The Healing Power of the Icaros

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

Chanting in Amazonian Vegetalismo

________________________________________________________________www.neip.info Amazonian Vegetalismo: A study of the healing power of chants in Tarapoto, Peru. François DEMANGE Student Number: 0019893 M.A in Social Sciences by Independent Studies University of East London, 2000-2002. “The plant comes and talks to you, it teaches you to sing” Don Solón T. Master vegetalista 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter one : Research Setting …………………………….…………….………………. 3 Chapter two : Shamanic chanting in the anthropological literature…..……17 Chapter three : Learning to communicate ………………………………………………. 38 Chapter four : Chanting ……………………………………..…………………………………. 58 Chapter five : Awakening ………………………………………………………….………… 77 Bibliography ........................................................................................... 89 Appendix 1 : List of Key Questions Appendix 2 : Diary 3 Chapter one : Research Setting 1. Panorama: This is a study of chanting as performed by a new type of healing shamans born from the mixing of Amazonian and Western practices in Peru. These new healers originate from various extractions, indigenous Amazonians, mestizos of mixed race, and foreigners, principally Europeans and North-Americans. They are known as vegetalistas and their practice is called vegetalismo due to the place they attribute to plants - or vegetal - in the working of human consciousness and healing rituals. The research for this study was conducted in the Tarapoto region, in the Peruvian highland tropical forest. It is based both on first hand information collected during a year of fieldwork and on my personal experience as a patient and as a trainee practitioner in vegetalismo during the last six years. The key idea to be discussed in this study revolves around the vegetalista understanding that the taking of plants generates a process of learning to communicate with spirits and to awaken one’s consciousness to a broader reality - both within the self and towards the outer world. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents General Information........................................................................................................................ 2 Resort Map...................................................................................................................................... 3 Resort Internet Options................................................................................................................... 4 Resort Business Center and Paper Copies ...................................................................................... 4 Resort Restaurants and Bars ......................................................................................................... 11 Schedule of Events........................................................................................................................ 12 Special Events............................................................................................................................... 15 Conference Center Floor Plan....................................................................................................... 18 Technical Program........................................................................................................................ 19 Technical Sessions Monday Session 1: Attitude Dynamics & Control I .................................................................................. 19 Session 2: Attitude Estimation.................................................................................................... -

University Micr6films International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the fllm is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Inner Visions: Sacred Plants, Art and Spirituality

AM 9:31 2 12/10/14 2 224926_Covers_DEC10.indd INNER VISIONS: SACRED PLANTS, ART AND SPIRITUALITY Brauer Museum of Art • Valparaiso University Vision 12: Three Types of Sorcerers Gouache on paper, 12 x 16 inches. 1989 Pablo Amaringo 224926_Covers_DEC10.indd 3 12/10/14 9:31 AM 3 224926_Text_Dec12.indd 3 12/12/14 11:42 AM Inner Visions: Sacred Plants, Art and Spirituality • An Exhibition of Art Presented by the Brauer Museum • Curated by Luis Eduardo Luna 4 224926_Text.indd 4 12/9/14 10:00 PM Contents 6 From the Director Gregg Hertzlieb 9 Introduction Robert Sirko 13 Inner Visions: Sacred Plants, Art and Spirituality Luis Eduardo Luna 29 Encountering Other Worlds, Amazonian and Biblical Richard E. DeMaris 35 The Artist and the Shaman: Seen and Unseen Worlds Robert Sirko 73 Exhibition Listing 5 224926_Text.indd 5 12/9/14 10:00 PM From the Director In this Brauer Museum of Art exhibition and accompanying other than earthly existence. Additionally, while some objects publication, expertly curated by the noted scholar Luis Eduardo may be culture specific in their references and nature, they are Luna, we explore the complex and enigmatic topic of the also broadly influential on many levels to, say, contemporary ritual use of sacred plants to achieve visionary states of mind. American and European subcultures, as well as to contemporary Working as a team, Luna, Valparaiso University Associate artistic practices in general. Professor of Art Robert Sirko, Valparaiso University Professor We at the Brauer Museum of Art wish to thank the Richard E. DeMaris and the Brauer Museum staff present following individuals and agencies for making this exhibition our efforts of examining visual products arising from the possible: the Brauer Museum of Art’s Brauer Endowment, ingestion of these sacred plants and brews such as ayahuasca. -

Projekt Podpořený Operačním Programem Přeshraniční Spolupráce Slovenská Republika – Česká Republika 2007-2013 MEZINÁRODNÍ VESMÍRNÁ STANICE 2010-2011

Projekt podpořený Operačním programem Přeshraniční spolupráce Slovenská republika – Česká republika 2007-2013 MEZINÁRODNÍ VESMÍRNÁ STANICE 2010-2011 Mgr. Antonín Vítek, CSc. Valašské Meziříčí Expedice 25 2010-09-25 – 2010-11-26 Douglas H. Wheelock Sojuz TMA-19 • Odpojení: 2010-11-26 01:23:13 UTC Posádka ISS dočasně redukována na 3 osoby Sojuz TMA-19 • Odpojení: 2010-11-26 01:23:13 UTC • Přistání: 2010-11-26 04:46:53 UTC Posádka: Jurčichin, Walkerová, Wheelock Expedice 26 2010-11-26 – 2011-03-16 Scott J. Kelly Expedice 26 • Skripočka Kaleri Nespoli Kelly Kondrat’jev Colemanová Expedice 26 • CDR: Scott Joseph Kelly • FE1: Aleksandr Jurjevič Kaleri • FE2: Oleg Ivanovič Skripočka Sojuz TMA-20 Sojuz TMA-20 – posádka • KK: Dmitrij J. Kondratjev (RUS) 1 Sojuz TMA-20 – posádka • KK: Dmitrij J. Kondratjev (RUS) 1 • BI1: Catherine G. Coleman[ová] (USA) 3 Sojuz TMA-20 – posádka • KK: Dmitrij J. Kondratjev (RUS) 1 • BI1: Catherine G. Coleman[ová] (USA) 3 • BI2: Paolo A. Nespoli (ITA) 2 Colemanová Kondrat’jev Nespoli Sojuz TMA-20 • Start: 2010-12-15 19:09:25 UTC, Bajkonur PU-1/5 Nespoli Colemanová Kondrat’jev Sojuz TMA-20 • Start: 2010-12-15 19:09:25 UTC, Bajkonur PU-1/5 • Připojení: 2010-12-17 20:11:36 UTC, Rassvet Posádku ISS tvoříopět 6 osob Silvestr 2010/2011 HTV-2 „Kounotori“ • Start: 2011-01-22 05:37:57 UTC, Tanegašima, H-2B Progress M-08M • Start: 2010-10-27 15:11:50 UTC • Připojení: 2010-10-30 16:35:43 UTC, Pirs • Odpojení: 2011-01-24 00:42:43 UTC, Pirs Progress M-08M • Start: 2010-10-27 15:11:50 UTC • Připojení: 2010-10-30 16:35:43 UTC, Pirs -

The Battle for the Legality and Legitimacy of Ayahuasca Religions in Brazil Jennifer Ross Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU History Department Capstone and Seminar Papers 2012 The Battle for the Legality and Legitimacy of Ayahuasca Religions in Brazil Jennifer Ross Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation - Ross, Jennifer. "The Battle for the Legality and Legitimacy of Ayahuasca Religions in Brazil." Department of History seminar paper, - Western Oregon University, 2012. - This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone and Seminar Papers at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Department by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Battle for the Legality and Legitimacy of Ayahuasca Religions in Brazil By Jennifer Ross HST 600: Chile and Brazil December 12, 1012 Professor John L. Rector @ Jennifer Ross The Battle for the Legality and Legitimacy of Ayahuasca Religions in Brazil Ayahuasca is a hallucinogenic concoction that is said to have been used for thousands of years by various indigenous tribes who lived throughout the upper Amazon and Andes. The term Ayahuasca is a Quechua word meaning ‘vine of the souls’ or ‘vine of the dead’. The most common method for making Ayahuasca combines the bark of the liana vine Banisteriopsis Caapi with the leaves of the Psycotria Viridis; water is added and the mixture is boiled down to a brown-colored “tea”.1 The active ingredient in Ayahuasca that causes an altered state of consciousness is N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT). -

EWP 6537: ENTHEOGENIC SHAMANISM 3 Units Mondays 3 - 6 Pm, Room 307 Mission Building Spring, 2010

EWP 6537: ENTHEOGENIC SHAMANISM 3 Units Mondays 3 - 6 pm, Room 307 Mission building Spring, 2010 Instructor: Susana Bustos, Ph.D. (510) 987-6900 – [email protected] Course Description: This course explores the fundamentals of shamanic and shamanic-oriented traditions whose practices are based on working with sacred visionary plants. While a deeper focus is placed on Amazonian ayahuasca shamanism, an overview of traditions that use peyote, sacred mushrooms, and iboga lays the foundation for a participatory inquiry and discussion of common threads in entheogenic shamanism. A variety of disciplines and approaches to the topic inform the survey of basic themes, such as the functions of visionary plants in shamanic cultures, cosmology, ritual context and the use of music, healing practices, and the integration of experiences. Cultural, philosophical, and psychological questions are addressed throughout the course, for example, shadow aspects of entheogenic shamanic practices, the ontological status of visionary experiences, and the implications of the spread of entheogenic practices into the West. Learning Objectives: After completing this course, students will be able to: 1. Understand the traditional framework that sustains the use of entheogens in shamanic practices. 2. Be familiar with a variety of approaches to explaining the effectiveness of these practices. 3. Critically assess entheogenic practices, particularly within shamanic-oriented contexts. Learning Activities: • Lecture, videos 40% • Discussion, students’ presentations: 45% • Experiential: 15% Level of Instruction: Ph.D. / M.A. Criteria for Evaluation: 1. Mid-term paper (4-6 pages) 20% 2. Final paper (15-20 pages) 40% 3. Class participation and presentations 40% Pre-requisites: None. Grading Options: OP. -

2. the Notion of Cure in the Brazilian Ayahuasca Religions

T Transworld Research Network 37/661 (2), Fort P.O. Trivandrum-695 023 Kerala, India The Ethnopharmacology of Ayahuasca, 2011: 23-53 ISBN: 978-81-7895-526-1 Editor: Rafael Guimarães dos Santos 2. The notion of cure in the Brazilian ayahuasca religions Sandra Lucia Goulart Assistant Professor at Cásper Líbero College, São Paulo, Brazil and researcher in NEIP (Psychoactives Interdisciplinary Study Group), São Paulo, Brazil Abstract. This article discusses concepts and practices of healing in Brazilian religions which have in common the use of a psychoactive beverage mainly known by the names of Daime, Vegetal and Ayahuasca. These religions are elaborated from the same set of cultural traditions which nonetheless unfolds in different ways. All of them originate in the Brazilian Amazon region and in some cases, these processes expand to other parts of Brazil and abroad. We compare here the ways in which the healing is experienced and explained in these religions, emphasizing the representations concerning this beverage used in all of them. The case of these religions points to the complexity of the relation between both scientific and religious medicines. 1. Introduction In this article we intend to develop an analysis of the therapeutic concepts present in some religious cults emerged in the Brazilian Amazon region Correspondence/Reprint request: Dr. Sandra Lucia Goulart, Assistant Professor at Cásper Líbero College, São Paulo, Brazil and researcher in NEIP (Psychoactives Interdisciplinary Study Group), São Paulo, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] 24 Sandra Lucia Goulart starting from 1930. All these cults have in common the use of the same psychoactive beverage, made by brewing a combination of two plants, a liana whose scientific name is Banisteriopsis caapi and the leaves of a bush, Psychotria viridis1. -

Annual Report Sometimes Brutally

“Human rights defenders have played an irreplaceable role in protecting victims and denouncing abuses. Their commitment Steadfast in Protest has exposed them to the hostility of dictatorships and the most repressive governments. […] This action, which is not only legitimate but essential, is too often hindered or repressed - Annual Report sometimes brutally. […] Much remains to be done, as shown in the 2006 Report [of the Observatory], which, unfortunately, continues to present grave violations aimed at criminalising Observatory for the Protection and imposing abusive restrictions on the activities of human 2006 of Human Rights Defenders rights defenders. […] I congratulate the Observatory and its two founding organisations for this remarkable work […]”. Mr. Kofi Annan Former Secretary General of the United Nations (1997 - 2006) The 2006 Annual Report of the Observatory for the Protection Steadfast in Protest of Human Rights Defenders (OMCT-FIDH) documents acts of Foreword by Kofi Annan repression faced by more than 1,300 defenders and obstacles to - FIDH OMCT freedom of association, in nearly 90 countries around the world. This new edition, which coincides with the tenth anniversary of the Observatory, pays tribute to these women and men who, every day, and often risking their lives, fi ght for law to triumph over arbitrariness. The Observatory is a programme of alert, protection and mobilisation, established by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) in 1997. It aims to establish -

Mana for a New Age Rachel Morgain

11 Mana for a New Age Rachel Morgain From chakra healing to African drumming, sweat lodges to shamanic journeys, New Age movements, particularly in North America, are notorious for their pattern of appropriating concepts and practices from other spiritual traditions. While continental Native American and Asian influences are perhaps most familiar as sourcing grounds for New Age material, the traditions of Pacific Islanders, particularly Hawaiians, have not escaped New Age attention. In particular, the movement known as ‘Huna’ has introduced Hawaiian-sounding words and concepts to the New Age vocabulary. Chief among these is the concept of ‘mana’, controversially subsumed within what is often a large laundry list of non-western religious and philosophical nomenclature, under the generic category of ‘energy’ or ‘life force’. Continually adapted through succeeding generations of Huna teachings, and further adopted into sections of the related contemporary Pagan movement through the tradition known as ‘Feri’, the concept of ‘mana’ displays some consistent themes across these traditions, quite different from its meaning in Hawaiian contexts. In being adopted into these movements, it has been transformed to fit within a field of ideas that have developed in western esoteric traditions from at least the late eighteenth century. In this chapter, I trace some of the ideas that have come to be attached to the concept of mana through several iterations of New Age movements in North America. Beginning with the foundational 285 NEW MANA works of Max Freedom Long, I look at the spiritual practice known as Huna, popularised from the late 1930s through a series of Long’s texts and his Huna Research organisation. -

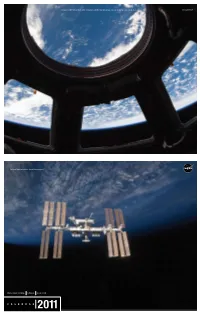

C a L E N D a R International Space Station

For more information on the International Space Station, visit: www.nasa.gov/station visit: Station, Space International the on information more For www.nasa.gov National Aeronautics and Space Administration INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION CALENDAR 2011 A MESSAGE FROM THE PROGRAM MANAGER The International Space Station (ISS) is one of the greatest technological, geopolitical and engineering accomplishments in human 2011 history. The completion of the ISS on-orbit assembly allows for a focus on the multifaceted purpose of the ISS, one of scientific research, technology development, exploration and education. As a National Laboratory, the ISS will provide opportunities beyond NASA to academia, commercial entities and other government agencies to pursue their research and development needs in science, technology development and education. With everyone working together, we look forward to extending human presence beyond and improving life here on Earth. This calendar is designed to show all facets of the ISS using displays of astounding imagery and providing significant historical events with the hope of inspiring the next generation. NASA is appreciative of the commitment that America’s educators demonstrate each and every day as they instruct and shape the young students who will be tomorrow’s explorers and leaders. I hope you enjoy the calendar and are encouraged to learn new and exciting aspects about NASA and the ISS throughout the year. Regards, MICHAEL T. SUFFREDINI ISS Program Manager 1 2 2 3 4 6 5 LOOK HOW FAR WE’VE COME 20 JANUARY NASA has powered us into the 21st century through signature 11 accomplishments that are enduring icons of human achievement.