Chan Buddhism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

The Development of Prajna in Buddhism from Early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita System: with Special Reference to the Sarvastivada Tradition

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition Qing, Fa Qing, F. (2001). The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/15801 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40730 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Dcvelopmcn~of PrajfiO in Buddhism From Early Buddhism lo the Praj~iBpU'ranmirOSystem: With Special Reference to the Sarv&tivada Tradition Fa Qing A DISSERTATION SUBMIWED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY. ALBERTA MARCI-I. 2001 0 Fa Qing 2001 1,+ 1 14~~a",lllbraly Bibliolheque nationale du Canada Ac uisitions and Acquisitions el ~ibqio~raphiiSetvices services bibliogmphiques The author has granted anon- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant a la National Library of Canada to Eiblioth&quenationale du Canada de reproduce, loao, distribute or sell reproduire, priter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’S Mentality

International Conference of Electrical, Automation and Mechanical Engineering (EAME 2015) The Evolvement of Buddhism in Southern Dynasty and Its Influence on Literati’s Mentality X.H. Li School of literature and Journalism Shandong University Jinan China Abstract—In order to study the influence of Buddhism, most of A. Sukhavati: Maitreya and MiTuo the temples and document in china were investigated. The results Hui Yuan and Daolin Zhi also have faith in Sukhavati. indicated that Buddhism developed rapidly in Southern dynasty. Sukhavati is the world where Buddha live. Since there are Along with the translation of Buddhist scriptures, there were lots many Buddha, there are also kinds of Sukhavati. In Southern of theories about Buddhism at that time. The most popular Dynasty the most prevalent is maitreya pure land and MiTuo Buddhist theories were Prajna, Sukhavati and Nirvana. All those theories have important influence on Nan dynasty’s literati, pure land. especially on their mentality. They were quite different from The advocacy of maitreya pure land is Daolin Zhi while literati of former dynasties: their attitude toward death, work Hui Yuan is the supporter of MiTuo pure land. Hui Yuan’s and nature are more broad-minded. All those factors are MiTuo pure land wins for its simple practice and beautiful displayed in their poems. story. According to < Amitabha Sutra>, Sukhavati is a perfect world with wonderful flowers and music, decorated by all Keyword-the evolvement of buddhism; southern dynasty; kinds of jewelry. And it is so easy for every one to enter this literati’s mentality paradise only by chanting Amitabha’s name for seven days[2] . -

Zen Is a Form of Buddhism That Developed First in China Around the Sixth Century CE and Then Spread from China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan

Zen Zen is a form of Buddhism that developed first in China around the sixth century CE and then spread from China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan. The term Zen is just the Japanese way of saying the Chinese word Chan ( 禪 ), which is the Chinese translation of the Sanskrit word Dhyāna (Jhāna in Pali), which means "meditation." In the image above one sees on the left the character 禪 in Japanese calligraphy and on the right an ensō, or Zen circle. In Japan the drawing of such a circle is considered a high art, the expression of a moment of enlightenment by the Zen master calligrapher. The tradition known as Chan Buddhism in China, and Zen Buddhism in Japan, brings together Mahāyāna Buddhism and Daoism. This confluence of Buddhism and Daoism in Zen is most obvious in the Chinese script on the left which reads: "The heart-mind (xin 心) is the buddha (佛), the buddha (佛) is the path (dao 道), the path (dao 道) is meditation (chan 禪)." The line is from a text called the Bloodstream Sermon attributed to the legendary Bodhidharma. An Indian meditation master, Bodhidharma had come to China around 520 CE and in time would come to be regarded as the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism. In Bodhidharma’s Bloodstream Introduction to Asian Philosophy Zen Buddhism Sermon (in the Chan Buddhism online selections) it is evident that Bodhidharma had absorbed something of Daoism after he came to China. The Mahāyāna Buddhist teachings that are most evident in Bodhidharma’s text are the teachings of emptiness (Śūnyatā) from the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras as well as the notion of the buddha-nature (dharmakāya) that is part of the Mahāyāna teaching of the three bodies (trikāya) of the Buddha. -

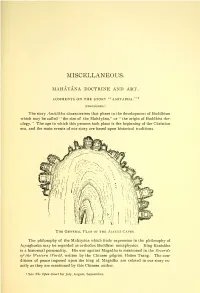

The Mahayana Doctrine and Art. Comments on the Story of Amitabha

MISCEIvIvANEOUS. MAHAYANA DOCTRINE AND ART. COMMENTS ON THE STORY "AMITABHA."^ (concluded.) The story Amitabha characterises that phase in the development of Buddhism which may be called " the rise of the Mahayana," or " the origin of Buddhist the- ology." The age in which this process took place is the beginning of the Christian era, and the main events of our story are based upon historical traditions. The General Plan of the Ajant.v Caves. The philosophy of the Mahayana which finds expression in the philosophy of Acvaghosha may be regarded as orthodox Buddhist metaphysics. King Kanishka is a historical personality. His war against Magadha is mentioned in the Records of the Western IVorld, written by the Chinese pilgrim Hsiien Tsang. The con- ditions of peace imposed upon the king of Magadha are related in our story ex- actly as they are mentioned by this Chinese author. 1 See The Open Court for July, August, September. 622 THE OPEN COURT. The monastic life described in the first, second, and fifth chapters of the story Amitdbha is a faithful portrayal of the historical conditions of the age. The ad- mission and ordination of monks (in Pali called Pabbajja and Upasampada) and the confession ceremony (in Pfili called Uposatha) are based upon accounts of the MahSvagga, the former in the first, the latter in the second, Khandaka (cf. Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIII.). A Mother Leading Her Child to Buddha. (Ajanta caves.) Kevaddha's humorous story of Brahma (as told in The Open Cozirt, No. 554. pp. 423-427) is an abbreviated account of an ancient Pali text. -

The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra (2Nd Edition)

TheThe PrajnaPrajna ParamitaParamita HeartHeart SutraSutra Translated by Tripitaka Master Hsuan Tsang Commentary by Grand Master T'an Hsu English Translation by Ven. Master Lok To Second Edition 2000 HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra Translated from Sanskrit into Chinese By Tripitaka Master Hsuan Tsang Commentary By Grand Master T’an Hsu Translated Into English By Venerable Dharma Master Lok To Edited by K’un Li, Shih and Dr. Frank G. French Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada New York – San Francisco – Toronto 2000 First published 1995 Second Edition 2000 Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada Dharma Master Lok To, Director 2611 Davidson Ave. Bronx, New York 10468 (USA) Tel. (718) 584-0621 2 Other Works by the Committee: 1. The Buddhist Liturgy 2. The Sutra of Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha’s Fundamental Vows 3. The Dharma of Mind Transmission 4. The Practice of Bodhisattva Dharma 5. An Exhortation to Be Alert to the Dharma 6. A Composition Urging the Generation of the Bodhi Mind 7. Practice and Attain Sudden Enlightenment 8. Pure Land Buddhism: Dialogues with Ancient Masters 9. Pure-Land Zen, Zen Pure-Land 10. Pure Land of the Patriarchs 11. Horizontal Escape: Pure Land Buddhism in Theory & Practice. 12. Mind Transmission Seals 13. The Prajna Paramita Heart Sutra 14. Pure Land, Pure Mind 15. Bouddhisme, Sagesse et Foi 16. Entering the Tao of Sudden Enlightenment 17. The Direct Approach to Buddhadharma 18. -

Diamond Sutra) 『菩薩於法,應無所住,行於布施

Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas Sponsored By Pure Land Center & Buddhist LiBrary 1120 E. Ogden Avenue, Suite 108 Naperville, IL 60563 http://www.amitabhalibrary.org Tel: (630) 428-9941; Fax: (630) 428-9961 Presenter: Bert T. Tan / Consultant: Venerable Wu Ling Slide 1 Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas q A quick review Ø Topic One : The Basics èBuddhism is an education, not a religion or a philosophy n It teaches us how to recover our wisdom and regain our Buddha nature n It teaches us how to solve our proBlems through wisdom – an art of living èThe Law of Causality governs everything in the universe èAll sentient Beings possess the same Buddha nature n Our Buddha nature is temporarily lost due to delusion n Our lost Buddha nature can be recovered only via cultivation èKarma refers to an action and its retriBution under the Law of Causality n Good and bad karmas do not offset each other – prevailing ones occur first n Karmas, good or Bad, accumulate over time and do not disappear n When many Bad karmic retriButions come together, they form disasters èCultivation means to stop planting Bad seeds and nurturing Bad conditions, and to, instead, plant good seeds and nurture good conditions Last updated Nov. 2016 Presenter: Bert T. Tan / Consultant: Venerable Wu Ling Slide 2 Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas q A quick review Ø Topic Two : The Three Refuges and the Four Reliance -

A Geographic History of Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism: the Decline of the Yunmen Lineage

decline of the yunmen lineage Asia Major (2019) 3d ser. Vol. 32.1: 113-60 jason protass A Geographic History of Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism: The Decline of the Yunmen Lineage abstract: For a century during China’s Northern Song era, the Yunmen Chan lineage, one of several such regional networks, rose to dominance in the east and north and then abruptly disappeared. Whereas others suggested the decline was caused by a doctri- nal problem, this essay argues that the geopolitics of the Song–Jin wars were the pri- mary cause. The argument builds upon a dataset of Chan abbots gleaned from Flame Records. A chronological series of maps shows that Chan lineages were regionally based. Moreover, Song-era writers knew of regional differences among Chan lin- eages and suggested that regionalism was part of Chan identity: this corroborates my assertion. The essay turns to local gazetteers and early-Southern Song texts that re- cord the impacts of the Song–Jin wars on monasteries in regions associated with the Yunmen lineage. Finally, I consider reasons why the few Yunmen monks who sur- vived into the Southern Song did not reconstitute their lineage, and discuss a small group of Yunmen monks who endured in north China under Jin and Yuan control. keywords: Chan, Buddhism, geographic history, mapping, spatial data n 1101, the recently installed emperor Huizong 徽宗 (r. 1100–1126) I authored a preface for a new collection of Chan 禪 religious biogra- phies, Record of the Continuation of the Flame of the Jianzhong Jingguo Era (Jianzhong Jingguo xudeng lu 建中靖國續燈錄, hereafter Continuation of the Flame).1 The emperor praised the old “five [Chan] lineages, each ex- celling in a family style 五宗各擅家風,” a semimythical system promul- gated by the Chan tradition itself to assert a shared identity among the ramifying branches of master-disciple relationships. -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his. -

The Heart of Prajnaparamita

The Heart of the Prajna Paramita Sutra http://www.io.com/~snewton/zen/heartsut.html Portland Zen Community Primary Zen Texts The Wider Zen Sangha Books to Read Random Thoughts Search these Texts Zen Buddhist Texts Home The free seeing Bodhisattva of compassion, while in profound contemplation of Prajna Paramita, beheld five skandhas as empty in their being and thus crossed over all sufferings. O-oh Sariputra, what is seen does not differ from what is empty, nor does what is empty differ from what is seen; what is seen is empty, what is empty is seen. It is the same for sense perception, imagination, mental function and judgement. O-oh Sariputra, all the empty forms of these dharmas neither come to be nor pass away and are not created or annihilated, not impure or pure, and cannot be increased or decreased. Since in emptiness nothing can be seen, there is no perception, imagination, mental function or judgement. There is no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body or consciousness. Nor are there sights, sounds, odors, tastes, objects or dharmas. There is no visual world, world of consciousness or other world. There is no ignorance or extinction of ignorance and so forth down to no aging and death and also no extinction of aging and death. There is neither suffering, causation, annihilation nor path. There is no knowing or unknowing. Since nothing can be known, Bodhisattvas rely upon Prajna Paramita and so their minds are unhindered. Because there is no hindrance, no fear exists and they are far from inverted and illusory thought and thereby attain nirvana. -

Guangxiao Temple (Guangzhou) and Its Multi Roles in the Development of Asia-Pacific Buddhism

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 8, No. 1; 2016 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Guangxiao Temple (Guangzhou) and its Multi Roles in the Development of Asia-Pacific Buddhism Xican Li1 1 School of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China Correspondence: Xican Li, School of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou Higher Education Mega Center, 510006, Guangzhou, China. Tel: 86-203-935-8076. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 21, 2015 Accepted: August 31, 2015 Online Published: September 2, 2015 doi:10.5539/ach.v8n1p45 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v8n1p45 Abstract Guangxiao Temple is located in Guangzhou (a coastal city in Southern China), and has a long history. The present study conducted an onsite investigation of Guangxiao’s precious Buddhist relics, and combined this with a textual analysis of Annals of Guangxiao Temple, to discuss its history and multi-roles in Asia-Pacific Buddhism. It is argued that Guangxiao’s 1,700-year history can be seen as a microcosm of Chinese Buddhist history. As the special geographical position, Guangxiao Temple often acted as a stopover point for Asian missionary monks in the past. It also played a central role in propagating various elements of Buddhism, including precepts school, Chan (Zen), esoteric (Shingon) Buddhism, and Pure Land. Particulary, Huineng, the sixth Chinese patriarch of Chan Buddhism, made his first public Chan lecture and was tonsured in Guangxiao Temple; Esoteric Buddhist master Amoghavajra’s first teaching of esoteric Buddhism is thought to have been in Guangxiao Temple. -

A Fragment of the Larger Prajñāpāramitā from Central Asia

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies •<>^':% Volume 19 • Number 1 • Summer 1996 JAMIE HUBBARD Mo Fa, The Three Levels Movement, and the Theory of the Three Periods 1 > G. M. BONGARD-LEVIN AND SHIN'ICHIRO HORI A Fragment of the Larger Prajnaparamita from Central Asia 19 ^X NIRMALA S. SALGADO Ways of Knowing and Transmitting Religious Knowledge: Case Studies of TheravSda Buddhist Nuns 61 y< GREGORY SCHOPEN The Lay Ownership of Monasteries and the Role of the Monk in Mulasarvastivadin Monasticism 81 ^ CYRUS STEARNS The Life and Tibetan Legacy of the Indian Mahapandita Vibhuticandra 127 X Books Received 173 G. M. Bongard-Levin and Shin'ichiro Hon A Fragment of the Larger Prajflaparamita from Central Asia INTRODUCTION In the Central Asian Collection of the Manuscript Fund of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences there are approximately 40 fragments belonging to the Pra jflaparamita literature. They were unearthed somewhere in Central Asia and sent to Academician S. F. Oldenburg in St. Petersburg mainly by N. F. Petrovsky, the Russian consul in Kashgar. On the basis of the transliterations made by G. M. Bongard-Levin many of the fragments were identified by Takayasu Kimura, Shin'ichiro Hon and Shogo Watanabe as belonging to the Larger Prajflaparamita.3 This identification opens up new possibilities in the study of this sOtra and the Prajflaparamita literature in general. The whole Skt. text of the Paficavimsatisahasrika Prajflaparamita (hence forth: P) is preserved in late Nepalese manuscripts.4 Besides the complete manuscripts from Nepal, various fragments from Eastern Turkestan, We wish to express our cordial thanks to Professor Dr.