Volume 40 1.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judges' Annual Report

Supreme Court of Victoria 2002–04 Annual Report SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA 2002–04 JUDGES’ ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS LETTER TO THE GOVERNOR Court Profile 1 To His Excellency Year at a Glance 2 The Honourable John Landy, AC, MBE Report of the Chief Justice 3 Governor of the State of Victoria and its Chief Executive Officer’s Review 7 Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia Court of Appeal 10 Dear Governor Trial Division: Civil 13 We, the Judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria have the honour to present our Annual Report Trial Division: Commercial and Equity 18 pursuant to the provisions of the Supreme Court Act 1986 with respect to the financial years of Trial Division: Common Law 22 1 July 2002 to 30 June 2003 and 1 July 2003 to 30 June 2004, including a transitional 18-month Trial Division: Criminal 24 Judges’ Report, reflecting the change in reporting period from calendar year to financial year. Masters 26 Funds in Court 29 Court Governance 31 Yours sincerely Judicial Organisational Chart 33 Judicial Administration 34 Court Management 36 Service Delivery 37 The Victorian Jury System 40 Marilyn L Warren The Court’s People 42 Chief Justice of Victoria Community Access 43 10 May 2005 Finance Report 2002–03 and 2003–04 45 Senior Master’s Special Purpose Financial Report for the John Winneke, P P D Cummins, J D J Habersberger, J Year Ended 30 June 2003 50 W F Ormiston, J A T H Smith, J R S Osborn, J Senior Master’s Special Purpose Stephen Charles, J A David Ashley, J J A Dodds-Streeton, J Financial Report for the F H Callaway, J A John -

SPECIAL Victoria Government Gazette

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 115 Friday 8 April 2011 By Authority of Victorian Government Printer COMMISSION passed under the Royal Sign Manual and the Public Seal of the State of Victoria appointing THE HONOURABLE MR ALEX CHERNOV AO QC to be the Governor of the State of Victoria in the Commonwealth of Australia ELIZABETH THE SECOND, by the Grace of God Queen of Australia and Her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth: To the Honourable Mr Alex Chernov AO QC Greeting: We hereby appoint you Alex Chernov, under section 6(2) of the Constitution Act 1975 of the State of Victoria to be, during Our Pleasure, Our Governor of Our State of Victoria, in the Commonwealth of Australia. AND WE hereby authorise, empower and command you to perform the powers and functions of the Office of Governor in accordance with the Constitution Act 1975 of the State of Victoria, the Australia Acts 1986 of the Commonwealth of Australia and of the United Kingdom, and all other applicable laws. AND this Commission shall supersede our Commission dated 14 March 2006 appointing Professor David de Kretser AC, to be Governor of Our State of Victoria on 8 April 2011 or, if you have not taken the prescribed Oaths or Affirmations before that date, as soon as you have taken those Oaths or Affirmations. AND we hereby command all our subjects in Our State of Victoria and all other persons who may lawfully be required to do so to give due respect and obedience to the Governor accordingly. Given at Our Court of Saint James’s on 1 March 2011 By Her Majesty’s Command, (L.S.) TED BAILLIEU Premier of Victoria COMMISSION appointing the Honourable Mr Alex Chernov AO QC to be Governor of the State of Victoria SPECIAL 2 S 115 8 April 2011 Victoria Government Gazette PROCLAMATION By His Excellency, Alex Chernov, Governor of the State of Victoria in the Commonwealth of Australia. -

Deakin Law Review Style Guide

ACHIEVING THE AIMS OF OPEN JUSTICE? THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE COURTS, THE MEDIA AND THE PUBLIC ∗ SHARON RODRICK This article begins by outlining what the principle of open justice is intended to achieve. It then investigates the nature of the relationship that exists between the courts and the media, and between the media and the public, and suggests that these relationships are not always conducive to realising the aims of open justice. While the reporting role of the traditional news media will undoubtedly persist, at least for the foreseeable future, it is argued that, since courts now have the means to deliver to the public a fuller and truer picture of their work than the media can, they should seize the opportunity to do so. I INTRODUCTION Open justice is a utilitarian concept and is a means to an end, but not an end in itself.1 The chief object of courts is not to be open and accessible, but to ensure that justice is done according to law.2 In Re Hogan; Ex parte West Australian Newspapers Ltd, the Western Australian Court of Appeal decried the ‘tendency to identify the principle of open justice as the ultimate object, divorced from the rationale for its existence’.3 With that caution in mind, the first part of this article will outline what the principle of open justice is intended to achieve. The remainder of the article will examine how the courts (the object and focus of the principle), the media (the primary channel through * BA, LLB (Hons) (Melb), LLM (Melb), Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Monash University. -

The Supreme Court of Victoria

ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL Annual Report Supreme Court a SUPREME COURTSUPREME OF VICTORIA 2016-17 of Victoria SUPREME COURTSUPREME OF VICTORIA ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17ANNUAL Supreme Court Annual Report of Victoria 2016-17 Letter to the Governor September 2017 To Her Excellency Linda Dessau AC, Governor of the state of Victoria and its Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia. Dear Governor, We, the judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria, have the honour of presenting our Annual Report pursuant to the provisions of the Supreme Court Act 1986 with respect to the financial year 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017. Yours sincerely, Marilyn L Warren AC The Honourable Chief Justice Supreme Court of Victoria Published by the Supreme Court of Victoria Melbourne, Victoria, Australia September 2017 © Supreme Court of Victoria ISSN 1839-6062 Authorised by the Supreme Court of Victoria. This report is also published on the Court’s website: www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au Enquiries Supreme Court of Victoria 210 William Street Melbourne VIC 3000 Tel: 03 9603 6111 Email: [email protected] Annual Report Supreme Court 1 2016-17 of Victoria Contents Chief Justice foreword 2 Court Administration 49 Discrete administrative functions 55 Chief Executive Officer foreword 4 Appendices 61 Financial report 62 At a glance 5 Judicial officers of the Supreme Court of Victoria 63 About the Supreme Court of Victoria 6 2016-17 The work of the Court 7 Judicial activity 65 Contacts and locations 83 The year in review 13 Significant events 14 Work of the Supreme Court 18 The Court of Appeal 19 Trial Division – Commercial Court 23 Trial Division – Common Law 30 Trial Division – Criminal 40 Trial Division – Judicial Mediation 45 Trial Division – Costs Court 45 2 Supreme Court Annual Report of Victoria 2016-17 Chief Justice foreword It is a pleasure to present the Annual Report of the Supreme Court of Victoria for 2016-17. -

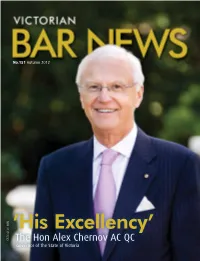

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

Should Judges Be Mediators? the Hon Marilyn Warren AC*

Should judges be mediators? The Hon Marilyn Warren AC* This article was originally presented by Chief Justice Warren at the Supreme and Federal Court Judges’ Conference in 2010. In it, her Honour advocates the pursuit of direct judicial involvement in alternative dispute resolution, but rejects the proposal that judges should act as mediators. Her Honour’s primary concern is to protect the integrity of the judicial role from actual or perceived dilution. “Should judges be mediators?” Another way to ask the question is: “The role of judges and courts – is it changing and should it?” Any discussion needs to look first at where litigation has come from, and where it seems to be heading. Twenty-five years or so ago, mediation as a feature of the court system was unknown. Cases were fought, won and lost in the courtroom, with a fair few settling after some argy bargy at the court door. The ancient concept of mediation, well practised by the Chinese for millennia, was viewed as foreign. The overarching concept of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) was unheard of. Arbitration was something peculiar to the construction sector. Driven by the pressures of burgeoning court lists, interminable delays, and long, complex litigation, the courts called for more judges. Governments would not have a bar of it. I recall, as a government lawyer, sitting in on a deputation of the chairperson of the Victorian Bar and very senior barristers to the Attorney-General. The Attorney-General told the deputation very directly that no new judges would be appointed; the problem of delays in courts had to be solved by tackling the court process itself. -

Extract from Book

EXTRACT FROM BOOK PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Tuesday, 14 September 2010 (Extract from book 14) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier, Minister for Veterans’ Affairs and Minister for Multicultural Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Deputy Premier, Attorney-General and Minister for Racing............ The Hon. R. J. Hulls, MP Treasurer, Minister for Information and Communication Technology, and Minister for Financial Services.............................. The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Regional and Rural Development, and Minister for Industry and Trade............................................. The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Health............................................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Minister for Energy and Resources, and Minister for the Arts........... The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services, and Minister for Corrections................................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Community Development.............................. The Hon. L. D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Small Business.............. The Hon. J. Helper, MP Minister for Finance, WorkCover and the Transport Accident Commission, -

Supreme Court of Victoria 2007–2008 Annual Report Contents

Supreme Court of Victoria 2007–2008 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Chief Justice’s report 2 Who we are – an overview 3 The Court of Appeal 4 The Trial Division 4 Judges and Masters 5 What we do – our year in review 6 The Court of Appeal 7 The Trial Division 10 Report of the Masters 23 Senior Master’s LETTER TO THE GOVERNOR (Funds in Court) Office 25 June 2009 Reports from To His Excellency Professor David de Kretser AC the wider Court 27 Governor of the State of Victoria and its Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia Judicial Training 28 Dear Governor Court Administration 29 We, the Judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria have the honour to present Supreme Court our Annual Report pursuant to the provisions of the Supreme Court Act 1986 Registry 30 with respect to the financial year of 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2008. Juries Commissioner 33 Yours sincerely Library 34 Board of Examiners 34 Adult Parole Board 35 Marilyn L Warren AC Forensic Leave Panel 35 Chief Justice of Victoria Finance report 36 C Maxwell, P D Byrne, J K W S Hargrave, J P Buchanan, J A D L Harper, J B J King, J Glossary 37 F H R Vincent, J A H R Hansen, J A L Cavanough, J G A A Nettle, J A P Mandie, J E H Curtain, J Appendix 39 D J Ashley, J A B D Bongiorno, J G Pagone, J M A Neave, J A D J Habersberger, J P Coghlan, J Judicial activity 39 R F Redlich, J A R S Osborn, J R Robson, J M B Kellam, J A K M Williams, J J Forrest, J J A Dodds-Streeton, J A S Kaye, J L Lasry, J M Weinberg, J A S Whelan, J P Vickery, J P D Cummins, J E Hollingworth, J E Kyrou, J T H Smith, J K H Bell, -

Open Justice in the Technological Age*

OPEN JUSTICE IN THE TECHNOLOGICAL AGE* THE HON CHIEF JUSTICE MARILYN WARREN AC** This speech explores the role of open justice in a new technological age. While courts have been public places for centuries, the advent of new technologies and social media has driven courts towards direct community engagement in order to preserve open justice. The reduction in official press reporting of court cases has meant there is an information vacuum that is being filled through social media and online content. This phenomenon results in information being published without deference to editorial opinion regarding its newsworthiness or the accuracy of content. The proliferation of online commentary has the potential to undermine the right to a fair trial for many. While courts must continue to be vigilant in ensuring certain information is suppressed in some cases, it must also engage with social media to ensure open justice. The Supreme Court of Victoria has a presence on Twitter and Facebook and may soon pilot a project where a retired Supreme Court judge would blog on certain legal issues. These are all steps to ensure that the Supreme Court continues to safeguard open justice in a new technological paradigm. I INTRODUCTION The concept that ‘justice must be done and must be seen to be done’ is a fundamental tenet of Australian democracy. Historically, this meant that most courtrooms, most of the time, were open to the public. In reality, for most of the last half century, relatively few members of the public have used that open door and court reporters have acted as the intermediary between the justice system and the wider community. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Thursday, 17 September 2009 (Extract from book 12) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier, Minister for Veterans’ Affairs and Minister for Multicultural Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Deputy Premier, Attorney-General and Minister for Racing............ The Hon. R. J. Hulls, MP Treasurer, Minister for Information and Communication Technology, and The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Financial Services.................................. Minister for Regional and Rural Development, and Minister for Skills and Workforce Participation............................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Health............................................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Minister for Community Development and Minister for Energy and Resources.................................................... The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services, and Minister for Corrections................................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Small Business.............. The Hon. J. Helper, MP Minister for Finance, WorkCover and the Transport Accident Commission, Minister for Water and Minister for Tourism -

What Is Justice?

What is justice? Remarks of the Hon. Marilyn Warren AC Chief Justice of Victoria 2014 Newman Lecture Mannix College Wednesday 20 August 2014 Introduction In her exquisite story To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee looks at justice through the eyes of a child living in a small American town where segregation, discrimination and poverty are the norm. Striding through layers of social under-privilege contrasted with comfortable privilege is the powerful, emblematic figure of Atticus Finch. Yet, even he is vulnerable in his courageous commitment to justice when a lynch mob arrives to take his client, a black man falsely accused of rape. Atticus is saved by the perceptive and penetrating innocence of the child Scout who stands appealingly in the circle of men and pleads for their kindness - a vehicle for justice. So, the mob disperses, the story continues to its climactic conclusion where justice is defeated in a way that is most unexpected. Life then proceeds, mostly as normal, yet differently. Harper Lee familiarises the reader with justice through a vivid description of injustice. 1 So let us explore the question. What is justice? For different people at different times it means different things. To the ordinary person ‘justice’ will often mean due punishment when a criminal is sentenced for a crime. To the popular media ‘justice’ will generally mean harsh punishment primarily focused on strong retribution and deterrence. Then there is a notion of social justice to be compared with legal justice. The basic needs of humanity – shelter, education and healthcare – are sometimes advocated on the basis of a fundamental humane entitlement. -

Victoria Government Gazette No

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 141 Tuesday 16 April 2013 By Authority of Victorian Government Printer Corrections Amendment Act 2013 PROCLAMATION OF COMMENCEMENT I, Marilyn Warren, Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria, as the Governor’s Deputy, with the advice of the Executive Council and under section 2(1) of the Corrections Amendment Act 2013, fix 30 April 2013 as the day on which that Act (except sections 4(2), 5, 6, 7, 20, 21 and 36(2)) comes into operation. Given under my hand and the seal of Victoria on 16th April 2013 (L.S.) MARILYN WARREN Lieutenant-Governor, as the Governor’s Deputy By His Excellency’s Command ANDREW MCINTOSH Minister for Corrections Justice Legislation Amendment (Cancellation of Parole and Other Matters) Act 2013 PROCLAMATION OF COMMENCEMENT I, Marilyn Warren, Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria, as the Governor’s Deputy, with the advice of the Executive Council and under section 2(2) of the Justice Legislation Amendment (Cancellation of Parole and Other Matters) Act 2013, fix 20 May 2013 as the day on which the remaining provisions of that Act come into operation. Given under my hand and the seal of Victoria on 16th April 2013 (L.S.) MARILYN WARREN Lieutenant-Governor, As the Governor’s Deputy By His Excellency’s Command ANDREW MCINTOSH Minister for Corrections Courts Legislation Amendment (Reserve Judicial Officers) Act 2013 PROCLAMATION OF COMMENCEMENT I, Marilyn Warren, Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria, as the Governor’s Deputy, with the advice of the Executive Council and under section 2(2) of the Courts Legislation Amendment (Reserve Judicial Officers) Act 2013, fix 17 April 2013 as the day on which the sections 62, 63 and 64 of that Act come into operation.