Painted Turtle Ecology in a Freshwater Tidal Marsh: Concluding Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competing Generic Concepts for Blanding's, Pacific and European

Zootaxa 2791: 41–53 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Competing generic concepts for Blanding’s, Pacific and European pond turtles (Emydoidea, Actinemys and Emys)—Which is best? UWE FRITZ1,3, CHRISTIAN SCHMIDT1 & CARL H. ERNST2 1Museum of Zoology, Senckenberg Dresden, A. B. Meyer Building, D-01109 Dresden, Germany 2Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, MRC 162, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, USA 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We review competing taxonomic classifications and hypotheses for the phylogeny of emydine turtles. The formerly rec- ognized genus Clemmys sensu lato clearly is paraphyletic. Two of its former species, now Glyptemys insculpta and G. muhlenbergii, constitute a well-supported basal clade within the Emydinae. However, the phylogenetic position of the oth- er two species traditionally placed in Clemmys remains controversial. Mitochondrial data suggest a clade embracing Actinemys (formerly Clemmys) marmorata, Emydoidea and Emys and as its sister either another clade (Clemmys guttata + Terrapene) or Terrapene alone. In contrast, nuclear genomic data yield conflicting results, depending on which genes are used. Either Clemmys guttata is revealed as sister to ((Emydoidea + Emys) + Actinemys) + Terrapene or Clemmys gut- tata is sister to Actinemys marmorata and these two species together are the sister group of (Emydoidea + Emys); Terra- pene appears then as sister to (Actinemys marmorata + Clemmys guttata) + (Emydoidea + Emys). The contradictory branching patterns depending from the selected loci are suggestive of lineage sorting problems. Ignoring the unclear phy- logenetic position of Actinemys marmorata, one recently proposed classification scheme placed Actinemys marmorata, Emydoidea blandingii, Emys orbicularis, and Emys trinacris in one genus (Emys), while another classification scheme treats Actinemys, Emydoidea, and Emys as distinct genera. -

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys Picta)

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta) Class: Reptilia Order: Testudines Family: Emydidae Characteristics: The most widespread native turtle of North America. It lives in slow-moving fresh waters, from southern Canada to Louisiana and northern Mexico, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The adult painted turtle female is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long; the male is smaller. The turtle's top shell is dark and smooth, without a ridge. Its skin is olive to black with red, orange, or yellow stripes on its extremities. The subspecies can be distinguished by their shells: the eastern has straight-aligned top shell segments; the midland has a large gray mark on the bottom shell; the southern has a red line on the top shell; the western has a red pattern on the bottom shell (Washington Nature Mapping Program). Behavior: Although they are frequently consumed as eggs or hatchlings by rodents, canines, and snakes, the adult turtles' hard shells protect them from most predators. Reliant on warmth from its surroundings, the painted turtle is active only during the day when it basks for hours on logs or rocks. During winter, the turtle hibernates, usually in the mud at the bottom of water bodies. Reproduction: The turtles mate in spring and autumn. Females dig nests on land and lay eggs between late spring and mid- summer. Hatched turtles grow until sexual maturity: 2–9 years for males, 6–16 for females. Diet: Wild: aquatic vegetation, algae, and small water creatures including insects, crustaceans, and fish Zoo: Algae, duck food Conservation: While habitat loss and road killings have reduced the turtle's population, its ability to live in human-disturbed settings has helped it remain the most abundant turtle in North America. -

Box Turtles July 2017

The HERP Project, Herpetology Education in Rural Places and Spaces In Awe of Nature: Treasuring Terrestrial Turtles By Ann Berry Somers, Catherine Matthews, and Lacey Huffling The Herp Project is supported by the National Science Foundation, Grant No. DRL-1114558. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Treasuring Terrestrial Turtles Before starting a project like the one described in this curriculum, contact your state wildlife resources commission or state division of fish and game to see what permits you need to work with box turtles. I. Project Description This curriculum was developed by The HERP (Herpetology Education in Rural Places and Spaces) Project to introduce participants to the wonders of nature and science through the study of box turtles (Terrapene spp.). The curriculum was developed over several years of working with high school students in our Herpetological Research Experience (HRE) residential program. Feel free to modify this curriculum as needed. In our program, participants are introduced to turtle biology as well as to The Box Turtle Connection (BTC), our long-term mark/recapture box turtle study in North Carolina. The BTC is designed to follow temporal trends in population size and structure (sex, age class) as well as the health and condition of individual box turtles from numerous sites across North Carolina. The data collected are important to help scientists determine if box turtles need special conservation measures to maintain their populations and thrive in their natural habitat. Our box turtle studies are enhanced by use of Boykin Spaniel dogs to locate and retrieve box turtles and use of radio tracking to determine activity ranges for male and female box turtles. -

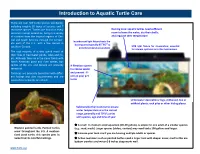

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Steven P. Krichbaum May 2018 © 2018 Steven P. Krichbaum. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians by STEVEN P. KRICHBAUM has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Willem Roosenburg Professor of Biological Sciences Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract KRICHBAUM, STEVEN P., Ph.D., May 2018, Biological Sciences Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians Director of Dissertation: Willem Roosenburg My study presents information on summer use of terrestrial habitat by IUCN “endangered” North American Wood Turtles (Glyptemys insculpta), sampled over four years at two forested montane sites on the southern periphery of the species’ range in the central Appalachians of Virginia (VA) and West Virginia (WV) USA. The two sites differ in topography, stream size, elevation, and forest composition and structure. I obtained location points for individual turtles during the summer, the period of their most extensive terrestrial roaming. Structural, compositional, and topographical habitat features were measured, counted, or characterized on the ground (e.g., number of canopy trees and identification of herbaceous taxa present) at Wood Turtle locations as well as at paired random points located 23-300m away from each particular turtle location. -

Conservation Biology of the European Pond Turtle Emys Orbicularis (L) in Italy 219-228 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Stapfia Jahr/Year: 2000 Band/Volume: 0069 Autor(en)/Author(s): Zuffi Marco A. L. Artikel/Article: Conservation biology of the European pond turtle Emys orbicularis (L) in Italy 219-228 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Conservation biology of the European pond turtle Emys orbicularis (L) in Italy M.A.L. ZUFFI Abstract Key words The updated situation and knowledge Emys orbicularis, distribution, ecology, of the biology, ecology, behaviour and pro- conservation, Italy, tection of the European pond turtle, Emys orbicularis (L.) in Italy is presented and discussed in the light of conservation bio- logical issues. Stapfia 69, zugleich Kataloge des OÖ. Landesmuseums, Neue Folge Nr. 149 (2000), 219-228 219 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Introduction In this last decade, a "Big Bang" of interest in Italian populations of E. orbiculans enabled Populations of Emys orbicularis in Italy are to build up a consistent data set. Information distributed mainly in coastal areas and inter- on biometry (Zum & GARIBOLDI 1995a, b), nal plains. Most regions of Italy have been systematics (FRITZ & OBST 1995; FRITZ 1998), mapped, but in some cases the information is population structure (KELLER et al. 1998; KEL- incomplete (Fig. 1, Societas Herpetologica LER 1999), space usage (LEBBOROM & CHELA - Italica 1996). An uncomplete knowledge of ZZI 1991), reproductive biology (ZUFFI & habitat use leads to a biased view on the ODETTI 1998; ZUFFI et al. 1999; KELLER 1999), and thermal ecology (Dl TRAM & ZUFFI 1997), have become available. -

EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles

REPTILIA: TESTUDINES: EMYDIDAE P Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Pseudemysj7oridana: Baur, 1893:223 (part). Pseudemys texana: Brimley, 1907:77 (part). Seidel, M.E. and M.J. Dreslik. 1996. Pseudemys concinna. Chrysemysfloridana: Di tmars, 1907:37 (part). Chrysemys texana: Hurter and Strecker, 1909:21 (part). Pseudemys concinna (LeConte) Pseudemys vioscana Brimley, 1928:66. Type-locality, "Lake River Cooter Des Allemands [St. John the Baptist Parrish], La." Holo- type, National Museum of Natural History (USNM) 79632, Testudo concinna Le Conte, 1830: 106. Type-locality, "... rivers dry adult male collected April 1927 by Percy Viosca Jr. of Georgia and Carolina, where the beds are rocky," not (examined by authors). "below Augusta on the Savannah, or Columbia on the Pseudemys elonae Brimley, 1928:67. Type-locality, "... pond Congaree," restricted to "vicinity of Columbia, South Caro- in Guilford County, North Carolina, not far from Elon lina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, see College, in the Cape Fear drainage ..." Holotype, USNM Comment. 79631, dry adult male collected October 1927 by D.W. Tesrudofloridana Le Conte, 1830: 100 (part). Type-locality, "... Rumbold and F.J. Hall (examined by authors). St. John's river of East Florida ..." Holotype, undesignated, see Comment. Emys (Tesrudo) concinna: Bonaparte, 1831 :355. Terrapene concinna: Bonaparte, 183 1 :370. Emys annulifera Gray, 183 1:32. Qpe-locality, not given, des- ignated as "Columbia [Richland County], South Carolina" by Schmidt (1953: 101). Holotype, undesignated, but Boulenger (1889:84) listed the probable type as a young preserved specimen in the British Museum of Natural His- tory (BMNH) from "North America." Clemmys concinna: Fitzinger, 1835: 124. -

In AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): Species in Red = Depleted to the Point They May Warrant Federal Endangered Species Act Listing

Southern and Midwestern Turtle Species Affected by Commercial Harvest (in AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): species in red = depleted to the point they may warrant federal Endangered Species Act listing Common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) – AR, GA, IA, KY, MO, OH, OK, SC, TX Florida common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina osceola) - FL Southern painted turtle (Chrysemys dorsalis) – AR Western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) – IA, MO, OH, OK Spotted turtle (Clemmys gutatta) - FL, GA, OH Florida chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia chrysea) – FL Western chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia miaria) – AR, FL, GA, KY, MO, OK, TN, TX Barbour’s map turtle (Graptemys barbouri) - FL, GA Cagle’s map turtle (Graptemys caglei) - TX Escambia map turtle (Graptemys ernsti) – FL Common map turtle (Graptemys geographica) – AR, GA, OH, OK Ouachita map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis) – AR, GA, OH, OK, TX Sabine map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis sabinensis) – TX False map turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) – MO, OK, TX Mississippi map turtle (Graptemys pseuogeographica kohnii) – AR, TX Alabama map turtle (Graptemys pulchra) – GA Texas map turtle (Graptemys versa) - TX Striped mud turtle (Kinosternon baurii) – FL, GA, SC Yellow mud turtle (Kinosternon flavescens) – OK, TX Common mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum) – AR, FL, GA, OK, TX Alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) – AR, FL, GA, LA, MO, TX Diamond-back terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) – FL, GA, LA, SC, TX River cooter (Pseudemys concinna) – AR, FL, -

Eastern Painted Turtle Chrysemys Picta Picta Description Painted Turtles Are Commonly Found Around Quiet Bodies of Water

WILDLIFE IN CONNECTICUT WILDLIFE FACT SHEET Eastern Painted Turtle Chrysemys picta picta Description Painted turtles are commonly found around quiet bodies of water. These brightly colored turtles gain their name J. FUSCO © PAUL from colorful markings along the head, neck, and shell. They often can be observed basking on logs and rocks around a body of water and will quickly scoot into water if threatened or disturbed. The medium-sized painted turtle can be distinguished by its dark shell, which has olive lines running across the carapace (upper shell), dividing the large scutes (scales). The margin of both the carapace and plastron (bottom shell) have black and red markings. The head, neck, and limbs have yellow stripes. The plastron is typically yellow, but may be stained a rust/red color. Males can be distinguished from females by their long front claws, long tail, and smaller size. The carapace of an adult usually measures from 4.5 to 6 inches in length. Range The painted turtle is the most widely distributed North basking on rocks and logs, even on top of one another. American turtle, and the only one to range across the Opportunistic, painted turtles can be found in brackish entire continent. This species ranges from coast to tidal waters and salt marshes. Much of their time is spent coast through the northern United States and southern concealed in submerged vegetation. The turtles spend Canada, south to the Gulf of Mexico from Louisiana to the winter hibernating in mud or decayed vegetation southwestern Alabama. on pond bottoms, emerging earlier than other turtles, The painted turtle is Connecticut's most numerous turtle typically in March. -

Assessment for the Western Pond Turtle Final Report

Assessment for the Western Pond Turtle Final Report Client: United States Fish and Wildlife Service Primary Advisor: Brad Shaffer Secondary Advisor: Peter Scott Team Members: Zachary Devereux Hogan Fenster Stephanie Manzo Thomas Morgan Griffin Nicholson Delacey Rodriguez Bianca Sanchez University of California, Los Angeles Executive Summary Western Pond Turtle Report June 2019 The western pond turtle (WPT), recently separated into two species, is a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act. To assess the current status of both species, we conducted a risk assessment and analysis of historical, current, and future conditions. Background This assessment for the WPT compiles the best available literature, scientific information, museum data, and population viability analyses to characterize the biological status of the two species: Emys (Actinemys) pallida and Emys (Actinemys) marmorata. The goal of this assessment is to inform the listing decision for the two species under the federal Endangered Species Act, and to act as a source of information for future conservation efforts. Species Biology and Needs The WPT occurs in a variety of semi-aquatic habitats ranging from lakes, rivers, and streams to man-made channels, agricultural ponds, and sewage treatment ponds. Emys pallida can be found from northern Baja California, Mexico to the southern San Francisco Bay area along the coast and inland deserts. It can be found along the Southern Coast Ranges and the western parts of the San Joaquin Valley. Emys marmorata can be found from the San Francisco bay area north to Washington state and south along the eastern side of the San Joaquin Valley. The WPT is a medium sized pond turtle that has a maximum life span of about 45 years (Holland 1994, p. -

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys Picta Belli) Overview

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta belli) Overview Predicted Impacts Habitat Change 2030 26 to 68 % Loss 2060 48 to 82 % Loss 2090 96 to 100 % Loss Adaptive capacity Moderately Low Fire Response Mixed Status: Chrysemys picta has four subspecies, of which only C. p. belli is found within New Mexico. Collectively, C. picta are considered “Demonstrably Secure” in the Natural Heritage global rank but more locally, C. p. belli is considered a species of greatest conservation need in New Mexico and critically imperiled in Arizona by State Heritage Programs (NMDGF 2006). Range and Habitat: The western painted turtle is found throughout the western U.S. though its range is limited to riparian systems in warmer areas like the Southwest (Figure 1). Chrysemys picta belli is an aquatic species that is found in slow-moving or still water bodies. This species has been found on the margins of lakes and river pools, streams, ditches and cattle tanks. They can be present in ponds as much as a mile from a river and are typically not found in the river itself, but in water bodies associated with rivers. Nests are dug in a variety of soils (with a depth of at least 9 cm) in a sunny area. Figure 1. Range of Crysemys picta belli (in blue) Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta belli) Climate Impacts and Adaptive Capacity Adaptive Capacity Score = 0.84 (Moderately low) Though C. p. belli is likely to be sensitive to a number of future changes, it scored neutral for many traits (Table 1). The western painted turtle is closely associated with wet habitats in the southwest, with few specific requirements outside of the presence of water.