Downloaded from Genbank Were Corrected Following Criteria Detailed Hereunder, Urging the Need of Following a Standardised Protocol to Annotate Mitogenome Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd / Species Recruitment and Succession on Coastal Defence

The influence of engineering design considerations on species recruitment and succession on coastal defence structures by Juliette Jackson, Plymouth University A thesis submitted to Plymouth University in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Marine Biology and Ecology Research Centre School of Marine Science and Engineering December 2014 I II This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. III IV AUTHOR'S DECLARATION At no time during the registration for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has the author been registered for any other University award. Work submitted for this research degree at the Plymouth University has not formed part of any other degree. Relevant scientific seminars and conferences were regularly attended at which work was often presented; external institutions were visited to forge collaborations and a contribution to two collaborative papers made, which have been published. Further papers with the author of this thesis as first author are in preparation for publication. Publications: Firth, L. B., R. C. Thompson, M. Abbiati, L. Airoldi, K. Bohn, T. J. Bouma, F. Bozzeda, V. U. Ceccherelli, M. A. Colangelo, A. Evans, F. Ferrario, M. E. Hanley, H. Hinz, S. P. G. Hoggart, J. Jackson, P. Moore, E. H. Morgan, S. Perkol-Finkel, M. W. Skov, E. M. Strain, J. van Belzen, S. J. Hawkins (2014). “Between a rock and a hard place: environmental and engineering considerations when designing flood defence structures” Coastal Engineering 87: 122 – 135 Firth L.B., Thompson, R.T., White, F.J., Schofield, M., Skov, M.W., Hoggart, S.P.G., Jackson, J., Knights, A.M. -

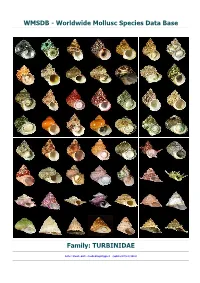

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

2020 Annual Report

EMBRC: 2020 annual report Marine biodiversity is becoming an increasing concern with climate change and marine pollution, and, as a result, is of high relevance in the forthcoming UN Decade of the Ocean and Europe’s Green Deal. One of EMBRC’s principal activities is the provision of access to marine biodiversity, in all its forms. EMBRC Operators include some of the oldest marine institutes in the world and operate long-term observations, host biodiversity monitoring activities, and conduct research. In order to provide holistic information on biodiversity composition at these sites, EMBRC will establish EMO BON, a coordinated European Marine Omics Biodiversity Observation Network across its partners. This will constitute a new approach for EMBRC, and a step in a new direction, toward data generation and long-term observation. EMO BON presents an important need for the EMBRC user community and the opportunity to start filling the void in biological observation that we currently face in regard to physical and chemical observation. This is also an exciting opportunity to generate data for the marine microbiome studies currently in progress, and support Atlantic strategies, such as the Atlantic Ocean Research Alliance (AORA). Knowledge-based management of our blue planet is only possible by unified global monitoring using comparable data, which, in the case of biodiversity, cannot currently be assessed by remote sensing. In this context, EMBRC wishes to contribute to the global coordination of marine biodiversity by –omics approaches, integrating forthcoming technologies as appropriate. We aim to reach and interact with other relevant initiatives, offering the advantages of a sustainable RI that can support active research and underpin the development and optimisation of new methods. -

Complex Male Mate Choice in Marine Snails Littorina

Complex Male Mate Choice in Marine Snails Littorina Sara Hintz Saltin Licentiate thesis Department of Marine Ecology University of Gothenburg Till Mamma, Pappa och Hanna Abstract The ability to recognise potential mates and choose the best possible mating-partner is of fundamental importance for most animal species. This thesis presents studies of male mate choice within the genus Littorina. Males of this genus are sometimes observed to initiate mating with other males or with females of other species. How such suboptimal mating patterns can evolve is the theme of this thesis. In one study we investigated pre-copulatory- and copulation behaviour in L. fabalis and between this species and its sister-species L. obtusata. We found that males preferred to mount and mate with large and more fecund females rather than small females. Males also preferred to track the largest females mucus trails even though these were trails from another species (L. obtusata) although cross-matings were interrupted before completion. In a second study we found that males of three species (L. littorea, L. fabalis and L. obtusata) preferentially followed female trails. This suggests that females add a “gender cue” in the mucus. In the forth species, L. saxatilis, males followed male and female trails at random. Along with experimental evidence for high mating costs and abilities for male L. saxatilis to detect females of a related species, this suggests a sexual conflict over mating frequency. To reduce number of matings females avoid advertising their sex by disguise their mucus. The reason for the different species strategies is that L. -

The Causal Relationship Between Sexual Selection and Sexual Size Dimorphism in Marine Gastropods

Title Document The causal relationship between sexual selection and sexual size dimorphism in marine gastropods Terence P. T. Ng1,a, Emilio Rolán-Alvarez2,3,a, Sara Saltin Dahlén4, Mark S. Davies5, Daniel Estévez2, Richard Stafford6, Gray A. Williams1* 1 The Swire Institute of Marine Science and School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China 2 Departamento de Bioquímica, Genética e Inmunología, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de Vigo, 36310 Vigo Spain 3 Centro de Investigación Mariña da Universidade de Vigo 4 Department of Marine Sciences - Tjärnö, University of Gothenburg, SE-452 96 Strömstad, Sweden 5 Faculty of Applied Sciences, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, U.K. 6 Faculty of Science and Technology, Bournemouth University, U.K. a Contributed equally to this work *Correspondence: Gray A. Williams, The Swire Institute of Marine Science, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: (852) 2809 2551 Fax: (852) 2809 2197 Author contribution. TPTN obtained data from all species except L. fabalis and contributed to data analysis, SHS contributed to sampling Swedish littorinids, MSD, RS and GAW to sampling HK littorinids, DE to Spanish samples, and ER-A contributed to Spanish sampling and data analysis. Developing the MS was led by TPTN, ER-A and GAW and all authors contributed to writing the MS and gave final approval for submission. Competing interests. We declare we have no competing interests. Acknowledgements. Permission to work at the Cape d' Aguilar Marine Reserve was granted by the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department of the Hong Kong SAR Government (Permit No.: (116) in AF GR MPA 01/5/2 Pt.12). -

Comparative Characterization of the Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of the Three Apple Snails (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae) and the Phylogenetic Analyses

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Comparative Characterization of the Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of the Three Apple Snails (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae) and the Phylogenetic Analyses Huirong Yang 1,2, Jia-en Zhang 3,*, Jun Xia 2,4 , Jinzeng Yang 2 , Jing Guo 3,5, Zhixin Deng 3,5 and Mingzhu Luo 3,5 1 College of Marine Sciences, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510640, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Human Nutrition, Food and Animal Sciences, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA; [email protected] (J.X.); [email protected] (J.X.) 3 Institute of Tropical and Subtropical Ecology, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China; [email protected] (J.G.); [email protected] (Z.D.); [email protected] (M.L.) 4 Xinjiang Acadamy of Animal Sciences, Institute of Veterinary Medicine (Research Center of Animal Clinical), Urumqi 830000, China 5 Guangdong Engineering Research Center for Modern Eco-Agriculture and Circular Agriculture, Guangzhou 510642, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-20-85285505; Fax: +86-20-85285505 Received: 11 October 2018; Accepted: 2 November 2018; Published: 19 November 2018 Abstract: The apple snails Pomacea canaliculata, Pomacea diffusa and Pomacea maculate (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda: Ampullariidae) are invasive pests causing massive economic losses and ecological damage. We sequenced and characterized the complete mitochondrial genomes of these snails to conduct phylogenetic analyses based on comparisons with the mitochondrial protein coding sequences of 47 Caenogastropoda species. The gene arrangements, distribution and content were canonically identical and consistent with typical Mollusca except for the tRNA-Gln absent in P. diffusa. -

English Universities Press LTD, XII + 323P., Londres, 1964

ISSN 0374-5686 e-ISSN 2526-7639 http://dx.doi.org/10.32360/acmar.v51i1.19718Cristiane Xerez Barroso, Soraya Guimarães Rabay, Helena Matthews-Cascon Arquivos de Ciências do Mar MOLLUSKS ON RECRUITMENT PANELS PLACED IN AN OFFSHORE HARBOR IN TROPICAL NORTHEASTERN BRAZIL Moluscos associados a placas de recrutamento instaladas em um porto offshore no Nordeste Tropical Brasileiro Cristiane Xerez Barroso1, Soraya Guimarães Rabay2, Helena Matthews-Cascon3 1 Instituto de Ciências do Mar, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Av. Abolição, 3207, Meireles, Fortaleza, CEP 60.165-08, CE, Brasil, Bolsista de Pós-Doutorado PNPD-CAPES, e-mail: [email protected]. 2 Laboratório de Invertebrados Marinhos, Departamento de Biologia, Centro de Ciências, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Campus do Pici, Bloco 909, CEP 60455-760, Fortaleza, CE, Brasil; e-mail: [email protected]. 3 Laboratório de Invertebrados Marinhos, Departamento de Biologia, Centro de Ciências, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Campus do Pici, Bloco 909, CEP 60455-760, Fortaleza, CE, Brasil; e-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT In order to contribute to knowledge of marine fouling communities, the present study analyzed the temporal variation in molluscan communities found on quarterly and annual recruitment panels placed in a seaport area of northeastern Brazil. A set of 30 artificial panels was submerged among pier pillars to a depth of approximately 6 m. Every three months, one subset of 15 panels was removed to examine the biota present. The second subset of 15 panels was left submerged for one year, and then removed for analysis. On the same day that the panels were removed, they were replaced with new panels. -

Atlantic Area Eunis Habitats Adding New Habitat Types from European Atlantic Coast to the EUNIS Habitat Classification

Atlantic Area Eunis Habitats Adding new habitat types from European Atlantic coast to the EUNIS Habitat Classification MeshAtlantic Technical Report Nº 3/2013 September 2013 Atlantic Area Eunis Habitats Adding new habitat types from European Atlantic coast to the EUNIS Habitat Classification MeshAtlantic Technical Report Nº 3/2013 September 2013 Citation: Monteiro, P., Bentes, L., Oliveira, F., Afonso, C., Rangel, M., Alonso, C., Mentxaka, I., Germán Rodríguez, J., Galparsoro, I., Borja, A., Chacón, D., Sanz Alonso, J.L., Guerra, M.T., Gaudêncio, M.J., Mendes, B., Henriques, V., Bajjouk, T., Bernard, M., Hily, C., Vasquez, M., Populus, J., Gonçalves, J.M.S. (2013). Atlantic Area Eunis Habitats. Adding new habitat types from European Atlantic coast to the EUNIS Habitat Classification. Technical Report No.3/2013 - MeshAtlantic, CCMAR-Universidade do Algarve, Faro, 72 pp.. CONTENTS SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 1 OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................... 1 CASE STUDIES ........................................................................................................................ 2 CASE STUDY 1 Portugal - Algarve ...........................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION -

Zootaxa, the Naticidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda)

Zootaxa 1770: 1–40 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) The Naticidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of Giglio Island (Tuscany, Italy): Shell characters, live animals, and a molecular analysis of egg masses THOMAS HUELSKEN, CARINA MAREK, STEFAN SCHREIBER, IRIS SCHMIDT & MICHAEL HOLL- MANN Thomas Huelsken, Department of Biochemistry I – Receptor Biochemistry, Ruhr University Bochum, Universitätsstrasse 150, 44780 Bochum, Germany, [email protected] Carina Marek, Department of Evolutionary Ecology and Biodiversity of Animals, Ruhr University Bochum, Universitätsstrasse 150, 44780 Bochum, Germany, [email protected] Stefan Schreiber, Department of Biochemistry I – Receptor Biochemistry, Ruhr University Bochum, Universitätsstrasse 150, 44780 Bochum, Germany, [email protected] Iris Schmidt, Institute for Marine Biology Dr. Claus Valentin (IfMB), Strucksdamm 1b, 24939 Flensburg, [email protected] Michael Hollmann, Department of Biochemistry I – Receptor Biochemistry, Ruhr University Bochum, Universitätsstrasse 150, 44780 Bochum, Germany, [email protected] Table of contents Abstract . 2 Introduction . 2 Materials and Methods . 4 Results . 9 Conclusion from molecular studies . 15 Description of species . 16 Family Naticidae Guilding, 1834 . 16 Subfamily Naticinae Guilding, 1834 . 16 The genus Naticarius Duméril, 1806 on Giglio Island . 16 Naticarius hebraeus (Martyn, 1786)—Fig. 6A [egg mass: Figs. 3, 11G, g] . 18 Naticarius stercusmuscarum (Gmelin, 1791)—Figs. 5A, B . 20 Notocochlis dillwynii (Payraudeau, 1826) [new comb.]—Fig. 6B [egg mass: Figs. 3, 11C, D, E, c, d, e] . 22 The genus Tectonatica Sacco, 1890 on Giglio Island . 23 Tectonatica sagraiana (Orbigny, 1842)—Figs. 7, 8A [egg mass: Figs. 3, 11F, H, I, f] . -

The 1940 Ricketts-Steinbeck Sea of Cortez Expedition: an 80-Year Retrospective Guest Edited by Richard C

JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHWEST Volume 62, Number 2 Summer 2020 Edited by Jeffrey M. Banister THE SOUTHWEST CENTER UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA TUCSON Associate Editors EMMA PÉREZ Production MANUSCRIPT EDITING: DEBRA MAKAY DESIGN & TYPOGRAPHY: ALENE RANDKLEV West Press, Tucson, AZ COVER DESIGN: CHRISTINE HUBBARD Editorial Advisors LARRY EVERS ERIC PERRAMOND University of Arizona Colorado College MICHAEL BRESCIA LUCERO RADONIC University of Arizona Michigan State University JACQUES GALINIER SYLVIA RODRIGUEZ CNRS, Université de Paris X University of New Mexico CURTIS M. HINSLEY THOMAS E. SHERIDAN Northern Arizona University University of Arizona MARIO MATERASSI CHARLES TATUM Università degli Studi di Firenze University of Arizona CAROLYN O’MEARA FRANCISCO MANZO TAYLOR Universidad Nacional Autónoma Hermosillo, Sonora de México RAYMOND H. THOMPSON MARTIN PADGET University of Arizona University of Wales, Aberystwyth Journal of the Southwest is published in association with the Consortium for Southwest Studies: Austin College, Colorado College, Fort Lewis College, Southern Methodist University, Texas State University, University of Arizona, University of New Mexico, and University of Texas at Arlington. Contents VOLUME 62, NUMBER 2, SUmmer 2020 THE 1940 RICKETTS-STEINBECK SEA OF CORTEZ EXPEDITION: AN 80-YEAR RETROSPECTIVE GUesT EDITed BY RIchard C. BRUsca DedIcaTed TO The WesTerN FLYer FOUNdaTION Publishing the Southwest RIchard C. BRUsca 215 The 1940 Ricketts-Steinbeck Sea of Cortez Expedition, with Annotated Lists of Species and Collection Sites RIchard C. BRUsca 218 The Making of a Marine Biologist: Ed Ricketts RIchard C. BRUsca AND T. LINdseY HasKIN 335 Ed Ricketts: From Pacific Tides to the Sea of Cortez DONald G. Kohrs 373 The Tangled Journey of the Western Flyer: The Boat and Its Fisheries KEVIN M. -

The Mitochondrial Genomes of the Nudibranch Mollusks, Melibe Leonina and Tritonia Diomedea, and Their Impact on Gastropod Phylogeny

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Mitochondrial Genomes of the Nudibranch Mollusks, Melibe leonina and Tritonia diomedea, and Their Impact on Gastropod Phylogeny Joseph L. Sevigny1, Lauren E. Kirouac1¤a, William Kelley Thomas2, Jordan S. Ramsdell2, Kayla E. Lawlor1, Osman Sharifi3, Simarvir Grewal3, Christopher Baysdorfer3, Kenneth Curr3, Amanda A. Naimie1¤b, Kazufusa Okamoto2¤c, James A. Murray3, James 1* a11111 M. Newcomb 1 Department of Biology and Health Science, New England College, Henniker, New Hampshire, United States of America, 2 Department of Biological Sciences, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire, United States of America, 3 Department of Biological Sciences, California State University, East Bay, Hayward, California, United States of America ¤a Current address: Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Science University, Manchester, New Hampshire, United States of America OPEN ACCESS ¤b Current address: Achievement First Hartford Academy, Hartford, Connecticut, United States of America ¤c Current address: Defense Forensic Science Center, Forest Park, Georgia, United States of America Citation: Sevigny JL, Kirouac LE, Thomas WK, * [email protected] Ramsdell JS, Lawlor KE, Sharifi O, et al. (2015) The Mitochondrial Genomes of the Nudibranch Mollusks, Melibe leonina and Tritonia diomedea, and Their Impact on Gastropod Phylogeny. PLoS ONE 10(5): Abstract e0127519. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127519 The phylogenetic relationships among certain groups of gastropods have remained unre- Academic Editor: Bi-Song Yue, Sichuan University, CHINA solved in recent studies, especially in the diverse subclass Opisthobranchia, where nudi- branchs have been poorly represented. Here we present the complete mitochondrial Received: January 28, 2015 genomes of Melibe leonina and Tritonia diomedea (more recently named T. -

Marinha Do Brasil Instituto De Estudos Do Mar Almirante Paulo Moreira Universidade Federal Fluminense Programa Associado De Pós-Graduação Em Biotecnologia Marinha

MARINHA DO BRASIL INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DO MAR ALMIRANTE PAULO MOREIRA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE PROGRAMA ASSOCIADO DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIOTECNOLOGIA MARINHA LAIS PEREIRA D' OLIVEIRA NAVAL XAVIER ECO-ENGENHARIA EM ÁREA PORTUÁRIA E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NA BIOINCRUSTAÇÃO E NA PREVENÇÃO DOS PROCESSOS DE BIOINVASÃO. ARRAIAL DO CABO 2018 MARINHA DO BRASIL INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DO MAR ALMIRANTE PAULO MOREIRA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE PROGRAMA ASSOCIADO DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIOTECNOLOGIA MARINHA LAIS PEREIRA D' OLIVEIRA NAVAL XAVIER ECO-ENGENHARIA EM ÁREA PORTUÁRIA E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NA BIOINCRUSTAÇÃO E NA PREVENÇÃO DOS PROCESSOS DE BIOINVASÃO. Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Instituto de Estudos do Mar Almirante Paulo Moreira e à Universidade Federal Fluminense, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Biotecnologia Marinha. Orientador: Dr. Ricardo Coutinho Coorientadora: Dra. Luciana V.R. de Messano ARRAIAL DO CABO 2018 LAIS PEREIRA D' OLIVEIRA NAVAL XAVIER ECO-ENGENHARIA EM ÁREA PORTUÁRIA E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NA BIOINCRUSTAÇÃO E NA PREVENÇÃO DOS PROCESSOS DE BIOINVASÃO. Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Estudos do Mar Almirante Paulo Moreira e à Universidade Federal Fluminense, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Biotecnologia Marinha. COMISSÃO JULGADORA: ___________________________________________________________________ Dr. Ricardo Coutinho Instituto de Estudos do Mar Almirante Paulo Moreira Professor orientador - Presidente da Banca Examinadora ___________________________________________________________________