverse weather conditions become an issue, but we will endeavour to follow the planned itinerary as closely as possible. The 22 summits included in the walk are as follows: DAY 1 Dodd 491m; Carlside 746m; Skiddaw Little Man 865m; Skiddaw 931m; Clough Head 726m; Great Dodd 857m; Stybarrow Dodd 843m; Raise 883m; White Side 863m; Helvellyn - Lower Man 925m; Helvellyn 950m DAY 2 High Raise 762m; Broad Crag 934m; Scafell Pike 978m; Symonds Knott 959m; Scafell 964m DAY 3 Great Gable 899m; Green Gable 801m; Brandreth 715m; High Spy 653m; Maiden Moor 576m; Catbells 451m For health & safety it will be essential that all walkers stick to the agreed route. -

Lake District Scrambles Striding and Sharp Edges

Scrambles Weekend Details Lake District Scrambles – Helvellyn via Striding Edge General Outline The weekend is a mountain weekend - and incorporates grade 1 scrambling. For some of you this may take you out of your comfort zone, but for most it should just be a rewarding and exciting way to get to the top of a mountain and it should not be a reason to put you off. No technical climbing skills as such are required, and nor is any climbing equipment. For safety reasons, in the event of adverse weather conditions it may be necessary to cancel the scrambling plan and do solely hill- walking instead. Plan Saturday: Striding Edge is a classic scrambling route on Helvellyn, linking the summit ridge of Birkhouse Moor to Helvellyn's summit by what becomes a sharp arête. From Helvellyn we’ll head north and maybe bag a few Wainwrights – Lower Man, White Side, Raise and Stybarrow Dodd before heading off back to the pub! This day is not too much of an expedition so you don’t even have to be a fitness nutcase to enjoy it. On Sunday we'll be driving north to Blencathra where the infamous Sharp Edge awaits. The book describes this one as “Lakeland’s sharpest ridge and justly popular” – a great route to take us to the top of Blencathra! This is indeed another Lake District classic and one not to miss if you’re new to this game of scrambling. And more than that – this way we can also descend down another great route – Halls Fell Ridge - making this a super day out! Meeting time and place Meet up outside the Traveller’s Rest (Greenside Rd, Glenridding, CA11 0QQ) on Saturday morning at 9.30am ready to go. -

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - the Check List Thirty-Six Circular Walks Covering All the Peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - The Check List Thirty-six circular walks covering all the peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells. This list is provided for those of you wishing to complete the Wainwright's in 36 walks. Simply tick off each mountain as completed when the task of climbing it has been accomplished. Mountain Book Walk Completed Arnison Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birkhouse Moor The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birks The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Catstye Cam The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Clough Head The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Dollywaggon Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Dove Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Fairfield The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Glenridding Dodd The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Gowbarrow Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Dodd The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Great Mell Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Rigg The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Side The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Hartsop Above How The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit Helvellyn The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Heron Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Mountain Book Walk Completed High Hartsop Dodd The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit High Pike (Scandale) The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Little Hart Crag -

Bob Graham Detailed Notes

Bob Graham Detailed Notes These notes are intended to provide a short summary of the best line to take in terms of time and effort. The notes are meant to be read in conjunction with the OS Explorer OL series of maps:- OL4, OL5, OL6 & OL7. However there is a new (as of 2005) map at 1:40,000 scale of the whole Lake District on one sheet. The map is produced by the BMC in association with Harveys maps . The map is printed on plastic so it is tear resistant and completely waterproof! Someone at the BMC must have known about the Bob Graham Round as, although the main map finishes just to the north of Skiddaw, Great Calva appears on an “insert” on the back. Grid references are in parentheses and are preceded with GR: (GR123456). Summits are not generally given grid references in these notes. Also some spellings may be different to those in common use: particularly the use of the correct “gill” as opposed to the pretentious “ghyll” introduced by Wordsworth and Southey. Bearings are also in parentheses but are preceded by MB-: ( MB-256 ). All bearings are magnetic rather than grid. The magnetic variation is taken as 3 degrees. If anyone has any corrections or additions to make to these notes then please send them in. There are several points on the round where there are alternative routes. These are indicated by the word (alternative) in the text. Hold your mouse over the word to see the variation. Section Times The table below shows expected times for each section for a number of schedules. -

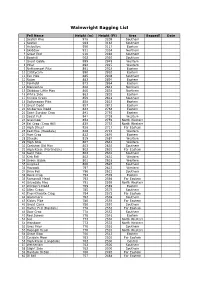

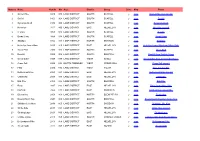

Wainwright Bagging List

Wainwright Bagging List Fell Name Height (m) Height (Ft) Area Bagged? Date 1 Scafell Pike 978 3209 Southern 2 Scafell 964 3163 Southern 3 Helvellyn 950 3117 Eastern 4 Skiddaw 931 3054 Northern 5 Great End 910 2986 Southern 6 Bowfell 902 2959 Southern 7 Great Gable 899 2949 Western 8 Pillar 892 2927 Western 9 Nethermost Pike 891 2923 Eastern 10 Catstycam 890 2920 Eastern 11 Esk Pike 885 2904 Southern 12 Raise 883 2897 Eastern 13 Fairfield 873 2864 Eastern 14 Blencathra 868 2848 Northern 15 Skiddaw Little Man 865 2838 Northern 16 White Side 863 2832 Eastern 17 Crinkle Crags 859 2818 Southern 18 Dollywagon Pike 858 2815 Eastern 19 Great Dodd 857 2812 Eastern 20 Stybarrow Dodd 843 2766 Eastern 21 Saint Sunday Crag 841 2759 Eastern 22 Scoat Fell 841 2759 Western 23 Grasmoor 852 2759 North Western 24 Eel Crag (Crag Hill) 839 2753 North Western 25 High Street 828 2717 Far Eastern 26 Red Pike (Wasdale) 826 2710 Western 27 Hart Crag 822 2697 Eastern 28 Steeple 819 2687 Western 29 High Stile 807 2648 Western 30 Coniston Old Man 803 2635 Southern 31 High Raise (Martindale) 802 2631 Far Eastern 32 Swirl How 802 2631 Southern 33 Kirk Fell 802 2631 Western 34 Green Gable 801 2628 Western 35 Lingmell 800 2625 Southern 36 Haycock 797 2615 Western 37 Brim Fell 796 2612 Southern 38 Dove Crag 792 2598 Eastern 39 Rampsgill Head 792 2598 Far Eastern 40 Grisedale Pike 791 2595 North Western 41 Watson's Dodd 789 2589 Eastern 42 Allen Crags 785 2575 Southern 43 Thornthwaite Crag 784 2572 Far Eastern 44 Glaramara 783 2569 Southern 45 Kidsty Pike 780 2559 Far -

Nutt No Name Nutt Ht Alt Area District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell

Nutt no Name Nutt ht Alt Area District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell Pike 3209 978 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell Pike from Scafell 2 Scafell 3163 964 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell 3 Symonds Knott 3146 959 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Symonds Knott 4 Helvellyn 3117 950 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Helvellyn summit 5 Ill Crag 3068 935 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Ill Crag 6 Broad Crag 3064 934 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Broad Crag 7 Skiddaw 3054 931 LAKE DISTRICT NORTH SKIDDAW y map Skiddaw 8 Helvellyn Lower Man 3035 925 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Helvellyn Lower Man from White Side 9 Great End 2986 910 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Great End 10 Bowfell 2959 902 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH BOWFELL y map Bowfell from Crinkle Crags 11 Great Gable 2949 899 LAKE DISTRICT WEST GABLE y map Great Gable from the Corridor Route 12 Cross Fell 2930 893 NORTH PENNINES WEST CROSS FELL y map Cross Fell summit 13 Pillar 2926 892 LAKE DISTRICT WEST PILLAR y map Pillar from Kirk Fell 14 Nethermost Pike 2923 891 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Nethermost Pike summit 15 Catstycam 2920 890 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Catstycam 16 Esk Pike 2904 885 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH BOWFELL y map Esk Pike 17 Raise 2897 883 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Raise from White Side 18 Fairfield 2864 873 LAKE DISTRICT EAST FAIRFIELD y map Fairfield from Gavel Pike 19 Blencathra 2858 868 LAKE DISTRICT NORTH BLENCATHRA y map Blencathra 20 Bowfell North Top 2841 866 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH BOWFELL y map Bowfell North Top from -

The Near Eastern Fells (434M/1424Ft) the NEAR EASTERN FELLS

FR THE OM GREAT MELL FELL THE FR NEAR W OM LIT TLE MELL FELL EST LIT TLE MELL FELL THE FR OM NORTH EASTERN GOWBARROW FELL THE CLOUGH HEAD (857m/2812ft) GREAT MELL FELL EAST MIDDLE DODD HIGH HARTSOP DODD 11 Great Dodd Great 11 RED SCREES HARTSOP ABOVE HOW LIT TLE HART CRAG GREAT DODD Kir BIRKS FELL kstone WATSON’S DODD RED SCREES Pass ST SUNDAY CRAG STYBARROW DODD MIDDLE DODD S (481m/1578ft) HIGH HARTSOP BIRKHOUSE MOOR DODD FAIRFIELD – DOVE CRAG HART SIDE 10 Gowbarrow Fell Gowbarrow 10 four RAISE HART CRA G CATSTYCAM WHITE SIDE FAIRFIE LD RAISE gr HARTSOP HELVELLYN ABOVE HOW GREAT DODD HELVELLYN aphic LOWER MAN DOLLYWAGGON CLOUGH HEAD PIKE HELVELLYN (442m/1450ft) ST SUNDAY CRAG projections NETHER MOST PIKE NETHERMOST PIKE 9 Glenridding Dodd Glenridding 9 BIRK S ARNISO N CRAG DOLL YWAGGO N PIKE HELVELLYN BIRKHOUSE MOOR A66 CATSTYCAM Dunmail FAIRFIELD of WHITE SIDE FR SEAT SANDAL (873m/2864ft) OM Raise the RAISE DOVE CRAG GLENRID DING THE GREAT RIGG 8 Fairfield 8 DODD SHEFFIELD PIKE HELVELLYN r ange ST YBA S NETHERMOST PIKE RROW OUT DODD DOLLYWAGGON PIKE STONE ARTHUR RED WATSON’S SEAT SANDAL SCREES DODD H HART SIDE FAIRFIELD HERON PIKE GREAT RIG GREAT DODD G HERON PIKE (792m/2599ft) NAB SCAR NAB SCAR HART CRAG 7 Dove Crag Dove 7 DOVE CRAG HIGH PIKE GOWBARROW FELL LOW PIKE CLOUGH HEAD LIT T LE HART CRAG FELL RED SCREES LIT TLE MELL FELL (858m/2815ft) 6 Dollywaggon Pike Dollywaggon 6 ED K L WA E DAT GREAT MELL FELL S E NOT (726m/2386ft) CENTRAL CENTRAL 5 Clough Head Clough 5 FELLS Rydal Rydal Gr asmer Wa km 17 te 1 e r 2 G A RASMER m M 3 (890m/2920ft) -

1. Eastern Fells

1. Eastern Fells Type Direction Distance / km Ascent / m Descent / m Time / h:mm Linear Troutbeck -> Patterdale 77 5045 5164 14:18 Linear Patterdale -> Troutbeck 77 5164 5045 14:23 Circular 82 5297 5297 15:07 Of the all the books this maintains the highest average altitude. The underfoot conditions are generally very good but it is the only book route that includes a reasonable amount of traversing around the back of corries (in the southernmost section), always sloping the same way, of course, leading to sore feet and legs. The linear route is very similar to Steve Birkenshaw’s with just a few links broken and new ones inserted in the southernmost section. The circular route is longer because of the large distance between Clough Head and Great Mell Fell. You could start at the foot of Great Mell Fell and drop into St. John’s in the Vale after Clough Head for another linear route, but I’d prefer to complete the circle. Your route choices when doing the circular route are when to take in Sheffield Pike and by what route you return to the high ridge after visiting Birkhouse Moor. From Gowbarrow Fell you could head south initially before turning to pass Aira Force and dropping diagonally to the A- road where a good path runs alongside. After following this for a kilometre you could head up towards Sheffield Pike or continue a bit further and head for Glenridding Dodd, leaving Sheffield Pike until later. The latter could then be visited after Raise, followed by Hart Side. -

Walking Maps of the Lake District

Walking maps of the Lake District David Stone 29th January 2009 Abstract awkwardness when the edges do not match natural boundaries. Their delineation of footpaths is not This reviews the maps of the Lake District (in the what walkers need: on 1:25 000 maps, rights-of-way north-west of England) which are intended for walk- are given prominence over actual paths; on 1:50 000 ers. The Lake District is rather different from the rest maps, rights-of-way in red are lost against the orange- of the country in what is and has been available. brown contour lines. These are not drastic failings, but they are signifi- Introduction cant. In most parts of the United Kingdom the choice of maps for walking is straightforward: either 1:50 000 Wainwright’s Guides and the or 1:25 000, both published by the Ordnance Survey. O.S. In the Lake District there is more choice: Harvey’s Maps have produced maps which cover most of the In his first guide, published in 1955, Wainwright area at 1:40000 or 1:25000. Wainwright’s Guides wrote [40, Introduction: Notes on the Illustrations]: also include maps at 1:31 680. Thus the choice is much less obvious. the best literature of all for the walker In this note I only cite the maps I have; they in- is that published by the Ordnance Survey, the 1′′ map for companionship and guidance clude examples of almost all types and series pub- 1 ′′ lished in recent decades, and reflect my own choices on expeditions, the 2 2 map for exploration for hillwalking. -

Lake District Hewitts

Lake District Hewitts Climbed Date Name Metres Feet 1 Scafell Pike 978 m 3209 ft 2 Scafell 964 m 3163 ft 3 Helvellyn 950 m 3117 ft 4 Ill Crag 935 m 3068 ft 5 Broad Crag 934 m 3064 ft 6 Skiddaw 931 m 3054 ft 7 Great End 910 m 2986 ft 8 Bowfell 902 m 2959 ft 9 Great Gable 899 m 2949 ft 10 Pillar 892 m 2927 ft 11 Catstye Cam 890 m 2920 ft 12 Esk Pike 885 m 2904 ft 13 Raise 883 m 2897 ft 14 Fairfield 873 m 2864 ft 15 Blencathra 868 m 2848 ft 16 Skiddaw Little Man 865 m 2838 ft 17 White Side 863 m 2831 ft 18 Crinkle Crags 859 m 2818 ft 19 Dollywaggon Pike 858 m 2815 ft 20 Great Dodd 857 m 2812 ft 21 Grasmoor 852 m 2795 ft 22 Stybarrow Dodd 843 m 2766 ft 23 Scoat Fell 841 m 2759 ft 24 St Sunday Crag 841 m 2759 ft 25 Crag Hill 839 m 2753 ft 26 Crinkle Crags South Top 834 m 2736 ft 27 Black Crag 828 m 2717 ft 28 High Street 828 m 2717 ft 29 Red Pike (Wasdale) 826 m 2710 ft 30 Hart Crag 822 m 2697 ft 31 Shelter Crags 815 m 2674 ft 32 Lingmell 807 m 2648 ft 33 High Stile 807 m 2648 ft 34 Old Man of Coniston 803 m 2635 ft 35 Kirk Fell 802 m 2631 ft 36 High Raise 802 m 2631 ft 37 Swirl How 802 m 2631 ft 38 Green Gable 801 m 2628 ft 1 39 Haycock 797 m 2615 ft 40 Green Side 795 m 2608 ft 41 Dove Crag 792 m 2598 ft 42 Rampsgill Head 792 m 2598 ft 43 Grisedale Pike 791 m 2595 ft 44 Kirk Fell East Top 787 m 2582 ft 45 Allen Crags 785 m 2575 ft 46 Thornthwaite Crag 784 m 2572 ft 47 Glaramara 783 m 2569 ft 48 Harter Fell 778 m 2552 ft 49 Dow Crag 778 m 2552 ft 50 Red Screes 776 m 2546 ft 51 Sail 773 m 2536 -

Patterdale Helvellyn, Fairfield and the East

WALKING THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS PATTERDALE HELVELLYN, FAIRFIELD AND THE EAST MARK RICHARDS CICERONE CONTENTS © Mark Richards 2020 Second edition 2020 Map keys ..................................................5 ISBN: 978 1 78631 034 7 Volumes in the series .........................................6 Author preface ..............................................9 Originally published as Lakeland Fellranger, 2008 Starting points ..............................................10 ISBN: 978 1 85284 541 4 INTRODUCTION ..........................................13 Printed in China on responsibly sourced paper on behalf of Valley bases ...............................................13 Latitude Press Ltd Fix the Fells ...............................................15 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Using this guide ............................................15 All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated. Safety and access ...........................................18 All artwork is by the author. Additional online resources ...................................18 FELLS ...................................................19 Maps are reproduced with permission from HARVEY Maps, 1 Arnison Crag ............................................19 www.harveymaps.co.uk 2 Birkhouse Moor .........................................24 3 Birks ..................................................32 4 Catstycam ..............................................37 5 Clough Head............................................42