PENLLERGAER (PENLLERGARE) Ref Number PGW (Gm) 54

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning, Design & Access Statement

DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT Land at Glanmarlais Care Home, Maespiode, Llandybie April, 2021 T: 029 2073 2652 T: 01792 480535 Cardiff Swansea E: [email protected] W: www.asbriplanning.co.uk PROJECT SUMMARY GLANMARLAIS CARE HOME, MAESPIODE, LLANDYBIE Description of development: Proposed full planning application for a new 3 storey standalone care facility Location: Land within the proximity of Glanmarlais Care Home, located to the south of Maespiode, Llandybie, Ammanford Date: April 2021 Asbri Project ref: S21.169 Client: T Padda Care Ltd N E M E T A T S S S E C C A & N G I S E D Asbri Planning Ltd Prepared by Approved by Unit 9 Oak Tree Court Mulberry Drive Daniel Lemon Richard Bowen, Cardiff Gate Business Park Name Cardiff Graduate Planner Director CF23 8RS T: 029 2073 2652 Date May 2021 May 2021 E: [email protected] W: asbriplanning.co.uk Revision - - M A Y 2 0 2 1 2 CONTENTS GLANMARLAIS CARE HOME, MAESPIODE, LLANDYBIE Section 1 Introduction 5 Section 2 Site Context and analysis 7 Section 3 Interpretation 11 Section 4 Planning Policy 13 T Section 5 N The Proposal 15 E M Section 6 E T Planning Appraisal 20 A T S Section 7 S Conclusion 22 S E C C A & N G I S E D M A Y 2 0 2 1 3 MAY 2 0 2 1 Site in regionalSite context plan GLANMARLAIS CARE HOME, MAESPIODE, LLANDYBIE 4 DE S I G N & A C CE S S S T A TE M E N T GLANMARLAIS CARE HOME, MAESPIODE, LLANDYBIE INTRODUCTION 1.1 The purpose of a Design & Access Statement (DAS) is to residential care home at Glanmarlais Care Home, Maespiode, provide a clear and logical document to demonstrate and Llandybie. -

A TIME for May/June 2016

EDITOR'S LETTER EST. 1987 A TIME FOR May/June 2016 Publisher Sketty Publications Address exploration 16 Coed Saeson Crescent Sketty Swansea SA2 9DG Phone 01792 299612 49 General Enquiries [email protected] SWANSEA FESTIVAL OF TRANSPORT Advertising John Hughes Conveniently taking place on Father’s Day, Sun 19 June, the Swansea Festival [email protected] of Transport returns for its 23rd year. There’ll be around 500 exhibits in and around Swansea City Centre with motorcycles, vintage, modified and film cars, Editor Holly Hughes buses, trucks and tractors on display! [email protected] Listings Editor & Accounts JODIE PRENGER Susan Hughes BBC’s I’d Do Anything winner, Jodie Prenger, heads to Swansea to perform the role [email protected] of Emma in Tell Me on a Sunday. Kay Smythe chats with the bubbly Jodie to find [email protected] out what the audience can expect from the show and to get some insider info into Design Jodie’s life off stage. Waters Creative www.waters-creative.co.uk SCAMPER HOLIDAYS Print Stephens & George Print Group This is THE ultimate luxury glamping experience. Sleep under the stars in boutique accommodation located on Gower with to-die-for views. JULY/AUGUST 2016 EDITION With the option to stay in everything from tiki cabins to shepherd’s huts, and Listings: Thurs 19 May timber tents to static camper vans, it’ll be an unforgettable experience. View a Digital Edition www.visitswanseabay.com/downloads SPRING BANK HOLIDAY If you’re stuck for ideas of how to spend Spring Bank Holiday, Mon 30 May, then check out our round-up of fun events taking place across the city. -

SA/SEA of the Deposit Revised

Revised Local 2018-2033 Development Plan DepositDeposit PlanPlan Sustainability Appraisal / Sustainability Appraisal Environmental Strategic (SA/SEA) Assessment Sustainability Appraisal / Sustainability Appraisal Environmental Strategic (SA/SEA) Assessment January 2020 Addendum Sustainability Appraisal (including Strategic Environmental Assessment - SA), Report. A further consultation period for submitting responses to the SA/SEA as part of the Deposit Revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 2018 – 2033 is now open. Representations submitted in respect of the further consultation on the Sustainability Appraisal (including Strategic Environmental Assessment -SA) must be received by 4:30pm on the 2nd October 2020. Comments submitted after this date will not be considered. Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Legislative Requirements ............................................................................................ 1 1.2 SA and the LDP Process ............................................................................................. 2 1.3 How the Council has complied with the Regulations .................................................... 3 Stage A .......................................................................................................................... 3 Stage B .......................................................................................................................... 3 Stage -

![[Document: File]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1079/document-file-441079.webp)

[Document: File]

Main House gross internal area: 00 sq m, 000 sq ft Annexe gross internal area: 00 sq m, 000 sq ft Total gross internal area: 00 sq m, 000 sq ft GRADE II LISTED FARMHOUSE & 5 FURTHER COTTAGES maerdy cottages taliaris, nr llandeilo, carmarthenshire, sa19 7da GRADE II LISTED FARMHOUSE & 5 FURTHER COTTAGES NESTLED IN A DELIGHTFUL COURTYARD SETTING WITH MATURE TREES maerdy cottages taliaris, nr llandeilo, carmarthenshire, sa19 7da Grade II listed 4 bed Farmhouse 5 further cottages: 1x4 bed, 2x3 bed, 2x2 bed Currently let as holiday/letting cottages Delightful electric gated courtyard setting Mature trees Landscaped grounds & gardens With a charming stream In all, about 1.2 acres (stms) Convenient location close to local tourist attractions Situation Maerdy cottages is set just south of the hamlet of Taliaris in the Dulais valley in the historic and beautiful county of Carmarthenshire that is known as the “Garden of Wales”. Close by are the Black Mountains, Llyne Brianne and Dinefwr Castle Estate, and within easy driving distance are several famous gardens including the National Botanical Gardens of Wales. Cardigan Bay and the excellent sandy beaches of the Gower are also within easy reach. Although enjoying a delightful rural valley location local road connections provide quick access to neighbouring towns including the ever popular market town of Llandeilo to the south being about 4 miles. The A40 road from Llandeilo takes you quickly to the larger administrative and shopping town of Carmarthen to the south-west (about 18.5 miles) while the A483 road from Llandeilo takes you south to junction 49 of the M4 at Pont Abraham taking you onto the rest of South Wales (Swansea about 28.5 miles, Cardiff about 68.5 miles) the Severn Bridge and beyond. -

13 Bangor Road, Johnstown, Wrexham, LL14 2SW

13 Bangor Road, Johnstown, Wrexham, LL14 2SW Situated within this popular location being convenient for the village of Johnstown which offers a good range of day-to-day amenities and within reach of the A483 road links to Chester/Wrexham/Oswestry is this three bedroom semi detached residence. The accommodation briefly consists porch entrance, entrance hall, cloakroom, sitting room, kitchen, dining room and sun room. On the first floor a landing with three bedrooms plus shower room. Gardens to front and rear. Off road parking and a garage. The property is being sold with NO ONWARD CHAIN. Offers in the region of £125,000 13 Bangor Road, Johnstown, Wrexham, LL14 2SW • Popular Location • Three Bedroom Semi • Two Reception & Sun Room • Ample Parking & Garage • Gardens Front & Rear • Double Glazing • No Onward Chain • EPC Rating F Sun Room Porch Entrance 8'4" x 7'3" (2.55m x 2.21m) With double glazed entrance door. Double With double glazed windows. Electric wall glazed window. Electric storage heater. Ceiling heater. Two wall light points. Fitted blinds. light point. Dado rail. Glazed door to hall. Kitchen Cloakroom 7'7" x 7'3" (2.30m x 2.22m) Comprising close coupled WC. Wash hand Fitted with a range of units having base units, basin. Double glazed window. Wall cabinet. drawers and matching suspended wall cabinets. Ceiling light point. Single drainer stainless steel sink unit with Entrance Hall mixer tap attachment. Space with plumbing for With staircase rising to the first floor landing. washing machine. Space for cooker. Tiled walls. Telephone point. Under stairs storage with Laminate style flooring. -

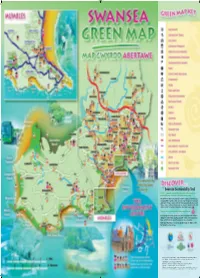

Swansea Sustainability Trail a Trail of Community Projects That Demonstrate Different Aspects of Sustainability in Practical, Interesting and Inspiring Ways

Swansea Sustainability Trail A Trail of community projects that demonstrate different aspects of sustainability in practical, interesting and inspiring ways. The On The Trail Guide contains details of all the locations on the Trail, but is also packed full of useful, realistic and easy steps to help you become more sustainable. Pick up a copy or download it from www.sustainableswansea.net There is also a curriculum based guide for schools to show how visits and activities on the Trail can be an invaluable educational resource. Trail sites are shown on the Green Map using this icon: Special group visits can be organised and supported by Sustainable Swansea staff, and for a limited time, funding is available to help cover transport costs. Please call 01792 480200 or visit the website for more information. Watch out for Trail Blazers; fun and educational activities for children, on the Trail during the school holidays. Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey Digital Map with the permission of the Controller of H.M.S.O. Crown Copyright - City & County of Swansea • Dinas a Sir Abertawe - Licence No. 100023509. 16855-07 CG Designed at Designprint 01792 544200 To receive this information in an alternative format, please contact 01792 480200 Green Map Icons © Modern World Design 1996-2005. All rights reserved. Disclaimer Swansea Environmental Forum makes makes no warranties, expressed or implied, regarding errors or omissions and assumes no legal liability or responsibility related to the use of the information on this map. Energy 21 The Pines Country Club - Treboeth 22 Tir John Civic Amenity Site - St. Thomas 1 Energy Efficiency Advice Centre -13 Craddock Street, Swansea. -

Review of Community Boundaries in the City and County of Swansea

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA FURTHER DRAFT PROPOSALS LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF PART OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA FURTHER DRAFT PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS 3. REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT PROPOSALS 4. ASSESSMENT 5. PROPOSALS 6. CONSEQUENTIAL ARRANGEMENTS 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 8. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT 9. THE NEXT STEPS The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 2039 5031 Fax Number: (029) 2039 5250 E-mail: [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 We the Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales (the Commission) are undertaking a review of community boundaries in the City and County of Swansea as directed by the Minister for Social Justice and Local Government in his Direction to us dated 19 December 2007 (Appendix 1). 1.2 The purpose of the review is to consider whether, in the interests of effective and convenient local government, the Commission should propose changes to the present community boundaries. The review is being conducted under the provisions of Section 56(1) of the Local Government Act 1972 (the Act). 1.3 Section 60 of the Act lays down procedural guidelines, which are to be followed in carrying out a review. In line with that guidance we wrote on 9 January 2008 to all of the Community Councils in the City and County of Swansea, the Member of Parliament for the local constituency, the Assembly Members for the area and other interested parties to inform them of our intention to conduct the review and to request their preliminary views by 14 March 2008. -

Chapter 11 Landscape and Visual Effects Abergelli PEIR 2018 – CHAPTER 11: LANDSCAPE and VISUAL

Chapter 11 Landscape and Visual Effects Abergelli PEIR 2018 – CHAPTER 11: LANDSCAPE AND VISUAL CONTENTS 11. Landscape and Visual ....................................................................................... 3 11.1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 3 11.2 Changes since the 2014 PEIR .................................................................. 3 11.3 Legislation, policy and guidance ............................................................... 4 11.4 Methodology .............................................................................................. 8 11.5 Baseline Environment ............................................................................. 21 11.6 Embedded Mitigation ............................................................................... 35 11.7 Assessment of Effects ............................................................................. 36 11.8 Mitigation and Monitoring ........................................................................ 47 11.9 Residual Effects ...................................................................................... 47 11.10 Cumulative Effects ................................................................................. 59 11.11 Conclusion ............................................................................................. 67 11.12 References ............................................................................................ 68 TABLES Table 11-1: Summary -

Sustainability Appraisal Report of the Deposit LDP November 2019

Carmarthenshire Revised Local Development Plan (LDP) Sustainability Appraisal Report of the Deposit LDP November 2019 1. Introduction This document is the Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Report, consisting of the joint Sustainability Appraisal (SA) and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA), of Carmarthenshire Council’s Deposit Revised Local Development Plan (rLDP).The SA/SEA is a combined process which meets both the regulatory requirements for SEA and SA. The revised Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan is a land use plan which outlines the location and quantity of development within Carmarthenshire for a 15 year period. The purpose of the SA is to identify any likely significant economic, environmental and social effects of the LDP, and to suggest relevant mitigation measures. This process integrates sustainability considerations into all stages of LDP preparation, and promotes sustainable development. This fosters a more inclusive and transparent process of producing a LDP, and helps to ensure that the LDP is integrated with other policies. This combined process is hereafter referred to as the SA. This Report accompanies, and should be read in conjunction with, the Deposit LDP. The geographical scope of this assessment covers the whole of the County of Carmarthenshire, however also considers cross-boundary effects with the neighbouring local authorities of Pembrokeshire, Ceredigion and Swansea. The LDP is intended to apply until 2033 following its publication. This timescale has been reflected in the SA. 1.1 Legislative Requirements The completion of an SA is a statutory requirement for Local Development Plans under Section 62(6) of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 20041, the Town and Country Planning (LDP) (Wales) Regulations 20052 and associated guidance. -

Price £475,000

Trewer, Tel: 01550 777790 Email: [email protected] Website: www.profilehomes.com Penybanc Farm Office, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire, SA19 9DU V.A.T. Registration No: 479 7600 00 Trewern Fawr, Talley, Llandeilo, SA19 7EJ A beautifully presented property in a delightful rural location enjoying far reaching views. Traditional 3 Bedroom Welsh Farmhouse, Detached Stone Barn (scope for conversion S.T.P.P.) Two pasture paddocks, all in circa 5 acres. Perfect Smallholding or private Equestrian use. Near the village of Talley with its historic Abbey ruins, church and lakes. Llandeilo 7 miles, Llandovery 9 miles, Lampeter 15 miles, Carmarthen 21 miles, (A48/M4 Link). This charming detached Period Residence is of stone construction with a slate roof. It has recently undergone improvements to include new Everest uPVC Sash windows and externally the beautiful stonework has been refurbished and dressed. Accommodation: Ground Floor: Kitchen/Breakfast Room, Boot Room, Utility / Cloakroom. Lounge with Inglenook fireplace, Dining Room, Sitting Room with large Inglenook fireplace. First Floor: 3 Bedrooms, separate Dressing Room and a Shower room. Externally: Large Detached Stone Barn which benefits from a new slate roof, offering potential for conversion into a residential annexe or holiday let accommodation, subject to planning approval. Land: The pastureland is flat to gently sloping within two enclosures perfect for those looking for a smallholding or equestrian property – the whole totalling c.5 acres. Location: The property is set amidst picturesque countryside and enjoys far reaching views across gently rolling countryside. There is one neighbouring property. Local villages and towns are within easy driving distance, as are Brechfa Forest and the Brecon Beacons National Park. -

Folklife A4 with Bleed 2014

Spring 2014 Number 29 NEWSLETTER ISSN 2043-0175 THE OLD SCHOOL HOUSE, MUCKROSS. ©TODDY DOYLE THE SOCIETY FOR FOLK LIFE STUDIES With so much of the site devoted to the interpreta- tion of rural domestic life, a second theme for the ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2014 conference will be the Irish kitchen and its food. Killarney, Republic of Ireland: Muckross also plays an important part within the work of the Killarney National Park. The third 11th to 14th September 2014 theme of the conference is Landscape Interpretation and the main excursion will explore a number of * 50 years of Muckross House sites within the national park. * The Irish kitchen * Landscape interpretation The conference sessions will be held in One of the key supporters of the Society has been the Lake Hotel, near Muckross House the staff and trustees of Muckross House and Tradi- (www.lakehotelkillarney.com). Built in 1820, the tional Farms in Killarney, Republic of Ireland. As core of the present hotel still exhibits the original the trust that both preserved this Victorian mansion elegant lounges with log fires. Later extended and and developed its open-air museum was established luxuriously appointed, the hotel has recently been in 1964, it seems very fitting that this year’s confer- refurbished, but has kept its old-world charm. ence returns to Killarney to reflect on the work of this famous heritage attraction over its first half If you wish to attend this year’s conference, please century. complete the enclosed application form and send it, 1 Newsletter of the Society for Folk Life Studies with a non-returnable deposit of £75, to the Confer- 2015 Conference ence Secretary (Steph Mastoris) at: National Water- at the front Museum, Maritime Quarter, Oystermouth Black Country Living Museum Road, Swansea, SA1 3RD, Wales. -

Conservation Management Plan October 2008

Penllergare Cadwraeth Cynllun Rheolaeth Hydref 2008 Conservation Management Plan October 2008 Ymddiriedolaeth Penllergare The Penllergare Trust Penllergare Cadwraeth Cynllun Rheolaeth Hydref 2008 Conservation Management Plan October 2008 Ymddiriedolaeth Penllergare The Penllergare Trust Penllergare Valley Woods PEN.060 __________________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • CRYNODEB GWEITHREDOL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 METHODOLOGY 3.0 SUMMARY HISTORY AND ANALYSIS 4.0 SITE CONTEXT 5.0 SIGNIFICANCE AND OBJECTIVES 6.0 GENERAL POLICIES AND PROPOSALS 7.0 AREA PROPOSALS FIGURES 1. Site Location and Context 2. Bowen’s and Yates’s county maps, 1729 and 1799 3. The Ordnance Survey Surveyor’s Drawing, 1813 4. The Ordnance Survey Old Series map, 1830 5. Tithe Map, 1838 6. The Garden 7. The Waterfall 8. The Upper Lake 9. The Valley 10. The Lower Lake 11. The Drive 12. The Quarry 13. The Orchid House 14. Fairy Land, The Shanty and Wigwam 15. Panorama of Penllergare 16. Ordnance Survey six-inch map, frst edition, 1875-8 17. Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map, second edition, 1898 18. Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map, third edition, 1916 19. Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map, fourth edition, 1936 20. Air Photograph, 1946 21. Ownership 22. Location of Sites and Monuments surveyed by Cambria Archaeology 23. Simplifed Ecological Habitats, 2002 __________________________________________________________________________________________ The Penllergare Trust 1 Nicholas Pearson Associates Ltd. Conservation