WAS There a Particular Social Behaviour and Manner of Life of Wirral Folk, That Distinguished Them Clearly from the People North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION for ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW of CHESHIRE WEST and CHESTER Draft Recommendations For

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF CHESHIRE WEST AND CHESTER Draft recommendations for ward boundaries in the borough of Cheshire West and Chester August 2017 Sheet 1 of 1 ANTROBUS CP This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2017. WHITLEY CP SUTTON WEAVER CP Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information NETHERPOOL applied as part of this review. DUTTON MARBURY ASTON CP GREAT WILLASTON WESTMINSTER CP FRODSHAM BUDWORTH CP & THORNTON COMBERBACH NESTON CP CP INCE LITTLE CP LEIGH CP MARSTON LEDSHAM GREAT OVERPOOL NESTON & SUTTON CP & MANOR & GRANGE HELSBY ANDERTON PARKGATE WITH WINCHAM MARBURY CP WOLVERHAM HELSBY ACTON CP ELTON CP S BRIDGE CP T WHITBY KINGSLEY LOSTOCK R CP BARNTON & A GROVES LEDSHAM CP GRALAM CP S W LITTLE CP U CP B T E STANNEY CP T O R R N Y CROWTON WHITBY NORTHWICH CP G NORTHWICH HEATH WINNINGTON THORNTON-LE-MOORS D WITTON U ALVANLEY WEAVERHAM STOAK CP A N NORTHWICH NETHER N H CP CP F CAPENHURST CP D A WEAVER & CP PEOVER CP H M CP - CUDDINGTON A O D PUDDINGTON P N S C RUDHEATH - CP F T O H R E NORLEY RUDHEATH LACH CROUGHTON D - H NORTHWICH B CP CP DENNIS CP SAUGHALL & L CP ELTON & C I MANLEY -

S Cheshire Oaks

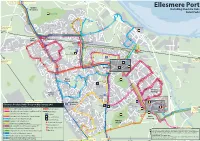

Cheshire West & Chester Council Ellesmere Port Area Destination Finder/Map 272 Hooton/Neston 272 M53 1 to Birkenhead/Liverpool 1 X1 2 to Brombrough/Liverpool N M53 ort 359 from Neston High Sch 359CHESTER ROAD h R B5132 o M53 ad B5132 S Childer Ellesmere Port ch oo l (including Cheshire Oaks L a Thornton n Rivacre Road e d Poole Hall Road oa R a ll e ) a r Retail Park) L c d d Rivacre Valley H (M53) r a a d 8 a h oo le t P a o rc od c Country Park o R O o n R u h W J l s Manchester Ship Canal l o e o p W r ( Hillside Drive e 7 River Mersey 0 h NAYLOR RD 7 t 5 vale ss e 5 o N A M Warren Drive Rothe RIVACRE BROW 7 W r F H a D MERSEYTON RD 1 X1 Hillfield Road i 7 r e rw h iv a a a e 272 d ys r t 359 f M53 h a e D e CHESTER ROAD o r R n L L Sweetfiel iv 7 a d G a T ds s e a ld HILLSIDE DRIVE ne e r L y n National fi u t a es ROSSMORE RD EAST e n n r e m Fo e o r w Trains to Hooton/ i Waterways G a d L n Pou nd Road P n n i s n d Museum Birkenhead/ A l a e W Grosvenor Road L an n e R 7 Liverpool t 7 a Ave Rossbank Road t Dock St QUEEN STREET RIVACRE ROAD Station ion Dr Ch es d ter a Livingstone Road Rd o R ROSSMORE ROAD EAST ROSSMORE ROAD WEST X1 7 d l 7 O e i OVERPOOL RD Bailey Avenue l 106 S fi S Woodend Rd s i s Percival Rd t Berwick Road H CHESTER ROAD e Little Ferguson Ave Crossley o JohnGrace St Rd s i R l Straker Avenue e R l o c Ave v WESTMINSTER RD a i S r eym d r Little Sutton our e Sutton Drive D s t 106 S k R Station r o a C a 6 HAWTHORNE ROAD Overpool Wilkinson St P l d e 359LEDSHAM ROAD v m e Overpool e a 6 Rd 1 6 GLENWOOD ROAD Av -

THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE for ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW of CHESHIRE WEST and CHESTER Draft Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in Th

SHEET 3, MAP 3 Proposed Ward boundaries in Willaston, Burton and Thornton KEY THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND UNITARY AUTHORITY BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY ELECTORAL REVIEW OF CHESHIRE WEST AND CHESTER PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY WEST SUTTON WARD PROPOSED WARD NAME Draft Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in the Unitary Authority of Cheshire West and Chester November 2009 LEDSHAM CP PARISH NAME Sheet 3 of 7 NESTON PARISH WARD PROPOSED PARISH WARD NAME Scale : 1cm = 0.08000 km This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Grid interval 1km Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Electoral Commission GD03114G 2009. Glenmoriston Home Farm E K A R M A H T S N A E B E W E N C T H Y E H S E T A E T R H R L O A N A E D H S OOT T ON R G S REE C E N H E T B 51 O 53 O H Hooton Works E L Y Trading Estate L A L N A Woodside N E B E Nursery E 5 N 1 5 A 1 D L Greenwood ROA TON L HOO L Nurseries Chestnut E NESTON WARD B Farm E ANE U ILL L L M B NESTON PARISH WARD Hinderton E B Mill Lane Farm N I A Grange R Church Hooton L K L E Hooton O N S O H Station C H E H C O S D A OA O RY R D W AR L E QU R L N O E O A A N V N D A E E L R L D L W I A D L A A M O E T R R LE OAD E A O R R Recreation Ground D TON R A W IA OO R D H B O A R H 54 ANN K S S 0 HAL Childer Thornton L ROA L D Willaston -

THE ANCIENT BOKOUGH of OVER, CHESHIRE. by Thomas Rigby Esq

THE ANCIENT BOKOUGH OF OVER, CHESHIRE. By Thomas Rigby Esq. (RsiD IST DECEMBER, 1864.J ALMOST every village has some little history of interest attached to it. Almost every country nook has its old church, round which moss-grown gravestones are clustered, where The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep. These lithic records tell us who lived and loved and laboured at the world's work long, long ago. Almost every line of railroad passes some ivy-mantled ruin that, in its prime, had armed men thronging on its embattled walls. Old halls, amid older trees old thatched cottages, with their narrow windows, are mutely eloquent of the past. The stories our grandfathers believed in, we only smile at; but we reverence the spinning wheel, the lace cushion, the burnished pewter plates, the carved high-backed chairs, the spindle-legged tables, the wainscoted walls and cosy " ingle nooks." Hath not each its narrative ? These are all interesting objects of the bygone time, and a story might be made from every one of them, could we know where to look for it. With this feeling I have undertaken to say a few words about the ancient borough of Over in Cheshire, where I reside; and, although the notes I have collected may not be specially remarkable, they may perhaps assist some more able writer to complete a record of more importance. Over is a small towu, nearly in the centre of Cheshire. It consists of one long street, crossed at right angles by Over u Lane, which stretches as far as Winsford, and is distant about two miles from the Winsford station on the London and North-Western Railway. -

Wirral Peninsula Group Visits & Travel Trade Guide 2013/2014

Wirral Peninsula Group Visits & Travel Trade Guide 2013/2014 www.visitwirral.com C o n t e n t s Contents Wirral Peninsula 05 itineraries 07 Wirral tourism ProduCt 21 - a ttraCtions 22 - a CCommodation 28 - e vents 30 - F ood & d rink 31 CoaCh inFormation 37 Cover images (from left to right): Wirral Food & Drink Festival, Ness Botanic Gardens, Mersey Ferry, Port Sunlight The businesses and organisations listed in this guide are not an exhaustive list but are those that we know to be interested in the 03 Group Travel market and hence will be receptive to enquiries. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy in this publication, Wirral Council cannot accept responsibility for any errors, inaccuracies or omissions. View from Sheldrakes Restaurant, Lower Heswall W i r r a l P e n i n s u l Wirral Peninsula a Wirral Peninsula is tailor-made for groups and still retains an element of waiting to be discovered. Compact with fantastic, award-winning natural assets, including 35 miles of stunning coastline and an interior that surprises and delights, with pretty villages and rolling fields, a trip to Wirral never disappoints. Many of our attractions are free and many offer added extras for visiting groups and coach drivers. Wirral is well-connected to the national road network and is sandwiched between the two world-class cities of Liverpool and Chester, making it a perfect choice for combining city, coast and countryside whether on a day visit or a short break. The choice and quality of accommodation continues to grow while the local micro-climate ensures that the fresh food produced is of the highest quality and is served in many of our eateries. -

Youth Arts Audit: West Cheshire and Chester: Including Districts of Chester, Ellesmere Port and Neston and Vale Royal 2008

YOUTH ARTS AUDIT: WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER: INCLUDING DISTRICTS OF CHESTER, ELLESMERE PORT AND NESTON AND VALE ROYAL 2008 This project is part of a wider pan Cheshire audit of youth arts supported by Arts Council England-North West and Cheshire County Council Angela Chappell; Strategic Development Officer (Arts & Young People) Chester Performs; 55-57 Watergate Row South, Chester, CH1 2LE Email: [email protected] Tel: 01244 409113 Fax: 01244 401697 Website: www.chesterperforms.com 1 YOUTH ARTS AUDIT: WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER JANUARY-SUMMER 2008 CONTENTS PAGES 1 - 2. FOREWORD PAGES 3 – 4. WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER PAGES 3 - 18. CHESTER PAGES 19 – 33. ELLESMERE PORT & NESTON PAGES 34 – 55. VALE ROYAL INTRODUCTION 2 This document details Youth arts activity and organisations in West Cheshire and Chester is presented in this document on a district-by-district basis. This project is part of a wider pan Cheshire audit of youth arts including; a separate document also for East Cheshire, a sub-regional and county wide audit in Cheshire as well as a report analysis recommendations for youth arts for the future. This also precedes the new structure of Cheshire’s two county unitary authorities following LGR into East and West Cheshire and Chester, which will come into being in April 2009 An audit of this kind will never be fully accurate, comprehensive and up-to-date. Some data will be out-of-date or incorrect as soon as it’s printed or written, and we apologise for any errors or omissions. The youth arts audit aims to produce a snapshot of the activity that takes place in West Cheshire provided by the many arts, culture and youth organisations based in the county in the spring and summer of 2008– we hope it is a fair and balanced picture, giving a reasonable impression of the scale and scope of youth arts activities, organisations and opportunities – but it is not entirely exhaustive and does not claim to be. -

Wirral Archives Service Workshop Medieval Wirral (11Th to 15Th Centuries)

Wirral Archives Service Workshop Medieval Wirral (11th to 15th centuries) The Norman Conquest The Norman Conquest was followed by rebellions in the north. In the summer of 1069 Norman armies laid waste to Yorkshire and Northumbria, and then crossed the Pennines into Cheshire where a rebellion had broken out in the autumn – they devastated the eastern lowlands, especially Macclesfield, and then moved on to Chester, which was ‘greatly wasted’ according to Domesday Book – the number of houses paying tax had been reduced from 487 to 282 (by 42 per cent). The Wirral too has a line of wasted manors running through the middle of the peninsula. Frequently the tax valuations for 1086 in the Domesday Book are only a fraction of that for 1066. Castles After the occupation of Chester in 1070 William built a motte and bailey castle next to the city, which was rebuilt in stone in the twelfth century and became the major royal castle in the region. The walls of Chester were reconstructed in the twelfth century. Other castles were built across Cheshire, as military strongholds and as headquarters for local administration and the management of landed estates. Many were small and temporary motte and bailey castles, while the more important were rebuilt in stone, e.g. at Halton and Frodsham [?] . The castle at Shotwick, originally on the Dee estuary, protecting a quay which was an embarkation point for Ireland and a ford across the Dee sands. Beeston castle, built on a huge crag over the plain, was built in 1220 by the earl of Chester, Ranulf de Blondeville. -

Historic Towns of Cheshire

ImagesImages courtesycourtesy of:of: CatalystCheshire Science County Discovery Council Centre Chester CityCheshire Council County Archaeological Council Service EnglishCheshire Heritage and Chester Photographic Archives Library and The Grosvenor Museum,Local Studies Chester City Council EnglishIllustrations Heritage Photographic by Dai Owen Library Greenalls Group PLC Macclesfield Museums Trust The Middlewich Project Warrington Museums, Libraries and Archives Manors, HistoricMoats and Towns of Cheshire OrdnanceOrdnance Survey Survey StatementStatement ofof PurposePurpose Monasteries TheThe Ordnance Ordnance Survey Survey mapping mapping within within this this documentdocument is is provided provided by by Cheshire Cheshire County County CouncilCouncil under under licence licence from from the the Ordnance Ordnance Survey.Survey. It It is is intended intended to to show show the the distribution distribution HistoricMedieval towns ofof archaeological archaeological sites sites in in order order to to fulfil fulfil its its 84 publicpublic function function to to make make available available Council Council held held publicpublic domain domain information. information. Persons Persons viewing viewing thisthis mapping mapping should should contact contact Ordnance Ordnance Survey Survey CopyrightCopyright for for advice advice where where they they wish wish to to licencelicence Ordnance Ordnance Survey Survey mapping/map mapping/map data data forfor their their own own use. use. The The OS OS web web site site can can be be foundfound at at www.ordsvy.gov.uk www.ordsvy.gov.uk Historic Towns of Cheshire The Roman origin of the Some of Cheshire’s towns have centres of industry within a ancient city of Chester is well been in existence since Roman few decades. They include known, but there is also an times, changing and adapting Roman saltmaking settlements, amazing variety of other over hundreds of years. -

Brindley Archer Aug 2011

William de Brundeley, his brother Hugh de Brundeley and their grandfather John de Brundeley I first discovered William and Hugh (Huchen) Brindley in a book, The Visitation of Cheshire, 1580.1 The visitations contained a collection of pedigrees of families with the right to bear arms. This book detailed the Brindley family back to John Brindley who was born c. 1320, I wanted to find out more! Fortunately, I worked alongside Allan Harley who was from a later Medieval re-enactment group, the ‘Beaufort companye’.2 I asked if his researchers had come across any Brundeley or Brundeleghs, (Medieval, Brindley). He was able to tell me of the soldier database and how he had come across William and Hugh (Huchen) Brundeley, archers. I wondered how I could find out more about these men. The database gave many clues including who their captain was, their commander, the year of service, the type of service and in which country they were campaigning. First Captain Nature of De Surname Rank Commander Year Reference Name Name Activity Buckingham, Calveley, Thomas of 1380- Exped TNA William de Brundeley Archer Hugh, Sir Woodstock, 1381 France E101/39/9 earl of Buckingham, Calveley, Thomas of 1380- Exped TNA Huchen de Brundeley Archer Hugh, Sir Woodstock, 1381 France E101/39/9 earl of According to the medieval soldier database (above), the brothers went to France in 1380-1381 with their Captain, Sir Hugh Calveley as part of the army led by the earl of Buckingham. We can speculate that William and Hugh would have had great respect for Sir Hugh, as he had been described as, ‘a giant of a man, with projecting cheek bones, a receding hair line, red hair and long teeth’.3 It appears that he was a larger than life character and garnered much hyperbole such as having a large appetite, eating as much as four men and drinking as much as ten. -

Ellesmere Port Area Map January 2011 (09.01.11

272 272/274 Neston/Arrowe Park 274 401 401/X11 to Birkenhead/Liverpool M53 1 to Birkenhead/Liverpool 1 X11 N CHESTER ROAD M53 or th Ro B5132 ad M53 B5132 Ellesmere Port Schoo Childer l L (including Cheshire Oaks ane Thornton Rivacre Road d Poole Hall Road oa La R ll Retail Park) Rivacre Valley a cre ard La H a (M53) h Poo le d 8 c ad Country Park o ct Or o o n W R u l J Manchester Ship Canal poo r 7 7 Hillside Drive (Welsh Road) e River Mersey h NAYLOR RD 7S 7S vale oss M Net A550 7 Warren Drive 7S Rothe F RIVACRE BROW W r D H a MERSEYTON RD 1 401 Hillfield Road i 3 7 r r i v ea w 7S h 272 a a e ys rf th L 274X11 d D M53 CHESTER ROAD a r e Ro Sw iv 3 L eet e a ne field Gd a d T s HILLSIDE DRIVE l a s ne r ne fie u y est Road ROSSMORE RD EAST n m a r ee L n Fo r w Trains to Hooton/ a o Ellesmere Port G i lose d n Pound C 7 Road n P L s n Birkenhead/ l 7S d A a Grosvenor Road Boat Museum L e an n e Win R Liverpool t 7 RIVACRE ROAD a Ave t 7S Rossbank Road Dock St QUEEN STREET Station io C n Dr heste r d Livingstone Road Rd 272 a 274 o R 7 7 ROSSMORE ROAD WEST ROSSMORE ROAD EAST 7S 401 7S d l O OVERPOOL RD e i Bailey Avenue i l CHESTER ROAD S 106 f Si Ferguson Av Woodend Rd s t e Crossley s Percival Rd Berwick Road H e Ave o JohnGrace St Rd s il Straker Avenue R R l o c Little 7 ad res Seymour ve Little Sutton Drive WESTMINSTER RD t R Sutton Station 106 S o a Cl HAWTHORNE ROAD ark Dri d S 6 Overpool WILKINSON ST e ive Dr LEDSHAM ROAD Overpool v 6 e el Rd 1 6 X11 Av 272 and n Hillcrest to Black Lion Lane GLENWOOD edarROAD Station 3 401274 -

Ellesmere Port from Nantwich | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Ellesmere Port from Nantwich Cruise this route from : Nantwich View the latest version of this pdf Ellesmere-Port-from-Nantwich-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 5.00 to 0.00 Cruising Time : 24.00 Total Distance : 54.00 Number of Locks : 28 Number of Tunnels : 0 Number of Aqueducts : 0 Lovely cruise through the Cheshire Countryside to visit the Roman City of Chester and Ellesmere Port. There is a wealth of things to do in this Roman City which can be seen on foot, because of the amazing survival of the old city wall. You can walk right round Chester on this superb footpath. Chester Roman Amphitheatre is the largest in Britain, used for entertainment and military training by the 20th Legion, based at the fortress of 'Deva' (Chester).Discover 1,000 of shops behind the façades of the black and white buildings, find high street brands to designer boutiques. Shop in Chester's Rows where 21st century stores thrive in a Medieval setting. Take home some Cheshire cheese which is one of the oldest recorded cheeses in British history and is even referred to in the Domesday Book. Lying outside the town is Chester Zoo is home to 7000 animals including some of the most endangered species on the planet. In Ellesmere Port part of the old Dock complex is home to the Boat Museum. Exhibits, models and photos trace the development of the canal system from early time to its heyday in the 19th century. -

Cheshire. (Kelly's '

164 BOSLEY. CHESHIRE. (KELLY'S ' • • and reseated in 1878 and affords 250 sittings. The regis- tains 3,077 acres of land and 120 of water, all the property ters date from the· year 1728. T.he living is a: viea.rage, of the Earl of Harrington, who is lord of the manor. Rate .. gross yearly value £92, net £go, with 35 acres of glebe and able value, £4,885; th.e population in 1891 was 364. residence, in the gift of the vicar of Prestbury, and held Sexton and Clerk, Joseiph Cheetham. since l'891 by the Rev. George Edward. O'Brien M.A. of Post Office. Joseph Cheetbam, sub-postmaster. Letters Queen's College, Oxford. The Wesleyan school-room, arrive from Congleton at ·8.55 a.m.; dispatched thereto built in 1832, is also used for d~vine service. There is a at 5 p.m. Postal orders are issued here, but not paid. charity of 30s. yearly for distribution in bibles; Dawson The nearest money. ordeT office is at Macclesfield. Bos- ~ and Thornley's, of £2 7s. 4d. for distribution in money ley Station is the nearest telegraph office and bible~s in Bosley and the neighbourhood and Roger Letter Box at Dane Mill clea!'ed .at 4.30 p.m · Holland's, of £5 yearly, due on St. Thomas' day, being a Railway Station, Herbert Capper Marlow, ~Station master charge on Hunter's Pool Farm at ;Mottram St. Andrew. National School (mixed), built with residence for the A fine sheet of water, covering 120 acres, is used as a master in 185·8 & is now (1896) bein~ .e-nlarged for go reservoir for the Macclesfield canal.