Clean Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tongass National Forest

S. Hrg. 101-30, Pt. 3 TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PUBLIC LANDS, NATIONAL PARKS AND FORESTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIRST CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 987 *&< TO AMEND THE ALASKA NATIONAL INTEREST LANDS CONSERVATION ACT, TO DESIGNATE CERTAIN LANDS IN THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST AS WILDERNESS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES FEBRUARY 26, 1990 ,*ly, Kposrretr PART 3 mm uwrSwWP Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources Boston P«*5!!c y^rary Boston, MA 116 S. Hrg. 101-30, Pr. 3 TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PUBLIC LANDS, NATIONAL PAEKS AND FORESTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIRST CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 987 TO AMEND THE ALASKA NATIONAL INTEREST LANDS CONSERVATION ACT, TO DESIGNATE CERTAIN LANDS IN THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST AS WILDERNESS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES FEBRUARY 26, 1990 PART 3 Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 29-591 WASHINGTON : 1990 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES J. BENNETT JOHNSTON, Louisiana, Chairman DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas JAMES A. McCLURE, Idaho WENDELL H. FORD, Kentucky MARK O. HATFIELD, Oregon HOWARD M. METZENBAUM, Ohio PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BILL BRADLEY, New Jersey MALCOLM WALLOP, Wyoming JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico FRANK H. MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIMOTHY E. WIRTH, Colorado DON NICKLES, Oklahoma KENT CONRAD, North Dakota CONRAD BURNS, Montana HOWELL T. -

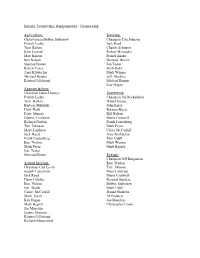

Congressional Committees Roster

HOUSE AND SENATE COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP Provided below are House and Senate Committee membership rosters with jurisdiction over health programs as of Friday, November 17, 2006. At the time of this printing, only the Senate Democrats have released their Committee assignments. Assignments for the House Committees will not take place until December when Congress reconvenes in the lame-duck session. However, most Members of Congress who were on the Committees before the election will continue to serve. Members whose names are crossed out will not be returning in the 110th Congress. Members whose names are underlined, indicates that they have been added to the Committee. Senate Appropriations Committee Majority Minority Robert C. Byrd, WV - Chair Thad Cochran, MS - Rnk. Mbr. Daniel K. Inouye, HI Ted Stevens, AK Patrick J. Leahy, VT Arlen Specter, PA Tom Harkin, IA Pete V. Domenici, NM Barbara A. Mikulski, MD Christopher S. Bond, MO Harry Reid, NV Mitch McConnell, KY Herbert H. Kohl, WI Conrad Burns, MT Patty Murray, WA Richard C. Shelby, AL Byron L. Dorgan, ND Judd Gregg, NH Dianne Feinstein, CA Robert F. Bennett, UT Richard J. Durbin, IL Larry Craig, ID Tim P. Johnson, SD Kay Bailey Hutchison, TX Mary L. Landrieu, LA Mike DeWine, OH Jack Reed, RI Sam Brownback, KS Frank Lautenberg NJ Wayne A. Allard, CO Ben Nelson, NE Senate Budget Committee Majority Minority Kent Conrad, ND - Chair Judd Gregg, NH - Rnk. Mbr. Paul S. Sarbanes, MD Pete V. Domenici, NM Patty Murray, WA Charles E. Grassley, IA Ron Wyden, OR Wayne A. Allard, CO Russ Feingold, WI Michael B. -

Bio for Jeff.Docx

Jeff Bingaman was born on October 3, 1943. He grew up in the southwestern New Mexico community of Silver City. His father was a chemistry professor and chair of the science department at Western New Mexico University. His mother taught in the public schools. After graduating from Western (now Silver) High School in 1961, Jeff attended Harvard University and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in government in 1965. He then entered Stanford Law School where he met, and later married, fellow law student Anne Kovacovich. Upon earning his law degree from Stanford in 1968, Jeff and Anne returned to New Mexico. They have one son, John. After law school Jeff spent one year as an assistant attorney general and eight years in private law practice in Santa Fe. Jeff was elected Attorney General of New Mexico in 1978 and served four years in that position. In 1982 he was elected to the United States Senate. He was re- elected to a fifth term in the Senate in 2006. At the end of that term he chose not to seek re- election and completed his service in the Senate on January 3, 2013. At the time of his retirement from the Senate he was Chairman of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee. He also served on the Finance Committee, the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee and the Joint Economic Committee. In April of 2013 he began a year as a Distinguished Fellow with the Steyer-Taylor Center for Energy Policy and Finance at Stanford Law School. In the fall of 2015 he taught a seminar on national policy and the Congress in the Honors College at the University of New Mexico. -

THE AMERICAN POWER All- Stars

THE AMERICAN POWER All- Stars Scorecard & Voting Guide History About every two years, when Congress takes up an energy bill, the Big Oil Team and the Clean Energy Team go head to head on the floor of the U.S. Senate -- who will prevail and shape our nation’s energy policy? The final rosters for the two teams are now coming together, re- flecting Senators’ votes on energy and climate legislation. Senators earn their spot on the Big Oil Team by voting to maintain America’s ailing energy policy with its en- trenched big government subsidies for oil companies, lax oversight on safety and the environment for oil drilling, leases and permits for risky sources of oil, and appointments of regulators who have cozy relationships with the industry. Senators get onto the Clean Energy Team by voting for a new energy policy that will move Amer- ica away from our dangerous dependence on oil and other fossil fuels, and toward cleaner, safer sources of energy like wind, solar, geothermal, and sustainable biomass. This new direction holds the opportunity to make American power the energy technology of the future while creating jobs, strengthening our national security, and improving our environment. Introduction Lobbyists representing the two teams’ sponsors storm the halls of the Congress for months ahead of the votes to sway key players to vote for their side. The Big Oil Team’s sponsors, which include BP and the American Petroleum Institute (API), use their colossal spending power to hire sly K-Street lobbyists who make closed-door deals with lawmakers, sweetened with sizable campaign contribu- tions. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Senate Committee Assignments - Democrats

Senate Committee Assignments - Democrats: Agriculture: Banking: Chairwoman Debbie Stabenow Chairman Tim Johnson Patrick Leahy Jack Reed Tom Harkin Charles Schumer Kent Conrad Robert Menendez Max Baucus Daniel Akaka Ben Nelson Sherrod Brown Sherrod Brown Jon Tester Robert Casey Herb Kohl Amy Klobuchar Mark Warner Michael Bennet Jeff Merkley Kirsten Gillibrand Michael Bennet Kay Hagan Appropriations: Chairman Daniel Inouye Commerce: Patrick Leahy Chairman Jay Rockefeller Tom Harkin Daniel Inouye Barbara Mikulski John Kerry Herb Kohl Barbara Boxer Patty Murray Bill Nelson Dianne Feinstein Maria Cantwell Richard Durbin Frank Lautenberg Tim Johnson Mark Pryor Mary Landrieu Claire McCaskill Jack Reed Amy Klobuchar Frank Lautenberg Tom Udall Ben Nelson Mark Warner Mark Pryor Mark Begich Jon Tester Sherrod Brown Energy: Chairman Jeff Bingaman A rmed Services: Ron Wyden Chairman Carl Levin Tim Johnson Joseph Lieberman Mary Landrieu Jack Reed Maria Cantwell Daniel Akaka Bernard Sanders Ben Nelson Debbie Stabenow Jim Webb Mark Udall Claire McCaskill Jeanne Shaheen Mark Udall Al Franken Kay Hagan Joe Manchin Mark Begich Christopher Coons Joe Manchin Jeanne Shaheen Kirsten Gillibrand Richard Blumenthal Environment and Public Works: Health, Education, Labor and Pension: Chairwoman Barbara Boxer Chairman Tom Harkin Max Baucus Barbara Mikulski Thomas Carper Jeff Bingaman Frank Lautenberg Patty Murray Benjamin Cardin Bernard Sanders Bernard Sanders Robert Casey Sheldon Whitehouse Kay Hagan Tom Udall Jeff Merkley Jeff Merkley Al Franken Kirsten Gillibrand -

Congressional Record—Senate S5

January 5, 2011 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S5 administered to them by the Vice scribed to the oath in the Official Oath Mr. REID. Mr. President, I suggest President; and they severally sub- Book. the absence of a quorum. scribed to the oath in the Official Oath The VICE PRESIDENT. Congratula- The VICE PRESIDENT. The absence Book. tions. of a quorum having been suggested, the The VICE PRESIDENT. Congratula- (Applause, Senators rising.) clerk will call the roll. tions. The VICE PRESIDENT. The clerk The legislative clerk proceeded to (Applause, Senators rising.) will read the names of the next four call the roll, and the following Sen- The VICE PRESIDENT. The clerk Senators. ators entered the Chamber and an- will read the names of the next four The legislative clerk called the swered to their names: Senators. names of Mr. MCCAIN, Ms. MIKULSKI, [Quorum No. 1 Leg.] The legislative clerk called the Mr. MORAN, and Ms. MURKOWSKI. Akaka Gillibrand Moran names of Mr. BOOZMAN of Arkansas, These Senators, escorted by Mr. KYL, Alexander Graham Murkowski Mrs. BOXER of California, Mr. BURR of Mr. CARDIN, Mr. SARBANES, Mr. Ayotte Grassley Murray North Carolina, and Mr. COATS of Indi- BROWNBACK, Mr. ROBERTS, Ms. MUR- Barrasso Hagan Nelson (NE) Baucus Harkin Nelson (FL) ana. KOWSKI, and Mrs. Dole, respectively, Bennet Hatch Paul These Senators, escorted by Mr. advanced to the desk of the Vice Presi- Bingaman Hoeven Portman PRYOR, Mr. REID, Mrs. HAGAN, Mr. dent; the oath prescribed by law was Blumenthal Inhofe Pryor Blunt Inouye Reed Faircloth, Mrs. Dole, Mr. Broyhill, Mr. administered to them by the Vice Boozman Isakson Reid LUGAR, and Mr. -

The Relationship Between Nutrition, Aging, and Health: a Personal and Social Challenge

S. HRC. 99-809 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN NUTRITION, AGING, AND HEALTH: A PERSONAL AND SOCIAL CHALLENGE HEARING BEFORE THE SPECIAL COMMTTEE ON AGING UNITED STATES SENATE NINETY-NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ALBUQUERQUE, NM DECEMBER 14, 1985 Serial No. 99-13 Printed for the use of the Special Committee on Aging U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 62-178 0 WASHINGTON 1986 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington. DC 20402 SPECIAL COMMIfTEE ON AGING JOHN HEINZ, Pennsylvania, Chairmnan WILLIAM S. COHEN, Maine JOHN GLENN, Ohio LARRY PRESSLER, South Dakota LAWTON CHILES, Florida CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa JOHN MELCHER, Montana PETE WILSON, California DAVID PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN W. WARNER, Virginia BILL BRADLEY, New Jersey DANIEL J. EVANS, Washington QUENTIN N. BURDICK, North Dakota JEREMIAH DENTON, Alabama CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut DON NICKLES, Oklahoma J. BENNETT JOHNSTON, Louisiana PAULA HAWKINS, Florida JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico STEPHEN R. MCCoNNELL, Staff Director DI&NE LIFsEY, Minority Staff Diretor ROBIN L. KROPF, Chief Clerk (II) CONTENTS Page Opening statement by Senator Jeff Bingaman, presiding ....................................... 1 CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF WITNESSES Blumberg, Jeffrey, Ph.D., acting associate director, Human Nutrition Re- search Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MA . ,,.. ,, 4 Reynolds, Gertrude, Albuquerque, NM, a participant of senior programs through the Office of Aging .15 Lopez, Reynalda, Albuquerque, NM, a participant of programs for seniors through the Office of Senior Affairs in Albuquerque. .18 Keevama, Preston, San Juan Pueblo, NM, chairman, New Mexico Indian Council on Aging .,. ., 19 Candelaria, Susie, Bernalillo, NM, a participant in the Nutrition Program , 21 Lopez, Simon, Las Vegas, NM, member, advisory council, Mora-San Miguel Senior Citizens. -

Puerto Rico Hearing Committee on Energy And

S. HRG. 109–796 PUERTO RICO HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON THE REPORT BY THE PRESIDENT’S TASK FORCE ON PUERTO RICO’S STATUS NOVEMBER 15, 2006 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 33–148 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 07:56 Mar 02, 2007 Jkt 109796 PO 33148 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 P:\DOCS\33148.TXT SENERGY2 PsN: PAULM COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico, Chairman LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska RON WYDEN, Oregon RICHARD M. BURR, North Carolina, TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota MEL MARTINEZ, Florida MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JAMES M. TALENT, Missouri DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CONRAD BURNS, Montana MARIA CANTWELL, Washington GEORGE ALLEN, Virginia KEN SALAZAR, Colorado GORDON SMITH, Oregon ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey JIM BUNNING, Kentucky FRANK MACCHIAROLA, Staff Director JUDITH K. PENSABENE, Chief Counsel BOB SIMON, Democratic Staff Director SAM FOWLER, Democratic Chief Counsel JOSH JOHNSON, Professional Staff Member AL STAYMAN, Democratic Professional Staff Member (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 07:56 Mar 02, 2007 Jkt 109796 PO 33148 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 P:\DOCS\33148.TXT SENERGY2 PsN: PAULM C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Acevedo-Vila´, Hon. -

USSYP 2012 Yearbook

UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGAM THE HEARST FOUNDATIONS DIRECTORS William Randolph Hearst III UNITED STATE President James M. Asher Anissa B. Balson David J. Barrett Frank A. Bennack, Jr. John G. Conomikes S SENATE YO Ronald J. Doerfler Lisa H. Hagerman George R. Hearst, Jr. Harvey L. Lipton Gilbert C. Maurer U Mark F. Miller T H PROGRAM Virginia H. Randt Paul “Dino” Dinovitz EX ECUTIVE DIRECTOR George B. Irish E ASTERN DIRECTOR fifT T I Rayne B. Guilford E P ROGRAM DIRECTOR H UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGRAM ANN I V E R S A R Y W A S H I N G T ON WEEK 2012 SPONSORED BY THE UNITED states senate FUNDED AND ADMINISTERED BY THE HEARST Foundations “ I haVE no other VIEW than to promote the puBLIC THE HEARST Foundations GOOD, and am unamBITIOUS of honors not founded 90 NEW Montgomery STREET · SUITE 1212 · SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105-4504 WWW.USSENATEYOUTH.ORG IN the approBATION of my COUNTRY.” —G GEOR E WASHINGTON Photography by Jakub Mosur Secondary Photography by Erin Lubin Design by Catalone Design Co. UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGAM THE HEARST FOUNDATIONS DIRECTORS William Randolph Hearst III UNITED STATE President James M. Asher Anissa B. Balson David J. Barrett Frank A. Bennack, Jr. John G. Conomikes S SENATE YO Ronald J. Doerfler Lisa H. Hagerman George R. Hearst, Jr. Harvey L. Lipton Gilbert C. Maurer U Mark F. Miller T H PROGRAM Virginia H. Randt Paul “Dino” Dinovitz EX ECUTIVE DIRECTOR George B. Irish E ASTERN DIRECTOR fifT T I Rayne B. Guilford E P ROGRAM DIRECTOR H UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGRAM ANN I V E R S A R Y W A S H I N G T ON WEEK 2012 SPONSORED BY THE UNITED states senate FUNDED AND ADMINISTERED BY THE HEARST Foundations “ I haVE no other VIEW than to promote the puBLIC THE HEARST Foundations GOOD, and am unamBITIOUS of honors not founded 90 NEW Montgomery STREET · SUITE 1212 · SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105-4504 WWW.USSENATEYOUTH.ORG IN the approBATION of my COUNTRY.” —G GEOR E WASHINGTON Photography by Jakub Mosur Secondary Photography by Erin Lubin Design by Catalone Design Co. -

The Energy Challenge We Face and the Strategies We Need the Karl

The Energy Challenge We Face and The Strategies We Need The Karl Taylor Compton Lecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology April 25, 2008 Senator Jeff Bingaman, Chairman Committee on Energy and Natural Resources United States Senate 1 Our nation is the world leader in science, technology and innovation. The students and the faculty here at MIT, both past and present, deserve much of the credit for that leadership. And anyone who pays attention knows that if we, in this country, have something akin to a war room where our energy challenges are being confronted, it is here at MIT. Karl Compton himself said, “nowhere in the country [is there] such a concentration of scientific and engineering laboratories and personnel.” I compliment President Hockfield and all of you who have worked to establish the MIT Energy Initiative, and I thank President Hockfield for her generous invitation and introduction. It is an honor to be here. One of the greatest lessons that I have learned in life is to seek advice from people who know more about a subject than I do. One of those people whose advice I sought before coming here today is former MIT President Chuck Vest, who now serves as President of the National Academy of Engineering. He urged me to say a few words about the factors that have resulted in me—a lawyer and a politician—being so involved and interested in science, technology, and energy policy. The most important factor was probably my father’s lifelong commitment to science. Both my parents were teachers. My mother taught elementary school and my father was the chemistry professor and head of the Science Department at Western New Mexico University in my hometown of Silver City, New Mexico. -

Joint Economic Committee Council of Economic Advisers

JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE (Created pursuant to Sec. 5(a) of Public Law 304, 79th Cong.) CONNIE MACK, Florida, Chairman JIM SAXTON, New Jersey, Vice Chairman SENATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES WILLIAM V. ROTH, Jr. (Delaware) MARK SANFORD (South Carolina) ROBERT F. BENNETT (Utah) JOHN DOOLITTLE (California) ROD GRAMS (Minnesota) TOM CAMPBELL (California) SAM BROWNBACK (Kansas) JOSEPH R. PITTS (Pennsylvania) JEFF SESSIONS (Alabama) PAUL RYAN (Wisconsin) CHARLES S. ROBB (Virginia) PETE STARK (California) PAUL S. SARBANES (Maryland) CAROLYN B. MALONEY (New York) EDWARD M. KENNEDY (Massachusetts) DAVID MINGE (Minnesota) JEFF BINGAMAN (New Mexico) MELVIN L. WATT (North Carolina) SHELLEY S. HYMES, Executive Director COUNCIL OF ECONOMIC ADVISERS MARTIN N. BAILY, Chair ROBERT Z. LAWRENCE, Member [PUBLIC LAW 120Ð81ST CONGRESS; CHAPTER 237Ð1ST SESSION] JOINT RESOLUTION [S.J. Res. 55] To print the monthly publication entitled ``Economic Indicators'' Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the Joint Economic Committee be authorized to issue a monthly publication entitled ``Economic Indicators,'' and that a sufficient quantity be printed to furnish one copy to each Member of Congress; the Secretary and the Sergeant at Arms of the Senate; the Clerk, Sergeant at Arms, and Doorkeeper of the House of Representatives; two copies to the libraries of the Senate and House, and the Congressional Library; seven hundred copies to the Joint Economic Committee; and the required numbers of copies to the Superintendent of Documents for distribution to depository libraries; and that the Superintendent of Documents be authorized to have copies printed for sale to the public. Approved June 23, 1949.