Sleep-Wake Complaints and Their Relation to Sleep Disturbance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physiological and Pharmacological Factors of Insomnia in HIV Disease

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Nursing Nursing January 1999 Physiological and pharmacological factors of insomnia in HIV disease Kenneth D. Phillips University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nurspubs Part of the Critical Care Nursing Commons Recommended Citation Phillips, K. D. (1999). Physiological and pharmacological factors of insomnia in HIV disease. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 10(5), 93-97. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nursing at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Nursing by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clinical Column JANACPhillips /Vol. Insomnia 10, No. and 5, September/OctoberHIV Disease 1999 Physiological and Pharmacological Factors of Insomnia in HIV Disease Kenneth D. Phillips, PhD, RN For almost two decades, HIV infection has been a Ungvarski, 1995), and the side effects of many antiret- progressive disease leading to early morbidity and roviral therapies and other drugs (Chohan, 1999) used mortality for more than a million Americans (Centers to treat HIV disease may produce insomnia. Although for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1998). helping the client manage sleep disturbance is of great Although HIV infection strikes people of any age, it importance, available information in this area remains continues to be a disease of young persons in relatively modest. good health. Persons with HIV (PWHIV) who are in Insomnia frequently begins prior to the diagnosis of the advanced stages of the disease typically experience HIV,and it continues throughout the disease (Norman, very troubling symptoms. -

Daytime Sleepiness

Med Lav 2017; 108, 4: 260-266 DOI: 10.23749/mdl.v108i4.6497 Daytime sleepiness: more than just Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) Luigi Ferini-Strambi, Marco Sforza, Mattia Poletti, Federica Giarrusso, Andrea Galbiati IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Milan, Italy KEY WORDS: Daytime sleepiness; Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA); hypersomnia PAROLE CHIAVE: Sonnolenza diurna; Apnee Ostruttive del Sonno (OSA); ipersonnia SUMMARY Excessive Daytime Sleepiness (EDS) is a common condition with a significant impact on quality of life and general health. A mild form of sleepiness can be associated with reduced reactivity and modest distractibility symptoms, but more severe symptomatic forms are characterized by an overwhelming and uncontrollable need to sleep, causing sud- den sleep attacks, amnesia and automatic behaviors. The prevalence in the general population is between 10 and 25%. Furthermore, EDS has been considered a core symptom of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), as well as being the main symptom of primary hypersomnias such as narcolepsy types 1 and 2, and idiopathic hypersomnia. Moreover, it can be considered secondary to other sleep disorders (Restless Legs Syndrome, Chronic insomnia, Periodic Limb Movements), psychiatric conditions (Depression, Bipolar Disorder) or a consequence of the intake/abuse of drugs and/or substances. An accurate medical history cannot be sufficient for the differential diagnosis, therefore instrumental recordings by means of polysomnography and the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) are mandatory for a correct diagnosis and treatment of the underlying cause of EDS. RIASSUNTO «Sonnolenza diurna: più di una semplice Apnea Ostruttiva nel Sonno (OSA)». L’eccessiva sonnolenza diurna (Excessive Daytime Sleepiness, EDS) è una condizione molto comune con un impatto significativo sulla qualità di vita e sulla salute in generale. -

Case Report and Review of Literature on Hypersomnia As a Result of Stroke Pradeep C

ISSN: 2638-1583 Madridge Journal of Neuroscience Case Report Open Access Sleepiness after Stroke: Case Report and Review of Literature on Hypersomnia as a Result of Stroke Pradeep C. Bollu1, Ashutosh Pandey2, Siva Prasad Pesala3 and Krishna Nalleballe1* 1Assistant Professor, Department of Neurology, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA 2Albert Einstein School of Medicine, Bronx NY, USA 3Neurologist, Department of Neurology, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA Article Info Keywords: Hypersomnia; Stroke; Daytime sleepiness; Conventional angiogram. *Corresponding author: Abbreviations: MRA: Magnetic resonance angiography; MRI: Magnetic resonance Krishna Nalleballe imaging; PLMS: Periodic limb movements in sleep; NREM: Non rapid eye movement; Assistant Professor SDB: Sleep disordered breathing Department of Neurology University of Missouri, Columbia 65212, USA Introduction Tel. 6032897308/5738821515 E-mail: [email protected] Daytime sleepiness is defined as the inability to stay awake and alert during the major waking episode of the day resulting in irrepressible need for sleep or unintended Received: March 16, 2017 lapses into drowsiness. Excessive sleepiness affects up to 5% of the general population Accepted: March 23, 2017 and can result in significant disability. Hypersomnia can be either the result of unmet Published: March 28, 2017 sleep needs or can also be due to reduced activity of alerting systems in the brain. The Citation: Bollu CP, Pandey A, Pesala SP, former can be due to sleep restriction or from sleep disruption. The International Nalleballe K. Sleepiness after Stroke: Case Classification of Sleep disorders categorize various disorders of hyper somnolence into Report and Review of Literature on Hypersomnia different sub-groups. Exaggerated sleep propensity with daytime sleepiness and/ or as a Result of Stroke. -

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Enhances Depression Outcome in Patients with Comorbid Major Depressive Disorder and Insomnia

INSOMNIA AND DEPRESSION Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Enhances Depression Outcome in Patients with Comorbid Major Depressive Disorder and Insomnia Rachel Manber, PhD1; Jack D. Edinger, PhD2; Jenna L. Gress, BA1; Melanie G. San Pedro-Salcedo, MA1; Tracy F. Kuo, PhD1; Tasha Kalista, MA1 1Stanford University, Stanford, CA; 2VA Medical Center and Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC Study Objective: Insomnia impacts the course of major depressive severity index (ISI), daily sleep diaries, and actigraphy. disorder (MDD), hinders response to treatment, and increases risk for EsCIT + CBTI resulted in a higher rate of remission of depression depressive relapse. This study is an initial evaluation of adding cogni- (61.5%) than EsCIT + CTRL (33.3%). EsCIT + CBTI was also associat- tive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) to the antidepressant medi- ed with a greater remission from insomnia (50.0%) than EsCIT + CTRL cation escitalopram (EsCIT) in individuals with both disorders. (7.7%) and larger improvement in all diary and actigraphy measures of Design and setting: A randomized, controlled, pilot study in a single sleep, except for total sleep time. academic medical center. Conclusion: This pilot study provides evidence that augmenting an Participants: 30 individuals (61% female, mean age 35±18) with MDD antidepressant medication with a brief, symptom focused, cognitive- and insomnia. behavioral therapy for insomnia is promising for individuals with MDD Interventions: EsCIT and 7 individual therapy sessions of CBTI or and comorbid insomnia in terms of alleviating both depression and in- CTRL (quasi-desensitization). somnia. Measurements and results: Depression was assessed with the Keywords: Major depressive disorder, Insomnia, Cognitive behavioral HRSD17 and the depression portion of the SCID, administered by raters therapy, Remission masked to treatment assignment, at baseline and after 2, 4, 6, 8, and Citation: Manber R; Edinger JD; Gress JL; San Pedro-Salcedo MG; 12 weeks of treatment. -

Periodic Hypersomnia, Congenital Ectodermal Disorders and Multiple Exostosis

PERIODIC HYPERSOMNIA, CONGENITAL ECTODERMAL DISORDERS AND MULTIPLE EXOSTOSIS RUBENS REIMÃO * — ARON DIAMENT ** SUMMARY — A case of periodic hypersomnia in an 11-year-old female with the unique features of mental deficiency, incontinentia pigmenti, acanthosis nigricans and hereditary multiple exostosis (diaphysial aclasis) is reported. The clinical, Polysomnographic and Multiple Sleep Latency test features of this case with a follow up of seven years are consistent with a diagnosis of periodic (intermittent) excessive somnolence. The unique presentation, however, does differ from Kleine-Levin syndrome and suggests a relationship between the predominantly ectodermal, congenital disorders and the sleep-wake, pattern dysfunction. Hipersônia periódica, malformações ectodérmicas e exostose múltipla. RESUMO — Relata-se um caso de sonolência excessiva periódica acompanhada de hiperfagia, com início na segunda década, documentado clinicamente, em tragados polissonográficos de noite inteira e no teste das Latências Múltiplas do Sono. Apresenta características que o distinguem da síndrome de Kleine-Levin, a saber, a ocorrência no sexo feminino, deficiência mental, incontinência pigmentar, acantose nigricans e exostose múltipla. There are two well defined syndromes of periodic hypersomnia!: menstrual cycle-related somnolence and the Kleine-Levin syndrome (KLS). The former is usually temporally linked with the menses; the latter, a rare condition, is generally limited to males in which the first episode of excessive sleepiness occurs in the second decade of life associated with hyperphagia. It supposedly results from hypothalamic or lymbic dysfunctions. This report describes a case of periodic hypersomnia and hyperphagia, beginning in the second decade but clearly distinct from KLS, occurring in a female with mental deficiency, incontinentia pigmenti and multiple exostosis. -

Excessive Daytime Sleepiness and Unintended Sleep Episodes

review article Oman Medical Journal [2015], Vol. 30, No. 1: 3–10 Excessive Daytime Sleepiness and Unintended Sleep Episodes Associated with Parkinson’s Disease Fatai Salawu1* and Abdulfatai Olokoba2 1Department of Medicine, Federal Medical Centre, Yola, Nigeria 2Department of General Internal Medicine, University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin. Nigeria ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: This article looks at the issues of excessive daytime sleepiness and unintended sleep Received: 31 December 2012 episodes in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and explores the reasons why patients Accepted: 7 December 2014 might suffer from these symptoms, and what steps could be taken to manage them. During the last decade, understanding of sleep/wake regulation has increased. Several brainstem Online: nuclei and their communication pathways in the ascending arousing system through the DOI 10.5001/omj.2015.02 hypothalamus and thalamus to the cortex play key roles in sleep disorders. Insomnia is Keywords: the most common sleep disorder in PD patients, and excessive daytime sleepiness is also Parkinson Disease; Sleep; common. Excessive daytime sleepiness affects up to 50% of PD patients and a growing Dopamine Agonists; body of research has established this sleep disturbance as a marker of preclinical and Pedunculopontine Nucleus. premotor PD. It is a frequent and highly persistent feature in PD, with multifactorial underlying pathophysiology. Both age and disease-related disturbances of sleep-wake regulation contribute to hypersomnia in PD. Treatment with dopamine agonists also contribute to excessive daytime sleepiness. Effective management of sleep disturbances and excessive daytime sleepiness can greatly improve the quality of life for patients with PD. -

Original Articles

ORIGINAL ARTICLES Improvement in Cataplexy and Daytime Somnolence in Narcoleptic Patients with Venlafaxine XR Administration Rafael J. Salin-Pascual, M.D., Ph.D. Narcoleptic patients have been treated with stimulants for sleep attacks as well as day- time somnolence, without effects on cataplexy, while this symptoms has been treated with antidepressants, that do not improve daytime somnolence or sleep attacks. Venlafaxine inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine, serotonin, and to lesser extent dopamine, and also suppressed REM sleep. Because some of the symptoms of nar- colepsy may be related to REM sleep deregulation, venlafaxine was studied in this sleep disorder. Six narcoleptic patients were studied, they were drug-free and all of them had daytime somnolence and cataplexy attacks. They underwent the following sleep proce- dure: one acclimatization night, one baseline night, followed by multiple sleep latency test. After two days of the sleep protocol, patients received 150 mg of venlafaxine XR at 08:00 h. Two venlafaxine sleep nights recordings were performed. Patients were fol- lowed for two months with weekly visits for clinical evaluation. Sleep log and analog- visual scale for alertness and somnolence were performed on each visit. Venlafaxine XR was increase by the end of the first month to 300 mg/day. Sleep recordings showed that during venlafaxine XR two days acute administration the following findings: increase in wake time and sleep stage 1, while REM sleep time was reduced. No changes were observed in the rest of sleep architecture variables. Cataplexy attacks were reduced since the first week of venlafaxine administration. Daytime somnolence was reduced also, but until the 7th week and with 300 mg/day of venlafaxine XR administration. -

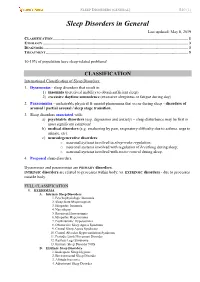

Sleep Disorders in General Last Updated: May 8, 2019 CLASSIFICATION

SLEEP DISORDERS (GENERAL) S40 (1) Sleep Disorders in General Last updated: May 8, 2019 CLASSIFICATION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 ETIOLOGY ................................................................................................................................................ 3 DIAGNOSIS................................................................................................................................................ 3 TREATMENT ............................................................................................................................................. 5 10-15% of population have sleep-related problems! CLASSIFICATION International Classification of Sleep Disorders: 1. Dyssomnias - sleep disorders that result in: 1) insomnia (perceived inability to obtain sufficient sleep) 2) excessive daytime somnolence (excessive sleepiness or fatigue during day) 2. Parasomnias - undesirable physical & mental phenomena that occur during sleep - disorders of arousal / partial arousal / sleep stage transition. 3. Sleep disorders associated with: a) psychiatric disorders (esp. depression and anxiety) – sleep disturbance may be first or most significant symptom! b) medical disorders (e.g. awakening by pain, respiratory difficulty due to asthma, urge to urinate, etc). c) neurodegenerative disorders: o neuronal systems involved in sleep-wake regulation; o neuronal systems involved with regulation of breathing during -

Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Patients with Myasthenia Gravis

Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 2 (2015) 93–97 93 DOI 10.3233/JND-140057 IOS Press Research Report Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Patients with Myasthenia Gravis C.D. Kassardjiana, S. Kokokyib, C. Barnetta,b, D. Jewellc, V. Brila,b, B.J. Murraya,c and H.D. Katzberga,b,∗ aDivision of Neurology, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada bUniversity Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada cSunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada Abstract. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) has not been investigated using objective tests in myasthenia gravis (MG). We investigated whether objective measurements of somnolence better detected abnormalities compared with sleepiness question- naires in MG, and determine if MG patients have EDS. Eight patients with mild-to-moderate MG were recruited. Patients completed maintenance of wakefulness, overnight polysomnography, multiple sleep latency tests, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and fatigue questionnaires. Seven patients demonstrated EDS on objective testing, while Epworth scores were abnormal in two, and the measures showed poor correlation. Our findings highlight that the ESS may be inadequate to diagnose EDS and lead to under-reporting of daytime somnolence in patients with MG. Keywords: Myasthenia gravis, sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep apnea INTRODUCTION There are no studies quantifying increased sleep tendency in MG using objective measures in a sleep Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder laboratory. The aim of this study was to investigate of the neuromuscular junction characterized by fati- whether objective measurements of increased sleep gable weakness. Patients with MG often complain of tendency correlate with subjective sleepiness question- non-restful sleep and daytime somnolence. Studies of naires, and reliably detect somnolence in MG. -

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Complete Database Searches

Manuscript title: A systematic review of instruments for the assessment of insomnia and sleep hygiene practices among adults SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Complete database searches: 1. PubMed (1966-April 2018) Date Results Limitations Results after Combination of terms used limitation 28/3 (sleep disorders AND 3786 Observational studies, 99 insomnia*) AND (Instrument validation studies OR questionnaire OR measure human studies OR scale) English Arabic Adults (19-65+) 28/3 (Insomnia OR sleep 6387 Validation studies 148 deprivation) AND (Instrument Observational studies OR subjective measure OR Human questionnaire) English Arabic Adults (19-65+) 7/4 (sleep quality OR dyssomnias 23529 Validation studies 394 OR daytime sleepiness) AND Human (instrument OR questionnaire English OR scale) Arabic Adults (19-65+) (Sleep hygiene OR sleep 3258 Validation studies 40 7/4 habits OR sleep practices) Observational studies AND (Instrument OR Human questionnaire OR measure*) English Arabic Adults (19-65+) (("sleep arousal disorders" OR 15989 Validation studies 135 28/3 "sleep disturbance") AND Human insomnia* OR sleepiness) English Manuscript title: A systematic review of instruments for the assessment of insomnia and sleep hygiene practices among adults AND (Instrument OR Arabic questionnaire OR scale OR Adults (19-65+) measure) ("sleep efficiency" OR "sleep 1480 Validation studies 41 7/4 dissatisfaction") AND Observational studies (Instrument OR questionnaire Human OR scale OR measure) English Arabic Adults (19-65+) 7("sleep disorders" OR " sleep 451 No study limits 320 7quality" OR " sleep deprivation" 7/4 / OR "sleepiness" OR " Human 4insomnia" OR "sleep English / dysfunction" OR "dyssomnias" Arabic 4OR "sleep arousal disorders") Adults (19-65+) 2AND (instrument OR tool OR 9scale OR questionnaire OR survey OR "patient-reported outcomes") AND ("validation studies" OR "psychometric properties") Total number of articles = 1,197 Manuscript title: A systematic review of instruments for the assessment of insomnia and sleep hygiene practices among adults 2. -

Drug-Induced Sleepiness and Insomnia: an Update Sonolência E Insônia Causadas Por Drogas: Artigo De Atualização

36 Drug-induced sleepiness UPDATE ARTICLE Drug-induced sleepiness and insomnia: an update Sonolência e insônia causadas por drogas: artigo de atualização Renato Gonçalves1, Sonia Maria Guimarães Togeiro2 ABSTRACT doctor’s task is more complex as more comorbid conditions are Medical practice of sleep medicine requires an extensive found in these patients, which makes patient evaluation more pharmacological knowledge, especially when you need to make difficult and intriguing. decisions about the drug scheme already adopted by a given In this update, we focus on the potential for sedation patient. The care of patients with multiple diseases and using of or insomnia of drugs used in the most common chronic multiple drugs has become common. The great challenge facing the physician is to what extent one or more drugs may be contributing diseases worldwide. Doctors often treat patients with multiple to the complaint of sleepiness or insomnia. Any drug with activity comorbidities. It is estimated that 25% of the population of in the central nervous system has the potential to affect sleep-wake North America presents more than one chronic disease(1). cycle. The pharmacokinetic drug knowledge’s will be useful in Among the more prevalent chronic diseases across the world are determining the likelihood of adverse effects on sleep-wake functioning. In this article we describe the potential sedative or in cardiovascular diseases (systemic hypertension, congestive heart generating insomnia by drugs used in the major chronic diseases in failure, and coronary insufficiency), diabetes mellitus, chronic the population. obstructive pulmonary diseases, arthritis, depression, and cere- Keywords: conscious sedation, drugs, hypersomnia, sleep, sleep brovascular accident(2). -

Idiopathic-Hypersomnia-.Pdf

Research & Reviews: Neuroscience Idiopathic Hypersomnia Diksha Gupta1* and Trisha Chatterjee2 1Amity Institute of Pharmacy, Amity University, India 2Department of Biotechnology, Amity University, India Review Article Received date: 08/11/2016 ABSTRACT Accepted date: 27/01/2017 Sleep is an unconsciousness form by which the person Published date: 06/02/2017 could be aroused by sensory or other stimuli. These days due to psychological and social dysfunction our daily routine affects the *For Correspondence quality of our life, according to survey much health related issues are being reported due to lack of sleep. An ancient literature Gupta D, Amity University, Noida, UP, India, Tel: review was given and explained the theory about the leading 8588829759. symptom of idiopathic hypersomnia was sleep drunkenness and the first patient was thus diagnosed with prolonged nocturnal E-mail: [email protected] sleep accompanied by excessive daytime sleepiness with long naps and difficult awakening. A severe issue with this disease is Keywords: Idiopathic hypersomnia, Lengthy that most people tend to suffer from "Depression". Due to ischemic sleep, Narcolepsy, Obstructive sleep changes along the border of mesencephalon and diencephalon and post-traumatic etiology in other, people thus suffer from "sleep apnea, Narcolepsy, Bruxism, Non-rapid eye drunkenness". The term idiopathic hypersomnia was given a variety movement, Hypersomnia of clinical labels including idiopathic central nervous hypersomnia or hypersomnolence, functional hypersomnia, mixed or harmonious hypersomnia, hypersomnia with automatic behavior, and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) narcolepsy. Two different clinical forms were recommended —idiopathic hypersomnia with long sleep time and IH without long sleep time which then reappeared in the latest International Classification of Sleep Disorders.