Right to Health Introduction: Connecting Health and Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cbc Radio One, Today

Stratégies gagnantes Auditoires et positionnement Effective strategies Audiences and positioning Barrera, Lilian; MacKinnon, Emily; Sauvé, Martin 6509619; 5944927; 6374185 [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Rapport remis au professeur Pierre C. Bélanger dans le cadre du cours CMN 4515 – Médias et radiodiffusion publique 14 juin 2014 TABLE OF CONTENT ABSTRACT ......................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 3 CBC RADIO ONE, TODAY ...................................................................... 4 Podcasting the CBC Radio One Channel ............................................... 6 The Mobile App for CBC Radio One ...................................................... 7 Engaging with Audiences, Attracting New Listeners ............................... 9 CBC RADIO ONE, TOMORROW ............................................................. 11 Tomorrow’s Audience: Millennials ...................................................... 11 Fishing for Generation Y ................................................................... 14 Strengthening Market-Share among the Middle-aged ............................ 16 Favouring CBC Radio One in Institutional Settings ................................ 19 CONCLUSION .................................................................................... 21 REFERENCES .................................................................................... -

News from Mhcc News from Mhcc News from Mhcc News

MENTAL HEALTH NEWS FROM MHCC COMMISSIONCOMMISSION DE LA OF SANTÉ NEWS FROM MHCC MENTALECANADA DU CANADANEWS FROM MHCC NEWS FROM MHCC VOLUME 3, ISSUE 3 WINTER 2011 ABOUT At Home/Chez Soi Celebrates A Year of Milestones THE MHCC The Mental Health Commission of Canada works towards its goals by focusing on five major initiatives: Mental Health Strategy for Canada At Home/Chez Soi: A national research project on mental health and homelessness Opening Minds: An anti‑stigma initiative Knowledge Exchange Centre More than 600 homeless Partners for Mental Health: A social movement participants are now housed thanks to the project. Mario Lopes, landlord involved in Eight Advisory Committees Since its official five-city launch one year ago, the the At Home Winnipeg project. provide insight to the Commission on important Mental Health Commission of Canada’s (MHCC) mental health issues: national research project on mental health and homelessness has much to celebrate. At Home/Chez Soi participant update as Family/Caregivers of January 7, 2011: Child and Youth The five sites of the At Home/Chez Soi project — Moncton, Montréal, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Vancouver Science — are investigating the best ways to help homeless Vancouver 428 First Nations, Inuit and Métis people living with a mental illness. Over the past 12 Winnipeg 343 Service Systems months there have been many positive signs. Mental Health and the Law Site coordinators report stories of participants settling Toronto 409 Seniors into their new homes and pursuing job opportunities. Montreal 350 Workforce Others notice a renewed stability within participants’ lives, some of whom are forming fresh relationships Moncton 148 and making use of new support systems. -

CJFE 2013 Gala Pub 11-28 Nocoilsspreads

2013 “ The right of free expression is critical, and when we protect it we protect so much more..” JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH – Peter Mansbridge, CBC News Chief Correspondent SMTWTFS SMTWTFS SMTWTFS 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 1 2 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 “Those who try to silence the likes of young 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Malala Yousafzai, who so boldly stood up 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 to the Taliban, continue to sicken. 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 May there be more Malalas and fewer cowards with guns” APRIL MAY JUNE – Adrienne Arsenault, CBC News Correspondent - The National SMTWTFS SMTWTFS SMTWTFS 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 1 “ No matter where the brave voice is raised or the story told, 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 it is our freedom too. ” 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 – Alison Smith, CBC News. -

May 25, 2017 Full Episode Transcript

The Current with Anna Maria Tremonti Thursday May 25, 2017 May 25, 2017 full episode transcript Note: Transcripts may contain errors. If you wish to re-use all, or part of, a transcript, please contact CBC for permission. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print. Copyright © CBC 2016 The Current Transcript for May 25, 2017 Host: Duncan McCue STORIES FROM THIS EPISODE Prologue » Gang trial reveals alleged murder plot against B.C. crime reporter Kim Bolan » At 31, she was diagnosed with autism. Here's how it enriched her life » 'It is a crisis': A father's mission to save drug-addicted teens from dying » After mauling death, dog cull may be only solution argues veterinarian » http://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-may-25-2…24/may-25-2017-full-episode-transcript-1.4131721#segment4 2017-05-27, 1037 PM Page 1 of 43 Audio Link: http://www.cbc.ca/player/play/953247811517/ Facebook Twitter Email DM: Hi. I'm Duncan McCue sitting in for Anna Maria Tremonti and you're listening to The Current. SOUNDCLIP VOICE 1: Donnelly was a loving, caring mother. She put her daughter first. She lived with us ever since she was five. VOICE 2: It's like a nightmare. You can’t get up. Hopefully we can round up what dogs are around that are responsible and put them down. DM: Donnelly Rose Eaglestick's aunt and uncle are still in mourning. The 24- year-old woman was found dead earlier this month. The RCMP confirmed the young mother had been killed by a pack of stray dogs while walking home one night. -

List of Participants to the Third Session of the World Urban Forum

HSP HSP/WUF/3/INF/9 Distr.: General 23 June 2006 English only Third session Vancouver, 19-23 June 2006 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS TO THE THIRD SESSION OF THE WORLD URBAN FORUM 1 1. GOVERNMENT Afghanistan Mr. Abdul AHAD Dr. Quiamudin JALAL ZADAH H.E. Mohammad Yousuf PASHTUN Project Manager Program Manager Minister of Urban Development Ministry of Urban Development Angikar Bangladesh Foundation AFGHANISTAN Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Dhaka, AFGHANISTAN Eng. Said Osman SADAT Mr. Abdul Malek SEDIQI Mr. Mohammad Naiem STANAZAI Project Officer AFGHANISTAN AFGHANISTAN Ministry of Urban Development Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Mohammad Musa ZMARAY USMAN Mayor AFGHANISTAN Albania Mrs. Doris ANDONI Director Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Telecommunication Tirana, ALBANIA Angola Sr. Antonio GAMEIRO Diekumpuna JOSE Lic. Adérito MOHAMED Adviser of Minister Minister Adviser of Minister Government of Angola ANGOLA Government of Angola Luanda, ANGOLA Luanda, ANGOLA Mr. Eliseu NUNULO Mr. Francisco PEDRO Mr. Adriano SILVA First Secretary ANGOLA ANGOLA Angolan Embassy Ottawa, ANGOLA Mr. Manuel ZANGUI National Director Angola Government Luanda, ANGOLA Antigua and Barbuda Hon. Hilson Nathaniel BAPTISTE Minister Ministry of Housing, Culture & Social Transformation St. John`s, ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 1 Argentina Gustavo AINCHIL Mr. Luis Alberto BONTEMPO Gustavo Eduardo DURAN BORELLI ARGENTINA Under-secretary of Housing and Urban Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Development Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ms. Lydia Mabel MARTINEZ DE JIMENEZ Prof. Eduardo PASSALACQUA Ms. Natalia Jimena SAA Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Session Leader at Networking Event in Profesional De La Dirección Nacional De Vancouver Políticas Habitacionales Independent Consultant on Local Ministerio De Planificación Federal, Governance Hired by Idrc Inversión Pública Y Servicios Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ciudad Debuenosaires, ARGENTINA Mrs. -

Cloudfront.Net

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Societe Radio-Canada ••• CBC est!' Radio-Canada Mr. Jason Plotz 2-44 Clarey Avenue Ottawa, Ontario KI S 2R 7 Our file: A-2015-00 I 02 I YJP Dear Mr. Plotz, This is in response to your request under the Access to Information Act (Act) dated March 21, 2016, received by our office on March 24, 2016, for the following: ""Provide copies of all documents, including memos, briefingnotes, e-mails, correspondence, etc. regarding any discussions about sponsorships or coverage to mark David Suzuki's 80th Birthday, since Janua,y 1, 2016. "" Attached are copies of all the accessible documents which you requested under the Act. Please note that certain information has been severed from them pursuant to sections 16(2), l 8(b ), 19( I) and 21( I)(b) of the Act. Some of the requested infom1ationrelates also to our programming activities, and is excluded from t e application of the Act pursuant to section 68.1, which states: "68.1 This Act does not apply to any information that is under the contr I of th� a adian Broadcasting Corporation that relates to its journalistic, creative or programming acti 'ties other than information that relates to its general administration." Please note that CBC reserves the right to claim exemptions pursuant to the Act. Please be advised that you are entitled to complain to the Information Commissioner concerning the processing of your request within sixty days of the receipt of this notice. In the event you decide to avail yourself of this right, your notice of complaint should be addressed to: Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada 30 Victoria Street Gatineau, Quebec KI A I H3 Should you have any questions concerning the processing of your request, please contact Yves Lapierre at 613-288-6248. -

Beyond Borders Media Awards Announces 2010 Nominees

CANADA’S GLOBAL VOICE AGAINST CHILD SEXUAL EXPLOITATION Head Office: 387 Broadway, Winnipeg, MB R3C 0V5 Tel: (204) 793-7080 Fax: (204) 452-1333 www.beyondborders.org September 28, 2010 MEDIA RELEASE Beyond Borders Media Awards announces 2010 nominees Winnipeg – Beyond Borders, Canada’s global voice against child sexual exploitation, announced the nominees in its annual, national, bilingual media awards today. The awards program, in its eighth year, honours journalists and documentary makers for exceptional coverage of issues related to child sexual exploitation. “The media play an important role in terms of the work that Beyond Borders does,” states event co-chair, Deborah Zanke. “Journalists and documentary makers help to raise awareness, point out areas of the justice and social services system that aren’t working to protect children and motivate the public and politicians to take action on issues related to the sexual abuse of children.” The 2010 nominees are as follows: Print (English) 1. Elaine O’Connor, Mean Streets in Maisonneuve Magazine, Spring 2010 2. Laura Czekaj, Child Sex Slaves: Fighting a world of abuse, terror, Ottawasun.com, September 17, 2009. 3. Cynthia Vukets, In a small Kenyan village, girls are speaking up, The Toronto Review, May 31, 2010. 4. Jessica Leeder, From her dolls to her husband in a single day, The Globe and Mail, September 22, 2009. 5. Jessica Leeder, Fighting back against sex crimes, The Globe and Mail, March 29, 2010. 6. Tamara Cherry, No way out; Falling through the cracks; The story of Eve (series), The Toronto Sun, October – November 2009. 7. Tamara Cherry, Eve’s dark past revealed/Ex-Sex slave makes plea, The Toronto Sun, May 3-4, 2010. -

Master of Arts in History, Queen's University. Super

Dr. Christos Aivalis SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow Department of History University of Toronto Education: 613-929-4550 [email protected] 2010-2015: Ph.D. in History at Queen’s University 2009-2010: Master of Arts in History, Queen’s University. Supervisor: Ian McKay. 2005-2009: Bachelor of Arts (hons.) in History and Political Science, University of New Brunswick. Dissertation: “Pierre Trudeau, Organized Labour, and the Canadian Social Democratic Left, 1945-2000.” Supervisor: Ian McKay. Committee members: Timothy Smith, Jeffery Brison, Pradeep Kumar, and Gregory Kealey. Post-Graduate Scholarships and Awards: 2017- 2019: SSHRC Post-Doctoral Fellowship Award (held at the University of Toronto, Department of History. Supervisor: Dr. Sean Mils 2016-17: Nominee—Eugene Forsey Prize in Canadian Labour and Working-Class History— Best Graduate Thesis 2016: Queen’s University Department of History’s most Outstanding Doctoral Dissertation Prize 2016: Queen’s University Award for Scholarly Research and Creative Work and Professional Development 2016: Departmental Nominee—John Bullen Prize for Canadian Historical Association’s best Doctoral Dissertation 2015: Nominee—Canadian Committee for Labour History Article Prize. 2015: Nominee—New Voices in Labour Studies—Best Paper Prize. 2015: Nominee—Jean-Marie-Fecteau Prize for Canadian Historical Association’s Best Graduate Student Article. 2013-2015: Queen’s University Graduate Scholarship. 2013-2014: Finalist—Queen’s University History Department Teaching Award. 2010-2013: SSHRC Joseph-Armand Bombardier CGS Doctoral Scholarship. 2010: Queen’s University Tri-Council Award. 2010: Ontario Graduate Scholarship (declined). 2009: SSHRC Master's Scholarship. 2009: Queen’s University Tri-Council Award. Teaching and Research Experience: Fall 2018-Winter 2019: Adjunct Professor for History 102: History of Canada, Royal Military College of Canada. -

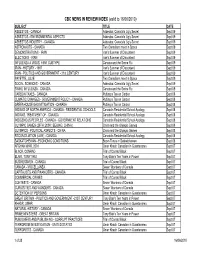

CBC NEWS in REVIEW INDEX (Valid to 16/06/2010)

CBC NEWS IN REVIEW INDEX (valid to 16/06/2010) SUBJECT TITLE DATE ASBESTOS - CANADA Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 ASBESTOS - ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 ASBESTOS INDUSTRY - CANADA Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 ASTRONAUTS - CANADA Two Canadians meet in Space Sept.09 DEMONSTRATIONS - IRAN Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 ELECTIONS - IRAN Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 INFLUENZA A VIRUS, H5N1 SUBTYPE Canada and the Swine Flu Sept.09 IRAN - HISTORY - 1997 Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 IRAN - POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT - 21st CENTURY Iran's Summer of Discontent Sept.09 PAYETTE, JULIE Two Canadians meet in Space Sept.09 SOCIAL SCIENCES - CANADA Asbestos: Canada's Ugly Secret Sept.09 SWINE INFLUENZA - CANADA Canada and the Swine Flu Sept.09 CARBON TAXES - CANADA Putting a Tax on Carbon Sept.08 CLIMATIC CHANGES - GOVERNMENT POLICY - CANADA Putting a Tax on Carbon Sept.08 GREENHOUSE GAS MITIGATION - CANADA Putting a Tax on Carbon Sept.08 INDIANS OF NORTH AMERICA - CANADA - RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 INDIANS, TREATMENT OF - CANADA Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES - CANADA - GOVERNMENT RELATIONS Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 OLYMPIC GAMES (29TH :2008 : BEIJING, CHINA) China and the Olympic Games Sept.08 OLYMPICS - POLITICAL ASPECTS - CHINA China and the Olympic Games Sept.08 RECONCILIATION (LAW) - CANADA Canada's Residential School Apology Sept.08 SASKATCHEWAN - ECONOMIC CONDITIONS Boom Times in Saskatchewan -

WINTER 1997 ~ $3.95 TABLE of CONTENTS the FIRST WORD THC CANADIAN ASSOCIATION of JOURNALISTS T:ASSOCIATION Canadiet\~E DES JOURNALISTES

' ~FJJA , THE CANADIAN ASSOCIATION ' OF JOURNALISTS L'ASSOCIATION CANADIENNE DES JOURNALISTES VOL 3 • NO.4 WINTER 1997 ~ $3.95 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE FIRST WORD THC CANADIAN ASSOCIATION OF JOURNALISTS t:ASSOCIATION CANADIEt\~E DES JOURNALISTES F1KST WORD ........................................................ 3 1HE LOf OF COWMNISIS WHAT MAKES THEM TICK? NEW ON 1HE NET Arts\ve ting this question could piUvide valuable insight MEDIA LISTEN! G TO THE RADIO WITH THE CLICK into the views they express. The business of journalism VOLUME 3 • ;-.!UMBER 4 • WINTER 1997 OF A MOUSE By Mich:1Cl Cdxlen ......................................................... 18 The lntemet isn't just a repositoty for lots of text and Publisher: Wendy Mcl ellan photographs. Many mdio stations, including public JOBS ON-LINE Editor: David McKie broodcastets sud1 as the CBC and BBC, can be hea~d in jOBS IN Ti lE NEW MEDIA is deaf to pleas for the preservation of a nation ers who question his motives and paint him as The Books Editor: Lynne Van Luven real Lin1e on the Net. impcmant thing is that there rue jobs out thete in al culture." the ,~Jiain . He has said that hes buying news By julian Sher ............................................................................ 4 new media, and they sotcly need joumalists with new Copy Editor: Laurel Hyau skills. And even funher afield, the Australian papers to save them He has asked his c1itics to "hat a year it was. For many jour wait and see what hes able to do with newspa Layout and design: Chris Barnett 1HE WRII1NG TOOLBOX By Mindy McAt.iams .......................................................... 19 Bmadcasting Corporation is also facing the Legal Advisor: Peter M. -

Bishop's Court Opens As a Temporary Shelter

JANUARY 2019 THE NEW BRUNSWICK ANGLICAN / 1 A milestone Advent Talks Assassination Mothers’ Union in the Parish kicks off of an gathers for of St. George the season Archbishop conference Page 6 Page 8-9 Page 11 Page 14 A SECTION OF THE ANGLICAN JOURNAL janUARY 2019 SERVING THE DIOCESE OF FREDERICTON Bishop’s Court opens as a temporary shelter BY GISELE MCKNIGHT with the conviction that the answer was in opening the doors After a week of twists and turns of Bishop’s Court. worthy of a suspense novel, The building has been used Bishop’s Court, the designated for various purposes in the past residence of the Bishop of Fred- five years, but as of late Septem- ericton, has been opened as a ber, sat empty. temporary emergency shelter in The Community Action downtown Fredericton. Group on Homelessness had Its first night of operation was been seeking a temporary Out Saturday, Dec. 1, giving warmth Of The Cold structure to operate and shelter to up to 20 people. daily from 8 p.m. to 7:30 a.m. “It took a while to get the I’s for 20 weeks until March, and dotted and the T’s crossed, but the group eagerly accepted the we made it,” said Bishop David bishop’s offer. Edwards. “I am very pleased that “This is an important issue in the temporary homeless shelter the major cities of New Bruns- has opened in Bishop’s Court. wick and something with which The folks who have used it over churches have to be involved,” the initial two nights demon- said Bishop David in late No- strate the need.” vember. -

Jennifer Mcguire, General Manager and Editor in Chief, CBC News

Jennifer McGuire, General Manager and Editor in Chief, CBC News Jennifer McGuire has been the General Manager and Editor in Chief of CBC News since May 2009. In March 2011, she assumed responsibility for managing CBC’s local and regional markets on all platforms. McGuire is responsible for: CBC News Network, the No. 1 news network in Canada; all news programming on CBC Television and Radio, including The National, World at Six, World Report and the fifth estate; all local programming on CBC Radio and television, including flagship morning shows (such as Metro Morning); Canada’s No. 1 online news site, CBCNews.ca; and all mobile applications of CBC News including CBC News Airport Express services. McGuire is now also responsible for the success of several new local initiatives, including the innovative hyperlocal project launched in Hamilton Ontario. Formerly Executive Director of CBC Radio, McGuire was responsible for all of radio, including CBC Radio One, CBC Radio 2, CBC Radio on Sirius and CBC Radio 3. Under her leadership, CBC Radio achieved unprecedented ratings success. McGuire led the repositioning of CBC Radio 3 and the launch of CBC Radio on Sirius Satellite Radio. She also led the redevelopment and repositioning of CBC Radio 2. Prior to accepting the position of Executive Director, CBC Radio, McGuire served as the Executive Director of Programming for CBC Radio, a position she took up in May 2003. It was during her tenure that programs such as Q, The Debaters, Wiretap, Afghanada and Randy Bachman’s Vinyl Tap were launched. Before that, McGuire served as Acting Head of CBC Radio Current Affairs, where she led a number of significant initiatives, including the creation of what is now one of CBC Radio One’s flagship current affairs programs, The Current with Anna Maria Tremonti.