Déjà Vu and the Timequake: Beyond Postmodernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Evaluations & Competitions

EVALUATIONS & COMPETITIONS EVALUATIONS TEAM DANCE MOCK EVALUATION • Valuable feedback from the Staff prior to final evaluation TEAM DANCE FINAL EVALUATION • Approximately 20 sec. of each style: pom, jazz, and hip hop • Each team will receive written feedback and a rating of Outstanding, Excellent or Superior GAME DAY PRACTICE RUN • Time allotted for teams participating in the Game Day Bid Evaluation to practice on the floor prior to the competition GAME DAY BID EVALUATION • Participation is Optional • Teams learn a Band Chant routine by video link prior to camp along with their own fight song and perform in the Game Day Run Off on Day One • Approximately 1 minute routine COMPETITIONS ALL competitions are completely optional. Note: No crossover participation by individuals is allowed. • Team Dance (Each team within a division will receive a placement; 1st-3rd place receive a trophy) • Game Day Run-Off (All teams compete in division one day 1, Division Winners compete again on Final Day; Winner receives Gold Paid Bid) TOP GUN Each team is allowed up to 2 participants for each Top Gun Competition. This does not have to be the same 2 dancers for each category. Selection of participants for each team is up to the discretion of the Coach. TOP GUN LEAPS & JUMPS • Minimum of five leaps and jumps • Variety of Advanced/Elite leaps and jumps with excellent technique TOP GUN TURNS • Variety of Advanced/Elite turns with excellent technique TOP GUN HIP HOP • Maximum 30 sec. hip hop improvisation • NDA will provide music, dancers will perform in groups DANCE ALL-AMERICAN MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS • Dancers will be nominated by the NDA Staff based on leadership, performance and technical skills • Nominees will perform Team Dance for their audition *Las Vegas Camp will have separate choreography for All-American Audition NATIONALS BIDS SEE REQUIREMENTS AND DISTRIBUTION PROCESS. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

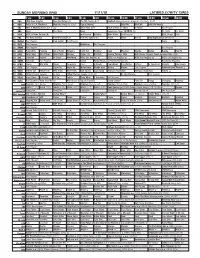

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Download Reading List (PDF)

Delve Deeper into Racing Dreams A Film by Marshall Curry This resource list, compiled by Patrick, Danica, with Laura Farrey, Tom. Game On: The All- Gina Blume of the Monroe Morton. Crossing the Line. New American Race to Make Township Public Library, York: Touchstone, 2007. Champions of Our Children. includes books, films and other This is a collection of inspirational New York: ESPN, 2008. materials related to the issues stories and insights into this Investigative journalist Tom Farrey presented in the film Racing author’s groundbreaking success examines the lives of child athletes Dreams. from go-karting to becoming an and the consequences associated Indy car champion. with extreme competition at an Fondly described as "Talladega early age, including rising obesity Nights meets Catcher in the Rye," Wood, Denise. NASCAR Women: rates, unruly sideline behavior, and Racing Dreams chronicles a year in At the Heart of Racing. Phoenix: reduced activity in children. the life of three tweens who dream David Bull Publishing, 2003. of becoming NASCAR drivers. The Denise Wood, a journalist and Hyman, Mark. Until It Hurts: film by Marshall Curry (Oscar®- public relations representative for America's Obsession with Youth nominated Street Fight, POV 2005; several race teams, reveals the Sports and How It Harms Our Sundance winner If a Tree Falls, integral part women have played Kids. Boston: Beacon Press, POV 2011) is a humorous and both behind the scenes and in the 2010. heartbreaking portrait of racing, public eye of the NASCAR Journalist and Professor Mark young love and family struggle. organization. Hyman investigates the perils of today’s youth sports culture and the ADULT NONFICTION Coming of Age outcome of coaches and parents pushing children beyond their Karting Davis, John A. -

“Larger Than Life” Competition Recognizing Excellence in Cinema

THE ONE CLUB AND NATIONAL CINEMEDIA INTRODUCE NEW LARGER THAN LIFE COMPETITION RECOGNIZING EXCELLENCE IN CINEMA ADVERTISING ~ Winning Entrant Eligible for Prestigious One Show Gold Pencil ~ Winning Cinema Advertising Entry to be Produced by RSA Films NEW YORK (May 10, 2006) - The One Club, the world's foremost non-profit organization for the recognition and promotion of excellence in advertising, and National CineMedia, the leading digital content and advertising provider for movie theatres in the U.S., are partnering to broaden the One Show Non-Broadcast category to include a new cinema advertising competition. The new cinema category invites the creative community to submit storyboards beginning in September 2006 for a 60 second cinema advertisement. The storyboards will be judged by the 2007 One Show jury of award-winning art directors, copywriters and creative directors with the category winner becoming eligible for the prestigious Gold Pencil award, considered the pinnacle of achievement in the advertising field. National CineMedia will award the production resources of RSA Films, as well as media for the finished advertisement to be showcased to over 10 million moviegoers in approximately 425 theatres on 4,200 movie screens throughout the U.S. Award-winning RSA Films is one of the world’s leading commercial advertising and music video production companies. Founded by Sir Ridley Scott (“Bladerunner,” “Alien,” “Gladiator”) and Tony Scott (“Top Gun,” “True Romance,” “Enemy of the State”), the company will produce the winning entrant’s cinema advertising campaign. “The competition is a unique opportunity for The One Club to promote and recognize new creative concepts in cinema advertising. -

Scoreboard: City of Aventura 2020 Winter Adult Softball League

Scoreboard: City of Aventura 2020 Winter Adult Softball League Date Team Opponent Score Game At Game Highlights 1/5/2020 Los Titanes vs Minyan 9-8 Minyan 8:15a Minyan comes from behind to beat Los Titanes in their league debut 1/5/2020 Ely-M vs Aventura's Finest 14-0 Finest 9:30a Finest absolutely hammers Ely-M with stellar defense and some solid hitting 1/5/2020 Team Ramrod vs I Miss Elyse 21-1 Elyse 10:45a I Miss Elyse throttles Team Ramrod in their league debut with a mercy run win after three innings 1/5/2020 Top Gun vs Lightly Toasted 10-9 Toasted 12:00p Toasted wins with a game ending double play that included a play at the plate 1/12/2020 Aventura's Finest vs Team Venezuela 6-4 Finest 8:15a Finest beats Venezuela in a rematch of the 2019 Fall Championship 1/12/2020 Minyan vs Team Ramrod 17-2 Minyan 9:30a Minyan runs away with it behind some strong defence and stellar pitching 1/12/2020 Los Titanes vs Top Gun 15-7 Top Gun 10:45a Top Gun bats come alive as they down Los Titanes 1/12/2020 Lightly Toasted vs Los Titanes 12-4 Toasted 12:00p Toasted continues its winning ways by easily handling Los Titanes 1/19/2020 Team Ramrod vs Lightly Toasted 19-7 Toasted 8:15a Toasted pulls away with hot bats to extend their winning streak to three 1/19/2020 Team Venezuela vs Top Gun 16-2 Venezuela 9:30a Venezuela pounds Top Gun with a steady onslaught of hits 1/19/2020 Minyan vs Ely-M 12-10 Ely-M 10:45a Ely-M holds on in a tight game vs Minyan 1/19/2020 Ely-M vs Los Titanes 17-1 Ely-M 12:00p Ely-M breaks out the bats big time with a thrashing of -

Cannes Critics Week Panel Films Screened During TIFF Cinematheque's Fifty Years of Discovery: Cannes Critics Week (Jan. 18-22

Cannes Critics Week panel Films screened during TIFF Cinematheque’s Fifty Years of Discovery: Cannes Critics Week (Jan. 18-22, 2012) In honour of the fiftieth anniversary of Semaine de la Critique (Cannes Critics Week), TIFF Cinematheque invited eight local and international critics and opinion-makers to each select and introduce a film that was discovered at the festival. The diversity of their selections—everything from revered art-house classics to scrappy American indies, cutting-edge cult hits and intriguingly unknown efforts by famous names—testifies to the festival’s remarkable breadth and eclecticism, and its key role in discovering new generations of filmmaking talent. Programmed by Brad Deane, Manager of Film Programmes. Clerks. Dir. Kevin Smith, 1994, U.S. 92 mins. Production Co.: View Askew Productions / Miramax Films. Introduced by George Stroumboulopoulos, host of CBC’s Stroumboulopoulos Tonight, formerly known as The Hour. Stroumboulopoulos on Clerks: “When Kevin Smith made Clerks and it got on the big screen, you felt like our voice was winning.” Living Together (Vive ensemble). Dir. Anna Karina, 1973, France. 92 mins. Production Co.: Raska Productions / Société Nouvelle de Cinématographie (SNC). Introduced by author and former critic for the Chicago Reader, Jonthan Rosenblum. Rosenblum on Living Together: “I saw Living Together when it was first screened at Cannes in 1973, and will never forget the brutality with which this gently first feature was received. One prominent English critic, the late Alexander Walker, asked Anna Karina after the screening whether she realized that her first film was only being shown because she was once married to a famous film director; she sweetly asked in return whether she should have therefore rejected the Critics Week’s invitation. -

TONY NOBLE Production Designer

The Screen Talent Agency 020 7729 7477 TONY NOBLE Production Designer Tony has production designed high profile campaigns for some of the biggest names in British commercials, including Ridley Scott, Tony Scott, Hugh Hudson, Alan Parker, Patricia Murphy, John Henderson and Paul Weiland. Moving into features, Tony went on to art direct Gavin Hood’s RENDITION and was the UK concept artist for Robert De Niro’s THE GOOD SHEPHERD, but his best-known work is to be seen on the highly acclaimed and multiple award winning MOON. Reel Film Reviews and Screaming Blue Review referred to Tony’s designs as ‘jaw dropping’ and ‘perfect’. Tony is based in London and available for work worldwide. www.tonynoble.co.uk Selected credits date production director / producer / production company television: 2019 MARTIN’S CLOSE Mark Gatiss / Isibeal Balance / Adorable Media – BBC4 2003 BROKEN MORNING Jack Bond / Jack Bond / ITV feature films: 2019 TWIST Martin Owen / Ben Grass / Unstoppable Entertainment 2019 FOR LOVE OR MONEY Mark Murphy / Eric Woollard-White / Solar Productions 2019 THE INTERGALACTIC ADVENTURES OF Martin Owen / Alan Latham / Goldfinch MAX CLOUD 2018 PERIPHERAL Paul Hyett / Bill Kenwright / Bill Kenwright Films 2018 THE COVENANT Paul Hyett / Michael Riley / Sterling Films 2017 SOLIS Carl Strathie / Charlette Kilby / GSP Studios 2016 THE CRUCIFIXION Xavier Gens / Leon Clarance / Motion Picture Capital 2015 AWAITING Mark Murphy / Alan Latham / GSP Studios 2015 TREEHOUSE Michael G. Bartlett / Michael Guy Ellis / Aunt Max Entertainment 2015 THE COMEDIAN'S -

Gorinski2018.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Automatic Movie Analysis and Summarisation Philip John Gorinski I V N E R U S E I T H Y T O H F G E R D I N B U Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Language, Cognition and Computation School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract Automatic movie analysis is the task of employing Machine Learning methods to the field of screenplays, movie scripts, and motion pictures to facilitate or enable vari- ous tasks throughout the entirety of a movie’s life-cycle. From helping with making informed decisions about a new movie script with respect to aspects such as its origi- nality, similarity to other movies, or even commercial viability, all the way to offering consumers new and interesting ways of viewing the final movie, many stages in the life-cycle of a movie stand to benefit from Machine Learning techniques that promise to reduce human effort, time, or both. -

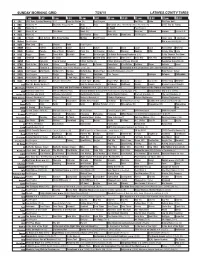

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

Weekend Movie Schedule Pictures Fuel Fantasies

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, February 24, 2006 5 sick. Your concerns about the baby are MONDAY EVENING FEBRUARY 27, 2006 justified, and you have kept this secret too 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 long. Please tell the parents-to-be so they E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Pictures fuel fantasies Flip House House flip. Confronting Evil: America Rollergirls: Searching for Crossing Jordan (TV14) Flip House House flip. can protect their little one from your 36 47 A&E (TVPG) Undercover Ann Calvello (HD) (TVPG) mother. Because you are afraid you may DEAR ABBY: I was visiting my abigail Wife Swap: Schachtner/ The Bachelor: Paris Travis chooses his mate in the KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel not be believed, start out this way: “You 4 6 ABC Martincak (N) season finale. (N) at 10 (N) (TV14) friend, “Carla,” last week and arrived a van buren may have wondered why I don’t get Animal Cops: Down and In Animal Cops - Detroit: Animal Precinct: Too Late Animal Cops: Down and In Animal Cops - Detroit: little early on our way to go shopping. 26 54 ANPL along with Mother. This is the reason — Danger (TVPG) Wounded by Wire (TV G) Danger (TVPG) Wounded by Wire While I was waiting for her to dress, I The West Wing: Internal Kathy Griffin: The D-List Outrageous Outrageous Project Runway: What’s Outrageous Outrageous and I’m worried about the safety of your 63 67 BRAVO noticed some photographs on her kitchen Displacement (HD) Celebrity culture.