Watershed Collaborations: Entanglements with Common Streams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

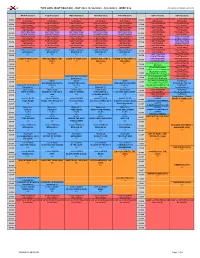

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

39 October 2013

ResilienceA VOICE OF THE NEW AGRARIANISM SPECIAL ISSUE: 2% SOLUTIONS FOR HUNGER, THIRST AND CO2 • 2% increase in soil carbon, produced by only • 2% of a nation’s population, for only • 2% of a nation’s Gross Domestic Product CAN MAKE ALL THE DIFFERENCE IN THE WORLD Profiles by Courtney White Quivira Coalition From the Executive Director 1413 Second Street, #1 Santa Fe, NM 87505 When Courtney and I sat down exactly one year ago to hammer out Phone: 505.820.2544 the details of Quivira’s graceful leadership transition, we were jointly Fax: 505.955.8922 motivated by one goal: put Courtney’s gifts as a storyteller to work. www.quiviracoalition.org With 16 years of work for the organization under his belt, together Avery C. Anderson with trips all over the world and thousands of hours in conversation Executive Director with the most innovative land stewards and food producers on Ext. 3# the planet, Courtney has accumulated a veritable treasure trove of [email protected] knowledge, one that would make the Library of Congress jealous! Courtney White That collection of knowledge alone is impressive, but Courtney’s Founder and Creative Director true gift is his skill at packaging it all in ways that make it accessible, Ext. 1# understandable and usable. These 2% Solutions describe massively [email protected] complex processes distilled into straightforward purity. They can be Catherine Baca pulled off the shelf and put to work on the ground this afternoon. Conference and Tribal Partnership From bats to pasture cropping, it’s all right here and within our reach Program Director to implement. -

Phelps Won't Testify in Rape Trial / Main 3

Phelps Won’t Testify in Rape Trial / Main 3 $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, April 26, 2012 www.chronline.com — Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online Lots of Shows to See This Spring Musicals / Life: A&E Get Ready for Summer With the 2012 Fighting for a Southwest Washington By Amy Nile [email protected] Tourism Guide Ten years ago, Nic Kuning traded drum lessons to learn / Insert how to fight. “Now, all my free time is de- Better voted to helping people punch Southwest people and I think I’m doing some good while I’m at it,” said Washington the now professional fighter. Kuning, who also owns and Tourism Guide 2012-2013 operates Arsenal Combat Sports in Longview, has partnered with Steve Coleman, of Centralia, to expand to a new location in Chehalis. The new site on Geary Street Life once housed a boxing club. Its New Business Aims closure left local kids with no- where to train, Kuning said. Kuning and Coleman to Help Struggling are working to remodel the 11,000-square-foot facility to Kids Stay Off Drugs open a combat sports academy and Out of Trouble please see FIGHTING, back page Warriors Win Wild Rivalry Match / Sports 1 Chris Geier / [email protected] Dustin Meyer, right, raises his hands in victory after winning a mixed martial arts bout against Centralia resident Rich Reevis at the Arsenal Combat Sports gym in Chehalis Saturday night. The Chronicle, Serving The Greater Weather Fishing Deaths Lewis County Area Since 1889 TONIGHT: Low 39 Lowland Lakes Open Watterson, Leonard Ray Follow Us on Twitter TOMORROW: High 57 (Leo), -

K-8Catalog 2015-2016

K-8 Catalog 2015-2016 ® Products and Professional Learning Participation for All Without citizens who can read and think critically, democracy is threatened, and our freedoms—personal, social, and political— are subject to dissolution. An independent, nonprofit educational organization, the Great Books Foundation fosters an inquiry-based approach to reading and discussion for students and adults in all walks of life. We believe that literacy and critical thinking help develop reflective and well-informed citizens. Our goal is to inspire people of all ages to become more knowledgeable, reflective, and engaged citizens. “I think that Junior Great Books . is extremely helpful. Not only does it help kids become better readers and have a better understanding of the book, but it also helps improve their confidence by not being afraid to speak up and share their opinions.” —Adamarys, eighth grader William Prescott Elementary, Chicago 6-year participant in Junior Great Books To learn more, please visit greatbooks.org. 2 read.think.discuss.grow.® Transform your classroom and watch your students exceed your expectations with help from Junior Great What’s Inside . Books and the Great Books Foundation. Our fiction and nonfiction products are designed to empower your K–8 Why Choose Junior Great Books?.............. 4 students to find the deeper connections and meanings in texts and to identify new ways of exploring issues and K–1 Read-Aloud .............................. 5 solving problems. Plus, our high-quality, customizable professional learning helps teachers become proficient Series 2 & 3................................... 6 at the intricacies of inquiry-based instruction. Series 4 & 5................................... 7 Inside this catalog you’ll find information on our elementary and middle school products as well as our Guided Reading . -

Crossword Cryptoquip Seek and Find Jumble Movies

B12 THE NEWS-ENTERPRISE CLASSIFIEDS FRIDAY, APRIL 27, 2012 CROSSWORD FRIDAY EVENING April 27, 2012 Cable Key: E-E’town/Hardin/Vine Grove/LaRue R/B-Radcliff/Fort Knox/Muldraugh/Brandenburg E R B 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 HCEC 2 25 2 Allegro ExCELebration Dinner Reel Talk Diversity United Way Crime Stoppers Health in the Elizabethtown City Council Meeting WAVE 3 News at WAVE 3 News at Who Do You Think You Are? Rob Grimm “Leave It to Beavers” Nick en- Dateline NBC (N) (CC) WAVE 3 News at (:35) The Tonight Show With Jay WAVE 3 6 3 7 (N) (CC) 7:30 Lowe examines his family history. counters a conflict. (N) (CC) 11 (N) Leno (N) (CC) Entertainment To- Inside Edition (N) Shark Tank A three-in-one nail polish. (:01) Primetime: What Would You 20/20 (CC) High School Ga- (:35) Nightline (N) Jimmy Kimmel WHAS 11 4 11 night (N) (CC) (N) (CC) Do? (CC) metime (CC) Live (CC) Wheel of Fortune Jeopardy! (N) Undercover Boss Philly Pretzel Facto- CSI: NY “Sláinte” Investigating a dis- Blue Bloods Danny and Jackie pro- WLKY News at (:35) Late Show With David Letter- WLKY 5 5 5 (N) (CC) (CC) ry CEO Dan DiZio. (N) (CC) membered body. (N) (CC) tect a witness. (N) (CC) 11:00PM (N) man (CC) Two and a Half The Big Bang The Finder “The Inheritance” Walter Fringe “Worlds Apart” Both teams fight WDRB News at (:45) WDRB Two and a Half 30 Rock “Into the The Big Bang WDRB 12 9 12 Men (CC) Theory (CC) looks for murderers. -

Pilot Earth Skills Earth Kills Murphy's Law Twilight's Last Gleaming His Sister's Keeper Contents Under Pressure Day Trip Unity

Pilot Earth Skills Earth Kills Murphy's Law Twilight's Last Gleaming His Sister's Keeper Contents Under Pressure Day Trip Unity Day I Am Become Death The Calm We Are Grounders Pilot Murmurations The Dead Don't Stay Dead Hero Complex A Crowd Of Demons Diabolic Downward Spiral What Ever Happened To Baby Jane Hypnos The Comfort Of Death Sins Of The Fathers The Elysian Fields Lazarus Pilot The New And Improved Carl Morrissey Becoming Trial By Fire White Light Wake-Up Call Voices Carry Weight Of The World Suffer The Children As Fate Would Have It Life Interrupted Carrier Rebirth Hidden Lockdown The Fifth Page Mommy's Bosses The New World Being Tom Baldwin Gone Graduation Day The Home Front Blink The Ballad Of Kevin And Tess The Starzl Mutation The Gospel According To Collier Terrible Swift Sword Fifty-Fifty The Wrath Of Graham Fear Itself Audrey Parker's Come And Gone The Truth And Nothing But The Truth Try The Pie The Marked Till We Have Built Jerusalem No Exit Daddy's Little Girl One Of Us Ghost In The Machine Tiny Machines The Great Leap Forward Now Is Not The End Bridge And Tunnel Time And Tide The Blitzkrieg Button The Iron Ceiling A Sin To Err Snafu Valediction The Lady In The Lake A View In The Dark Better Angels Smoke And Mirrors The Atomic Job Life Of The Party Monsters The Edge Of Mystery A Little Song And Dance Hollywood Ending Assembling A Universe Pilot 0-8-4 The Asset Eye Spy Girl In The Flower Dress FZZT The Hub The Well Repairs The Bridge The Magical Place Seeds TRACKS TAHITI Yes Men End Of The Beginning Turn, Turn, Turn Providence The Only Light In The Darkness Nothing Personal Ragtag Beginning Of The End Shadows Heavy Is The Head Making Friends And Influencing People Face My Enemy A Hen In The Wolf House A Fractured House The Writing On The Wall The Things We Bury Ye Who Enter Here What They Become Aftershocks Who You Really Are One Of Us Love In The Time Of Hydra One Door Closes Afterlife Melinda Frenemy Of My Enemy The Dirty Half Dozen Scars SOS Laws Of Nature Purpose In The Machine A Wanted (Inhu)man Devils You Know 4,722 Hours Among Us Hide.. -

Inquiry-Based Teaching and Learning Junior Great Books Grades K–5 ®

Professional Fall 2017–Summer 2018 Development For Educators Inquiry-Based Teaching and Learning Junior Great Books Grades K–5 ® Great Books Middle School Grades 6–8 Great Books Seminar Grades 9–12 How to Get Started Grades K–12 Great for Students and Teachers What Is the Great Books Foundation? The Great Books Foundation provides outstanding classroom materials and inspiring professional development. We help students get the most out of reading and interacting with their teachers and classmates, while providing instruction and support in Shared Inquiry, a method of learning that gives teachers the approach they need to help their students succeed. In Shared Inquiry, students —guided by their teacher —explore fiction and nonfiction texts by discussing open-ended questions and sharing responses and insights. In schools that use our classroom materials and method of teaching and learning, students consider important ideas, discover how these ideas have shaped events of the past, and learn the critical thinking skills that will prepare them for the future. Teachers who use Great Books K–12 programs: Students who participate in Great Books learn to: • Use great questions to spur deep thinking • Read and understand texts more completely • Engage students through interpretive activities • Listen to others’ ideas and Shared Inquiry discussion • Confidently state their own opinions and back • Use inquiry-based instruction throughout the them up with evidence from the text curriculum • Express ideas in writing “I think Junior Great “ I like when I get to share Books is an important my thoughts with the component of a bal- whole class. It makes me anced literacy program, feel kind of like happy, because it really incor- because everyone is pay- porates the reading, ing attention.