Spotlaw 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RELS 450 Syllabus

RELS 450 Seminar on Revisiting Religion after 9/11: Religion, Violence & Conflict (M-W 4-5:15) September 11, the war in Iraq, bombing in cities from Madrid, London to Oslo—recent years have seen an alarming global increase in religiously motivated violence, often inspired too by nationalism, colonialism, ethnic conflict, and fundamentalism. FUNDAMENTALISM Nationalism Secularism Jihad Colonialism PLURALISM War on Terror Ethnic Conflict There has perhaps never before been a time when the study of religion and violence has been so relevant to global society. RELS 450 will engage this timely and controversial topic by examining Hindu-Muslim conflicts in India, conflicts between Christian evangelicals and African animists, terrorism and the “war on terror” after 9/11, and the escalating role of religious rhetoric in American politics today. “Politics encircle us today like the coils of a snake, from which one cannot get out. In order to wrestle with this snake, I have been experimenting by introducing religion into politics.” -- M. K. Gandhi, 1920 “The cardinal doctrine of modern democratic practice is the separation of the state from religion. The idea of a religious state has no place in the mind of the modern man.”--Jawahalal Nehru, 1950 “The idea that religion and politics don’t mix was invented by the Devil to keep Christians from running their own country.” --Jerry Falwell in a sermon delivered on July 4, 1976 RELS 450 Capstone Seminar on Revisiting Religion after 9/11: Religion & Violence (MW 4-5:15 MYBK 119) Dr. Zeff Bjerken Office: 4 B Glebe, room 202 Dept. of Religious Studies Office hours: M/W 9:15-10:45; T/R: 10-11 College of Charleston E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 953-7156 Course Description Religious violence is a slippery topic, one that is sensitive, complex, potentially offensive, but of major importance. -

Allahabad, March 28 , 2017. After Finalisation of Seniority of the Officers of U.P

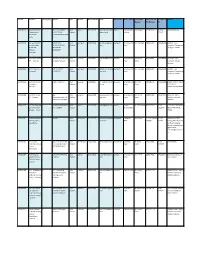

1 HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT ALLABAD CONFIDENTIAL 'A' SECTION NOTIFICATION No.C- 611 /Cf. (A)/2017, dated : Allahabad, March 28 , 2017. After finalisation of seniority of the officers of U.P. Higher Judicial Service, the earlier date for grant of Selection Grade Pay Scale mentioned in Column No.4 vacancies caused by in column No.5 to the officers are being readjusted as below mentioned in column No.6 against the vacancies caused by in column No.7 who had been granted Selection Grade Pay Scale vide Court's Notifications. No.C-212/Cf.(A)/2014 dated 03.03.2014 and No.C- 505/Cf/(A)/2015 dated 21.4.2015 in view of G.O. No.783/II-4-2010-45 (12)/91 T.C.VI dated 10.4.2010 and G.O. No.1122/II-4-45(12)91 T.C.-6 dated 18.05.2011 read with G.O. dated 04.08.2003, the High Court is pleased to grant of Selection Grade Pay Scale of Rs. 57,700-1230-58,930-1380- 67,210-1640-70,290 subject to any writ petition pending in the Hon'ble Apex Court/Hon'ble High Court. The Hon'ble Court further directed that promotions and financial benefits already given to the officers shall not be with drawn but their further prospects will be subject to seniority:- Sl.No. Sr.No. Name of officer Date of Vacancy caused by Date of Vacancy caused by vacancy vacancy earlier presently granted granted 1. 742 Dileep Singh 01/11/11 Consequent to appointment of Sri Shakti 01/08/11 Consequent to appointment of Sri Brijesh Chandra 11.10.1953 Kant in Super Time Pay Scale on Saxena in Super Time Pay Scale on 01.8.2011. -

ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Mobile No

ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Mobile No. Of Landline of Address Manager FLC Manager FLC GR09000145 Karpoori Thakur P VILL POST GANDHI Uttar Ballia 9651744234 karpoorithakur1691 Ballia Central Bank N N Kunwar 9415450332 05498- Haldi Kothi,Ballia Dhanushdhari NAGAR TELMA Pradesh @gmail.com of India 225647 Private ITC - JAMALUDDINPUR DISTT Ballia B GR09000192 Sar Sayed School P OHDARIPUR, Uttar Azamgarh 9026699883 govindazm@gmail. Azamgarh Union Bank of Shri R A Singh 9415835509 5462246390 TAMSA F.L.C.C. of Technology RAJAPURSIKRAUR, Pradesh com India Azamgarh, Collectorate, Private ITC - BEENAPARA, Azamgarh, 276001 Binapara - AZAMGARH Azamgarh GR09000314 Sant Kabir Private P Sant Kabir ITI, Salarpur, Uttar Varanasi 7376470615 [email protected] Varanasi Union Bank of Shri Nirmal 9415359661 5422370377 House No: 241G, ITC - Varanasi Rasulgarh,Varanasi Pradesh m India Kumar Ledhupur, Sarnath, Varanasi GR09000426 A.H. Private ITC - P A H ITI SIDHARI Uttar Azamgarh 9919554681 abdulhameeditc@g Azamgarh Union Bank of Shri R A Singh 9415835509 5462246390 TAMSA F.L.C.C. Azamgarh AZAMGARH Pradesh mail.com India Azamgarh, Collectorate, Azamgarh, 276001 GR09001146 Ramnath Munshi P SADAT GHAZIPUR Uttar Ghazipur 9415838111 rmiti2014@rediffm Ghazipur Union Bank of Shri B N R 9415889739 5482226630 UNION BANK OF INDIA Private Itc - Pradesh ail.com India Gupta FLC CENTER Ghazipur DADRIGHAT GHAZIPUR GR09001184 The IETE Private P 248, Uttar Varanasi 9454234449 ietevaranasi@rediff Varanasi Union Bank of Shri Nirmal 9415359661 5422370377 House No: 241G, ITI - Varanasi Maheshpur,Industrial Pradesh mail.com India Kumar Ledhupur, Sarnath, Area Post : Industrial Varanasi GR09001243 Dr. -

Quit, Non-Hindu Staff at Tirumala Temple Told

Follow us on: RNI No. APENG/2018/764698 @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer Established 1864 Published From OPINON 6 TOLLYWOOD 11 SPORTS 12 VIJAYAWADA DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL THE FEAR SAAHO MANIA GRIPS DEEPA BASKS IN RAIPUR CHANDIGARH BHUBANESWAR WITHIN TELUGU STATES KHEL RATNA GLORY RANCHI DEHRADUN HYDERABAD *Late City Vol. 1 Issue 305 VIJAYAWADA, FRIDAY AUGUST 30, 2019; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable BIG B KEEN ON WORKING IN WEB SERIES { Page 10 } www.dailypioneer.com ESL calls on AP TDP govt Guv, spouse at Quit, non-Hindu staff allotted land Hyd hospital to Balayya's VIJAYAWADA: Telangana State Governor ESL in-laws: Botsa Narasimhan and his wife PNS n VIJAYAWADA Vimala Narasimhan called at Tirumala temple told on Governor Biswa Bhusan Municipal Administration and Harichandan and his wife l Conversions are individual choices: Govt l 48 non-Hindu employees in TTD Urban Development Minister Suprava Harichandan, at a Botsa Satyanarayana on hospital in Hyderabad on PNS n TIRUPATI the opposition, especially Thursday reiterated that a Thursday. They enquired Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), company belonging to the in- about the health of Suprava The State Government has which dubbed him "anti- laws of Tollywood actor and Harichandan, who recently ordered that employees of the Hindu". Hindupur MLA Nandamuri underwent knee replacement Tirumala temple, who con- Advertisements for Balakrishna was allotted land surgery in Hyderabad. verted to non-Hindu religions Jerusalem yatra and Haj pil- in the Capital region after should quit as they can no grimage on bus tickets in the TDP came to power in 2015. more continue in their posts. -

The NEET PG Rank Wise List of Canidates Who Studied MBBS In

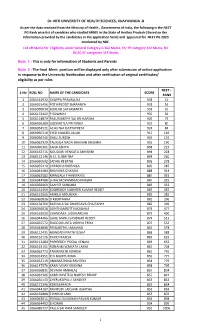

Dr. NTR UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCES, VIJAYAWADA -8 As per the data received from the Ministry of Health , Government of India, the following is the NEET PG Rank wise list of canidates who studied MBBS in the State of Andhra Pradesh ( Based on the information provided by the candidates in the application form) and appeared for NEET PG 2020 conducted by NBE. Cut off Marks for Eligibility under General Category is 366 Marks, For PH category 342 Marks, for BC,SC,ST categories 319 Marks Note 1 : This is only for information of Students and Parents Note 2 : The final Merit position will be displayed only after submission of online application in response to the University Notification and after verification of original certificates/ eligibility as per rules NEET - S.No ROLL NO NAME OF THE CANDIDATE SCORE RANK 1 2066161932 CHAPPA PRAVALLIKA 938 41 2 2066015456 POTHIREDDY SHARANYA 931 56 3 2066090034 KOULALI SAI SAMARTH 931 61 4 2066153442 P SOWMYA 930 66 5 2066114879 PASUMARTHY SAI SRI HARSHA 926 79 6 2066056289 GUDIMETLA PRIYANKA 925 80 7 2066054521 ACHUTHA DATTATREYA 924 84 8 2066090718 SYED KHALEELULLAH 910 149 9 2066056746 DALLI SURESH 909 152 10 2066062929 TALASILA NAGA BHAVANI KRISHNA 903 190 11 2066090361 SANA ASFIYA 898 223 12 2066162715 NOUDURI VENKATA ABHISHEK 898 224 13 2066112146 N S L SUSMITHA 894 260 14 2066060592 SADHU KEERTHI 892 278 15 2066055410 CHEBOLU HARSHIKA 890 287 16 2066044484 BHAVANA CHANDA 888 314 17 2066062582 MANGALA THANMAYEE 887 319 18 2066044988 SHAIK MOHAMMAD KHASIM 887 325 19 2066056960 SAAHITI SUNKARA 885 -

Directory of Officers - Uttar Pradesh (East) Telephone Directory of Income Tax Offices U

DIRECTORY OF OFFICERS - UTTAR PRADESH (EAST) TELEPHONE DIRECTORY OF INCOME TAX OFFICES U. P. (EAST) , LUCKNOW CHIEF COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX, LUCKNOW Name S.No. DESIGNATION ADDRESS (O) PHONE (O) FAX (O) MOBILE (Shri/Smt./Ms.) AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 - ASHOK 1 ARUN KUMAR SINGH CCIT (CCA) 0522-2233201 0522-2233210 8005445292 MARG, LUCKNOW ADDL. CIT (HQ), O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 8005445319 2 TAJINDER PAL SINGH 0522-2233202 0522-2233209 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW 0872080468 ADDL. CIT (Vig.) O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 8005445319 3 TAJINDER PAL SINGH 0522-2233203 0522-2233213 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW 0872080468 DY. CIT (HQ) Admn., AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 4 O. N. PATHAK 0522-2233204 0522-2233204 8005446100 O/o CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW DY. CIT (Judl.), O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 5 RANJAN SRIVASTAVA 0522-2233294 0522-2233294 8005445123 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW DY. CIT (Vig.), O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 6 SARAS KUMAR 0522-2233207 0522-2233207 8005445054 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW ACIT (Tech.), O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 7 G. D. SINGH 0522-2233208 0522-2233208 8005445001 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW ITO (HQ) Admn., O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 8 VIVEK NAGRATH 0522-2233206 0522-2233206 8005445321 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW ITO (HQ) / PR, O/o AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 9 PRAJESH SRIVASTAVA 0522-2233205 0522-2233205 8005445350 CCIT, LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW MSTU, PRAGYA BHAWAN, DTRTI, 10 ATUL SONKAR ITO (MSTU) 0522-2720344 0522-2720344 8005445231 GOMTI NAGAR, LUCKNOW. AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 11 JYOTI SHARMA ITO (OSD) - - 9967033678 MARG, LUCKNOW AO / DDO, O/o CCIT, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 12 ROOP SAXENA 0522-2233241 0522-2233241 8005445008 LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW AO O/o CCIT, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 13 MUJEEB ASHRAF 0522-2233239 - 8005445011 LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW PS, O/o CCIT, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 14 ANITA GUPTA 0522-2233201 0522-2233210 8005445010 LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW PS, O/o CCIT, AAYAKAR BHAWAN, 5 -ASHOK 15 MANJU AGARWAL 0522-2233203 0522-2233213 8005445287 LUCKINOW MARG, LUCKNOW AD (OL), O/o CCIT, RADHA KUNTI BHAWAN, 16 S. -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

STUDENT MARKS DETAILS of 2019- ME- I Year- II Sem- Regular

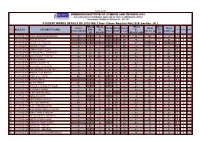

6236-6305 STUDENT MARKS DETAILS OF 2019- ME- I Year- II Sem- Regular- Nov,2020- Section : ALL 7HC08 7HC01 7HC61 7B292 7HC03 7FC01 7BC01 7HC63 7FC61 7BC61 S.No ROLLNO STUDENT NAME EM- E- E- TS- Credits Backlogs SGPA CHEMISTRY PSUC WMP CLAB PSUCLAB WMPLAB III RL&W RL&WLAB III 1 18311A0377 GHALI VENKATA BHARADWAJ B F B F C B+ O B+ A+ A 12.5 2 4.46 2 18311A0396 PALLEM SUJEETH F F C F F B+ O C A+ A+ 7.5 4 2.85 3 18311A03D5 DASARI SAI CHANDRA F F F F F B+ A+ F B F 3.5 7 1.31 4 18311A03F4 NAMSANI NITHIN B C A F C B+ A C A+ A 16.5 1 5.33 5 19311A0301 EMMADI VIVEK REDDY A O A+ A+ A+ O O O O O 19.5 0 9.33 6 19311A0302 THANGADIPELLI SAI PRANITH A+ A+ B+ A B+ O A+ O A+ A+ 19.5 0 8.79 7 19311A0303 MANVITH REDDY PALVAI A+ B+ B+ C B O A+ O O A+ 19.5 0 7.92 8 19311A0304 SRIRAM ROHAN A+ B A+ B B+ A+ A+ A+ A+ O 19.5 0 7.90 9 19311A0305 PUNDRU GOWTHAM A A A B+ A+ A+ A+ A O A+ 19.5 0 8.21 10 19311A0306 MADUGULA SAI KUMAR A B A A A A+ A A A+ A+ 19.5 0 7.79 11 19311A0307 PILLI SREENA LALITHA DEVI A B+ A+ B B O A+ O A+ A+ 19.5 0 7.92 12 19311A0308 TANDYALA SAI RISHVIK O A+ A B+ B+ A+ O O O O 19.5 0 9.00 13 19311A0309 RAMA SAI CHARAN B+ F B+ F B A B+ A A A+ 12.5 2 4.79 14 19311A0310 MERGU ROHITH F F A F B A+ B+ B+ A A 8.5 3 3.33 15 19311A0311 JOLAM VAMSHI B+ F B+ F B+ O B+ B+ B+ A 12.5 2 4.79 16 19311A0312 BATHINI VIJAYENDHAR GOUD B F A F B A+ A+ A+ A A+ 12.5 2 4.90 17 19311A0313 R KRISHNA VAMSHI A B+ O A A A+ A+ O O A+ 19.5 0 8.36 18 19311A0314 M SAI KRISHNA GOUD B+ C A+ B F A+ A B+ A O 18.5 1 6.67 19 19311A0315 BOMMA MANISH A F B+ F B A+ A B+ A A+ 12.5 2 5.05 -

The Strange Existence of Ram Charan

The strange existence of Ram Charan What he does is hard to describe. But the most powerful CEOs love it enough to keep him on the road 24/7 and make him the most influential consultant alive. Fortune's David Whitford reports. (Fortune Magazine) -- The Al Manzil Hotel in Dubai has been open for business all of 18 days on the Saturday night in January that I show up with Ram Charan. The lobby is strangely quiet; there doesn't seem to be anybody else staying here. The surrounding neighborhood is called Old Town, but in fact it's a construction site from which are rising what will one day be the world's tallest skyscraper and the world's biggest mall. Soulless and kind of creepy, I'm thinking, but Charan's thoughts are elsewhere. Already he has claimed an overstuffed chair in the center of the lobby and is talking on the phone. After 12 hours of isolation on the flight from J.F.K., Charan is back in business, deep in private conversation with a client in New York City. He looks tired, and no wonder. He began his day with a 4 A.M. Friday wake-up call in Richmond (he did a Squawk Box live remote on CNBC), and he has a head cold. But he is in no hurry to go to bed. Charan doesn't care what time it is. He doesn't care what day of the week it is. And the last thing he cares about is where he is. As long as Charan is with a client - or can get one on the phone - he's home. -

STCC-Founding Principles

Sanatan Temple and Cultural Center Thoughts and Emotions Behind its Creation and Operation All the cosmic elements from fire to water that create and sustain life are represented in a Hindu temple. The temple atmosphere is filled with the sounds of temple bells and sweet smells of incense and chanting of prayers for peace and prosperity for all. ॐ सर्वे भर्वꅍतु सखु िनः सर्वे सꅍतु ननरामयाः । सर्वे भद्राखि प�यꅍत ु मा कश्�िद्ःु िभा嵍भर्वते ् । ॐ शाश्ꅍतः शाश्ꅍतः शाश्ꅍतः ॥ Om Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah Sarve Santu Niraamayaah | Sarve Bhadraanni Pashyantu Maa Kashcid-Duhkha-Bhaag-Bhavet | Om Shaantih || Meaning: 1: Om, May All be Happy, 2: May All be Free from Illness. 3: May All See what is Auspicious, 4: May no one Suffer. 5: Om Peace, Peace, Peace. The temple provides a common place for the community to strengthen emotional connection (Bhava) with the supreme Sagun Brahm (Bhagwan). Visiting the Temple for service, prayer or darshan (properly seeing God with devotion and concentration) helps the devotee to make that connection, Bhav-Sadhana. Bhav se Bhagwan Prapti: To make it possible for people from all parts from India to achieve that emotional connection the community worked together whole heartedly and elected the Vigrahas to be installed in the Temple. The Philosophy Behind the Design of the Temple Selection of Temple Location Even though people of Indian origin and Hindu faith started settling in the Charleston area in the 1960s the community did not reach a critical mass until the first decade of the 21st century. -

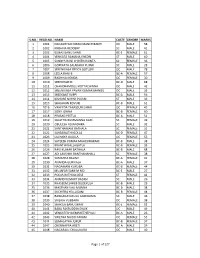

S.No. Regd.No. Name Caste Gender Marks 1 1001

S.NO. REGD.NO. NAME CASTE GENDER MARKS 1 1001 NAGASHYAM KIRAN MANCHIKANTI OC MALE 58 2 1002 KRISHNA REDDERY SC MALE 41 3 1003 ELMAS BANU SHAIK BC-E FEMALE 61 4 1004 VENKATA RAMANA KHEDRI ST MALE 60 5 1005 SANDYA RANI CHINTHAKUNTA SC FEMALE 36 6 1006 GOPINATH SALAKARU PUJARI SC MALE 28 7 1007 SREENIVASA REDDY GOTLURI OC MALE 78 8 1008 LEELA RANI B BC-A FEMALE 57 9 1009 RADHIKA KONDA OC FEMALE 30 10 1010 SREEDHAR M BC-D MALE 68 11 1011 CHANDRAMOULI KOTTACHINNA OC MALE 42 12 1012 SREENIVASA PAVAN KUMAR MANGU OC MALE 35 13 1013 SREEKANT SUPPI BC-A MALE 56 14 1014 KISHORE NAYAK PUJARI ST MALE 39 15 1015 SHAJAHAN KOVURI BC-B MALE 61 16 1016 VAHEEDA TABASSUM SHAIK OC FEMALE 45 17 1017 SONY JONNA BC-B FEMALE 60 18 1018 PRASAD PEETLA BC-A MALE 51 19 1019 SUJATHA BUMMANNA GARI SC FEMALE 49 20 1020 OBULESH ADIANDHRA SC MALE 32 21 1021 SANTHAMANI BATHALA SC FEMALE 31 22 1022 SARASWATHI GOLLA BC-D FEMALE 47 23 1023 LAVANYA GAJULA OC FEMALE 55 24 1024 SATEESH KUMAR MAHESWARAM BC-B MALE 38 25 1025 KRANTHI NALLAGATLA BC-B FEMALE 33 26 1026 RAVI KUMAR BATHALA BC-B MALE 68 27 1027 ADI LAKSHMI BANTHANAHALL SC FEMALE 38 28 1028 SAMATHA BALIMI BC-A FEMALE 41 29 1030 ANANDA GURIKALA BC-A MALE 37 30 1031 NAGAMANI KURUBA BC-B FEMALE 44 31 1032 MUJAFAR SAMI M MD BC-E MALE 27 32 1033 POOJA RATHOD DESE ST FEMALE 42 33 1034 ANAND KUMART BADIGI SC MALE 26 34 1035 KHASEEM SAHEB DUDEKULA BC-B MALE 29 35 1036 MASTHAN VALI MUNNA BC-B MALE 38 36 1037 SUCHITRA YELLUGANI BC-B FEMALE 44 37 1038 RANGANAYAKULU GUDIDAMA SC MALE 46 38 1039 SAILAJA VUBBARA OC FEMALE 38 39 1040 SHAKILA BANU SHAIK BC-E FEMALE 52 40 1041 BABA FAKRUDDIN SHAIK OC MALE 49 41 1042 VENKATESH DEMAKETHEPALLI BC-A MALE 26 42 1043 SWETHA NAIDU PAKAM OC FEMALE 55 43 1044 SUMALATHA JUKUR BC-B FEMALE 37 44 1047 CHENNAPPA ARETI BC-A MALE 29 45 1048 NAGARAJU CHALUKURU OC MALE 40 Page 1 of 127 S.NO. -

AGRA Code NAME of the COLLEGE Code NAME of the EXAMINATION CENRE 0236 236-GOVT PG COLLEGE FATEHABAD AGRA 0236 236-GOVT PG COLLEG

AGRA Code NAME OF THE COLLEGE Code NAME OF THE EXAMINATION CENRE 0236 236-GOVT PG COLLEGE FATEHABAD AGRA 0236 236-GOVT PG COLLEGE FATEHABAD AGRA 0539 539-BDM GIRLS COLLGE FATEHABAD AGRA 0539 539-BDM GIRLS COLLGE FATEHABAD AGRA 0494 494-JANGJIT SINGH DEGREE COLLEGE 0449 449-RAJENDRA SINGH COLLEGE 0179 179-DAV COLLEGE KUNDOL 0494 494-JANGJIT SINGH DEGREE COLLEGE 0731 731-JSSM DEGREE COLLEGE 0179 179-DAV COLLEGE KUNDOL 0811 811-SSR COLLEGE 0179 179-DAV COLLEGE KUNDOL 0581 581-ILAICHI DEVI DEGREE COLLEGE 0147 147-KRISHNA COLLEGE 0545 545-RADHEY JAMUNA GIRLS COLLEGE 0545 545-RADHEY JAMUNA GIRLS COLLEGE 0147 147-KRISHNA COLLEGE 0494 494-JANGJIT SINGH COLLEGE 0582 582-DAUJI MAHARADA DEGREE COLLEGE 0783 783-SHARWOOD COLLEGE 0783 783-SHARWOOD COLLEGE 0490 490-RAM CHARAN COLLEGE 0088 88-SBS GIRLS COLLEGE 0088 88-SBS GIRLS COLLEGE 0588 588-SMT. KD DEGREE COLLEGE 0179 179-DAV COLLEGE KUNDOL 0490 490-RAM CHARAN DEGREE COLLEGE 0582 582-DAU JI MAHARAJ COLLEGE 0845 845-THAKUR OP SINGH COLLEGE 0781 781-DEVI SINGH COLLEGE 0061 61-Pt. Shri JAGANNATH PRASAD COLLEGE, Agra 0845 845-THAKUR O P SINGH COLLEGE 0449 449-RAJENDRA SINGH DEGREE COLLEGE 0059 59-BANKEY BIHARI COLLEGE 0220 220-LAXMI DEVI GIRLS DEGREE COLLEGE 0220 220-LAXMI DEVI GIRLS DEGREE COLLEGE 0285 285-NATHIYA DEVI DEGREE COLLEGE 0308 308-S S COLLEGE 0308 308-S S DEGREE COLLEGE 0476 476- ND College of Sc. & Tech., Shyamo Mod, Agra 0059 59-BANKEY BIHARI DEGREE COLLEGE 0845 845-THAKUR O P SINGH COLLEGE 0988 988-BVM COLLEGE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 0494 494-JANGJIT SINGH COLLEGE 0476 476- ND College of Sc.