Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physician-Assisted Death: a Selected Annotated Bibliography*

LAW LIBRARY JOURNAL Vol. 111:1 [2019-3] Physician-Assisted Death: A Selected Annotated Bibliography* Alyssa Thurston** Physician-assisted death (PAD), which encompasses physician-assisted suicide and physician-administered euthanasia, has long been controversial. However, recent years have seen a trend toward legalizing some form of PAD in the United States and abroad. The author provides an annotated bibliography of sources concerning PAD and the many issues raised by its legalization. Introduction ..........................................................32 A Note About Terminology ...........................................33 Case Law, Legislation, and Related Resources ..............................35 U.S. Supreme Court Cases ............................................35 States Where Physician-Assisted Suicide Is Legal ........................39 California ........................................................39 Colorado ........................................................41 District of Columbia ..............................................41 Hawai‘i ..........................................................41 Montana .........................................................42 Oregon. ..........................................................43 Vermont .........................................................44 Washington ......................................................45 Other States ........................................................45 Current Awareness Resources. 48 Legalizing Physician-Assisted Death. .48 General -

New Approach to Ethics in Fertility

Revista Latinoamericana de Hipertensión ISSN: 1856-4550 [email protected] Sociedad Latinoamericana de Hipertensión Venezuela New approach to ethics in fertility Mahtab, Sattari; Parvin Alsadat, Eslamnik; Ahmad, Rozian; Maryam Abbasi, Jebelli New approach to ethics in fertility Revista Latinoamericana de Hipertensión, vol. 14, no. 6, 2019 Sociedad Latinoamericana de Hipertensión, Venezuela Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=170262862002 Copyright © Sociedad Venezolana de Farmacología y de Farmacología Clínica y Terapéutica. Derechos reservados. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de todo el material contenido en la revista sin el consentimiento por escrito This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Revista Latinoamericana de Hipertensión, 2019, vol. 14, no. 6, Enero-Marzo, ISSN: 1856-4550 Artículos New approach to ethics in fertility Sattari Mahtab Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Irán id=170262862002 [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4539-6689 Eslamnik Parvin Alsadat Clinical Research Development Unit Beheshti Hospital, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Irán http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5364-6812 Rozian Ahmad Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Irán http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5250-6941 Jebelli Maryam Abbasi Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan,, Irán Abstract: : When there is talk of morality in the health of fertility, there are many ethical issues that can be addressed. e strenuous debate about "the onset of human life" is closely related to "fertility health." e purpose of this study is to look at the New Approach to Ethics in Fertility. -

Medicine and Law World Association for Medical Law

An international publication dealing with medicolegal issues. Articles, court decisions, and legislation on: Medical law, forensic medicine, sexology and law, psychiatry and law, psychology and law, dentistry and law, nursing law, pharmaceutical law, medical ethics, clinical criminology, drugs, alcohol, child abuse, medical experimentation, genetic engineering, organ transplantation, abortion, contraception, sterilization, euthanasia, religion, AIDS, etc. World Association for Medical Law Manuscripts should be submitted to the Editorial Office: The International Center for Health, Law and Ethics, University of Haifa, Haifa 31905, Israel E-Mail: [email protected] Founder and Editor-in-Chief (1980-2010): Amnon Carmi Executive Editorial Committee: Administrative Officer: Ava Van Dam; English Roy G Beran (Australia) (Editor-in-Chief) Editor: John Kim; Graphic Designer: Raul Vergara; David Townend (Netherlands) (Law & Ethics) Indexing: John Kim; Richard Wilbur (USA) (Legal Medicine) WAML Administrative Officer Professor Albert Lee (Hong Kong) (Medicine, and Publisher Liaison: Denise McNally; Law and Bioethics) Previous Editors in Chief: Amnon Carmi (Founder) (Israel); Mohammed Wattad (Israel) Editorial Board Abu Ramadan, Moussa Dutra Caue Nissim, Sara Adlan, Abdallah Efron, Yael Noguchi, Thomas Aguiar-Guevara, Rafael Ferris, Lorraine Pereira, André G. D. Bal, Sonny Fimate, Lallukhum Piga, Antonio Beran, Roy Frenkel, David Rudnick Abraham Berger, Ken Hrevtsova, Radmila Shalata, Abed Beyleveld, Deryck Kassim, Puteri N. J. Tabak, Nili Blum, John Kegley, Jacquelyn Talib, Norchaya Cotler, Miriam Keidar, Daniella Townend, Prof. David Dangata, Yohanna Khalaila, Rabei Van Wyk, Christa Dantas, Eduardo Le Blang, Theodore Montanari Vergallo, Gianluca Den Exter, Andre Lee, Albert Weedn, Prof. Victor Dickens, Bernard Lupton, Michael Wilbur, Richard DuMont, Janice Martens, Willem Wolfman, Samuel Dute, Joseph Mester, Roberto Zaremski, Mr. -

Medical Law: Text and Materials

Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 26 1991 MEDICAL LAW: TEXT AND MATERIALS. By Ian Kennedy and Andrew Grubb. London: Butterworths. 1989. 1210 Pp. $50.00 approx. George P. Smith II Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp Recommended Citation George P. Smith II, MEDICAL LAW: TEXT AND MATERIALS. By Ian Kennedy and Andrew Grubb. London: Butterworths. 1989. 1210 Pp. $50.00 approx., 7 J. Contemp. Health L. & Pol'y 443 (1991). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp/vol7/iss1/26 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 199 1] Abortion and Protection of the Human Fetus While ABORTION AND PROTECTION OF THE HUMAN FETUS settles neither the moral question nor the more basic metaphysical issues at stake, as a result of the data presented, it clearly suggests the need for principled inquiry. The basic question remains: Is there any freedom which justifies such a large scale taking of human life? MEDICAL LAW: TEXT AND MATERIALS. By Ian Kennedy and Andrew Grubb. London: Butterworths. 1989. 1210 Pp. $50.00 approx. Reviewed by George P. Smith, I1* I. Although human anatomy-and physiology are taken as the same world wide, individual cultures differ in the basic organization and the delivery of health care services. Thus, while Americans are regarded as probably more health conscious than any other culture, it remains the only industrialized country (with the exception of South Africa) that has failed to create a sys- tem of national health insurance. -

Medicine and Law, Is Available Through Hein's Current Content Subscription Model, Including Both Online and Print Subscriptions

ONLY COMPLETE ARCHIVE AVAILABLE ONLINE! World Association for Medical Law MedicineMcGill Institute and Law of Air and Space Law LeadingPublications International Medical Journal The official journal of the World Association for Medical Law, Medicine and Law, is available through Hein's current content subscription model, including both online and print subscriptions. The World Association for Medical Law was established in 1967. The purpose of the association is to encourage the study and discussion of health law, legal medicine and ethics, in order to benefit society and the advancement of human rights. The goal of the World Health Association for Medical Law is to further the study of the consequences in jurisprudence, legislation, and ethics of developments in medicine, health care, and related sciences. About Medicine and Law Medicine and Law is an international publication dealing with medico-legal issues. The journal is comprised of original articles, court decisions, and legislation on topics including medical law, forensic medicine, sexology and law, psychiatry and law, psychology and law, dentistry and law, nursing law, pharmaceutical law, medical ethics, clinical criminology, drugs, alcohol, child abuse, medical experimentation, genetic engineering, and many more. The journal has been published for more than 30 years and includes more than 2,000 articles written by hundreds of experts from around the world. The journal has been listed by the renowned Kennedy Institute of Ethics as a "priority journal". Available in Print & Online via Hein's Current Content Subscription Model Medicine and Law Sampling of Articles Found in Medicine and Law • Tools to Foster Trust in Sharing Healthcare Data: Toward a Common Language for Regulatory Metadata - Patrick J. -

Medical Law and Ethics

Review article UDC: 614.253 doi:10.5633/amm.2013.0310 MEDICAL LAW AND ETHICS Sunčica Ivanović1, Čedomirka Stanojević1, Slađana Jajić2, Ana Vila3, Svetlana Nikolić4 The subject of interest in this article is the importance of knowing and connecting medical ethics and medical law for the category of health workers. The author believes that knowledge of bioethics which as a discipline deals with the study of ethical issues and health care law as a legal discipline, as well as medical activity in general, result in the awareness of health professionals of human rights, and since the performance of activities of health workers is almost always linked to the question of life and death, then the lack of knowledge of basic legal acts would not be justified at all. The aim of the paper was to present the importance of medical ethics and medical law among the medical staff. A retrospective analysis of the medical literature available on the indexed base KOBSON for the period 2005-2010 was applied. Analysis of all work leads to the conclusion that the balance between ethical principles and knowledge of medical law, trust and cooperation between the two sides that appear over health care can be considered a goal that every health care worker should strive for. This study supports the attitude that lack of knowledge and non-compliance with the ethical principles and medical law when put together can only harm the health care worker. In a way, this is the message to health care professionals that there is a need for the adoption of ethical principles and knowledge of medical law, because the most important position of all health workers is their dedication to the patient as a primary objective and the starting point of ethics. -

SARA GERKE [email protected] 617-495-5147 ♦ 23 Everett Street, Cambridge, MA 02138

SARA GERKE [email protected] 617-495-5147 ♦ 23 Everett Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Aug. 2018–present The Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, United States of America Research Fellow, Medicine, Artificial Intelligence, and Law The Project on Precision Medicine, Artificial Intelligence, and the Law (PMAIL); collaborators at the Center for Advanced Studies in Biomedical Innovation Law (CeBIL) at the University of Copenhagen; this research is supported by a Novo Nordisk Foundation-grant for a Collaborative Research Programme (grant agreement number NNF17SA027784) Apr. 2018–June 2018 The Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, United States of America Visiting Researcher The ethics and law of in vitro gametogenesis (IVG) in the United States (U.S.) and Europe, reproductive and regenerative medicine, U.S. patent and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) law Oct. 2016–Mar. 2018 Institute for German, European and International Medical Law, Public Health Law and Bioethics of the Universities of Heidelberg and Mannheim, Germany General Manager External presentation of the Institute, contact person for inquiries, supervision of the 24 student assistants, organization of conferences (e.g., Ethics Symposium), acquiring third-party funded projects, annual and financial reports Apr. 2016–Mar. 2018 Institute for German, European and International Medical Law, Public Health Law and Bioethics of the Universities of Heidelberg and Mannheim, Germany Co-Investigator Project: ClinhiPS – A Scientific, Ethical and Comparative Legal Analysis of the Clinical Application of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells in Germany and Austria; sponsored by the BMBF (German Federal Ministry of Education and Research); funds: 657,678.00 EUR Jan. -

Gifts to Duke Law- School Womble Family Members Make Gift

VOLUME 7 Contents 2 From the Dean 5 Forum 6 The Teaching Role of the Law Librarian/ Richard A. Danner 11 Health Care as a Laboratory for the Study of Law/ Clark C Havighurst 15 Intellectual Property Under the Constitution/ David L. Lange 19 About the School 20 Admissions: Enrolling the Best and the Brightest 28 BLSA Recruitment Conference DEAN EDITOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Pamela B. Gann Evelyn M. Pursley Janse Conover Haywood NUMBER 2 31 The Docket 32 Faculty Profile: Clark C. Havighurst, Health Law Expert 35 Alumnus Profile: Kenneth W. Starr '73, Solicitor General: Lawyer for the United States 40 Book Review: American Space Law: International and Domestic by Nathan C. Goldman '75 43 Specially Noted 52 Alumni Activities 59 Upcoming Events Duke Law Magazine is published under the auspices of the Office of the Dean, Duke University School of uw, Durham, North Carolina 27706 © Duke University 1989 SUPPORT SERVICES STUDENT CONTRIBUTORS PRODUCTION Mary Jane Flowers D.S. Berenson Graphic Arts Services Evelyn Holt-Fuller Ralph E. Jones Matthew W Sawchak DUKE LAW MAGAZINE I 2 From the Dean plinary backgrounds. They are also mature beyond his years. He is pres ently completing his Ph.D. in the Duke School of Divinity. He will hold a primary tenured appointment in the Law School and a secondary appointment in the Divinity School. Neil Vidmar is a social psychol ogist who joins us from the Uni versity of Western Ontario, Canada. Social scientists now play a central role in many of the top-ranked law schools. The appointment of Dr. Vidmar as a tenured member of our faculty recognizes that the Law School should have a social scien tist on its faculty in order to be a top research legal institution that also provides a professionally ade quate education for its students. -

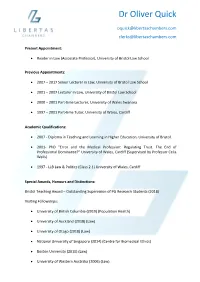

Dr Oliver Quick

Dr Oliver Quick [email protected] [email protected] Present Appointment: • Reader in Law (Associate Professor), University of Bristol Law School Previous Appointments: • 2007 – 2017 Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Bristol Law School • 2001 – 2007 Lecturer in Law, University of Bristol Law School • 2000 – 2001 Part-time Lecturer, University of Wales Swansea • 1997 – 2001 Part-time Tutor, University of Wales, Cardiff Academic Qualifications: • 2007 - DiPloma in Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, University of Bristol. • 2001- PhD “Error and the Medical Profession: Regulating Trust. The End of Professional Dominance?” University of Wales, Cardiff (SuPervised by Professor Celia Wells) • 1997 - LLB Law & Politics (Class 2.1) University of Wales, Cardiff Special Awards, Honours and Distinctions: Bristol Teaching Award – Outstanding SuPervision of PG Research Students (2018) Visiting FellowshiPs: • University of British Columbia (2019) (PoPulation Health) • University of Auckland (2018) (Law) • University of Otago (2018) (Law) • National University of Singapore (2014) (Centre for Biomedical Ethics) • Boston University (2010) (Law) • University of Western Australia (2006) (Law) Dr Oliver Quick [email protected] [email protected] RESEARCH OVERVIEW: My research is interdisciPlinary and imPactful, focusing on Professionalism, regulation, safety, technology and trust in healthcare. I have Published three books which have made major international contributions to scholarshiP in health law and criminal -

ABORTION, HUMAN RIGHTS and MEDICAL ADVANCES in DIGITAL AGE 10.36740/Wlek202101126

Wiadomości Lekarskie, VOLUME LXXIV, ISSUE 1, JANUARY 2021 © Aluna Publishing REVIEW ARTICLE ABORTION, HUMAN RIGHTS AND MEDICAL ADVANCES IN DIGITAL AGE 10.36740/WLek202101126 Yulia S. Razmetaeva, Olga O. Sydorenko DEPARTMENT OF THEORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF LAW, YAROSLAV MUDRYI NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, KHARKIV, UKRAINE ABSTRACT The aim: The article analyzes the impact of abortion on human rights and women’s health in the light of medical and technological advances of the digital age. Materials and methods: The methods of research were dialectic approach and general analysis of normative and scientific sources, analysis of the results of studies of women’s mental health after abortions, analysis of judicial practice, especially decisions of the European Court of Human Rights, the results of author’s own empirical studies, the formal legal method, the comparative legal method and the historical method. It has been established that there is no strong evidence that abortion negatively affects a woman’s mental health, including no evidence that the emotional consequences are deeply personal, or are rather the result of societal pressure. Arguments were refuted about extending the protection of human rights regarding abortion to unborn children and their fathers. Conclusions: The article emphasizes that the ethical burden on medical workers, especially in jurisdictions that require the approval of a doctor to legally terminate a pregnancy, increases significantly due to information flows and community expectations dictated by new medical advances. KEY WORDS: abortion, digital age, medical advances, human rights, reproductive health Wiad Lek. 2021;74(1):132-136 INTRODUCTION determine who we consider to be the owner of rights, to Medical ethics have traditionally received much attention, whom we give legal personality. -

Benjamin Mason Meier, JD, LLM

Benjamin Mason Meier, JD, LLM, PhD Department of Public Policy University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3435 919-962-0542 [email protected] / http://bmeier.web.unc.edu ACADEMIC Associate Professor, Department of Public Policy, University of North APPOINTMENTS Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2015-present Assistant Professor, Department of Public Policy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2009-2015 Zachary Taylor Smith Distinguished Term Associate Professor in Research and Undergraduate Education, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2016-2020 Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2015-present Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2009-2015 Scholar, O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, Georgetown University Law Center, 2009-present Visiting Assistant Professor, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, 2011-2012 EDUCATION Columbia University, Ph.D., Sociomedical Sciences, 2009 • Concentration and Qualifying Exams in Comparative Political Science and Global Public Health • Valedictory Speaker for Graduate School of Arts & Sciences Cornell Law School, LL.M., International and Comparative Law, cum laude, 2001 • Concentration in Human Rights • Institute of International and Comparative Law (Université de Paris I) Cornell Law School, J.D., cum laude, 2001 • -

Caregivers in Medical Law and Ethics

Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) Volume 25 Issue 1 Article 3 2008 Caregivers in Medical Law and Ethics Jonathan Herring Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp Recommended Citation Jonathan Herring, Caregivers in Medical Law and Ethics, 25 J. Contemp. Health L. & Pol'y 1 (2009). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp/vol25/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAREGIVERS IN MEDICAL LAW AND ETHICS Jonathan Herring* 1.INTRODUCTION Medical law and ethics is dominated by individualism. This is characterised by the clarion claims of many that I have the right to make decisions about my medical treatment; and that I should receive the treatment that is appropriate for me.' The problem with these questions is that, as Martha Minow pointed out, the question 'who is the patient?,' goes unasked.2 Unasked because many people think the answer is obvious: it is the person sitting in front of the doctor. One of the purposes of this article is to demonstrate that this is far too simplistic a response. 3 In medical law, as often in legal thought, the focus is on the image of an autonomous, competent man who can enforce his rights. In fact, we cannot separate our interests from those with whom we are in interdependent relationships.