I the RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN TEACHING PHILOSOPHIES AND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applying Andragogy to Promote Active Learning in Adult Education In

SHORT PAPER APPLYING ANDRAGOGY TO PROMOTE ACTIVE LEARNING IN ADULT EDUCATION IN RUSSIA Applying Andragogy to Promote Active Learning in Adult Education in Russia https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v6i4.6079 I.V. Pavlova1 and P.A.Sanger2 1 Kazan National Research Technological University, Kazan, Russian Federation 2 Purdue Polytechnic Institute, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA Abstract—In this rapidly changing world of technology and acquire invaluable experience themselves and by observa- economic conditions, it is essential that practicing engineers tion of others in their environment. This experience gives and engineering educators continue to grow in their skills the learner a rich context for applying new knowledge and and knowledge in order to stay competitive and relevant in new techniques. Therefore, as new programs are devel- the industrial and educational work space. This paper de- oped, the student’s professional experience is a valuable scribes the results for a course that combined the best tech- resource and should be incorporated into the curricular niques of andragogy to promote active learning in a curricu- strategy. Active learning using many of the tools from lum of chemistry education, in particular, chemistry labora- andragogy and project based learning could be an attrac- tory education. This experience with two separate corre- tive approach to capitalize on their experience. spondence classes with similar demographics are reported on. Questionnaires and oral open-ended discussions were II. ACTIVE LEARNING APPROACHES USING used to assess the outcome of this effort. Overall the ap- ANDRAGOGY proach received positive reception while pointing out that correspondence students have full time jobs and active Although the early concepts on adult education go back learning in general requires more effort and time. -

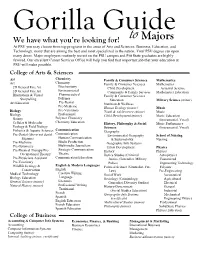

Gorilla Guide for Majors Activity

Gorilla Guide Gorilla Guide We have what you’re looking for! to Majors At PSU you may choose from top programs in the areas of Arts and Sciences, Business, Education, and Technology, many that are among the best and most specialized in the nation. Your PSU degree can open many doors. Major employers routinely recruit on the PSU campus and Pitt State graduates are highly favored. Our excellent Career Services Office will help you find that important job that your education at PSU will make possible. College of Arts & Sciences Art Chemistry Family & Consumer Sciences Mathematics Art Chemistry Family & Consumer Sciences Mathematics 2D General Fine Art Biochemistry Child Development Actuarial Science 3D General Fine Art Environmental Community & Family Services Mathematics Education Illustrations & Visual Pharmaceutical Family & Consumer Sciences Storytelling Polymer Education Military Science (minor) Art Education Pre-Dental Nutrition & Wellness Pre-Medicine Human Ecology (minor) Music Biology Pre-Veterinary Youth & Adolescence (minor) Music Biology Professional Child Development (minor) Music Education Botany Polymer Chemistry (Instrumental, Vocal) Cellular & Molecular Chemistry Education History, Philosophy & Social Music Performance Ecology & Field Biology Sciences (Instrumental, Vocal) Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences Communication Geography Pre-Dental (this is not dental Communication Environmental Geography School of Nursing hygiene) Human Communication & Sustainability Nursing Pre-Medicine Media Production Geographic Info Systems Pre-Optometry -

Catalog 2011-12

C A T A L O G 1 2011 2012 Professional/Technical Careers University Transfer Adult Education 2 PIERCE COLLEGE CATALOG 2011-12 PIERCE COLLEGE DISTRICT 11 BOARD OF TRUSTEES DONALD G. MEYER ANGIE ROARTy MARC GASPARD JAQUELINE ROSENBLATT AMADEO TIAM Board Chair Vice Chair PIERCE COLLEGE EXECUTIVE TEAM MICHELE L. JOHNSON, Ph.D. Chancellor DENISE R. YOCHUM PATRICK E. SCHMITT, Ph. D. BILL MCMEEKIN President, Pierce College Fort Steilacoom President, Pierce College Puyallup Interim Vice President for Learning and Student Success SUZY AMES Executive Vice President Vice President for Advancement of Extended Learning Programs Executive Director of the Pierce College Foundation JO ANN W. BARIA, Ph. D. Dean of Workforce Education JAN BUCHOLZ Vice President, Human Resources DEBRA GILCHRIST, Ph.D. Dean of Libraries and Institutional Effectiveness CAROL GREEN, Ed.D. Vice President for Learning and Student Success, Fort Steilacoom MICHAEL F. STOCKE Dean of Institutional Technology JOANN WISZMANN Vice President, Administrative Services The Pierce College District does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, disability, or age in its programs and activities. Upon request, this publication will be made available in alternate formats. TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Table of Contents Landscapes of Possibilities Dental Hygiene ......................................................52 Sociology ..................................................................77 Chancellor’s Message ..............................................5 -

What Lies Behind Teaching and Learning Green Chemistry to Promote Sustainability Education? a Literature Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review What Lies Behind Teaching and Learning Green Chemistry to Promote Sustainability Education? A Literature Review Meiai Chen 1 , Eila Jeronen 2 and Anming Wang 3,* 1 School of Tourism & Health, Zhejiang A&F University, Hangzhou 311300, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Educational Sciences and Teacher Education, University of Oulu, FI-90014 Oulu, Finland; eila.jeronen@oulu.fi 3 College of Materials, Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 311121, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 11 September 2020; Accepted: 24 October 2020; Published: 27 October 2020 Abstract: In this qualitative study, we aim to identify suitable pedagogical approaches to teaching and learning green chemistry among college students and preservice teachers by examining the teaching methods that have been used to promote green chemistry education (GCE) and how these methods have supported green chemistry learning (GCL). We found 45 articles published in peer-reviewed scientific journals since 2000 that specifically described teaching methods for GCE. The content of the articles was analyzed based on the categories of the teaching methods used and the revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy. Among the selected articles, collaborative and interdisciplinary learning, and problem-based learning were utilized in 38 and 35 articles, respectively. These were the most frequently used teaching methods, alongside a general combination of multiple teaching methods and teacher presentations. Developing collaborative and interdisciplinary learning skills, techniques for increasing environmental awareness, problem-centered learning skills, and systems thinking skills featuring the teaching methods were seen to promote GCL in 44, 40, 34, and 29 articles, respectively. -

BS in Chemistry Education

BS in Chemistry Education (692828) MAP Sheet Physical and Mathematical Sciences, Chemistry and Biochemistry For students entering the degree program during the 2021-2022 curricular year. This major is designed to prepare students to teach in public schools. In order to graduate with this major, students are required to complete Utah State Office of Education licensing requirements. To view these requirements go to http://education.byu.edu/ess/licensing.html or contact Education Advisement Center, 350 MCKB, 801-422-3426. University Core and Graduation Requirements Suggested Sequence of Courses University Core Requirements: FRESHMAN YEAR JUNIOR YEAR Requirements #Classes Hours Classes 1st Semester 5th Semester CHEM 111* (F) 4.0 CHEM 462 (F) or other Req. #4 3.0 Religion Cornerstones First-year Writing or A HTG 100 (FWSpSu) 3.0 IP&T 371 1.0 Teachings and Doctrine of The Book of 1 2.0 REL A 275 MATH 112 (FWSpSu) 4.0 IP&T 373 1.0 Mormon PWS 150** (FW) or other Requirement #5 3.0 SC ED 353 3.0 Religion Cornerstone course 2.0 PHIL 423* or Requirement 5 3.0 Jesus Christ and the Everlasting Gospel 1 2.0 REL A 250 Total Hours 16.0 Religion elective 2.0 Foundations of the Restoration 1 2.0 REL C 225 *With department approval, CHEM 105 may be substituted for CHEM Open Elective 2.5 Total Hours 15.5 The Eternal Family 1 2.0 REL C 200 111. The Individual and Society **PWS 150 fulfills Requirement #5 and G.E. Biological Sciences. If *PHIL 423 fulfills Requirement #5 and G.E. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Chemistry Education Research and Practice Accepted Manuscript

Chemistry Education Research and Practice Accepted Manuscript This is an Accepted Manuscript, which has been through the Royal Society of Chemistry peer review process and has been accepted for publication. Accepted Manuscripts are published online shortly after acceptance, before technical editing, formatting and proof reading. Using this free service, authors can make their results available to the community, in citable form, before we publish the edited article. We will replace this Accepted Manuscript with the edited and formatted Advance Article as soon as it is available. You can find more information about Accepted Manuscripts in the Information for Authors. Please note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the text and/or graphics, which may alter content. The journal’s standard Terms & Conditions and the Ethical guidelines still apply. In no event shall the Royal Society of Chemistry be held responsible for any errors or omissions in this Accepted Manuscript or any consequences arising from the use of any information it contains. www.rsc.org/cerp Page 1 of 15 Chemistry Education Research and Practice 1 2 Chemistry Education Research and Practice RSCPublishing 3 4 5 ARTICLE 6 7 8 9 Education for sustainable development in chemistry 10 – Challenges, possibilities and pedagogical models in Manuscript 11 Cite this: DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x 12 Finland and elsewhere 13 14 15 Received 00th April 2014, 16 th Accepted 00 April 2014 M.K. Juntunen,a M.K. Akselab, 17 18 DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x 19 This article analyses Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in chemistry by reviewing existing www.rsc.org/ 20 challenges and future possibilities on the levels of the teacher and the student. -

Victor Leander Roy, Louisiana Educator. Douglas Calvin Westbrook Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1970 Victor Leander Roy, Louisiana Educator. Douglas Calvin Westbrook Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Westbrook, Douglas Calvin, "Victor Leander Roy, Louisiana Educator." (1970). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1900. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1900 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I 71-10,593 WESTBROOK, Douglas Calvin, 1927- VICTOR LEANDER ROY, LOUISIANA EDUCATOR. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ed.D., 1970 Education, history University Microfilms, A XEROX Company , Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED VECTOR LEANDER ROY , LOUISIANA EDUCATOR A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in The Department of Education by Douglas Calvin Westbrook B.S., Northwestern State College, 1949 .A., Colorado State College of Education, 1953 August, 1970 EXAMINATION AND THESIS REPORT Candidate: Douglas Calvin Westbrook Major Field: Education Title of Thesis: Victor Leander Roy, Louisiana Educator Approved: Major ProfMsor and Chairman Dean of the Graduate School EXAMINING COMMITTEE: 4, Date of Examination: July 22j 1970 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer acknowledges with gratitude the assis tance received from many persons and from the following in particular: the head of his committee, Dr. -

Chemistry Education 7-12 Effective 2019-2020 Academic Year

NAME: ID#: Bulletin year: Chemistry Education 7-12 Effective 2019-2020 academic year #could be taken for credit towards an International Studies minor I. ACHIEVEMENT CENTERED EDUCATION (ACE) III. ENDORSEMENT All UNL students are required to complete a minimum of 3 hours of approved No grade lower than “C” course work in each of the 10 designated ACE areas. Students must complete a minimum of 24 hours in chemistry from the following ACE #1 Written Texts Incorporating Research & Knowledge Skills list plus a minimum of 4 hours each in biology, physics, and earth & space ENGL150, 151, or 254 (3 hrs) science. ACE #2 Communication Skills CHEM 109 General Chemistry I (4 hrs) TEAC 259 (3 hrs) √√√√√ CHEM 110 General Chemistry II (4 hrs) CHEM 221 Elementary Quantitative Analysis (4 hrs) ACE #3 Mathematical, Computational, Statistical, or Formal Reasoning Skills MATH 106, STAT 218 or EDPS 459 (3 hrs) Select one of the following: (4 hrs) CHEM 251/253 Organic Chemistry w/lab OR CHEM 255/257 Biologic Organic Chemistry w/lab ACE #4 Study of Scientific Methods & Knowledge of Natural & Physical World LIFE 120/120L (4 hrs) √√√√√ CHEM 421/423 Analytical Chemistry w/lab (5 hrs) Offered Spring semester only ACE #5 Study of Humanities (Prerequisite: Chem 471 or 481) (Any) (3 hrs) CHEM 441/443 Inorganic Chemistry w/lab (4 hrs) ACE #6 Study of Social Sciences EDPS 251 (3 hrs) √√√√√ Select one of the following: (4 hrs) CHEM 471 Physical Chemistry OR ACE #7 Study of the Arts to Understand Their Context & Significance (Prerequisite: Chem 221, Math 107) (Any) (3 -

Models and Modelling in Chemistry Education in the Higher Medical Education System Assos

Science & Research MODELS AND MODELLING IN CHEMISTRY EDUCATION IN THE HIGHER MEDICAL EDUCATION SYSTEM ASSOS. PROF. DR. V. HADZHIILIEV Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Medical Faculty, Trakia University - Stara Zagora, Bulgaria; [email protected] Abstract: The objective of this paper is to consider the "classical" forms of training in higher medical school and try to give a new reading of the organizational forms of training, updated by the modern requirements addressed to the higher education institutions in Bulgaria, after adoption of the credit accumulation and transfer system. The compulsory training, which meets the requirements of the MILC, shall be conditionally made module A. Under this module, students attend both forms of training – lectures and practical exercises. The second group of activities builds on the knowledge and skills to be included in module C. This activity is built only on a type A activity already carried out, including free-elective and optional preparation in Chemistry. The formation of scientific competencies is carried out through direct scientific work, including literature review, searching for a suitable methodology for work, drawing up an experimental plan, reporting and analyzing the results of a real experiment (module C). This activity builds on the previous two and includes elements of reproduction and creativity. Keywords: medical pedagogy, models, modelling. Models and modelling. The word "model" has a Latin origin, derived from "modus", which means image, measure, ability. The initial use is in construction (architecture) to denote different types of samples. Its use in Mathematics began after the creation of Analytic geometry by Descartes and Fermat. In Natural sciences (Biology, Chemistry and Physics), the term "model" began to be used to refer to the object a particular theory refers to or it describes. -

Science Education Courses 1

Science Education Courses 1 Science Education Courses Courses SIED 5312. Environmental Education. Critical examination of pedagogical techniques, curricula and standards associated with environmental education. Special emphasis is placed on human induced environmental change, curriculum development and teaching in environmental education settings. All components of the course are focused on increasing the student's ability to be a highly effective environmental educator. This course includes guest speakers and single day field trips in local environments. Department: Science Education 3 Credit Hours 3 Total Contact Hours 0 Lab Hours 3 Lecture Hours 0 Other Hours SIED 5321. Sc Tools Stnd Tech Safty/Ethic. Science Tools, Standards, Technology, Safety and Ethics (3-0) Integrated, science-technology thematic learning. Develops understanding of important science teacher resources, basic science education and lab tools, state and national standards for science teaching, curriculum alignment, laboratory and classroom safety, and professional ethics for science educators. Department: Science Education 3 Credit Hours 3 Total Contact Hours 0 Lab Hours 3 Lecture Hours 0 Other Hours SIED 5323. Societal Context of Sc Educ. Societal Context of Science Education (3-0) Develops and applies understanding of field, community, and cultural resources and develop family and community partnerships in a relevant science context. Students develop a learning unit based on instructional models such as the learning cycle lesson design and the 5-E model. Explores historical perspectives of science and the role of science in societal decisions. Includes research-based principles in science learning and technology integration. Department: Science Education 3 Credit Hours 3 Total Contact Hours 0 Lab Hours 3 Lecture Hours 0 Other Hours SIED 5325. -

Nature of Science and Chemistry Education

The Nature of Chemistry as a Science – Inquiry-Based Learning of Chemistry LUMAT-B 1(3) 2016 Nature of science and chemistry education Veli-Matti Vesterinen Learning and teaching laboratory, Department of Chemistry, University of Turku, Turku, Finland Abstract: Nature of science (NOS) is widely recognized as one of the key aims of chemistry education. The purpose of this paper is to describe the importance of teaching NOS as well as to discuss the role of NOS in sustainable chemistry education. Keywords: chemistry as a science, nature of science, technology Cite: Vesterinen, V.-M. (2016). Nature of science and chemistry education. LUMAT-B: International Journal on Math, Science and Technology Education, 1(3). Scientific literacy and nature of science The concept scientific literacy was introduced in the late 1950s. Although it initially focused on improving the public understanding of science and support for science and industrial programs, during the following decades the concept was debated and reconceptualized countless times. During the 1960s and 1970s, the new academic knowledge of science and technology studies deeply challenged the traditional positivist view of science portrayed on curricula and science textbooks. The historical, philosophical and sociological analysis of the scientists’ work provided a new view of science as a socially embedded enterprise. Eventually, this new view of science studies had an effect also on school science education. Inspired by the new academic research on science and technology studies as well as environmental and civil rights movements, in the late 1970s and 1980s the social context and science-technology- society (STS) movement began influencing the conceptualizations of scientific literacy.