Spatial Distribution of Dominant Arboreal Ants in a Malagasy Coastal Rainforest: Gaps and Presence of an Invasive Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technomyrmex Albipes (360)

Pacific Pests, Pathogens and Weeds - Online edition White-footed ant - Technomyrmex albipes (360) Summary Worldwide distribution. In Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Guam, Marshall Islands, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Wallis and Futuna. Three similar white- footed species, needing specialist identification. Common in Pacific island countries. Major pest. Damage to plants indirect: protects natural enemies from attacking aphids, mealybugs, scales, whiteflies, encouraging outbreaks. Nests of debris on ground, in trees, in houses. Does not bite humans. Males, winged and wingless; three kinds females (queens, workers, 'intercastes'). Queens mate, establish colony; later, reproductive (fertilised) intercastes later take over. Foraging Photo 1. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex by (unfertilised) workers - living/dead insects, honeydew, own eggs. species, tending an infestation of Icerya Tramp ant; spread by 'budding' - intercastes leave nest with workers, males and brood; seychellarum on avocado for their honeydew. spread with international trade. Biosecurity: requires risk assessments, regulations preventing introduction, protocols in case of breaches, and ability to make rapid response. Pacific Ant Prevention Plan available (IUCN/SSC Invasive Specialist Group). Cultural control: hot water at 47°C kills ants; over 49°C kills plants. Chemical control: use (i) stomach poisons (fibronil, Amdro®, borax), (ii) growth regulators (methoprene, pyriproxyfen), (iii) nerve poisons (bifenthrin, fipronil, imidacloprid). See (http://piat.org.nz/index.php?page=getting-rid-of-ants). Common Name Photo 2. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex species, tending an infestation of mealybugs White-footed ant; white-footed house ant. on noni (Morinda citrifolia) for their honeydew. Scientific Name Technomyrmex albipes. -

Appendix 7-1: Summary of South Florida's Nonindigenous Species

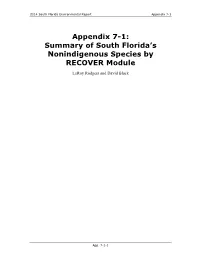

2014 South Florida Environmental Report Appendix 7-1 Appendix 7-1: Summary of South Florida’s Nonindigenous Species by RECOVER Module LeRoy Rodgers and David Black App. 7-1-1 Appendix 7-1 Volume I: The South Florida Environment Table 1. Summary of South Florida’s nonindigenous animal species and Category I invasive plant species by RECOVER module.1 KY SE GE BC NW NE LO KR Amphibians *Bufo marinus Giant toad x x x x x x x x Eleutherodactylus planirostris Greenhouse frog x x x x x x x x *Osteopilus septentrionallis Cuban treefrog x x x x x x x x Reptiles Agama agama African redhead agama x x x x x Ameiva ameiva Giant ameiva x x Anolis chlorocyanus Hispaniolan green anole x x x Anolis cristatellus cristatellus Puerto Rican crested anole x Anolis cybotes Largehead anole x x x *Anolis distichus Bark anole x x x x x x x *Anolis equestris equestris Knight anole x x x x x x x x Anolis extremus Barbados anole x *Anolis garmani Jamaican giant anole x x x x x Anolis porcatus Cuban green anole x x *Anolis sagrei Brown anole x x x x x x x x Basiliscus vittatus Brown basilisk x x x x x x x *Boa constrictor Common boa x Caiman crocodilus Spectacled caiman x x x Calotes mystaceus Indochinese tree agama x x Table Key KY = Keys NW = Northern Estuaries West Green Found in one module SE = Southern Estuaries NE = Northern Estuaries East Orange Found in all modules GE = Greater Everglades LO = Lake Okeechobee Blue Found in all but one module BC = Big Cypress KR = Kissimmee River Pink Status changed since 2011 *Species that make significant use of less disturbed portions of the module. -

Worldwide Spread of the Difficult White-Footed Ant, Technomyrmex Difficilis (Hymeno- Ptera: Formicidae)

Myrmecological News 18 93-97 Vienna, March 2013 Worldwide spread of the difficult white-footed ant, Technomyrmex difficilis (Hymeno- ptera: Formicidae) James K. WETTERER Abstract Technomyrmex difficilis FOREL, 1892 is apparently native to Madagascar, but began spreading through Southeast Asia and Oceania more than 60 years ago. In 1986, T. difficilis was first found in the New World, but until 2007 it was mis- identified as Technomyrmex albipes (SMITH, 1861). Here, I examine the worldwide spread of T. difficilis. I compiled Technomyrmex difficilis specimen records from > 200 sites, documenting the earliest known T. difficilis records for 33 geographic areas (countries, island groups, major islands, and US states), including several for which I found no previously published records: the Bahamas, Honduras, Jamaica, the Mascarene Islands, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Africa, and Washington DC. Almost all outdoor records of Technomyrmex difficilis are from tropical areas, extending into the subtropics only in Madagascar, South Africa, the southeastern US, and the Bahamas. In addition, there are several indoor records of T. dif- ficilis from greenhouses at zoos and botanical gardens in temperate parts of the US. Over the past few years, T. difficilis has become a dominant arboreal ant at numerous sites in Florida and the West Indies. Unfortunately, T. difficilis ap- pears to be able to invade intact forest habitats, where it can more readily impact native species. It is likely that in the coming years, T. difficilis will become increasingly more important as a pest in Florida and the West Indies. Key words: Biogeography, biological invasion, exotic species, invasive species. Myrmecol. News 18: 93-97 (online 19 February 2013) ISSN 1994-4136 (print), ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Received 28 November 2012; revision received 7 January 2013; accepted 9 January 2013 Subject Editor: Florian M. -

Technomyrmex Difficilis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the West Indies

428 Florida Entomologist 91(3) September 2008 TECHNOMYRMEX DIFFICILIS (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) IN THE WEST INDIES JAMES K. WETTERER Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University, 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458 ABSTRACT Technomyrmex difficilis Forel is an Old World ant often misidentified as the white-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes (Smith). The earliest New World records of T. difficilis are from Miami-Dade County, Florida, collected beginning in 1986. Since then, it has been found in at least 22 Florida counties. Here, I report T. difficilis from 5 West Indian islands: Antigua, Nevis, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, and St. Thomas. Colonies were widespread only on St. Croix. It is probable that over the next few years T. difficilis will become increasingly important as a pest in Florida and the West Indies. Key Words: exotic species, Technomyrmex difficilis, pest ants, West Indies RESUMEN El Technomyrmex difficilis Forel es una hormiga del Mundo Antiguo que a menudo es mal identificada como la hormiga de patas blancas, Technomyrmex albipes (Smith). Los registros mas viejos de T. difficilis son del condado de Miami-Dade, Florida, recolectadas en el princi- pio de 1986. Desde entonces, la hormiga ha sido encontrada en por lo menos 22 condados de la Florida. Aquí, informo de la presencia de T. difficilis en 5 islas del Caribe: Antigua, Nevis, Puerto Rico, St. Croix y St. Thomas. Las colonias solamente fueron muy exparcidas en St. Croix. Es probable que la importancia de T. difficilis como plaga va a aumentar durante los proximos años en la Florida y el Caribe. The white-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes MATERIALS AND METHODS (Smith), has long been considered a pest in many parts of the world. -

Ants - White-Footed Ant (360)

Pacific Pests and Pathogens - Fact Sheets https://apps.lucidcentral.org/ppp/ Ants - white-footed ant (360) Photo 1. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex species, Photo 2. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex species, tending an infestation of Icerya seychellarum on tending an infestation of mealybugs on noni (Morinda avocado for their honeydew. citrifolia) for their honeydew. Photo 3. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes, side Photo 4. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes, view. from above. Photo 5. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes; view of head. Common Name White-footed ant; white-footed house ant. Scientific Name Technomyrmex albipes. Identification of the ant requires expert examination as there are several other species that are similar. Many specimens previously identified as Technomyrmex albipes have subsequently been reidentified as Technomyrmex difficilis (difficult white-footed ant) or as Technomyrmex vitiensis (Fijian white-footed ant), which also occurs worldwide. Distribution Worldwide. Asia, Africa, North and South America (restricted), Caribbean, Europe (restricted), Oceania. It is recorded from Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Guam, Marshall Islands, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Wallis and Futuna. Hosts Tent-like nests made of debris occur on the ground within leaf litter, under stones or wood, among leaves of low vegetation, in holes, crevices and crotches of stems and trunks, in the canopies of trees, and on fruit. The ants also make nests in wall cavities of houses, foraging in kitchens and bathrooms. Symptoms & Life Cycle Damage to plants is not done directly by Technomyrmex albipes, but indirectly. The ants feed on honeydew of aphids, mealybugs, scale insects and whiteflies, and prevent the natural enemies of these pests from attacking them. -

Evolution of Colony Characteristics in the Harvester Ant Genus

Evolution of Colony Characteristics in The Harvester Ant Genus Pogonomyrmex Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Christoph Strehl Nürnberg Würzburg 2005 - 2 - - 3 - Eingereicht am: ......................................................................................................... Mitglieder der Prüfungskommission: Vorsitzender: ............................................................................................................. Gutachter : ................................................................................................................. Gutachter : ................................................................................................................. Tag des Promotionskolloquiums: .............................................................................. Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am: ............................................................................. - 4 - - 5 - 1. Index 1. Index................................................................................................................. 5 2. General Introduction and Thesis Outline....................................................... 7 1.1 The characteristics of an ant colony...................................................... 8 1.2 Relatedness as a major component driving the evolution of colony characteristics.................................................................................................10 1.3 The evolution -

WHITEFOOTED ANT Scientific Names: Technomyrmex Albipes, T

WHITEFOOTED ANT Scientific names: Technomyrmex albipes, T. difficilis, T. vitiensis Order: Hymenoptera Family: Formicidae Common name: whitefooted ant DESCRIPTION Adults have different body types according to their role in the colony . Adult workers are females, wingless, 2 to 4 mm (< ¼ “) long, and dull black with yellowish‐white lower legs. Queens are larger, winged early in life, and lay fertile and infertile eggs Actual size throughout their lives. Males are wingless, short‐lived, and function only in reproduction. DAMAGE . Damage by whitefooted ants (WFA) is usually indirect since they tend honeydew‐producing insects (mealybugs, aphids, soft scales, whiteflies), protecting them from control by natural enemies. Although WFA are strongly attracted to sweet foods, such as plant nectar and honeydew, they also feed on decaying plant and animal tissue. WFA are a nuisance to homeowners as they forage indoors and outdoors, attracted by food and electrical contacts. LIFE CYCLE / BEHAVIOR The lifespan of worker ants is not known, but queens can live more than a year. Eggs are tiny (.5 mm), white or yellowish , oval, and are found, along with other developmental stages, in the nest constructed of dirt and plant debris (such as red ginger flowers). Young larvae are legless, pale, and shaped like a crook‐ necked gourds (heads at smaller, narrow end). Larvae develop into pupae without cocoons; both pupae and larvae are often mistaken for eggs. Whitefooted ants are very difficult to control because they do not exchange baits orally. If the majority of workers feed on the bait and die, the rest of the colony will eventually die of starvation. -

Ecology of Some Lesser-Studied Introduced Ant Species in Hawaiian Forests

Ecology of some lesser-studied introduced ant species in Hawaiian forests Paul D. Krushelnycky Journal of Insect Conservation An international journal devoted to the conservation of insects and related invertebrates ISSN 1366-638X J Insect Conserv DOI 10.1007/s10841-015-9789-y 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer International Publishing Switzerland. This e- offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self-archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy J Insect Conserv DOI 10.1007/s10841-015-9789-y ORIGINAL PAPER Ecology of some lesser-studied introduced ant species in Hawaiian forests Paul D. Krushelnycky1 Received: 18 May 2015 / Accepted: 11 July 2015 Ó Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 Abstract Invasive ants can have strong ecological effects suggest that higher densities of these introduced ant species on native arthropods, but most information on this topic could result in similar interactions with arthropods as those comes from studies of a handful of ant species. The eco- of the better-studied invasive ant species. -

The Influence of Ants on the Insect Fauna of Broad

THE INFLUENCE OF ANTS ON THE INSECT FAUNA OF BROAD - LEAVED, SAVANNA TREES. by SUSAN GRANT Thesis submitted to Rhodes University in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Science Department of Zoology and Entomology Rhodes University Grahamstown SOUTH AFRICA May 1984 TO MY PARENTS AND SISTER, ROSEMARY ---- '.,. ... .... ...... ;; ............. .... :.:..:.: " \ ... .:-: ..........~.~ . .... ~ ... .... ......... • " ".! . " \ ......... :. ........ .................... FRONTISPIECE TOP RIGHT - A map of Southern Africa indicating the position of the Nylsvley Provincial Nature Reserve. TOP LEFT One of the dominant ant species, Crematogaster constructor, housed in a carton nest in a Terminalia sericea tree. R BOTTOM RIGHT - A sticky band of Formex which was applied to the trunk of trees to exclude ants. BOTTOM LEFT - Populations of the scale insect Ceroplastes rusci on the leaves of an unbanded Ochna pulchra shrub. CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1. ABSTRACT 2. INTRODUCTION 1 - 4 3. STUDY AREA 5 - 10 3.1 Abiotic components 3.2 Biotic components 4. GENERAL MATERIALS AND METHODS 11 - 14 4.1 Ant exclusion 4.2 Effect of banding 5. THE RESULTS OF BANDING 15 - 17 5.1 Effect on plant phenology 5.2 Effect on the insect fauna 6. THE ANT COMMUNITY 18 - 29 6.1 The ant species 6.2 Ant distribution and nesting sites 6.3 Field observations 7. SAMPLING OF BANDED AND UNBANDED TREES 30 - 44 7.1 Non-destructive sampling 7.2 Destructive pyrethrum sampling 8. ASSESSMENT OF HERBIVORY 45 - 55 8.1 Damage records on .banded and unbanded trees 9. DISCUSSION 56 - 60 APPENDICES 61 - 81 REFERENCES 82 - 90 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere thanks to Professor V.C. -

California Agriculture Detector Dog Team Program Annual Report 2013

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURE DETECTOR DOG TEAM PROGRAM Annual Report July 1, 2013 • June 30, 2014 Pictured: San Joaquin County Dog Team Tom Doud and Kojak. Photo courtesy of San Joaquin County Agricultural Commissioner Office. Cooperative Agreement #13-8506-1165-CA Purpose of Cooperative Agreement #13-8506-1165-CA The purpose of cooperative agreement USDA #13-8506-1165-CA is to implement the use of the California Agriculture Detector Dog Teams (herein referenced as California Dog Teams) to enhance inspection and surveillance activities related to plant products entering the State of California via parcel delivery facilities and airfreight terminals for the purpose of excluding the introduction of plant pests that may negatively impact agriculture. Work Plan Activities Performed by CDFA CDFA oversaw and provided guidance for the statewide California Dog Team Program and distributed funds through cooperative agreements to County Agricultural Commissioners (CAC) for the purposes of fulfilling California Dog Team activities as outlined in the CDFA/CAC cooperative agreement. CDFA verified all expenses approved for payment to county agricultural commissioner cooperators were legitimate expenses as outlined in the CDFA/CAC cooperative agreement. CDFA acted as the liaison between CAC and the National Detector Dog Training Center (NDDTC) and was responsible for communicating significant pest finds and smuggling information to USDA/SITC. Work Plan Activities Performed by County Agricultural Commissioners The California Dog Teams were distributed as outlined in Table 1 below. Seven of the thirteen California Dog Teams worked parcel facilities for the full reporting period (July 1, 2013 - June 30, 2014): Alameda (1 team), Fresno (1 team), Los Angeles (1 team), Sacramento (1 team), San Bernardino (1 team), San Diego (1 team), and Santa Clara (1 team). -

The Tramp Ant Technomyrmex Vitiensis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) on South America Author(S): Jacques H.C

The Tramp Ant Technomyrmex vitiensis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) on South America Author(s): Jacques H.C. Delabie, Sarah Groc and Alain Dejean Source: Florida Entomologist, 94(3):688-689. Published By: Florida Entomological Society DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1653/024.094.0335 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1653/024.094.0335 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. 688 Florida Entomologist 94(3) September 2011 THE TRAMP ANT TECHNOMYRMEX VITIENSIS (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE: DOLICHODERINAE) ON SOUTH AMERICA JACQUES H.C. DELABIE1,2, SARAH GROC3 AND ALAIN DEJEAN3,4 1Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz. Rodovia Ilhéus-Itabuna, Km 16, 45650-000 Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil 2U.P.A. Laboratório de Mirmecologia, Convênio CEPEC/UESC, Centro de Pesquisas do Cacau, CEPLAC, Cx.P. 7, 45600-000 Itabuna, Bahia, Brazil 3CNRS; Écologie des Forêts de Guyane (UMR-CNRS 8172), BP 709, 97387 Kourou cedex, France 4Université de Toulouse; UPS; 118 route de Narbonne, F-31062 Toulouse, France Invasive ants are among the most harmful and terer 2008). -

Trophallaxis: the Functions and Evolution of Social Fluid Exchange in Ant Colonies (HymenoPtera: Formicidae) Marie-Pierre Meurville & Adria C

ISSN 1997-3500 Myrmecological News myrmecologicalnews.org Myrmecol. News 31: 1-30 doi: 10.25849/myrmecol.news_031:001 13 January 2021 Review Article Trophallaxis: the functions and evolution of social fluid exchange in ant colonies (Hymeno ptera: Formicidae) Marie-Pierre Meurville & Adria C. LeBoeuf Abstract Trophallaxis is a complex social fluid exchange emblematic of social insects and of ants in particular. Trophallaxis behaviors are present in approximately half of all ant genera, distributed over 11 subfamilies. Across biological life, intra- and inter-species exchanged fluids tend to occur in only the most fitness-relevant behavioral contexts, typically transmitting endogenously produced molecules adapted to exert influence on the receiver’s physiology or behavior. Despite this, many aspects of trophallaxis remain poorly understood, such as the prevalence of the different forms of trophallaxis, the components transmitted, their roles in colony physiology and how these behaviors have evolved. With this review, we define the forms of trophallaxis observed in ants and bring together current knowledge on the mechanics of trophallaxis, the contents of the fluids transmitted, the contexts in which trophallaxis occurs and the roles these behaviors play in colony life. We identify six contexts where trophallaxis occurs: nourishment, short- and long-term decision making, immune defense, social maintenance, aggression, and inoculation and maintenance of the gut microbiota. Though many ideas have been put forth on the evolution of trophallaxis, our analyses support the idea that stomodeal trophallaxis has become a fixed aspect of colony life primarily in species that drink liquid food and, further, that the adoption of this behavior was key for some lineages in establishing ecological dominance.