San Antonio and Nacimiento Rivers Watershed Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Report

2350 Mission College Blvd., Suite 525 Santa Clara, CA 95054 650-852-2800 Storm Water Resource Plan For the Greater Salinas Area Final February 10, 2017 Prepared for Monterey Regional Water Pollution Control Agency 5 Harris Court, Building D Monterey, CA 93940 K/J Project No. 1668019*00 Table of Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................ iii List of Figures............................................................................................................................... iii List of Appendices ........................................................................................................................ iv List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... iv Section 1: Introduction and SWRP Objectives .............................................. 6 1.1 Plan Development .................................................................................. 6 1.1 SWRP Plan Objectives........................................................................... 8 1.1.1 GMC IRWM Plan Objectives ..................................................... 11 1.1.1.1 Basin Plan Goals Relevant to Storm Water ............ 11 1.1.2 Greater Salinas Area SWRP Objectives ................................... 11 1.1.2.1 Water Quality Objective .......................................... 12 1.1.2.2 Water Supply Objective ......................................... -

Nacimiento Dam Operation Policy

Nacimiento Dam Operation Policy Monterey County Water Resources Agency Adopted by the Board of Directors February 20, 2018 Recommended by the Reservoir Operations Advisory Committee November 30, 2017 Contents Contents Section I – Introduction and Background ................................................................................ 1 General Description / Information ............................................................................................. 2 Nacimiento River ..................................................................................................................... 2 Nacimiento Dam ..................................................................................................................... 3 Nacimiento Hydroelectric Plant .............................................................................................. 3 Nacimiento Water Project (NWP) ........................................................................................... 4 Pertinent Nacimiento Reservoir Elevations ............................................................................ 4 Section II – Governance and Water Rights .............................................................................. 7 Monterey County Water Resources Agency Board of Supervisors ............................................ 7 Monterey County Water Resources Agency Board of Directors ................................................ 7 Reservoir Operations Advisory Committee ............................................................................... -

Jodi Mcgraw, Ph.D. Population and Community Ecologist PO Box 883 Boulder Creek, CA 95006 (831) 338-1990 [email protected]

RAPID BIOLOGICAL RESOURCE ASSESSMENT FOR THE SALINAS RIVER, MONTEREY COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared By: Jodi McGraw, Ph.D. Population and Community Ecologist PO Box 883 Boulder Creek, CA 95006 (831) 338-1990 [email protected] With Assistance From: Christina Boldero Intern, The Nature Conservancy 201 Mission Street 4th Floor San Francisco, CA 94105 Submitted to: The Nature Conservancy 201 Mission Street 4th Floor San Francisco, CA 94105 April 15, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page List of Tables iv List of Figures v Introduction 1 Section 1: The Physical Environment 4 1.1 Climate 4 1.2 Hydrology 4 1.2.1 Historic Hydrological Conditions 4 1.2.2 Hydrological Alterations 5 1.2.2.1 Dams 5 1.2.2.2 Levees 6 1.2.2.3 Groundwater pumping 6 1.2.2.4 Channel Alterations 7 1.2.2.5 Estuary and Lagoon Alterations 7 1.2.2.5 Other Hydrological Alterations 7 1.2.3 Current Hydrological Conditions 8 1.3 Water Quality 10 1.4 Land Use 10 1.4.1 Historic Land Use 11 1.4.2 Current Land Use 11 1.4.2.1 Agricultural Land 12 1.4.2.2 Urban Areas 13 1.4.3 Current Land Use Changes 13 Section 2: High Priority Species and Communities 13 2.1 Aquatic Communities 13 2.1.1 Coastal Wetlands 13 2.1.2 Freshwater Wetlands 13 2.2 Aquatic Species 14 2.2.1 Pinnacles Riffle Beetle 14 2.2.2 Pacific Lamprey 15 2.2.3 Monterey Roach 16 2.2.4 Sacramento Speckled Dace 16 2.2.5 Steelhead trout 16 2.2.6 California Red-Legged Frog 21 2.2.7 Foothill Yellow-Legged Frog 22 2.2.8 Southwestern pond turtle 22 Salinas River Biological Assessment ii Jodi M. -

Vernal Pool Fairy Shrimp (Branchinecta Lynchi)

fairy shrimp populations are regularly monitored by Bureau of Land Management staff. In the San Joaquin Vernal Pool Region, vernal pool habitats occupied by the longhorn fairy shrimp are protected at the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge. 4. VERNAL POOL FAIRY SHRIMP (BRANCHINECTA LYNCHI) a. Description and Taxonomy Taxonomy.—The vernal pool fairy shrimp (Branchinecta lynchi) was first described by Eng, Belk and Eriksen (Eng et al. 1990). The species was named in honor of James B. Lynch, a systematist of North American fairy shrimp. The type specimen was collected in 1982 at Souza Ranch, Contra Costa County, California. Although not yet described, the vernal pool fairy shrimp had been collected as early as 1941, when it was identified as the Colorado fairy shrimp by Linder (1941). Description and Identification.—Although most species of fairy shrimp look generally similar (see Box 1- Appearance and Identification of Vernal Pool Crustaceans), vernal pool fairy shrimp are characterized by the presence and size of several mounds (see identification section below) on the male's second antennae, and by the female's short, pyriform brood pouch. Vernal pool fairy shrimp vary in size, ranging from 11 to 25 millimeters (0.4 to 1.0 inch) in length (Eng et al. 1990). Vernal pool fairy shrimp closely resemble Colorado fairy shrimp (Branchinecta coloradensis) (Eng et al. 1990). However, there are differences in the shape of a small mound-like feature located at the base of the male's antennae, called the pulvillus. The Colorado fairy shrimp has a round pulvillus, while the vernal pool fairy shrimp's pulvillus is elongate. -

Powder River! Let 'Er Buck!

Fir Tree March, 2012 91st Training Division e-publication POWDER RIVER! LET ‘ER BUCK! 91st Division soldier speaks at Ft. Irwin Huey Retirement page 4 From the Commanding General Fir91st Training DivisionTree Newsletter The 91st Training Division is in full-stride as we ramp up preparations for our summer exercises. The CSM and I plan to visit as many of you as possible over the next Commanding General: few months before the exercises start. A few weeks ago, Brigadier General James T. Cook we had a chance to experience award winning marksman- ship training first-hand while visiting one of the 91st’s Small Arms Readiness Detachments during their Annual Training. Our division is full of talent, so stay-tuned as they compete Office of Public Affairs: in the All-Army Marksmanship Competition. Additionally, 91st Division Soldier honors civilian employer with ESGR we continue to strive for joint certification. We met with the page 5 Director: Commodore of the Navy’s 31st Seabees, Capt. John Korka, and his team to continue our mutual support of their train- Capt. Rebecca Murga ing exercises and integration into our the CSTX and Warrior Exercises. Assistant Director: Please thank your families for their support as you 1st Lt. Fernando Ochoa are away from home more and more through the spring at many workshops and extended meetings. Keep up the great Non Commissioned Officer in Charge: work and stay focused on our goal of providing world class training to the Reserve Forces. Staff Sgt. Jason Hudson Powder River! Editor: Message from the Commanding Gen. & Sgt. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 ONE Official Record of Adoption................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000............................................................ 1-1 1.2 Adoption By Local Governing Bodies and Supporting Documentation ..................................................................................... 1-1 Section 2 TWO Plan Description...................................................................................................................2-1 Section 3 THREE Community Description......................................................................................................3-1 3.1 Location, Geography, and History ........................................................ 3-1 3.2 Demographics ...................................................................................... 3-1 3.3 Land Use and Development Trends ...................................................... 3-2 3.4 Incorporated Communities.................................................................... 3-2 Section 4 FOUR Planning Process.................................................................................................................4-1 4.1 Overview of Planning Process .............................................................. 4-1 4.2 Hazard Mitigation Planning Team........................................................ 4-2 4.2.1 Formation of the Planning Team............................................... 4-2 4.2.2 Planning Team -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Strategic Community Fuelbreak Improvement Project Final Environmental Impact Statement

Final Environmental United States Department of Impact Statement Agriculture Forest Service Strategic Community Fuelbreak May 2018 Improvement Project Monterey Ranger District, Los Padres National Forest, Monterey County, California In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

First 12W Engineer Course at FHL 1-184Th Infantry Regiment Stryker Qualifications

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE FOR U.S. ARMY GARRISON FORT HUNTER LIGGETT/PARKS RESERVE FORCES TRAINING AREA The Golden Guidon First 12W Engineer Course at FHL 1-184th Infantry Regiment Stryker Qualifications www.home.army.mil/liggett | www.home.army.mil/parks Summer 2020 Contents Commander’s Message 3 THE GOLDEN GUIDON Chaplain’s Corner 4 Official Command Publication of U.S. Army Garrison Fort Hunter Liggett/ In the Spotlight 5 Parks Reserve Forces Training Area Garrison Highlights 11 FHL COMMAND TEAM Col. Charles Bell, Garrison Commander Training Highlights 20 David Myhres, Deputy to the Garrison Commander Community Engagements 24 Lt. Col. Stephen Stanley Deputy Garrison Commander Soldier & Employee Bulletin 26 Command Sgt. Major Mark Fluckiger, Garrison Command Sergeant Major PRFTA COMMAND TEAM Lt. Col. Serena Johnson, Features PRFTA Commander Command Sgt. Samuel MacKenzie, • Mesa Del Ray Airport 12 PRFTA Command Sgt. Major • Garrison Asian, Pacific GOLDEN GUIDON STAFF Islanders Share Their Stories 16 Amy Phillips, FHL Public Affairs Officer Jim O’Donnell, PRFTA Public Affairs Officer • It’s What’s Inside the Heart, Cindy McIntyre, Public Affairs Specialist Not the Color That Matters 19 The Golden Guidon is an authorized quarterly publication for the U.S. Army Garrison Fort Hunter Liggett community. Content in this publication is not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government or the Dept. of the Army, or FHL/PRFTA. SUBMISSIONS Guidelines available on the FHL website in the Public Affairs Office section. Submit stories, photographs, and other information to the Public Affairs Office usarmy. COVER PHOTO: California National Army Guard Soldiers with the 1-184th Infantry Regiment from Palmdale, conducting annual Stryker Gunnery Qualifications at Fort hunterliggett.imcom-central.list.fhl-pao @ Hunter Liggett, August 5. -

Monterey County

Steelhead/rainbow trout resources of Monterey County Salinas River The Salinas River consists of more than 75 stream miles and drains a watershed of about 4,780 square miles. The river flows northwest from headwaters on the north side of Garcia Mountain to its mouth near the town of Marina. A stone and concrete dam is located about 8.5 miles downstream from the Salinas Dam. It is approximately 14 feet high and is considered a total passage barrier (Hill pers. comm.). The dam forming Santa Margarita Lake is located at stream mile 154 and was constructed in 1941. The Salinas Dam is operated under an agreement requiring that a “live stream” be maintained in the Salinas River from the dam continuously to the confluence of the Salinas and Nacimiento rivers. When a “live stream” cannot be maintained, operators are to release the amount of the reservoir inflow. At times, there is insufficient inflow to ensure a “live stream” to the Nacimiento River (Biskner and Gallagher 1995). In addition, two of the three largest tributaries of the Salinas River have large water storage projects. Releases are made from both the San Antonio and Nacimiento reservoirs that contribute to flows in the Salinas River. Operations are described in an appendix to a 2001 EIR: “ During periods when…natural flow in the Salinas River reaches the north end of the valley, releases are cut back to minimum levels to maximize storage. Minimum releases of 25 cfs are required by agreement with CDFG and flows generally range from 25-25[sic] cfs during the minimum release phase of operations. -

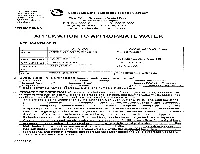

Application to Appropriate Water in Division of Water Rights California") P.O

TYPE OR PRINT IN BLACK INK California Environmental Protection Agency (For instructions, see booklet: "How to File an State Water Resources Control Board Application to Appropriate Water in Division of Water Rights California") P.O. Box 2000, Sacramento, CA 95812-2000 Tel: (916) 341-5300 Fax: (916) 341-5400 APPLICATION NO www. waterboards. ca.gov/waterrights APPLICATION TO APPROPRIATE WATER 1. APPLICANT/AGENT APPLICANT ASSIGNED AGENT (if any) Name Shandon-San Juan Water District Michael Preszler Mailing Address P.O. Box 150 169 Parkshore Drive, Suite 110 City, State & Zip Shandon, CA 93461 Folsom, CA 95630 Telephone (805) 451-0841 (916) 542-7895 Fax E-mail [email protected] [email protected] 2. OWNERSHIP INFORMATION (Please check type of ownership.) Sole Owner _ Limited Liability Company (LLC) _General Partnership* „ Limited Partnership* Business Trust _ Husband/Wife Co-Ownership _ Corporation Joint Venture x Other California Water District *Please identify the names, addresses and phone numbers of all partners. 3. PROJECT DESCRIPTION (Provide a detailed description of your project, including, but not limited to, type of construction activity, area to be graded or excavated, and how the water will be used.) Add additional pages if needed and check box below and label as an attachment. This project is being undertaken by the Shandon-San Juan Water District. The purpose of the project is to augment groundwater supplies in the Paso Robles Area Subbasin (the "Subbasin") by transporting unappropriated water in Lake Nacimiento through the existing Nacimiento Water Project Pipeline (the "Pipeline") to the Subbasin. Water would be delivered to the Subbasin by direct recharge in groundwater recharge facilities that will be constructed, owned and operated by Applicant. -

Santiago Fire

Basin-Indians Fire Basin Complex CA-LPF-001691 Indians Fire CA-LPF-001491 State Emergency Assessment Team (SEAT) Report DRAFT Affecting Watersheds in Monterey County California Table of Contents Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………… Team Members ………………………………………………………………………… Contacts ………………………………………………………..…………………….… Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….. Summary of Technical Reports ……………………………………..………………. Draft Technical Reports ……………………………………………………..…………..…… Geology ……………………………………………………………………...……….… Hydrology ………………………………………………………………………………. Soils …………………………………………………………………………………….. Wildlife ………………………………………………………………….………………. Botany …………………………………………………………………………………... Marine Resources/Fisheries ………………………………………………………….. Cultural Resources ………………………………………………………..…………… List of Appendices ……………………………………………………………………………… Hazard Location Summary Sheet ……………………………………………………. Burn Soil Severity Map ………………………………………………………………… Land Ownership Map ……………………………………………………..…………... Contact List …………………………………………………………………………….. Risk to Lives and Property Maps ……………………………………….…………….. STATE EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT TEAM (SEAT) REPORT The scope of the assessment and the information contained in this report should not be construed to be either comprehensive or conclusive, or to address all possible impacts that might be ascribed to the fire effect. Post fire effects in each area are unique and subject to a variety of physical and climatic factors which cannot be accurately predicted. The information in this report was developed from cursory field