10. Chapter 8--Managerialism, Irrationality and Authoritarianism.Wps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

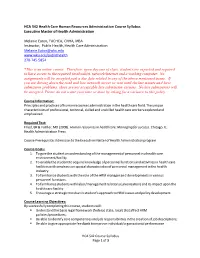

HCA 542 Health Care Human Resources Administration Course Syllabus Executive Master of Health Administration

HCA 542 Health Care Human Resources Administration Course Syllabus Executive Master of Health Administration Melanie Eaton, FACHCA, CNHA, MBA Instructor, Public Health, Health Care Administration [email protected] www.wku.edu/publichealth 270-745-5854 *This is an online course. Therefore, upon day one of class, students are expected and required to have access to the required textbook(s), network/internet and a working computer. No assignments will be accepted past a due date related to any of the above mentioned issues. If you are driving down the road and lose network access or wait until the last minute and have submission problems, these are not acceptable late submission excuses. No late submissions will be accepted. Please do not waste your time or mine by asking for a variance to this policy. Course Information: Principles and practices of human resources administration in the health care field. The unique characteristics of professional, technical, skilled and unskilled health care workers explored and emphasized. Required Text: Fried, BR & Fottler, MD (2008). Human resources in healthcare: Managing for success. Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press. Course Prerequisite: Admission to the Executive Master of Health Administration program. Course Goals: 1. To give the student an understanding of the management of personnel in a health care environment/facility. 2. To enable the student to acquire knowledge of personnel functions and activities in health care facilities with emphasis on special characteristics of personnel management in the health industry. 3. To familiarize students with the role of the HRM manager and developments in various personnel functions. 4. To familiarize students with labor/management relations (unionization) and its impact upon the health care facility. -

Basic Understanding on Supply Chain in Management by Eliot Messiah K

Global Journal of Management and Business Research: A Administration and Management Volume 17 Issue 3 Version 1.0 Year 2017 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4588 & Print ISSN: 0975-5853 Basic Understanding on Supply Chain in Management By Eliot Messiah K. Afli & Dr. Jin Mei Lanzhou Jiaotong University Abstract- There has been some few definitions about what effective management of an organization should be, the structures to put in place so as to get the best administration of the organization. This study looks at the supply chain in the direction of an organization, its importance, and design. This study, however, concluded that it is useful for every business to have a supply chain in the organization since it does coordinate the people and activities within including those outside the organization and that it also maximize profit by eliminating unnecessary cost. Keywords: supply chain system, supply chain design, innovation, management. GJMBR-A Classification: JEL Code: M19 BasicUnderstandingonSupplyChaininManag ement Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2017. Eliot Messiah K. Afli & Dr. Jin Mei. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Basic Understanding on Supply Chain in Management Eliot Messiah K. Afli α & Dr. Jin Mei σ Abstract- There has been some few definitions about what Mary Parker Follett (1868-1933) said: effective management of an organization should be, the "management is to get things done through people." structures to put in place so as to get the best administration She described management to be a philosophy. -

Prison Managerialism in an Age of Austerity

Afterword: ‘It’s a New Way, But ...What Have They Lost?’: Prison Managerialism in an Age of Austerity As the original fieldwork for this book was being completed, the financial crisis of 2007 and 2008 was breaking and in its aftermath came a period of economic recession and fiscal austerity. This has touched upon all aspects of life in a myriad of ways, including prisons. This Afterword is intended to explore the impacts of this age of austerity upon the working lives of prison managers and to consider how this has altered the nature of prison managerialism. It draws upon addi- tional fieldwork conducted in one of the original research sites in 2014 and 2015, including five days of observations and 16 interviews. The Afterword opens by outlining the context both in terms of the national economic plan implemented in the wake of the crisis and in particular follow- ing the election of the Coalition Government in 2010. It also outlines the broad approaches adopted by prisons in order to reduce costs and their impact. The next section explores the empirical material generated from the additional fieldwork. This focuses on two major themes. The first is the shift from performance man- agement to change management, examining how managers have had to guide through a series of significant reforms and the effects that this has had. The sec- ond theme considers the changing nature of prison managers’ working world, particularly how it has come to reflect aspects of what has been described as ‘new capitalism’ (Sennett, 2004). The Afterword then concludes with reflections upon the working lives of prison managers and in particular the nature of prison managerialism. -

Environmental Protection and Natural Resources Roberto Sánchez-Rodríguez, University of California, Riverside Stephen Mumme, Colorado State University

USMEX WP 10-01 Environmental Protection and Natural Resources Roberto Sánchez-Rodríguez, University of California, Riverside Stephen Mumme, Colorado State University Mexico and the United States: Confronting the Twenty-First Century This working paper is part of a project seeking to provide an up-to-date assessment of key issues in the U.S.-Mexican relationship, identify points of convergence and diver- gence in respective national interests, and analyze likely consequences of potential policy approaches. The project is co-sponsored by the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies (San Diego), the Mexico Institute of the Woodrow Wilson Center (Washington DC), El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Tijuana), and El Colegio de México (Mexico City). Environmental Protection and Natural Resources Roberto Sanchez-Rodriguez and Steven Mumme The current era of global environmental problems is forcing societies to redefine their relationship with nature. The debate of climate change has raised the attention and importance of the environment at international, national, and sub-national levels. The environment has been addressed as an afterthought of economic, physical, and demographic growth. Environmental problems are still considered a technical problem in order to avoid addressing, as much as possible, the socioeconomic and political driving forces creating them and their consequences for societies and nature. The current operational model for the environment followed in many countries, including the U.S. and Mexico, favors fragmented perspectives of complex problems. We place the discussion of environmental issues between Mexico and the United States within this context. Environmental issues and the management of natural resources have become a significant element of the binational relationship between Mexico and the United States during the last three decades. -

Telehealth Governance Page 1 of 20 Telehealth Governance: an Essential Tool to Empower Today’S Healthcare Leaders

1743. Arkwright. Telehealth Governance https://doi.org/10.30953/tmt.v2.12 Page 1 of 20 Telehealth Governance: An Essential Tool to Empower Today’s Healthcare Leaders Bryan Arkwright, Jeff Jones, Thomas Osborne, Guy Glorioso, John Russo, Jr. Strong telehealth governance serves as the cornerstone for advancing a telehealth strategy by ensuring that the health system has the intentional leadership infrastructure to compete and excel in this fast-paced and transforming industry.1 A Conceptual Framework Effective governance is the essential first step towards successful management. The former informs the latter to optimize value to the stakeholders. Paraphrasing the Financial Reporting Council, corporate (telehealth) governance should contribute to better company performance by helping a board discharge its duties in the best interests of stakeholders: executive leadership, management, staff, customers, patients, vendors, communities, and regulators, etc. Good governance facilitates efficient, effective, and entrepreneurial management that can deliver value over the longer term. If ignored, the consequences may be vulnerability or poor performance (Financial Reporting Council, 2008). The authors embrace a philosophical argument for governance, that emphasizes active risk management and resource management to ensure alignment between long- and short-term strategies. This is accomplished through leadership, accountability, and responsibility in accord with the organization’s mission, vision, and values. Three key functions of telehealth governance are explored here: management, prioritization of services, and achieving return on investment (ROI). In addition, how long it takes to create governance and milestones that define progress over time are addressed. Telehealth Management Capability Telehealth management capability provides the organization with timely, thorough, relevant, and accurate information about the telehealth industry. -

Strategic Human Resource Management

2nd Edition STRATEGIC HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT An INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE Edited by Gary Rees & Paul E. Smith 00_Rees_Smith_Prelims.indd 3 4/22/2017 5:17:07 PM SAGE Publications Ltd Gary Rees and Paul E. Smith 2017 1 Oliver’s Yard 55 City Road First edition published 2014, reprinted 2014, 2016. London EC1Y 1SP This second edition published 2017 SAGE Publications Inc. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or 2455 Teller Road private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Thousand Oaks, California 91320 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the B 1/I 1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in Mathura Road accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright New Delhi 110 044 Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. SAGE Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd 3 Church Street All material on the accompanying website can be printed #10-04 Samsung Hub off and photocopied by the purchaser/user of the book. The Singapore 049483 web material itself may not be reproduced in its entirety for use by others without prior written permission from SAGE. The web material may not be distributed or sold separately from the book without the prior written permission of SAGE. Should anyone wish to use the materials from the website for conference purposes, they would require separate permission Editor: Kirsty Smy from us. -

Employee Management Techniques Transient Fads Or Trending Fashions

Employee-management In this theory development case study, we focus on the Techniques: Transient relations across recurrent waves in the amount and kind of language promoting and diffusing, and then demoting Fads or Trending and rejecting, management techniques—techniques for Fashions? transforming the input of organizational labor into organi- zational outputs. We suggest that rather than manifesting Eric Abrahamson themselves as independent, transitory, and un-cumulative Columbia University fads, the language of repeated waves cumulates into Micki Eisenman what we call management fashion trends. These trends are protracted and major transformations in what man- Baruch College agers read, think, express, and enact that result from the accumulation of the language of these consecutive waves. For the language of five waves in employee-man- agement techniques—management by objectives, job enrichment, quality circles, total quality management, and business process reengineering—we measure ratio- nal and normative language suggesting, respectively, that managers can induce labor financially or psychologically. The results reveal a gradual intensification in the ratio of rational to normative language over repeated waves, sug- gesting the existence of a management fashion trend across these techniques. Lexical shifts over time, howev- er, serve to differentiate a fashion from its predecessor, creating a sense of novelty and progress from the earlier to the later fashions. Scholars have recognized for a long time now that so-called fads or fashions affect management techniques (Sumner, 1959), those linguistic prescriptions for how to transform organizational inputs into organizational outputs (Ghaziani and Ventresca, 2005). The “balanced score card” label, for exam- ple, denotes language prescribing behaviors necessary to transform certain financial and non-financial results into multi- dimensional measures of organizational performance. -

A New Model for a District Health System Supply Chain: Proposition and Application from Classic to Coronavirus Care

▪ RAHIS, Revista de Administração Hospitalar e Inovação em Saúde Vol. 17, n1 ▪ Belo Horizonte, MG ▪ JAN/MAR 2020 ▪e-ISSN: 2177- 2754 e ISSN impresso: 1983-5205 ▪ DOI: https://doi.org/10.21450/rahis.v17i1.6180 ▪ Submetido: (30/04/2020) ▪ Aceito: (20/05/2020) ▪ Sistema de avaliação: Double Blind Review ▪p. 21 - 33. A NEW MODEL FOR A DISTRICT HEALTH SYSTEM SUPPLY CHAIN: PROPOSITION AND APPLICATION FROM CLASSIC TO CORONAVIRUS CARE UM NOVO MODELO PARA UMA CADEIA DE SUPRIMENTOS DO SISTEMA DE SAÚDE DISTRITAL: PROPOSIÇÃO E APLICAÇÃO DO ATENDIMENTO CLÁSSICO AO CORONAVIRUS UN NUEVO MODELO PARA UNA CADENA DE SUMINISTRO DEL SISTEMA DE SALUD DISTRITAL: PROPOSICIÓN Y APLICACIÓN DE LA ATENCIÓN CLÁSICA AL CORONAVIRUS José Edson Lara Centro Universitário Unihorizontes e Fundação Pedro Leopoldo [email protected] Bruno Pelizzaro Afonso Instituto Federal de Minas Gerais [email protected] Paulo Emílio Instituto de Educação Tecnológica [email protected] Tarcísio Afonso Fundação Pedro Leopoldo [email protected] Este é um artigo de acesso aberto distribuído sob os termos da Creative Commons Attribution License This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License Este es un artículo de acceso abierto distribuido bajo los términos de la Creative Commons Attribution License REVISTA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO E INOVAÇÃO HOSPITALAR Revista de Administração Hospitalar e Inovação em Saúde Vol. 17, n.1 ▪ Belo Horizonte, MG ▪ JAN/MAR 2020 ABSTRACT Rationale: The theme of health today has been the most worrying in the world and in Brazil. Its context and management have generated academic, political and administrative discussions around the world. -

The Customer Differential

Concentrated Knowledge™ for the Busy Executive • www.summary.com Vol. 23, No. 11 (3 parts) Part 3, November 2001 • Order # 23-28 FILE: MANAGEMENT STRATEGIC ® The Complete Guide to Implementing CRM THE CUSTOMER DIFFERENTIAL THE SUMMARY IN BRIEF One company took 12 months and 12 employees to institute a data warehousing project as part of a corporate-wide customer relationship man- agement (CRM) effort, without any appreciable results. Another company By Melinda Nykamp was stymied by the incredible complexities of the processes needed in its CRM effort and had to put the effort on hold almost a year before the right data collection and storage systems were in place. Any company that has CONTENTS begun to implement a CRM plan knows it can be a time-consuming task Defining Customer involving a multitude of business processes and infrastructure dependen- Relationship Management cies; much broader organizational change than initially thought; and exten- Pages 2, 3 sive learning of customer-centric and data-driven marketing concepts. CRM: An Integrated Nevertheless, although it might be easy to dismiss CRM as just another Approach management fad, there are some compelling reasons to take another look at Page 3 this trend. CRM Requires Complete First, customers — aided by the technology of the Internet, in particular Transformation — have much more power and influence than ever before. Customers today Of the Company Pages 3, 4 have higher expectations on service, price and delivery. Second, advances in computer systems are giving companies the ability The Case for CRM to collect and analyze specific, up-to-the-minute customer data. -

HSPM 7336 - the Healthcare Supply Chain

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Public Health Syllabi Public Health, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Fall 2016 HSPM 7336 - The Healthcare Supply Chain David E. Schott Georgia Southern University, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/coph-syllabi Part of the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Schott, David E., "HSPM 7336 - The Healthcare Supply Chain" (2016). Public Health Syllabi. 94. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/coph-syllabi/94 This other is brought to you for free and open access by the Public Health, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Health Syllabi by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Georgia Southern University Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health HSPM 7336: The Healthcare Supply Chain Fall 2016 Instructor: David E Schott, DrPH, MBA, CPH Office: Hendricks Hall Room 2009A Phone: (229) 474-9199 E-Mail Address: [email protected] email is preferred communication method Office Hours: Tuesday: after class; other times by appointment. Web Page: Folio Class Meets: Tuesdays: 6:30 pm - 9:15 pm; Information Technology Building Room 2203. -- Course schedules can be found at: http://www.collegesource.org/displayinfo/catalink.asp -- Prerequisites: Admission to the MHA Program Web-CT Address: The URL will be available one week prior to the course start date. Catalog Description: The healthcare supply chain is a vital core business component of the health organization with the mission of delivering the technological elements of the patient care process to the providers of care. -

Learning Organization: a Fine Example of a Management Fad | BEH

Learning organization: a fine example of a management fad | BEH: www.beh.pradec.eu Peer-reviewed and Open access journal BEH - Business and Economic Horizons ISSN: 1804-5006 | www.academicpublishingplatforms.com Volume 14 | Issue 3 | 2018 |pp.477-487 The primary version of the journal is the on-line version DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15208/beh.2018.34 Learning organization: A fine example of a management fad Slobodan Adžić Arab Open University, Kuwait corresponding e-mail: sadzic[at]aou(dot)edu{d}.kw address: Arab Open University, 6 St, Al-Ardiya, Kuwait Abstract: The management theories of no practical value are known as management fads. One of those management fads - which is the focus of this research - is learning organization. There is sufficient evidence in English literature to conclude that learning organization is a management fad. The aim of this paper is to present the ample evidence that learning organization is a management fad. The maximum number of the research paper with the subject of learning organization was made in the late 1995 and the typical bell- shaped curve of the management fad is evident. In contrast to the world trend, a content analysis of Serbian journals discovered that a typical pick of a bell-shaped curve of papers covering the topic of learning organi- zation was 17 years later. It is argued in this paper that the learning organization phenomenon, as a norma- tive or prescriptive theory, should be abandoned in the academic world altogether. The learning organization fad is a phenomenon with low practical applicability, a phenomenon of a little value for further development in the management research. -

Managerialism and the Demise of the Big Three

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Managerialism and the Demise of the Big Three Locke, Robert University of Hawaii at Manoa November 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/18996/ MPRA Paper No. 18996, posted 04 Dec 2009 23:22 UTC 1 Managerialism and the Demise of the Big Three By Robert R Locke Abstract: This essay is about the crisis of US automobile management and the difficulties that management educators and practitioners in America have had facing up to that crisis. It focuses on Detroit’s Big Three but it also looks at the role Japanese firms played in transferring JMS (Japanese Management Systems) to America, particularly the transfer of TPS (the Toyota Production System) to Georgetown, Kentucky. It opens (I) with a discussion of the triumph of a science-based “New Paradigm” in business school management education and in industry, with reference to its critics, in order to establish the institutional framework within which US automobile management expanded and operated after World War II; then (II) a more general discussion ensues in which U.S. managerialism and JMS are compared, and the pathways and barriers to the transfer of JMS to America both to US firms and to Japanese transplants are explored, before in the last part (III) the focus narrows to a specific case of transfer: H. Thomas Johnson’s analysis of Toyota’s successful alternative Production System (TPS) at Georgetown and how it supersedes in theory and practice the managerial methods of the Big Three. Managerialism -- What occurs when a special group, called management, ensconces itself systemically in organizations and deprives owners and employees of decision-making power (including the distribution of emoluments) – and justifies the takeover on the grounds of the group’s education and exclusive possession of the codified bodies of knowledge and know-how necessary to the efficient running of organizations.