A Health Administration Instructional Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

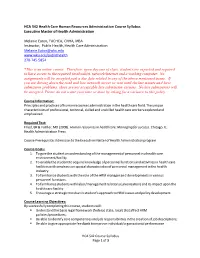

HCA 542 Health Care Human Resources Administration Course Syllabus Executive Master of Health Administration

HCA 542 Health Care Human Resources Administration Course Syllabus Executive Master of Health Administration Melanie Eaton, FACHCA, CNHA, MBA Instructor, Public Health, Health Care Administration [email protected] www.wku.edu/publichealth 270-745-5854 *This is an online course. Therefore, upon day one of class, students are expected and required to have access to the required textbook(s), network/internet and a working computer. No assignments will be accepted past a due date related to any of the above mentioned issues. If you are driving down the road and lose network access or wait until the last minute and have submission problems, these are not acceptable late submission excuses. No late submissions will be accepted. Please do not waste your time or mine by asking for a variance to this policy. Course Information: Principles and practices of human resources administration in the health care field. The unique characteristics of professional, technical, skilled and unskilled health care workers explored and emphasized. Required Text: Fried, BR & Fottler, MD (2008). Human resources in healthcare: Managing for success. Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press. Course Prerequisite: Admission to the Executive Master of Health Administration program. Course Goals: 1. To give the student an understanding of the management of personnel in a health care environment/facility. 2. To enable the student to acquire knowledge of personnel functions and activities in health care facilities with emphasis on special characteristics of personnel management in the health industry. 3. To familiarize students with the role of the HRM manager and developments in various personnel functions. 4. To familiarize students with labor/management relations (unionization) and its impact upon the health care facility. -

Telehealth Governance Page 1 of 20 Telehealth Governance: an Essential Tool to Empower Today’S Healthcare Leaders

1743. Arkwright. Telehealth Governance https://doi.org/10.30953/tmt.v2.12 Page 1 of 20 Telehealth Governance: An Essential Tool to Empower Today’s Healthcare Leaders Bryan Arkwright, Jeff Jones, Thomas Osborne, Guy Glorioso, John Russo, Jr. Strong telehealth governance serves as the cornerstone for advancing a telehealth strategy by ensuring that the health system has the intentional leadership infrastructure to compete and excel in this fast-paced and transforming industry.1 A Conceptual Framework Effective governance is the essential first step towards successful management. The former informs the latter to optimize value to the stakeholders. Paraphrasing the Financial Reporting Council, corporate (telehealth) governance should contribute to better company performance by helping a board discharge its duties in the best interests of stakeholders: executive leadership, management, staff, customers, patients, vendors, communities, and regulators, etc. Good governance facilitates efficient, effective, and entrepreneurial management that can deliver value over the longer term. If ignored, the consequences may be vulnerability or poor performance (Financial Reporting Council, 2008). The authors embrace a philosophical argument for governance, that emphasizes active risk management and resource management to ensure alignment between long- and short-term strategies. This is accomplished through leadership, accountability, and responsibility in accord with the organization’s mission, vision, and values. Three key functions of telehealth governance are explored here: management, prioritization of services, and achieving return on investment (ROI). In addition, how long it takes to create governance and milestones that define progress over time are addressed. Telehealth Management Capability Telehealth management capability provides the organization with timely, thorough, relevant, and accurate information about the telehealth industry. -

A New Model for a District Health System Supply Chain: Proposition and Application from Classic to Coronavirus Care

▪ RAHIS, Revista de Administração Hospitalar e Inovação em Saúde Vol. 17, n1 ▪ Belo Horizonte, MG ▪ JAN/MAR 2020 ▪e-ISSN: 2177- 2754 e ISSN impresso: 1983-5205 ▪ DOI: https://doi.org/10.21450/rahis.v17i1.6180 ▪ Submetido: (30/04/2020) ▪ Aceito: (20/05/2020) ▪ Sistema de avaliação: Double Blind Review ▪p. 21 - 33. A NEW MODEL FOR A DISTRICT HEALTH SYSTEM SUPPLY CHAIN: PROPOSITION AND APPLICATION FROM CLASSIC TO CORONAVIRUS CARE UM NOVO MODELO PARA UMA CADEIA DE SUPRIMENTOS DO SISTEMA DE SAÚDE DISTRITAL: PROPOSIÇÃO E APLICAÇÃO DO ATENDIMENTO CLÁSSICO AO CORONAVIRUS UN NUEVO MODELO PARA UNA CADENA DE SUMINISTRO DEL SISTEMA DE SALUD DISTRITAL: PROPOSICIÓN Y APLICACIÓN DE LA ATENCIÓN CLÁSICA AL CORONAVIRUS José Edson Lara Centro Universitário Unihorizontes e Fundação Pedro Leopoldo [email protected] Bruno Pelizzaro Afonso Instituto Federal de Minas Gerais [email protected] Paulo Emílio Instituto de Educação Tecnológica [email protected] Tarcísio Afonso Fundação Pedro Leopoldo [email protected] Este é um artigo de acesso aberto distribuído sob os termos da Creative Commons Attribution License This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License Este es un artículo de acceso abierto distribuido bajo los términos de la Creative Commons Attribution License REVISTA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO E INOVAÇÃO HOSPITALAR Revista de Administração Hospitalar e Inovação em Saúde Vol. 17, n.1 ▪ Belo Horizonte, MG ▪ JAN/MAR 2020 ABSTRACT Rationale: The theme of health today has been the most worrying in the world and in Brazil. Its context and management have generated academic, political and administrative discussions around the world. -

HSPM 7336 - the Healthcare Supply Chain

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Public Health Syllabi Public Health, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Fall 2016 HSPM 7336 - The Healthcare Supply Chain David E. Schott Georgia Southern University, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/coph-syllabi Part of the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Schott, David E., "HSPM 7336 - The Healthcare Supply Chain" (2016). Public Health Syllabi. 94. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/coph-syllabi/94 This other is brought to you for free and open access by the Public Health, Jiann-Ping Hsu College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Health Syllabi by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Georgia Southern University Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health HSPM 7336: The Healthcare Supply Chain Fall 2016 Instructor: David E Schott, DrPH, MBA, CPH Office: Hendricks Hall Room 2009A Phone: (229) 474-9199 E-Mail Address: [email protected] email is preferred communication method Office Hours: Tuesday: after class; other times by appointment. Web Page: Folio Class Meets: Tuesdays: 6:30 pm - 9:15 pm; Information Technology Building Room 2203. -- Course schedules can be found at: http://www.collegesource.org/displayinfo/catalink.asp -- Prerequisites: Admission to the MHA Program Web-CT Address: The URL will be available one week prior to the course start date. Catalog Description: The healthcare supply chain is a vital core business component of the health organization with the mission of delivering the technological elements of the patient care process to the providers of care. -

Health Administration in Organizing

Sys Rev Pharm 2020;11(12):1214-1217 A multHifaceetedarevlietwhjournAal indthme fieldionf phiasrmtacry ation in Organizing Indonesian Hajj from the Legal and Managerial Perspective of Good Corporate Governance: A Systematic Study Muchammad Shidqon Prabowo 1, Dewi Sulistianingsih2 1Faculty of Law, Wahid Hasyim University, Semarang, Indonesia 2Faculty of Law, Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia ABSTRACT Keywords: This study seeks to analyze health administration in the hajj pilgrimage in Health Administration, Hajj Pilgrimage, Good Corporate Indonesia. Taking a quite different landscape, this study combines health CGovrerrensapncoen, Ldeegnacl Seystem, Quality Management administration in the context of the interests and obligations of the state to Muchammad Shidqon Prabowo provide protection and safety for pilgrims. This protection is related to : aspects of regulations and laws as the basic norms for policymaking at the operational level in the administration of Hajj, especially in the context of Faculty of Law Wahid Hasyim University, Semarang, Indonesia the health of the pilgrims. Meanwhile, the safety aspect is related to the Email:[email protected] fulfillment of managerial aspects to improve service functions and improve quality. By taking an interlinked dialogue from various theoretical outlooks, this study provides a perspective on the relationship between legal and management aspects through good corporate governance and total quality management in the administration of hajj and its basis for pilgrimage health administration. INTRODUCTION Deductively, freedom of religion and worship according The legal principles that develop globally directly and to one's religion as part of human life is protected by indirectly affect the basic principles of national law in the human rights. As an inherent derivation of this obligation country concerned, for example in the economic sector, is in the hajj management. -

Master of Health Administration (MHA) and Leadership (MSL)

Joint Graduate Degree Program Master of Health Administration (MHA) and Leadership (MSL) Gain the leadership and interpersonal skills to direct and develop human resources, including conflict resolution, group dynamics and diversity management through Pfeiffer’s joint degree master of health administration and master of science in leadership (MHA/ MSL) program. The dual degree program is carefully designed to encompass all sectors of healthcare, including hospitals, ambulatory care, mental health, public health, practice management, government policy, long term care, managed care and insurance. Through a combination of lecture, small group study and case study review, classes help you identify and solve managerial problems in real business contexts. Program highlights include international study opportunities in Europe or Canada. Faculty with Real-World APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS Experience • A baccalaureate degree from an accredited college or university • Completed Pfeiffer University admissions application. FLEXIBLE • Official transcripts from all previous colleges or universities attended classroom • Three letters of recommendation from either employers or academia scheduling & online • Satisfactory completion of the Miller Analogies Test (MAT), Graduate Management Admissions Test (GMAT), Graduate Record Examination (GRE) or other standardized graduate admissions test. (Waived for applicants with an undergraduate GPA of at least 2.8/4.0 and at least 5-7 years of relevant work experiences as documented with a professional resume, and/or -

Health Administration and Policy: Dual Degree – JD-MHA

Health Administration and Policy: Dual Degree – JD-MHA The dual degree in law and health administration combines the 3-year Juris Doctorate at the College of Law and the 2-year Masters of Health Administration at the College of Public Health into 4 years of study. The JD requires a minimum of 90 credit hours, and the MHA requires a minimum of 60 credit hours. A dual-degree student will complete 81 credit hours at the College of Law and receive 9 credit hours towards the law degree from coursework completed at the College of Public Health. Likewise, the student will complete 51 credit hours at the College of Public Health and receive 9 credit hours towards the masters degree from coursework completed at the College of Law. How to apply? Students interested in the dual program must be accepted by both colleges. Both degrees will be awarded during the same academic season. A student may begin at either college or apply to both colleges simultaneously. What jobs can I get? This program is designed to prepare the student who plans either to practice law in the healthcare arena or to enter healthcare service organization administration. The relationships between healthcare service organization administration, practice, and policy and law is increasingly interconnected, and it is not unusual to find individuals with legal training and experience in top administrative and policy positions in a variety of healthcare service organizations and governmental settings. Given the growing number of healthcare administration problems in need of solutions, the demand for lawyers, especially at the policy level, with solid administrative training is critical. -

Collaborative Allied Health and Nursing Interprofessional Health Education: Beginning the Journey

Online Journal of Interprofessional Health Promotion Volume 1 Issue 1 Inaugural Issue for the Online Journal of Article 3 Interprofessional Health Promotion October 2019 Collaborative Allied Health and Nursing Interprofessional Health Education: Beginning the Journey Anita Hazelwood University Louisiana Lafayette, [email protected] Lisa Delhomme University of Louisiana Lafayette, [email protected] Scott Sittig University of South Alabama, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.ulm.edu/ojihp Part of the Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hazelwood, A., Delhomme, L., & Sittig, S. (2019). Collaborative Allied Health and Nursing Interprofessional Health Education: Beginning the Journey. Online Journal of Interprofessional Health Promotion, 1(1). Retrieved from https://repository.ulm.edu/ojihp/vol1/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ULM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Journal of Interprofessional Health Promotion by an authorized editor of ULM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hazelwood et al.: Collaborative Health Education Collaborative Allied Health and Nursing Interprofessional Health Education: Beginning the Journey Anita Hazelwood, EdD, RHIA, FAHIMA Professor and Department Head Allied Health Department University of Louisiana at Lafayette Lafayette, Louisiana Lisa Delhomme, MHA, RHIA Program Director and Master Instructor Health Information Management Allied Health Department University of Louisiana at Lafayette Lafayette, Louisiana Scott Sittig, PhD, MHI, RHIA Assistant Professor, Health Informatics School of Computing University of South Alabama Mobile, Alabama Published by ULM Digital Repository, 2019 1 Online Journal of Interprofessional Health Promotion, Vol. -

Can Organisational Culture of Teams Be a Lever for Integrating Care? an Exploratory Study

Tietschert, MV, et al. Can Organisational Culture of Teams Be a Lever for Integrating Care? An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Integrated Care, 2019; 19(4): 10, 1–10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.4681 RESEARCH AND THEORY Can Organisational Culture of Teams Be a Lever for Integrating Care? An Exploratory Study Maike V. Tietschert*, Federica Angeli†, Arno J.A. van Raak‡, Jonathan Clark§, Sara J. Singer‖ and Dirk Ruwaard‡ Introduction: Organisational culture is believed to be an important facilitator for better integrated care, yet how organisational culture impacts integrated care remains underspecified. In an exploratory study, we assessed the relationship between organisational culture in primary care centres as perceived by primary care teams and patient-perceived levels of integrated care. Theory and methods: We analysed a sample of 2,911 patient responses and 17 healthcare teams in four primary care centres. We used three-level ordered logistic regression models to account for the nesting of patients within health care teams within primary care centres. Results: Our results suggest a non-linear relationship between organisational culture at the team level and integrated care. A combination of different culture types—including moderate levels of production- oriented, hierarchical and team-oriented cultures and low or high levels of adhocracy cultures—related to higher patient-perceived levels of integrated care. Conclusions and discussion: Organisational culture at the level of healthcare teams has significant asso- ciations with patient-perceived integrated care. Our results may be valuable for primary care organisations in their efforts to compose healthcare teams that are predisposed to providing better integrated care. -

Supply Chain Management and Its Effect on Health Care Service Quality: Quantitative Evidence from Jordanian Private Hospitals

www.sciedu.ca/jms Journal of Management and Strategy Vol. 4, No. 2; 2013 Supply Chain Management and Its Effect on Health Care Service Quality: Quantitative Evidence from Jordanian Private Hospitals Raeeda Jamal Al-Saa'da1, Yara Khalid Abu Taleb2, Mais Elian Al Abdallat3, Rasmi Abd Alraheem Al-Mahasneh2, Nabil Awni Nimer4 & Ghazi A. Al-Weshah5 1 Princess Iman Research & Lab Science Center-Supply Department-Royal Medical Services, Jordan 2 Central Procurement branch-Royal Medical Services, Jordan 3 Main Medical Stores-Royal Medical Services, Jordan 4 Department of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering, Philadelphia University, Jordan 5 Faculty of Planning & Management, Al-Balqa Applied University, Jordan Correspondence: Dr. Ghazi A. Al-Weshah, Faculty of Planning & Management, Al-Balqa Applied University, Jordan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 5, 2013 Accepted: April 2, 2013 Online Published: April 27, 2013 doi:10.5430/jms.v4n2p42 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/jms.v4n2p42 Abstract The study aims to explore and measure the effect of supply chain management's dimensions (relationship with suppliers, compatibility, specifications and standards, delivery and after-sales service) on the quality of health services' dimensions (responsiveness, trust, and security) in private hospitals in Jordan from the perspective of procurement officers. The study also aims to clarify the differences between supply chain management and quality of health services due to some demographic variables such as (gender, age, education level, and years of experience in the field of supply). The study employs a quantitative design using a hypothesis testing approach to identify the effect of supply chain management dimensions on quality of health services. -

Competencies to What End? Affirming the Purpose of Healthcare Management

Competencies to what end? An oath for healthcare management 133 Competencies to What End? Affirming the Purpose of Healthcare Management James W. Begun, PhD, Peter W. Butler, MHSA, and Mary E. Stefl, PhD Abstract The 2001 National Summit on the Future of Education and Practice in Health Management and Policy in Orlando, Fla., was a significant event in the continu- ing evolution of the profession of healthcare management. The 2001 National Summit signaled a crisis of sorts, with widespread calls for transformation in the education of healthcare managers in the United States. Recommenda- tions from the Summit focused on bridging the academic -practitioner divide, strengthening the applicant pool, and affirming the distinctive nature of healthcare management. The primary lasting consequence of the Summit has been the movement to link the educational curricula of healthcare management programs to competency frameworks. In the meantime, however, healthcare management holds an increasingly tenuous position as a profession. In the rush to address concerns of employer stakeholders, the educational community has neglected attention to more foundational questions about the purpose, values, and role of the healthcare manager. Educators can assume a more proactive leadership stance in distinguishing healthcare management from generic management and in defining a profes- sion that inspires “the best of the best” to enter the field. As a foundational step, we propose explicit adoption of an Oath for Healthcare Management for those entering healthcare management. Please address correspondence to: James W. Begun, PhD, Division of Health Policy and Man- agement, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, D262 Mayo Building, MMC 510, 420 Delaware Street SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455; Phone: (612) 624-9319 Email: [email protected] Acknowledgement: We are grateful to Andrew N. -

An Experience-Based Knowledge Management Approach to Healthcare Quality Improvement

Defense | Homeland Security | Federal | Commercial | Health An Experience-Based Knowledge Management Approach to Healthcare Quality Improvement By: Matthew H. Loxton | Senior Analyst Email: [email protected] | Phone: 703.448.6081 ext. 189 | twitter: @mloxton “Simply put, health care quality is getting the right care to the right patient at the right time – every time” (Dr. Carolyn Clancy, 2009) ©Copyright 2014 Whitney, Bradley, & Brown Inc. Learning from Organizational Experiences Knowledge Management (KM) has many practical applications and operational facets that derive from a common and reusable set of basic principles. The specific application of KM differs from one industry to another, depending on the operational problems being addressed, the nature of the stakeholders, and the environment in which the methods are used. One effective application of KM in healthcare is the use of a lessons learned process to capture essential elements of clinician and other stakeholder experiences, formulate lessons that are reusable, and assist in replicating effective practices and avoiding known pitfalls. Effectively implemented lessons learned processes support organizational learning and increase efficiency and effectiveness of clinical operations by reducing repetition of operational mistakes, increasing organizational diffusion of effective practices and innovations, and increasing standardization. (1) Effective lessons learned processes are: ■ Built into project templates as a required and continuous activity ■ Supported by leadership and the organizational culture ■ Based on an evidence-based, blameless, and systematic process In this whitepaper, we look closer at a particular aspect of the KM lessons learned process and examine how the process is rooted in stakeholder experience, especially those of the front-line clinicians involved.