Effects of Small-Scale Armoring and Residential Development on the Salt Marsh-Upland Ecotone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Systematics and Ecology of the Mangrove-Dwelling Littoraria Species (Gastropoda: Littorinidae) in the Indo-Pacific

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Reid, David Gordon (1984) The systematics and ecology of the mangrove-dwelling Littoraria species (Gastropoda: Littorinidae) in the Indo-Pacific. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/24120/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/24120/ THE SYSTEMATICS AND ECOLOGY OF THE MANGROVE-DWELLING LITTORARIA SPECIES (GASTROPODA: LITTORINIDAE) IN THE INDO-PACIFIC VOLUME I Thesis submitted by David Gordon REID MA (Cantab.) in May 1984 . for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Zoology at James Cook University of North Queensland STATEMENT ON ACCESS I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that the following restriction placed by me on access to this thesis will not extend beyond three years from the date on which the thesis is submitted to the University. I wish to place restriction on access to this thesis as follows: Access not to be permitted for a period of 3 years. After this period has elapsed I understand that James Cook. University of North Queensland will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other photographic means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All uses consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: 'In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which I have obtained from it.' David G. -

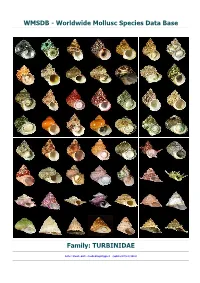

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Diamondback Terrapin Malaclemys Terrapin Contributors: Dubose Griffin, David Owens and J

Diamondback Terrapin Malaclemys terrapin Contributors: DuBose Griffin, David Owens and J. Whitfield Gibbons DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Description The diamondback terrapin is a small, long-lived estuarine turtle endemic to coastal marshes, estuarine bays, lagoons and creeks ranging from Cape Cod, Massachusetts to the Gulf Coast of Texas. Currently, there are five (Hartsell 2001) or seven (Ernst et al. 1994) subspecies. More recently, Hart (2004) identified six management units. The subspecies found in South Carolina is Malaclemys terrapin centrata. Terrapins have varied coloration from black to spotted patterns on the soft tissue and dark or light-colored scutes with strong concentric layers on the carapace. The hind margin of the carapace curls up instead of flaring. Hind legs are large and toes have extensive webs. These turtles are strong, fast swimmers that feed on a variety of mollusks, crustaceans and other invertebrates. In South Carolina, salt marsh periwinkles (Littoraria irrorata) and blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) are among the terrapin’s primary food sources (Tucker et al. 1995; Levesque 2000). Terrapins are sexually dimorphic. Females are much larger than males and reach 15 to 18 cm (6 to7 inches) in length; males reach 10 to 13 cm (4 to 5 inches) in length. Adult females also have enlarged heads. Terrapins hibernate in the mud during winter and mate in the spring. Eggs are laid May through early August and clutches have 5 to 12 eggs (Pritchard 1979). The number of clutches laid per female in South Carolina is undocumented; however two clutches may be common (David Owens, College of Charleston, pers. -

2019-2020 CRMEP.Pdf

CURRENT RESEARCH PROJECTS 2019 – 2020 Baruch Marine Field Laboratory North Inlet-Winyah Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve University of South Carolina Belle W. Baruch Institute North Inlet-Winyah Bay for Marine & Coastal Sciences National Estuarine Research Reserve Current Research Projects 2019 – 2020 Introduction The Baruch Marine Field Laboratory (BMFL), located on Hobcaw Barony in Georgetown County, has been the center of research activities for scientists and students from the University of South Carolina (USC) and dozens of other institutions since 1969. We conservatively estimate that between senior scientist projects and masters and doctoral studies conducted by graduate students, more than 1,000 grant and institutionally-funded projects have taken place at BMFL. This work has contributed substantially to the more than 2,000 peer-reviewed scientific articles, books, and technical reports that have been published since the Baruch Institute was founded. Independent and multi-disciplinary studies have been conducted by biologists, chemists, geologists, oceanographers, and other specialists who share interests in the structure, function, and condition of coastal environments. Results of research projects are used by educators, coastal resource managers, health and environmental regulators, legislators, and many other individuals and organizations interested in maintaining and improving the condition of estuaries in the face of increasing human activities and changing climate in the coastal zone. The following annotated list summarizes 89 projects that were underway during the period from July 2019 through December 2020 in the North Inlet and Winyah Bay estuaries by faculty, staff, graduate students, and undergraduates associated with the USC and other institutions. USC is the home institution for 54 of the investigators while over 78 investigators representing 35 other institutions and agencies are carrying out projects through BMFL. -

Marsh Periwinkle Habitat for Many Species of and JOURNEY THROUGH Fishes, and Other Animals, Such

NATURALIST’S NOTEBOOK Moving Through the Marsh BY REBECCA NAGY • NORTH CAROLINA’S AMAZING COAST ILLUSTRATIONS BY CHARLOTTE INGRAM COLD OUTSIDE? in and out. They also provide THEPRETEND IT’S SUMMER MARSHMarsh Periwinkle habitat for many species of AND JOURNEY THROUGH fishes, and other animals, such A COASTAL SALT MARSH. Common to North Carolina’s as the marsh periwinkle. LEARN ABOUT THIS salt marshes, the marsh • Smooth cordgrass, periwinkle is no flower HABITAT NOW AND but instead is a or Spartina alterniflora, is the member of a group BE THAT MUCH MORE of marine gastropod predominant plant in North mollusks that are KNOWLEDGEABLE WHEN characterized by Carolina’s salt marshes. This their conical, THE WARMER WEATHER spiraling shells. salt-tolerant plant makes ROLLS AROUND. At low tide these snails the marsh look like a “sea of can be found at the base of The salt marsh is a fascinating one of their favorite foods, the grass.” The plant can grow as smooth cordgrass, Spartina habitat teeming with creatures alterniflora, which is the tall as 8 feet. At high tide, the predominant plant in big and small. These plants and North Carolina marshes. marsh periwinkle sneaks up the animals depend on — and thrive However, as the tide rises, so does base of the smooth cordgrass the periwinkle. Up the cordgrass stalk it in — the mixture of salt and fresh goes, where in turn, it sometimes becomes toward the top to escape rising food for sharp-eyed egrets and herons. water that continually flows in and water, and predators such as out of the area. -

English Cop16 Prop. 31 CONVENTION ON

Original language: English CoP16 Prop. 31 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Sixteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Bangkok (Thailand), 3-14 March 2013 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Inclusion of Malaclemys terrapin in Appendix II; in accordance with Article II, paragraph 2 (a) of the Convention and Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP15), Annex 2a as per: a) Criteria A. It is known, or can be inferred or projected, that the regulation of trade in the species is necessary to avoid it becoming eligible for inclusion in Appendix I in the near future; and b) Criteria B. It is known, or can be inferred or projected, that regulation of trade in the species is required to ensure that the harvest of specimens from the wild is not reducing the wild population to a level at which its survival might be threatened by continued harvesting or other influences. B. Proponent United States of America * C. Supporting statement 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Reptilia 1.2 Order: Testudines 1.3 Family: Emydidae 1.4 Species: Malaclemys terrapin (Schoepff 1793) 1.5 Scientific synonyms: Testudo terrapin (Schoepff 1793) Holbrook, 1842 Testudo concentrica (Shaw 1802) Testudo ocellata (Link 1807) Testudo concentrata (Kuhl 1820) Testudo concentrica [var.] (Gray 1831) Emys concentrica (Dumeril & Bibron 1835) Emys macrocephalus (Gray 1844) Emys concentrica (Dumeril & Bibron 1854) Malaclemys concentrica (Gray 1863) Malacoclemmys terrapen (Boulenger 1889) Malaclemys terrapin (Bangs 1896) * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Temperature and Relative Humidity Effects on Water Loss and Hemolymph Osmolality of Littoraria Angulifera (Lamarck, 1822)

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV UTB/UTPA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Legacy Institution Collections 4-2014 Temperature and relative humidity effects on water loss and hemolymph osmolality of Littoraria angulifera (Lamarck, 1822) Phillip J. Rose The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/leg_etd Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Phillip J., "Temperature and relative humidity effects on water loss and hemolymph osmolality of Littoraria angulifera (Lamarck, 1822)" (2014). UTB/UTPA Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 39. https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/leg_etd/39 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Legacy Institution Collections at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in UTB/UTPA Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Temperature and Relative Humidity Effects on Water Loss and Hemolymph Osmolality of Littoraria angulifera (Lamarck, 1822) A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of Science, Mathematics and Technology University of Texas at Brownsville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In the field of Biology by Phillip J. Rose April 2014 Copyright By Phillip J. Rose April 2014 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and especially thank the many people who assisted and/or contributed to this project in some way, shape, or form…………..and there were many! First, I would like to say a big thank you to the thesis committee comprised of Dr. -

Diamondback Terrapin Malaclemys Terrapin

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Diamondback Terrapin Malaclemys terrapin Contributors (2005): Erin Levesque (SCDNR), J. Whitfield Gibbons (SREL), DuBose Griffin (SCDNR), David Owens (College of Charleston) Reviewed and Edited (2012): Erin Levesque (SCDNR) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Description The diamondback terrapin is a small, long-lived estuarine turtle endemic to coastal marshes, estuarine bays, lagoons and creeks ranging from Cape Cod, Massachusetts to the Gulf Coast of Texas. Currently, there are 5 (Hartsell 2001) or 7 (Ernst et al. 1994) subspecies. More recently, Hart (2004) identified six management units. The subspecies found in South Carolina is Malaclemys terrapin centrata. Terrapins have varied coloration from black to spotted patterns on the soft tissue and dark or light-colored scutes with strong concentric layers on the carapace. The hind margin of the carapace curls up instead of flaring. Hind legs are large and toes have extensive webs. These turtles are strong, fast swimmers that feed on a variety of mollusks, crustaceans and other invertebrates. In South Carolina, salt marsh periwinkles (Littoraria irrorata) and blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) are among the terrapin’s primary food sources (Tucker et al. 1995; Levesque 2000). Terrapins are sexually dimorphic. Females are much larger than males and reach 15 to 18 cm (6 to7 in.) in length; males reach 10 to 13 cm (4 to 5 in.) in length. Adult females also have enlarged heads. Terrapins hibernate in the mud during winter and mate in the spring. Eggs are laid May through early August and clutches have 5 to 12 eggs (Pritchard 1979). -

Recovery of the Salt Marsh Periwinkle (Littoraria Irrorata) 9 Years After the T Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill: Size Matters ⁎ Donald R

Marine Pollution Bulletin 160 (2020) 111581 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Pollution Bulletin journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul Recovery of the salt marsh periwinkle (Littoraria irrorata) 9 years after the T Deepwater Horizon oil spill: Size matters ⁎ Donald R. Deisa, , John W. Fleegerb, David S. Johnsonc, Irving A. Mendelssohnd, Qianxin Lind, Sean A. Grahame, Scott Zengelf, Aixin Houg a Atkins, Jacksonville, FL 32256, USA b Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA c Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary, Gloucester Point, VA 23062, USA d Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA e Gulf South Research Corporation, Baton Rouge, LA 70820, USA f Research Planning, Inc., Tallahassee, FL 32303, USA g Department of Environmental Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Prior studies indicated salt marsh periwinkles (Littoraria irrorata) were strongly impacted in heavily oiled Littoraria irrorata marshes for at least 5 years following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Here, we detail longer-term effects and Salt marsh recovery over nine years. Our analysis found that neither density nor population size structure recovered at Marsh periwinkle heavily oiled sites where snails were smaller and variability in size structure and density was increased. Total Deepwater Horizon oil spill aboveground live plant biomass and stem density remained lower over time in heavily oiled marshes, and we Ecological impacts speculate that the resulting more open canopy stimulated benthic microalgal production contributing to high Ecological recovery spring periwinkle densities or that the lower stem density reduced the ability of subadults and small adults to escape predation. -

Mollusks Taken by Beam Trawl in the Vicinity of Gray's Reef National Marine Sanctuary on the Continental Shelf Off Georgia, Southeastern US

Mollusks taken by Beam Trawl in the vicinity of Gray's Reef National Marine Sanctuary on the Continental Shelf off Georgia, Southeastern U.S. Item Type monograph Authors Wolfe, Dougals A. Publisher NOAA/National Ocean Service/National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science/Center for Coastal Fisheries and Habitat Research Download date 26/09/2021 22:59:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/19903 Mollusks taken by Beam Trawl in the vicinity of Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary on the Continental Shelf off Georgia, Southeastern U.S. NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 88 Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for their use by the United States government. Citation for this Report Wolfe, Douglas A. 2008. Mollusks taken by Beam Trawl in the vicinity of Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary on the Continental Shelf off Georgia, Southeastern U.S. NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 88. 40 pp. Mollusks taken by Beam Trawl in the vicinity of Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary on the Continental Shelf off Georgia, Southeastern U.S. Douglas A. Wolfe* NOAA, National Ocean Service National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science Center for Coastal Fisheries and Habitat Research NOAA Beaufort Laboratory 101 Pivers Island Road Beaufort, North Carolina 28516 *(retired) Present address: 109 Shore Drive, Beaufort, NC 28516 NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 88 December, 2008 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………….. iii Introduction…………………………………………………………………. 1 Methods………………………………………………………………….….. 2 Results………………………………………………………………….……. 4 Sample Characteristics………………………………………….…….. 4 Total Numbers of Taxa………………………………………….……. 6 Species Associations and Community Composition……….….….….. 7 Effect of Depth……………………………………………….…. 7 The “Atrina-Cymatium” Community………………………...… 10 Thee Nassarius acutus-Phascolion-Pythinella Connection…… 11 Rock-Dwelling Species………………………………………… 13 Range Extensions…………………………………………….………. -

Density, Shell Use and Species Composition of Juvenile Fiddler Crabs (Uca Spp.) at Low and High Impact Salt Marshes on Georgia Barrier Islands

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Fall 2011 Density, Shell Use and Species Composition of Juvenile Fiddler Crabs (Uca Spp.) at Low and High Impact Salt Marshes on Georgia Barrier Islands Michelle D. Carlson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Carlson, Michelle D., "Density, Shell Use and Species Composition of Juvenile Fiddler Crabs (Uca Spp.) at Low and High Impact Salt Marshes on Georgia Barrier Islands" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 756. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/756 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT DENSITY, SHELL USE AND SPECIES COMPOSITION OF JUVENILE FIDDLER CRABS ( UCA SPP.) AT LOW AND HIGH IMPACT SALT MARSHES ON GEORGIA BARRIER ISLANDS by MICHELLE D. CARLSON (Under the Direction of Sophie B. George and Laura B. Regassa) Coastal wetlands offer refuge for juveniles of many species, with protection often coming in the form of dense vegetation. Human impacts have led to a 67% loss of coastal wetlands worldwide in the past 300 years, thus decreasing available refuges. There are no studies that show what affect this has on fiddler crabs ( Uca spp.), a key species in salt marsh habitats. The present study looks at how human impacts are affecting juvenile fiddler crab densities, shell use, and species compositions. -

Littorinidae

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: LITTORINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: CAENOGASTROPODA-HYPSOGASTROPODA-LITTORINIMORPHA-LITTORINOIDEA ------ Family: LITTORINIDAE Children, 1834 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=959, Genus=31, Subgenus=11, Species=239, Subspecies=16, Synonyms=661, Images=178 aberrans , Littoraria aberrans (R.A. Philippi, 1846) abjecta, Echinolittorina abjecta A. Adams, 1852 - syn of: Echinolittorina atrata (A. Adams, 1852) abyssicola, Lacuna abyssicola J.C. Melvill & R. Standen, 1912 abyssorum , Lacuna abyssorum É.A.A. Locard, 1896 - syn of: Benthonella tenella (J.G. Jeffreys, 1869) acuminata , Littorina acuminata A.A. Gould, 1849 - syn of: Littoraria undulata (J.E. Gray, 1839) acuta , Austrolittorina acuta R.A. Philippi, 1847 - syn of: Austrolittorina unifasciata (J.E. Gray, 1826) acutispira , Afrolittorina acutispira (E.A. Smith, 1892) acutispira , Nodilittorina acutispira E.A. Smith, 1892 - syn of: Afrolittorina acutispira (E.A. Smith, 1892) adonis , Palustorina adonis M. Yokoyama, 1927 - syn of: Littoraria sinensis (R.A. Philippi, 1847) adonis , Littorina adonis M. Yokoyama, 1927 - syn of: Littoraria sinensis (R.A. Philippi, 1847) aestualis , Laevilitorina aestualis H. Strebel, 1908 - syn of: Laevilitorina caliginosa (A.A. Gould, 1849) affinis , Tectarius affinis D'Orbigny, 1839 - syn of: Tectarius striatus (P.P. King, 1832) affinis , Littorina affinis D'Orbigny, 1840 - syn of: Tectarius striatus (P.P. King, 1832) africana , Afrolittorina africana (C.F.F. von Krauss in R.A. Philippi, 1847) africana , Nodilittorina africana C.F.F. von Krauss in R.A. Philippi, 1847 - syn of: Afrolittorina africana (C.F.F. von Krauss in R.A.