2004 Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Burial Ground AND/OR COMMON

iRev. 10.74 S’I’.Vl’I:S II1’ ICIMLiNI’ UI’ TI lit IN H.RIOR * UNI’i’LI FOR NPS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE RECEIVEQ * NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES I **‘ INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLErENATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES--COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC North Burial Ground AND/OR COMMON LOCATION . STREET& NUMBER Between Branch Avenue and North Main St. FOR PUBLICATION CITY TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT . Providence #1- Rep. Pernand J. St. Germain STATE COOE COUNTY COOS -- Rhode Island 44 Providence 007 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE DtSTRICT ±PU B LI C OCCU PIED _AGRICULTURE -MUSEUM _BUtLDINGISI _,,PRPVATE _UNOCCUPIED COMMERCIAL PAR K ,STRUCTURE _WORIK IN PROGRESS .EDU CAT ID NA L ..PRIVATE RESIDENCE SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE NTE B TA IN M EN T RELPGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED OV E RN ME NT _SCIENTIFIC .BEING CONSIDERED YES’ UNRESTRICTED _INDUSTRIAL _rRANSPORTATION -NO MILITAPY OTHER: cemetery If OWNER OF PROPERTY do Vincent NAME Lanzieri Jr. City of Providence Superintendent, North Burial Ground STREET & NUMBER Branch Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Providence Rhode Island 02904 aL0CATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. r REGISrRY OF DEEDS.ETC Providence City Hall STREEt & NUMBER 25 florrance SttZeet CITY, tOWN - STATE Providence Rhode Island REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS 1-*’ TITLE Providence BroadbruEhj Maunt Hope , -________ L. DATE July 1976 ..FEDERAL XSTAIE COUN[Y DEPOSItORY FOR - SURVEYRECOROS Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission CITYTOWN STATE Providence Rhode p ‘‘ i u’ .. , rC/ ‘ ________ DESCRIPTION ‘ CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE EXCELLENT XDETERIDRATEO UNALTEHED X-ORIGI NAL SITE 000D _RUINS X..ALTERED _MOVED DArE I, _FAIR UNEXP0SED ‘ DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL IF KNOWN PHYSICAL APPEARANCE *. -

Kent Hospital, a Member of Care New England | Rhode Island

BECOMING AN AGE-FRIENDLY HEALTH SYSTEM MEMBERS IN ACTION CASE STUDY Kent Hospital, a member of Care New England | Rhode Island Overview by CNE, South County Health and the Rhode Island Primary Care Physicians Corporation, a multispecialty In February 2019, Kent Hospital, part of Care New independent practice association. England, opened an Adult Care for Elders (ACE) unit to CNE realized to do true population health, it needed to test and implement the Age-Friendly Health Systems meet the needs of its older adults, particularly at Kent 4Ms Framework. The unit focused on documenting Hospital in Warwick, R.I., where the patient volume what matters to the patient and implementing delirium is highest. Since 2014, the health system and Kent screening and prevention plan on all patients. Since leadership teams have supported the growth of a opening, the unit has service line in geriatrics seen a reduction in both and clinical programs length of stay and falls to serve the needs of with injury, along with an older adults across the increase in patient and continuum of care. staff satisfaction. At the start of CNE’s The mission of Care New work to build a service England (CNE) is to be line in geriatric medicine, “your partner in health” a needs assessment and create a community was performed at Kent of healthier people in the Hospital. Admission areas served by the health statistics demonstrated system’s hospitals and that more than 30% of hospital admissions were partners. The 749-bed health system includes five patients over the age of 65, and of that group, most hospitals, a medical group, and a wellness center. -

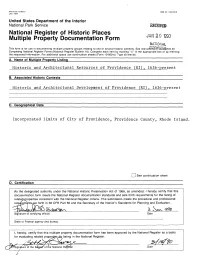

National Register of Historic Places ...On ,Non Multiple Property

NPS Form 10-900-b QMB No 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places .... on ,non Multiple Property Documentation Form JAN ^ J 1b9° NATIONAL This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instrucflSh^R-Gkwiaftnes for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic and Architectural Resources of Providence CRI) > 1656-present B. Associated Historic Contexts Historic and Architectural Development of Providence CRI] , 1656-present C. Geographical Data Incorporated limits of City of Providence, Providence County, Rhode Island LJSee continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of relatecLproperties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requjTrejriefitSfSet forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related propejJ4es/jtco; listing in the National Register. V E. Statement of Historic Contexts Discuss each historic context listed in Section B. -

Bradley Hospital

Community Health Needs Assessment EMMA PENDLETON BRADLEY HOSPITAL SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 a. Description of CHNA Purpose & Goals b. History and Mission of Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital c. Commitment to the Community d. Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital – What it Does II. Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital ‐ Defining the Community it Serves 9 III. Update on 2016 CHNA Implementation Strategy 11 IV. Assessment of Health Needs of the Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital Community 18 V. Identification of the Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital Community’s Significant Needs 25 VI. Conclusion 30 a. Acknowledgements b. Contact Information Appendices 32 References 39 2 I. Introduction A. Description of CHNA Purpose & Goals Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital (EPBH), whose primary location is in East Providence, Rhode Island, is a seventy‐bed non‐profit teaching hospital with university affiliation providing for the psychiatric treatment of adolescents and children, including some with severe developmental disabilities. EPBH operates several major programs including acute, partial hospitalization, residential, and outpatient, as well as The Bradley School through its non‐profit subsidiary, Lifespan School Solutions, Inc. (LSS), which provides special education services to children from preschool through high school. LSS also operates ten other secondary sites which furnish residential and special education services. As a complement to its role in service and education, EPBH actively supports research. EPBH is accredited by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. EPBH participates as a provider in Rhode Island Medicaid, various out‐of‐state Medicaid programs, and the State of Rhode Island’s Department of Children, Youth and Families programs, as well as providing care for patients covered by private health insurers and municipal school departments. -

Medical Journal the Next Hundred

RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL Volume 90 No. 1 January 2007 CENTENNIAL ISSUE Volume 90 No. 1 January 2007 JANUARY 2017 VOLUME 100 • NUMBER 1 ISSN 2327-2228 Biohybrid Limbs A CME Issue CENTENNIAL ISSUE JANUARY 2017 VOLUME 100 • NUMBER 1 ISSN 2327-2228 JANUARY 2017 VOLUME 100 • NUMBER 1 ISSN 2327-2228 Biohybrid Limbs A CME Issue CENTENNIAL EDITION JANUARY 2017 VOLUME 100 • NUMBER 1 ISSN 2327-2228 Increase your Risk IQ Outsmarting risk requires a high degree of intelligence – yours and ours. Changing care delivery models, new technology, and shifting responsibilities create new exposures for physicians and hospitals daily. But with the right risk intelligence, you can predict and prevent those vulnerabilities. Coverys combines proven Medical Professional Liability Insurance with proactive risk analytics, resources, and education to outsmart risk and improve outcomes. Visit Coverys.com or call 800-225-6168 ProSelect Insurance Company RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 5 COMMENTARY Centennial Thoughts JOSEPH H. FRIEDMAN, MD RIMJ Centennial: A personal reminiscence of a 20th-Century nurse MARY KORR 11 aT A GLANCE RIMJ’s Editors of Yesteryear MARY KORR 15 VINTAGE RIMJ Excerpts Depict a Century of Medical Milestones, Maladies and Musings January 1917: News/People, and a Letter to the Editor 19 HOSPITALS IN RI A Chronology of Rhode Island Hospitals Rhode Island’s First Hospitals STANLEY M. ARONSON, MD Butler Hospital: A Tradition of Empathy STANLEY M. ARONSON, MD 27 heritage Crawford Allen Memorial Hospital: Helping Children Heal by the Sea MARY KORR 20th Century Signs of Infectious Times 100 YEARS AGO – JANUary 1917 Commentary Centennial Thoughts JOSEPH H. -

RHODE ISLAND M Edical J Ournal

RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL DR. Montross’ DR. MARTIN BOOK: FALLING ON HOSPICE AND INTO THE FIRE PALLIATIVE CARE PAGE 69 PAGE 49 JACK ELIAS, MD DEAN, ALPERT MEDICAL SCHOOL PAGE 52 SPECIAL SECTION SOCIAL DETERMINANTS of HEALTH JULY 2013 VOLUME 96 • NUMBER 7 ISSN 2327-2228 Some things have changed in 25 years. Some things have not. Since 1988, physicians have trusted us to understand their professional liability, property, and personal insurance needs. Working with multiple insurers allows us to offer you choice and the convenience of one-stop shopping. Call us. rims I B C 800-559-6711 RIMS-INSURANCE BROKERAGE CORPORATION Medical/Professional Liability Property/Casualty Life/Health/Disability RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 14 SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH Our Zip Code May Be More Important Than Our Genetic Code DANNIE RITCHIE, MD, MPH GUEST EDITOR Healthy People 2020 15 Social Determinants of Health: A View on Theory and Measurement FERNANDO DE MAIO, PhD; JOHN MAZZEO, PhD; Alaska Hawaii DANNIE RITCHIE, MD, MPH American Samoa U.S. Virgin Islands Republic of Federated States Marshall Islands of Micronesia Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands Puerto Rico Palau Guam www.healthypeople.gov 20 Social Determinants of Health and the Affordable Care Act DONNA LEONG, BA; LT. GOVERNOR ELIZABETH ROBERTS, BA, MBA 23 Optimizing the Health Impacts of Civil Legal Aid Interventions: The Public Health Framework of Medical-Legal Partnerships ELLEN LAWTON, JD; ELIZABETH TOBIN TYLER, JD 27 Health Impact Assessments EMILY SUTHER, MA; MEGAN SANDEL, MD, MPH 31 Health in All Policies: A Start in Rhode Island DANNIE RITCHIE, MD, MPH; PatRICIA A. -

Appointments

PEOPLE / PLACES Appointments Dr. C. James Sung appointed to leadership roles Heather A. Smith, MD, MPH, in Pathology And Laboratory Medicine at Women reappointed to AMA & Infants, Care New England, Brown legislative Council C. JAMES SUNG, MD, FCAP, has The American Medical Association been appointed chief of pathology Board reappointed HEATHER A. and laboratory medicine at Wom- SMITH, MD, MPH, a member of en & Infants Hospital of Rhode Is- the AMA Foundation Board, to the land, executive chief of pathology Council on Legislation (COL). Her and laboratory medicine at Care new one-year term begins July 1. New England, and vice chair of pa- An obstetrician/gynecologist affil- thology and laboratory medicine at iated with Women and Infants Hospital, she is a graduate of The Warren Alpert Medical School the University of Virginia and the Boston University School of of Brown University. Dr. Sung has Public Health. served as interim chief since 2017. Dr. Smith earned her medical degree at the University of “Dr. Sung has been an integral member of the leadership team Massachusetts Medical School and a certificate of health sci- of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine for 20 ences research at Yale University. She completed a residency in years. For the past two years, he has led the entire department obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital – in an interim role, further stabilizing its operations, and mod- Massachusetts General Hospital and is a graduate of the Robert ernizing and consolidating laboratory service across Care New Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program at Yale. -

CURRICULUM VITAE ANA MARIA ABRANTES, Ph.D. Butler Hospital

8/24/21 CURRICULUM VITAE ANA MARIA ABRANTES, Ph.D. Butler Hospital The Alpert Medical School of Brown University 345 Blackstone Blvd. Providence, RI 02906 401-455-6440 (office) [email protected] EDUCATION 1995 Harvard University, A.B. in Psychology, cum laude 2002 SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology, Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology 2002 Brown University Clinical Psychology Internship Program 2014 Master of Arts, Ad Eundem, Brown University POSTGRADUATE TRAINING 2004 NIAAA T32 Postdoctoral Fellowship, Brown University, Center for Alcohol and Addictions Studies, Providence, Rhode Island HONORS AND AWARDS 1999-2001 Travel Award, Research Society on Alcoholism 2001 APA Division 50 Young Scholar Award 2004 - 2008 Loan Repayment Award for Clinical Research, National Institute on Drug Abuse 2013 Excellence in Reviewing Award, Mental Health and Physical Activity 2016 Society of Behavioral Medicine Leadership Institute Fellow 2016 Education Award, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University PROFESSIONAL LICENSES AND BOARD CERTIFICATION 2007 - Present Psychologist, State of Rhode Island, License# PS01020 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2004 - 2013 Assistant Professor (Research) of Psychiatry and Human Behavior Brown Medical School, Providence, RI 2013 - 2018 Associate Professor (Research) of Psychiatry and Human Behavior Brown Medical School, Providence, RI 2016 - Present Adjunct Faculty, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Brown University 2018 - Present Professor of Psychiatry and Human -

2020 Annual Security Report the Department of Public Safety Provides CONTENTS the Community with the Resources and the Message from the Chief of Police

BROWN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY 2020 Annual Security Report The Department of Public Safety provides CONTENTS the community with the resources and the Message from the Chief of Police . 1 education necessary to make informed choices about their safety . Department personnel Department of Public Safety Staffing, participate in a wide range of campus events Authority, and Jurisdiction . .2 to include University orientations, resource fairs, and other special campus events in an Local and Other Law Enforcement Agencies . .3 effort to provide all members of the community The Clery Act . .3 with valuable and practical safety information . Please visit Public Safety’s website for further Preparing the Annual Security Report . 4 information pertaining to our programs and services . Daily Crime Log . 4. Public Safety website Campus Security Authorities . .5 Reporting Criminal Offenses . .5 24 HOUR EMERGENCY NUMBERS Brown Public Safety/EMS Silent Witness Reporting . .7 On campus: x4111—Off Campus: 401-863-4111 Missing Student Notification Policy . .7 24/7 Sexual Assault Response Line: 401- 863-6000 Emergency Preparedness & Evacuation . .8 Providence Police: 911 or 401- 272-3121 Timely Warning Policy . 9 Day One Sexual Assault and Trauma Center: 800-494-8100 Campus Sex Crimes Prevention Act . 10 Administrator on Call: x4111 (24 hours a day) Sexual and Gender-Based Harassment, Student Support Services: 401- 863-3800 Department of Public Safety: x4111 or x3-3322 Sexual Assault, Interpersonal Violence, Investigations Bureau: 401-863-1663 and Stalking Policy . 10 TITLE IX RESOURCES Understanding Public Safety’s Response to Sexual Assault . .12 FOR STUDENTS, FACULTY AND STAFF Student Violations of the Code of Student Conduct . -

Celebration of Excellence in Hospital Care

The 27th Annual Celebration of Excellence in Hospital Care March 15, 2017 Hospital Association of Rhode Island 5:30 p.m. Reception 405 Promenade Street, Ste. C Providence, Rhode Island 02908 6:30 p.m. Awards Ceremony p 401-443-2803 / f 401-533-9328 www.HARI.org Crowne Plaza, Warwick, RI HARI Affiliate Members Aetna Applied Management Systems AstraZeneca Merritt Hawkins Rhode Island College Truven Health HARI Member Hospitals Welcome to the 27th Annual Celebration of Excellence in Hospital Care. Butler Hospital Kent Hospital Tonight is a recognition of the heroes in our hospitals - employees who go above and beyond each day to ensure Fatima Hospital superior patient care. Landmark Medical Center We will also present the Edward J. Quinlan Award Memorial Hospital of RI for Patient Safety Excellence. Providence VA Medical Center The awards ceremony will commence at 6:30 p.m. Roger Williams Medical Center Enjoy the evening! South County Hospital Westerly Hospital Women & Infants Hospital Butler Hospital Edward J. Quinlan Award for Patient Safety Excellence Micaela Condon, Patient Assessment Services Clinician The Edward J. Quinlan Award for Patient Safety Excellence honors Micaela began her career in 2006 as a mental health worker/ a hospital unit and/or team that has implemented an initiative that has achieved measurable results in improving quality and patient safety. CNA at Butler Hospital. In 2010, she pursued her master’s degree in social work at Rhode Island College. Upon graduation, she transitioned to care planner and gained experience in Butler’s Young Adult Partial Hospital Program. After more than a decade of service, Micaela now works as a member of the multidisci- plinary team of the newly opened Hall @ Center House. -

Hclassifi Cation

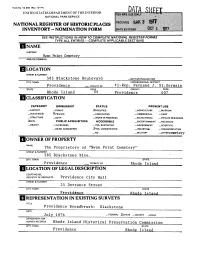

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES ...... INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Swan Point Cemetery AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 585 Blackstone Boulevard _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Providence _.VICINITY OF #l-Rep. Fernand J. St.Germain STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Rhode Island 44 Providence 007 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC JXOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE -XsiTE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY ~OTHER cemetery OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME The Proprietors of "Swan Point Cemetery" CITY. TOWN STATE Providence VICINITY OF Rhode Island LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Providence City Hall STREET& NUMBER 25 Dorrance Street CITY, TOWN STATE Providence Rhode Island REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Providence Broadbrush: Blackstone DATE July 1976 -FEDERAL X.STATE COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEYRECORDS Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission CITY, TOWN STATE Providence Rhode Island DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE XEXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED .X.ORIGINALSITE _GQOD —RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED Swan Point Cemetery, located in the northeast corner of Providence, is bounded on the west by Blackstone Boulevard, on the south by Butler Hospital, on the east by the Seekonk River, and on the north by the City of Pawtucket and Riverside Cemetery. -

February 13, 2007

Ana Tuya Fulton, MD November 3, 2020 Curriculum Vitae Ana Tuya Fulton, MD, MBA, FACP, AGSF (Ana Cristina Tuya, MD) PERSONAL INFORMATION Business Address: Kent Hospital 455 Tollgate Road Warwick RI 02886 Business Phone: 401-736-4287 Business Fax: 401-736-1071 Business Email: [email protected] or [email protected] EDUCATION Undergraduate 1993-1997 The George Washington University Washington DC. Major in Psychology, BA. Graduation Summa Cum Laude Early Acceptance to The George Washington University School of Medicine. Medical School 1997-2001 The George Washington University School of Medicine Washington DC. Awarded MD and graduated with distinction on May 20, 2001. Graduate 2/2020-11/2020 Masters of Business Administration, Healthcare Management Western Governor’s University POSTGRADUATE TRAINING Residency 2001-2004 Brown University, Rhode Island Hospital, Rhode Island. Internal Medicine 2001-2004 PGY 1-3. 593 Eddy Street JB 0100 Providence RI 02903. Chief Residency 2004-2005 Brown University, Rhode Island Hospital. PGY 4 Internal Medicine. Fellowship 2005-2006 Brown University, Rhode Island Hospital, Division of Geriatrics. Geriatric Medicine Fellowship 2007-2008 Brown University Harriet W. Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning – Certificate I POSTGRADUATE HONORS AND AWARDS 2005 Haffenreffer Fellow in Medical Sciences in the Internal Medicine Program. Awarded for work done chief residency year 7/2004- 6/2005 1 Ana Tuya Fulton, MD 2006 Chosen as Futures Program Participant for the 2006 American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) Annual Meeting 2007 Geriatric Academic Career Award (GACA) from HRSA awarded Three year funding for academic geriatricians. 2011 Recommended for Invited Fellowship to American College of Physicians. Elected a Fellow of the College March 1, 2011 2016 John A.