Mridang a View of the Siddha Yoga Drum from the Perspective of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Readying the Purnahutis, to Dressing of 11 Rudrams, Accompanied the Devi and Every Murthi Inside by Bilva Archana for 11 Shiva the Temple

Sri Chakra The Source of the Cosmos The Journal of the Sri Rajarajeswari Peetam, Rush, NY Blossom 13 Petal 1 March 2009 Om Nama Shivaya... MarchMarch NewsletterNewsletter Since the last issue... The beginning of December saw Aiya come up to Toronto to teach the kids’ class and Kitchener/ Waterloo to teach a class and make personal visits. He was back in Rochester for Karthikai Deepam on Dec. 11. The temple hosted large crowds later in the month when it Clockwise from top: Aiya was hosted a Rudra homam workshop honoured by Nemili Ezhilmani; on the 27th and the annual kids’ Annamalai temple and mountain; Aiya Matangi homam on the 28th. and Amma at the conference; Aiya The next big event after that was delivering his address on mantra, tantra and yantra; our gurus hanging Thiruvempavai for the first 10 days out with their gurus. of 2009. After Ardhra Dharshanam, Aiya and Amma briefly visited Delaware before embarking on a two-week trip to India. Satpurananda. They were in Kanchipuram and After the conference, Amma and Nemili on the 16th, where they Aiya flew to Visakapatnam to see received a wonderful welcome. Ammah and Guruji and also to Aiya’s rendition of Bala Kavacham visit Devipuram. After that, they was playing as they entered the went to kumbhakonam and later Nemili peetam. From there, Amma met Sri Shangaranarayanan to and Aiya went to Thiruvannamalai, discuss items needed for the SVTS and then Chidambaram. kumbhabhishekam in 2010. They then came back to Upon returning from India on Chennai, where they visited the evening of Jan. -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover next page > title: Indian Music and the West : Gerry Farrell author: Farrell, Gerry. publisher: Oxford University Press isbn10 | asin: 0198167172 print isbn13: 9780198167174 ebook isbn13: 9780585163727 language: English subject Music--India--History and criticism, Music--Indic influences, Civilization, Western--Indic influences, Ethnomusicology. publication date: 1999 lcc: ML338.F37 1999eb ddc: 780.954 subject: Music--India--History and criticism, Music--Indic influences, Civilization, Western--Indic influences, Ethnomusicology. cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i Indian Music and the West < previous page page_i next page > < previous page page_ii next page > Page ii To Jane < previous page page_ii next page > < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii Indian Music and the West Gerry Farrell OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS < previous page page_iii next page > < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Gerry Farrell 1997 First published 1997 New as paperback edition 1999 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) All rights reserved. -

Musical Instruments of South Asian Origin Depicted on the Reliefs at Angkor, Cambodia

Musical instruments of South Asian origin depicted on the reliefs at Angkor, Cambodia EURASEAA, Bougon, 26th September, 2006 and subsequently revised for publication [DRAFT CIRCULATED FOR COMMENT] Roger Blench Mallam Dendo Ltd. 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Cambridge, Monday, 02 July 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION: MUSICAL ICONOGRAPHY IN SE ASIA..................................................................1 2. MUSICAL ICONOGRAPHY AT ANGKOR ................................................................................................1 3. THE INSTRUMENTS......................................................................................................................................2 3.1 Idiophones.....................................................................................................................................................................2 3.2 Drums............................................................................................................................................................................3 3.3 Strings ...........................................................................................................................................................................4 3.4 Wind instruments.........................................................................................................................................................5 -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Hindu Patrika

Board of Trustees C HINDU PATRIKAC Term Name Published 2009-2011 Vishal Adma Chairman Bimonthly 2010-2012 Deb Bhaduri Vice Chair DECEMBER/JANUARY 2012 Vol 17/2011 2009-2011 Sanjeev Goyal 2009-2011 Mahendra Sheth 2010-2012 Sadhana Bisarya 2010-2012 Sanjay Mishra 2009-2011 Vishal Adma 2010-2012 Manu Rattan 2011-2013 Mohan Gupta 2011-2013 Priti Mohan 2011-2013 Govind Patel 2011-2013 Mana Pattanayak 2011-2013 Eashwer Reddy 2011 Neelam Kumar 2011 Sridhar Harohalli Vision of HTCC To promote Hinduism’s spiritual and cultural legacy of inspiration and optimism for the larger Kansas City community. Mission of HTCC • Create an environment of worship that enables people to say “yes” to the love of God. • Cultivate a community that nurtures spiritual growth. • Commission every devotee to serve the creation through their unique talents and gifts. • Coach our youth with the spiritual and cultural richness and the diversity they are endowed with • Communicate Hinduism – A way of life to everyone we can and promote inter-faith activities with equal veneration Hindu Temple & Cultural Center of Kansas Hindu Temple Wishes a Very Happy New Year to all the City Members A NON-PROFIT TEMPLE HOURS Day Time Aarti ORGANIZATION Mon - Fri 10:00am-12:00pm 11:00am Please remember to renew your annual membership which runs from January to 6330 Lackman Road Mon - Fri 5:00pm-8:00pm 7:30pm Shawnee, KS 66217-9739 Sat & Sun 9:00am-8:00pm 12:00pm December. Sat & Sun 7:30pm http://www.htccofkc.org Your Current membership status is printed on the mailing label. -

A) Indian Music (Hindustani) (872

MUSIC Aims: One of the three following syllabuses may be offered: 1. To encourage creative expression in music. 2. To develop the powers of musical appreciation. (A) Indian Music (Hindustani) (872). (B) Indian Music (Carnatic) (873). (C) Western Music (874). (A) INDIAN MUSIC (HINDUSTANI) (872) (May not be taken with Western Music or Carnatic Music) CLASSES XI & XII The Syllabus is divided into three parts: PAPER 2: PRACTICAL (30 Marks) Part 1 (Vocal), The practical work is to be evaluated by the teacher and a Visiting Practical Examiner appointed locally Part 2 (Instrumental) and and approved by the Council. Part 3 (Tabla) EVALUATION: Candidates will be required to offer one of the parts Marks will be distributed as follows: of the syllabus. • Practical Examination: 20 Marks There will be two papers: • Evaluation by Visiting Practical 5 Marks Paper 1: Theory 3 hours ….. 70 marks Examiner: Paper 2: Practical ….. 30 marks. (General impression of total Candidates will be required to appear for both the performance in the Practical papers from one part only. Examination: accuracy of Shruti and Laya, confidence, posture, PAPER 1: THEORY (70 Marks) tonal quality and expression) In the Theory paper candidates will be required to • Evaluation by the Teacher: 5 Marks attempt five questions in all, two questions from Section A (General) and EITHER three questions (of work done by the candidate from Section B (Vocal or Instrumental) OR three during the year). questions from Section C (Tabla). NOTE: Evaluation of Practical Work for Class XI is to be done by the Internal Examiner. 266 CLASS XI PART 1: VOCAL MUSIC PAPER 1: THEORY (70 Marks) The above Ragas with special reference to their notes Thaat, Jaati, Aaroh, Avaroh, Pakad, Vadi, 1. -

MULTI-FACETED VEDIC HINDUISM Introduction

MULTI-FACETED VEDIC HINDUISM M.G. Prasad Introduction Life in the universe is a wonderful mystery. Human beings have the privilege of seeking, understanding and experiencing the mystery of life. In a triadic approach based on the Vedas, existence of life can be described as God (Ishwara), Universe (Jagat) and individual (Jeeva). Any individual human being could see the universe as an entity that consists of all beings including other individuals and nature. The GOD as Supreme Being is seen as a free and independent entity responsible for Generation, Operation and Dissolution of everything in the universe and all beings. Thus it can be seen that One God as Bramhan with all attributes is the unitary source of all manifestations. Any human being is eligible to make connection with this One Source from which all knowledge manifest. The multi-faceted knowledge emanating from this One Source is referred as Vedas, which is infinite and eternal. This infinite body of knowledge as Vedas and Vedic literature can be represented as an inverted tree shown in figure 1 and also referred in Bhagavadgita (15-1). Figure 1: Inverted tree This inverted tree representation can be used to describe the multi-faceted Vedic Hinduism (Sanatana dharma). In Vishnusahasranama, we have the verse: Yogo jnanam tathaa sankhyam vidya shilpadi karma cha Vedaa shastraani vijnanam etatt sarvam Janardhanat Which means that yoga, all types of knowledge, art, sculptures, rituals, Vedas, Vedic scriptures and science have emanated from Janardhana denoting One Source. Thus, this multi-faceted nature of Vedic Hinduism or Sanatana Dharma offers the seekers with diverse aptitudes several pathways to approach that One Source of Light and Bliss. -

Paper - Iii Music

SF,T 2016 PAPER - III MUSIC Signature ofthe Invigilator Question. Booklet No . ..........27001................4 .......... 1. OMR Sheet No .. ................................ .... Subject Code [;;] ROLL No. Time Allowed : 150 Minutes Max. Marks: 150 l No. of pages in this Booklet : 16 No. of Questions: 75 INSTRUCTIONS FOR CANDIDATES 1. Write your Roll No. and the OMR Sheet No. in the spaces provided on top oft his page. 2. Fill in the necessary information in the spaces provided on the OMR response sheet. 3. This booklet consists of seventy five (7 5) compulsory questions each carrying 2 marks. 4. Examine the question booklet carefully and tally the number ofpages /questions in the booklet with the information printed above. Do not accept a damaged or open booklet. Damaged or faulty boo !<Jet may be got replaced within the first 5 minutes. Afterwards, neither the Question Booklet will be replaced nor any extra エゥュセ@ given. 5. Each Question has four alternative responses marked (A), (B), (C) and (D) in the OMR sheet. You have to completely darken the circle indicating the most appropriate response against each item as in the illustration : 6. All entries in the OMR.response sheet are to be recorded in the original copy only. 7. Use only Blue/Black Ball point pen. l 8. Rough Work is to be done on the blank pages provided at the end of this booklet. 9. Ifyou write your Name, Roll Number, Phone Number or put any mark on any part of the OMR Sheet, except in the spaces allotted for the relevant entries, which may disclose your identity, or use abusive language or employ any other unfair means, you will render yourselfliable todisq ualification. -

Om: One God Universal a Garland of Holy Offerings * * * * * * * * Viveka Leads to Ānanda

Om: One God Universal A Garland of Holy Offerings * * * * * * * * Viveka Leads To Ānanda VIVEKNANDA KENDRA PATRIKĀ Vol. 22 No. 2: AUGUST 1993 Represented By Murari and Sarla Nagar Truth is One God is Truth . God is One Om Shanti Mandiram Columbia MO 2001 The treasure was lost. We have regained it. This publication is not fully satisfactory. There is a tremendous scope for its improvement. Then why to publish it? The alternative was to let it get recycled. There is a popular saying in American academic circles: Publish or Perish. The only justification we have is to preserve the valuable contents for posterity. Yet it is one hundred times better than its original. We have devoted a great deal of our time, money, and energy to improve it. The entire work was recomposed on computer. Figures [pictures] were scanned and inserted. Diacritical marks were provided as far as possible. References to citations were given in certain cases. But when a vessel is already too dirty it is very difficult to clean it even in a dozen attempts. The original was an assemblage of scattered articles written by specialists in their own field. Some were extracted from publications already published. It was issued as a special number of a journal. It needed a competent editor. Even that too was not adequate unless the editor possessed sufficient knowledge of and full competence in all the subject areas covered. One way to make it correct and complete was to prepare a kind of draft and circulate it among all the writers, or among those who could critically examine a particular paper in their respective field. -

T>HE JOURNAL MUSIC ACADEMY

T>HE JOURNAL OF Y < r f . MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY IrGHTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE ' AND ART OF MUSIC XXXVIII 1967 Part.' I-IV ir w > \ dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, ^n- the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there L ^ Narada ! ” ) EDITED BY v. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1967 PUBLISHED BY 1US1C ACADEMY, MADRAS a to to 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD, MADRAS-14 bscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. X \ \ !• ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES \ COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page i BaCk (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 99 20 .. 11. BaCk (Do.) 30 *# ” J6 INSIDE PAGES: i 1st page (after Cover) 99 18 io Other pages (eaCh) 99 15 .. 9 PreferenCe will be given (o advertisers of musiCal ® instruments and books and other artistic wares. V Special positions and speCial rates on appliCation. t NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Ragb Editor, Journal of the MusiC ACademy, Madras-14. Articles on subjects of musiC and dance are accepte publication on the understanding that they are Contributed to the Journal of the MusiC ACademy. f. AIT manuscripts should be legibly written or preferabl; written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and be sigoed by the writer (giving his address in full). I The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for tb expressed by individual contributors. AH books, advertisement moneys and cheques du> intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V, B Editor. CONTENTS Page T XLth Madras MusiC Conference, 1966 OffiCial Report .. -

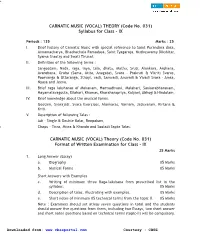

CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL) THEORY (Code No

CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL) THEORY (Code No. 031) Syllabus for Class - IX Periods : 135 Marks : 25 I. Brief history of Carnatic Music with special reference to Saint Purandara dasa, Annamacharya, Bhadrachala Ramadasa, Saint Tyagaraja, Muthuswamy Dikshitar, Syama Shastry and Swati Tirunal. II. Definition of the following terms : Sangeetam, Nada, raga, laya, tala, dhatu, Mathu, Sruti, Alankara, Arohana, Avarohana, Graha (Sama, Atita, Anagata), Svara - Prakruti & Vikriti Svaras, Poorvanga & Uttaranga, Sthayi, vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi & Vivadi Svara - Amsa, Nyasa and Jeeva. III. Brief raga lakshanas of Mohanam, Hamsadhvani, Malahari, Sankarabharanam, Mayamalavagoula, Bilahari, Khamas, Kharaharapriya, Kalyani, Abhogi & Hindolam. IV. Brief knowledge about the musical forms. Geetam, Svarajati, Svara Exercises, Alankaras, Varnam, Jatisvaram, Kirtana & Kriti. V. Description of following Talas : Adi - Single & Double Kalai, Roopakam, Chapu - Tisra, Misra & Khanda and Sooladi Sapta Talas. CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL) Theory (Code No. 031) Format of Written Examination for Class - IX 25 Marks 1. Long Answer (Essay) a. Biography 05 Marks b. Musical Forms 05 Marks Short Answers with Examples c. Writing of minimum three Raga-lakshana from prescribed list in the syllabus. 05 Marks d. Description of talas, illustrating with examples. 05 Marks e. Short notes of minimum 05 technical terms from the topic II. 05 Marks Note : Examiners should set atleas seven questions in total and the students should answer five questions from them, including two Essays, two short answer and short notes questions based on technical terms (topic-II) will be compulsory. Downloaded from: www.cbseportal.com Courtesy : CBSE 101 CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL) Practical (Code No. 031) Syllabus for Class - IX Periods : 405 Marks : 75 I. Vocal exercises - Svaravalis, Hechchu and Taggu Sthayi, Alankaras in three degrees of speed. -

Annual Report 1990 .. 91

SANGEET NAT~AKADEMI . ANNUAL REPORT 1990 ..91 Emblem; Akademi A wards 1990. Contents Appendices INTRODUCTION 0 2 Appendix I : MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION (EXCERPTS) 0 53 ORGANIZATIONAL SET-UP 05 AKADEMI FELLOWSHIPS/ AWARDS Appendix II : CALENDAR OF 19900 6 EVENTS 0 54 Appendix III : GENERAL COUNCIL, FESTIVALS 0 10 EXECUTIVE BOARD, AND THE ASSISTANCE TO YOUNG THEATRE COMMITTEES OF THE WORKERS 0 28 AKADEMID 55 PROMOTION AND PRESERVATION Appendix IV: NEW AUDIO/ VIDEO OF RARE FORMS OF TRADITIONAL RECORDINGS 0 57 PERFORMING ARTS 0 32 Appendix V : BOOKS IN PRINT 0 63 CULTURAL EXCHANGE Appendix VI : GRANTS TO PROGRAMMES 0 33 INSTITUTIONS 1990-91 064 PUBLICATIONS 0 37 Appendix VII: DISCRETIONARY DOCUMENTATION / GRANTS 1990-91 071 DISSEMINATION 0 38 Appendix VIll : CONSOLIDATED MUSEUM OF MUSICAL BALANCE SHEET 1990-91 0 72 INSTRUMENTS 0 39 Appendix IX : CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE TO SCHEDULE OF FIXED CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS 0 41 ASSETS 1990-91 0 74 LIBRARY AND LISTENING Appendix X : PROVIDENT FUND ROOMD41 BALANCE SHEET 1990-91 078 BUDGET AND ACCOUNTS 0 41 Appendix Xl : CONSOLIDATED INCOME & EXPENDITURE IN MEMORIAM 0 42 ACCOUNT 1990-91 KA THAK KENDRA: DELHI 0 44 (NON-PLAN & PLAN) 0 80 JA WAHARLAL NEHRU MANIPUR Appendix XII : CONSOLIDATED DANCE ACADEMY: IMPHAL 0 50 INCOME & EXPENDITURE ACCOUNT 1990-91 (NON-PLAN) 0 86 Appendix Xlll : CONSOLIDATED INCOME & EXPENDITURE ACCOUNT 1990-91 (PLAN) 0 88 Appendix XIV : CONSOLIDATED RECEIPTS & PAYMENTS ACCOUNT 1990-91 (NON-PLAN & PLAN) 0 94 Appendix XV : CONSOLIDATED RECEIPTS & PAYMENTS ACCOUNT 1990-91 (NON-PLAN) 0 104 Appendix XVI : CONSOLIDATED RECEIPTS & PAYMENTS ACCOUNT 1990-91 (PLAN) 0 110 Introduction Apart from the ongoing schemes and programmes, the Sangeet Natak Akademi-the period was marked by two major National Academy of Music, international festivals presented Dance, and Drama-was founded by the Akademi in association in 1953 for the furtherance of with the Indian Council for the performing arts of India, a Cultural Relations.