Data Is Typically Not a Plural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

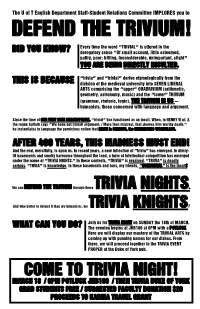

Defend the Trivium 11X17

The U of T English Department Staff-Student Relations Committee IMPLORES you to DEFEND THE TRIVIUM! Every time the word “TRIVIAL” is uttered in the DID YOU KNOW? derogatory sense “Of small account, little esteemed, paltry, poor; trifling, inconsiderable, unimportant, slight” YOU ARE BEING DIRECTLY INSULTED. “trivia” and “trivial” derive etymologically from the THIS IS BECAUSE division of the medieval university into SEVEN LIBERAL ARTS comprising the ”upper” QUADRIVIUM (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music) and the “lower” TRIVIUM (grammar, rhetoric, logic). THE TRIVIUM IS US — humanists, those concerned with language and argument. Since the time of OUR VERY OWN SHAKESPEARE, “trivial“ has functioned as an insult. When, in HENRY VI pt. 2, the rogue Suffolk says “We haue but triuiall argument, / More then mistrust, that shewes him worthy death,” he instantiates in language the pernicious notion that MATH is SERIOUS, the HUMANITIES WORTHLESS. AFTER 400 YEARS, THIS MADNESS MUST END! And the end, mercifully, is upon us. In recent years, a new inflection of “trivia” has emerged. In dimly- lit basements and smoky barrooms throughout the land, a form of intellectual competition has emerged under the name of “TRIVIA NIGHTS.” In these contests, “TRIVIA” is revalued. “TRIVIA” is deadly serious. “TRVIA” is knowledge. In these basements and bars, my friends, “QUADRIVIAL” is the insult! We can DEFEND THE TRIVIUM through these TRIVIA NIGHTS. And who better to defend it than we humanists, we TRIVIA KNIGHTS? Join us for TRIVIA NIGHT on SUNDAY the 18th of MARCH. WHAT CAN YOU DO? The evening begins at JHB100 at 6PM with a POTLUCK. Here we will display our mastery of the TRIVIAL ARTS by coming up with punning names for our dishes. -

2020-2021 Family Handbook for Trivium Prep

**Important Notice of Changes Due to COVID-19** Additional addendums have been included in sections marked with a red asterisk (*) of this handbook. (Academic Expectations, Evaluation and Student Promotion, Attendance, Illness and Tardiness, Behavior Code and Discipline, Student Social Life, Basic School Information, and Signature Page) TRIVIU PREPARATORY ACADEMY A Great Hearts Academy 2020 - 2021 FAMILY HANDBOOK LETTER TO FAMILIES ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 OUR MISSION ....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 OUR CHARTER, ACCREDITATION, AND AFFILIATIONS ........................................................................................ 7 TRIVIUM PREPARATORY ACADEMY’S PHILOSOPHY ............................................................................................ 8 KNOWLEDGE AND THE GREAT BOOKS .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 UPHOLDING STANDARDS .................................................................................................................................................................................. 10 MORAL VIRTUE ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

In Defense of a Liberal Education

In Defense of a Liberal Education FAREED ZAKARIA W. W. NORTON & COMPANY New York • London For my children, Omar, Lila, and Sofia We are drowning in information, while starving for wisdom. The world henceforth will be run by synthesizers, people able to put together the right information at the right time, think critically about it, and make important choices wisely. —E. O. Wilson Contents 1: Coming to America 2: A Brief History of Liberal Education 3: Learning to Think 4: The Natural Aristocracy 5: Knowledge and Power 6: In Defense of Today’s Youth Notes Acknowledgments In Defense of a Liberal Education 1 Coming to America IF YOU WANT to live a good life these days, you know what you’re supposed to do. Get into college but then drop out. Spend your days learning computer science and your nights coding. Start a technology company and take it public. That’s the new American dream. If you’re not quite that adventurous, you could major in electrical engineering. What you are not supposed to do is study the liberal arts. Around the world, the idea of a broad-based “liberal” education is closely tied to the United States and its great universities and colleges. But in America itself, a liberal education is out of favor. In an age defined by technology and globalization, everyone is talking about skills-based learning. Politicians, businesspeople, and even many educators see it as the only way for the nation to stay competitive. They urge students to stop dreaming and start thinking practically about the skills they will need in the workplace. -

The Crossings Newsletter Day

January 2019 January 2019 Nothing Trivial Dates To Remember It is a little-known fact that January 4 is Trivia The Crossings Newsletter Day. Ahh, trivia, which for many is considered Shopping Trips useless or trivial knowledge. But the word trivia has th The Crossings at Riverview Assisted Living 8451 US HWY 301 S. Riverview, FL 33578 813-465-0769 nothing to do with the useless or unimportant. Winn Dixie (7 ) * th Rather, it comes from the Latin word trivium, Target (14 ) which means “crossroads” or “place where three st roads meet.” From trivium came the word trivialis, Publix (21 ) meaning “found everywhere” or “commonplace.” Walmart In medieval times, the Trivium of academia referred to a threefold curriculum of grammar, logic, and rhetoric, as opposed to the Quadrivium of arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy. Wednesday Outings In fact, the Trivium was considered the essential nd Celebrating January foundation of a full liberal arts education as far Fred’s Market (2 ) back as in ancient Greece, as explained by Plato th Movie Theater Outing (9 ) Soup Month in his dialogues. As you can see, there is nothing th Leggings & Long Johns Month at all trivial about the Trivium or about the Moreno’s Bakery (16 ) Snowman Month meaning of the word trivia. rd Keke’s (23 ) Trivia Month th Creativity Month Researchers even argue that trivia games Brandon Mall (30 ) Football Fever Month are good for the brain. People enjoy guessing Glaucoma Awareness Month answers to questions about little-known facts. Reminiscence Month Psychology professor John Kouinos explains that Hobby Month your brain experiences a dopamine rush when getting the answer right. -

2021-2022 Family Handbook for Trivium Prep

TRIVIU PREPARATORY ACADEMY A Great Hearts Academy 2021 - 2022 FAMILY HANDBOOK LETTER TO FAMILIES ................................................................................................................................................ 5 OUR MISSION ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 OUR CHARTER, ACCREDITATION, AND AFFILIATIONS .................................................................................... 7 TRIVIUM PREPARATORY ACADEMY’S PHILOSOPHY ........................................................................................ 8 KNOWLEDGE AND THE GREAT BOOKS................................................................................................................................................. 8 UPHOLDING STANDARDS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 10 MORAL VIRTUE ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 10 COMMUNICATION ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 GREAT HEARTS CEO AND MANAGEMENT TEAM ........................................................................................................................... -

Arbor House News

January 2019 Arbor House News New Year, Lasting Traditions Another new year begins, and all around the world people will be popping champagne, singing “Auld Lang Syne,” and kissing loved ones at the stroke of midnight. But just why, exactly, do we repeat these New Year’s traditions year after year? Our Staff Christi Dobbs Bubbly champagne is the drink of choice on New Year’s. Its invention is Executive Director often credited to Dom Perignon, the Benedictine monk who oversaw the Marki Denton wine cellars of his abbey in the year 1697. While others saw bubbles as a Director of Nursing problematic sign that wine had spoiled, Perignon perfected the production of this new fermented drink known as champagne. From its beginnings in the Lillian “Lil” Kenney Admissions & Marketing Director abbey cellar, champagne was regularly used in religious celebrations such as consecrations and coronations. It then made the natural transition to Sarah Dixon secular celebrations, most notably at the soirees of the French aristocracy. As Dietary Supervisor champagne became cheaper and more accessible, it became the classiest bev- Katie Williams erage to offer during the holidays. Engagement Coordinator Scotland’s national poet Robert Burns penned the words to “Auld Lang Amber Hughes Wellness Coordinator Continued on page 4 Laura Tucker Administrative Assistant Shelley Jones RN Consultant Inside this issue: New Year, Lasting Tradi- 2 tions Bye-Bye to Dry 2 A life in Words 2 Nothing Trivial 3 Burst Your Bubble 3 Birthdays 4 Mission 4 Page 2 Bye-Bye to Dry Nothing Trivial The cold, dry winter air can wreak havoc on sensitive It is a little-known fact that Jan. -

The Embedded Skills Within a Liberal Arts Education – the Key to Future Success Debra Pitton, April 25, 2019

Wahlstrom Lecture: The embedded skills within a liberal arts education – the key to future success Debra Pitton, April 25, 2019 I want to thank those who nominated me for this opportunity. It is an honor to speak to you all tonight. I have titled this talk, “The embedded skills within a liberal arts education – the key to future success.” As the Wahlstrom Lecture was initiated to provide ideas regarding Liberal Arts in the 21st Century, zeroing in on the skills that students gain from a liberal arts education is where I will focus my comments. All of you here are most likely familiar with what it means when we talk about the liberal arts. However, I have been in situations when I realize that not everyone is clear about what we mean by liberal arts. I was attending a meeting in my community about a school referendum, and someone near me was going on about how their child wanted to go off to a liberal arts college, but the parent was not in favor of sending their child to a liberal institution. They said they didn’t want the ideas and values they had instilled into their children to be eroded by studying at a liberal college. As it was not appropriate for me at that time to provide clarification, I bit my tongue and turned back into the meeting. However, I wondered how many other parents held this viewpoint. So not to take anything for granted, and as this is a lecture about liberal arts – I feel obligated to ensure you know a bit about where the concept came from and what it entails .