The Distribution and Status of the Polecat (Mustela Putorius) in Britain 2014-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Topic Paper 5: Natural Environment/Biodiversity

Wiltshire Local Development Framework Working towards a Core Strategy for Wiltshire Draft topic paper 5: Natural environment/biodiversity Wiltshire Core Strategy Consultation June 2011 Wiltshire Council Information about Wiltshire Council services can be made available on request in other languages including BSL and formats such as large print and audio. Please contact the council on 0300 456 0100, by textphone on 01225 712500 or by email on [email protected]. Wiltshire Core Strategy Natural Environment Topic Paper 1 This paper is one of 18 topic papers, listed below, which form part of the evidence base in support of the emerging Wiltshire Core Strategy. These topic papers have been produced in order to present a coordinated view of some of the main evidence that has been considered in drafting the emerging Core Strategy. It is hoped that this will make it easier to understand how we had reached our conclusions. The papers are all available from the council website: Topic Paper TP1: Climate Change TP2: Housing TP3: Settlement Strategy TP4: Rural Issues (signposting paper) TP5: Natural Environment/Biodiversity TP6: Water Management/Flooding TP7: Retail TP8: Economy TP9: Planning Obligations TP10: Built and Historic Environment TP11:Transport TP12: Infrastructure TP13: Green Infrastructure TP14:Site Selection Process TP15:Military Issues TP16:Building Resilient Communities TP17: Housing Requirement Technical Paper TP18: Gypsy and Travellers 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................5 -

Green Infrastructure

Wiltshire Local Development Framework Working towards a Core Strategy for Wiltshire Topic paper 11: Green infrastructure Wiltshire Core Strategy Consultation January 2012 Wiltshire Council Information about Wiltshire Council services can be made available on request in other languages including BSL and formats such as large print and audio. Please contact the council on 0300 456 0100, by textphone on 01225 712500 or by email on [email protected]. This paper is one of 16 topic papers, listed below, which form part of the evidence base in support of the emerging Wiltshire Core Strategy. These topic papers have been produced in order to present a coordinated view of some of the main evidence that has been considered in drafting the emerging Core Strategy. It is hoped that this will make it easier to understand how we have reached our conclusions. The papers are all available from the council website: Topic Paper 1: Climate Change Topic Paper 2: Housing Topic Paper 3: Settlement Strategy Topic Paper 4: Rural Signposting Tool Topic Paper 5: Natural Environment Topic Paper 6: Retail Topic Paper 7: Economy Topic Paper 8: Infrastructure and Planning Obligations Topic Paper 9: Built and Historic Environment Topic Paper 10: Transport Topic Paper 11: Green Infrastructure Topic Paper 12: Site Selection Process Topic Paper 13: Military Issues Topic Paper 14: Building Resilient Communities Topic Paper 15: Housing Requirement Technical Paper Topic Paper 16: Gypsy and Travellers Contents 1. Executive summary 1 2. Introduction 2 2.1 What is green infrastructure (GI)? 2 2.2 The benefits of GI 4 2.3 A GI Strategy for Wiltshire 5 2.4 Collaborative working 6 3. -

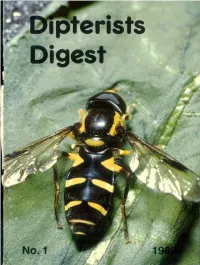

Ipterists Digest

ipterists Digest Dipterists’ Digest is a popular journal aimed primarily at field dipterists in the UK, Ireland and adjacent countries, with interests in recording, ecology, natural history, conservation and identification of British and NW European flies. Articles may be of any length up to 3000 words. Items exceeding this length may be serialised or printed in full, depending on the competition for space. They should be in clear concise English, preferably typed double spaced on one side of A4 paper. Only scientific names should be underlined- Tables should be on separate sheets. Figures drawn in clear black ink. about twice their printed size and lettered clearly. Enquiries about photographs and colour plates — please contact the Production Editor in advance as a charge may be made. References should follow the layout in this issue. Initially the scope of Dipterists' Digest will be:- — Observations of interesting behaviour, ecology, and natural history. — New and improved techniques (e.g. collecting, rearing etc.), — The conservation of flies and their habitats. — Provisional and interim reports from the Diptera Recording Schemes, including provisional and preliminary maps. — Records of new or scarce species for regions, counties, districts etc. — Local faunal accounts, field meeting results, and ‘holiday lists' with good ecological information/interpretation. — Notes on identification, additions, deletions and amendments to standard key works and checklists. — News of new publications/references/iiterature scan. Texts concerned with the Diptera of parts of continental Europe adjacent to the British Isles will also be considered for publication, if submitted in English. Dipterists Digest No.1 1988 E d ite d b y : Derek Whiteley Published by: Derek Whiteley - Sheffield - England for the Diptera Recording Scheme assisted by the Irish Wildlife Service ISSN 0953-7260 Printed by Higham Press Ltd., New Street, Shirland, Derby DE5 6BP s (0773) 832390. -

The Natural History of Wiltshire

The Natural History of Wiltshire John Aubrey The Natural History of Wiltshire Table of Contents The Natural History of Wiltshire.............................................................................................................................1 John Aubrey...................................................................................................................................................2 EDITOR'S PREFACE....................................................................................................................................5 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................................12 INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. CHOROGRAPHIA.................................................................................15 CHOROGRAPHIA: LOCAL INFLUENCES. 11.......................................................................................17 EDITOR'S PREFACE..................................................................................................................................21 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................................28 INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. CHOROGRAPHIA.................................................................................31 CHOROGRAPHIA: LOCAL INFLUENCES. 11.......................................................................................33 CHAPTER I. AIR........................................................................................................................................36 -

The 2008 IUCN Red Listings of the World's Small Carnivores

The 2008 IUCN red listings of the world’s small carnivores Jan SCHIPPER¹*, Michael HOFFMANN¹, J. W. DUCKWORTH² and James CONROY³ Abstract The global conservation status of all the world’s mammals was assessed for the 2008 IUCN Red List. Of the 165 species of small carni- vores recognised during the process, two are Extinct (EX), one is Critically Endangered (CR), ten are Endangered (EN), 22 Vulnerable (VU), ten Near Threatened (NT), 15 Data Deficient (DD) and 105 Least Concern. Thus, 22% of the species for which a category was assigned other than DD were assessed as threatened (i.e. CR, EN or VU), as against 25% for mammals as a whole. Among otters, seven (58%) of the 12 species for which a category was assigned were identified as threatened. This reflects their attachment to rivers and other waterbodies, and heavy trade-driven hunting. The IUCN Red List species accounts are living documents to be updated annually, and further information to refine listings is welcome. Keywords: conservation status, Critically Endangered, Data Deficient, Endangered, Extinct, global threat listing, Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable Introduction dae (skunks and stink-badgers; 12), Mustelidae (weasels, martens, otters, badgers and allies; 59), Nandiniidae (African Palm-civet The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the most authorita- Nandinia binotata; one), Prionodontidae ([Asian] linsangs; two), tive resource currently available on the conservation status of the Procyonidae (raccoons, coatis and allies; 14), and Viverridae (civ- world’s biodiversity. In recent years, the overall number of spe- ets, including oyans [= ‘African linsangs’]; 33). The data reported cies included on the IUCN Red List has grown rapidly, largely as on herein are freely and publicly available via the 2008 IUCN Red a result of ongoing global assessment initiatives that have helped List website (www.iucnredlist.org/mammals). -

Monitoring of Forest Mammals Listed in the Annexes IV and V of the Habitat Directive (Except Bats)

Monitoring biodiversity in Luxembourg: what is left to be done? 22 November 2017 Monitoring of forest mammals listed in the Annexes IV and V of the Habitat Directive (except bats) Distribution and evolution since 2010: Marc Moes GEODATA • Hazel dormouse, • Wildcat, Xavier Mestdagh • Pine marten, Lionel L’Hoste • Polecat. LIST Hazel Dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius 2 Hazel Dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius Methodology • Identification of “potentially” suitable habitats • Random and stratified sampling design 90 squares (1x1 Km) selected Looking for “summer” nest in 4 “favourable” sites/square during Oct/Nov Mainly brambles, shrub covered area and forest edge • Triennal sampling procedure 3 Hazel Dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius Results • Since 2010: 102 squares were surveyed • 2017 sampling is still in progress • From 2013 to 2015: repeated survey for some squares 1st passage: 1124 sites investigated so far! 4 Hazel Dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius Results: Sites level (1st passage) 1st passage 2010-2012 2013-2015 2016-2018 Number of sites 596 336 192 surveyed ( + + ) = 1124 sites Number of favourable sites 294 269 149 surveyed Number of favourable sites 108 169 83 with proof of presence Average= 51% 5 Hazel Dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius Results: Squares level - analysis based on the 1st passage 1st passage 2010-2012 2013-2015 2016-2018 2010/ 2013/ 2012 2015 Number of squares ✔ ✔ surveyed with at least one 96 78 28 favourable site ✔ ✘ Number of squares ✘ ✔ surveyed with at least one ✘ ✘ favourable site 70 66 26 AND with proof -

Molecular Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the Genus Mustela

Mammal Study 33: 25–33 (2008) © the Mammalogical Society of Japan Molecular phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Mustela (Mustelidae, Carnivora), inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences: New perspectives on phylogenetic status of the back-striped weasel and American mink Naoko Kurose1, Alexei V. Abramov2 and Ryuichi Masuda3,* 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Kanagawa University, Kanagawa 259-1293, Japan 2 Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Saint-Petersburg 199034, Russia 3 Creative Research Initiative “Sousei”, Hokkaido University, Sapporo 060-0810, Japan Abstract. To further understand the phylogenetic relationships among the mustelid genus Mustela, we newly determined nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene from 11 Eurasian species of Mustela, including the domestic ferret and the American mink. Phylogenetic relationships inferred from the 12S rRNA sequences were similar to those based on previously reported mitochondrial cytochrome b data. Combined analyses of the two genes demonstrated that species of Mustela were divided into two primary clades, named “the small weasel group” and “the large weasel group”, and others. The Japanese weasel (Mustela itatsi) formerly classified as a subspecies of the Siberian weasel (M. sibirica), was genetically well-differentiated from M. sibirica, and the two species clustered with each other. The European mink (M. lutreola) was closely related to “the ferret group” (M. furo, M. putorius, and M. eversmanii). Both the American mink of North America and the back-striped weasel (M. strigidorsa) of Southeast Asia were more closely related to each other than to other species of Mustela, indicating that M. strigidorsa originated from an independent lineage that differs from other Eurasian weasels. -

Helminths of Mustelids (Mustelidae) in Lithuania

BIOLOGIJA. 2014. Vol. 60. No. 3. P. 117–125 © Lietuvos mokslų akademija, 2014 Helminths of mustelids (Mustelidae) in Lithuania Dovilė Nugaraitė, This study provides new faunistic data for helminths of muste lids in Lithuania. Twentyfive mustelids were examined for hel Vytautas Mažeika*, minths: 2 pine martens (Martes martes), 4 stone martens (Mar tes foina), 9 American minks (Neovison vison) and 10 European Algimantas Paulauskas polecats (Mustela putorius). Nine taxa of the parasitic worms were found: trematodes Isthmiophora melis (Schrank, 1788) and Stri Faculty of Natural Sciences, gea strigis (Schrank, 1788) mesocercaria, cestodes Mesocestoides Vytautas Magnus University, lineatus Goeze, 1782 and Cestoda g. sp. and nematodes Eucoleus Vileikos str. 8, aerophilus (Creplin, 1839), Aonchotheca putorii (Rudolphi, 1819), LT-44404 Kaunas, Lithuania Crenosoma schachmatovae Kontrimavičius, 1969, Molineus pa tens (Rudolphi, 1845) and Nematoda g. sp. The biggest infection parameters were detected for flukes Isthmiophora melis and Stri gea strigis mesocercaria in American mink and European pole cat. In most cases the distribution of helminths in populations of mustelids was aggregated (s2/A > 1). Key words: mustelids, helminths, Lithuania INTRODUCTION melis (recorded under name Euparyphium me lis) were found. Both pine marten and Eurasian In Lithuania pine marten (Martes martes), stone badger were infected by nematodes Aonchotheca marten (Martes foina), stoat (Mustela erminea), putorii (recorded under name Capillaria putorii) least weasel (Mustela nivalis), European pole and Filaroides martis. Only Eurasian badger cat (Mustela putorius), American mink (Neovi was parasitized by cestode Mesocestoides linea son vison), Eurasian badger (Meles meles) and tus and nematodes Trichinella spiralis and Unci European otter (Lutra lutra) are found. -

“Brilliant Britain” on Stamps

Stamp Fun “Brilliant Britain” on Stamps £3.00 Stamp Active Network In association with The Great Britain Philatelic Society Welcome to Stamp Active Stamp Active is a voluntary organisation which promotes stamp collecting for young people in the UK. This pack provides some activities for you to complete. If you finish five of the activities in the pack, please take it to one of the organisers at a Stamp Active event and you will receive a prize. There is plenty more for you to do in the pack or you can have a go at some of the other stamp competitions promoted by Stamp Active. The pack is yours to keep and it will give you a useful guide to some of the varied aspects of stamp collecting. Have Fun! Kids Corner, sponsored by The Philatelic Traders Society, Stamp Active Network is supported by major sponsors which takes place at Spring and Autumn Stampex, held including The Philatelic Fund, Stanley Gibbons, at the Business Design Centre, Islington, London. The Association of British Philatelic Societies, The Philatelic Traders Society, and The Great Britain Philatelic Society The Stamp Active Competition, sponsored by the as well as many other dealers, individuals and clubs and GBPS and The British Youth Stamp Championships, societies. Special thanks to Ian Varey for his development sponsored by Stanley Gibbons, for those interested in of the ideas for this activity pack. displaying their collections. We are always in need of financial donations or the gift Stamp Active Web Site to find out more about collecting of stamps, covers and other material. -

Analysis of Snake Creek Burial Cave Mustela Fossils Using Linear

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2014 Analysis of Snake Creek Burial Cave Mustela fossils using Linear & Landmark-based Morphometrics: Implications for Weasel Classification & Black- footed Ferret Conservation Nathaniel S. Fox III East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Fox, Nathaniel S. III, "Analysis of Snake Creek Burial Cave Mustela fossils using Linear & Landmark-based Morphometrics: Implications for Weasel Classification & Black-footed Ferret Conservation" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2339. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2339 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analysis of Snake Creek Burial Cave Mustela fossils using Linear & Landmark-based Morphometrics: Implications for Weasel Classification & Black-footed Ferret Conservation _______________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Geosciences East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Geosciences _______________________________________ by Nathaniel S. Fox May 2014 _______________________________________ Dr. Steven C. Wallace, Chair Dr. Jim I. Mead Dr. Blaine W. Schubert Keywords: Mustela, weasels, morphometrics, classification, conservation, Pleistocene, Holocene ABSTRACT Analysis of Snake Creek Burial Cave Mustela fossils using Linear & Landmark-based Morphometrics: Implications for Weasel Classification & Black-footed Ferret Conservation by Nathaniel S. -

Westminster Parliamentary Constituency Parking Or Street Parking Off-Street Parking Households Parking Or Parking Or Parking Potential Potential Potential

Households Households Proportion of with off-street without off- households with Total Westminster Parliamentary Constituency parking or street parking off-street parking households parking or parking or parking potential potential potential Makerfield 43,151 37,502 5,649 87% Sefton Central 36,870 31,835 5,035 86% Rother Valley 43,277 37,156 6,121 86% St Helens North 45,216 38,745 6,471 86% Alyn and Deeside 36,961 31,455 5,506 85% Don Valley 44,413 37,454 6,959 84% Stoke-on-Trent South 40,222 33,856 6,366 84% Hemsworth 44,346 37,093 7,253 84% Leigh 47,922 40,023 7,899 84% Cheadle 40,075 33,373 6,702 83% Knowsley 49,055 40,840 8,215 83% Ellesmere Port and Neston 41,209 34,289 6,920 83% South Ribble 43,214 35,946 7,268 83% Wyre and Preston North 41,121 34,181 6,940 83% Doncaster North 44,508 36,929 7,579 83% Delyn 31,517 26,116 5,401 83% Vale of Clwyd 32,766 27,083 5,683 83% Islwyn 33,336 27,431 5,905 82% Caerphilly 38,136 31,371 6,765 82% Bridgend 37,089 30,418 6,671 82% Llanelli 37,886 31,008 6,878 82% Wirral South 32,535 26,623 5,912 82% Aberavon 30,961 25,333 5,628 82% Wirral West 31,312 25,549 5,763 82% East Dunbartonshire 35,778 29,131 6,647 81% Elmet and Rothwell 45,553 37,037 8,516 81% Barnsley East 42,702 34,711 7,991 81% Blackpool North and Cleveleys 38,710 31,423 7,287 81% Redcar 40,869 33,166 7,703 81% Gower 36,618 29,704 6,914 81% St Helens South and Whiston 48,009 38,931 9,078 81% Congleton 46,229 37,449 8,780 81% Mid Derbyshire 38,073 30,812 7,261 81% Scunthorpe 39,213 31,683 7,530 81% Penistone and Stocksbridge 40,347 32,557 -

Appendix-D Methodology of Standardised Acceptance Rates

Appendix D: Methodology of standardised acceptance rates calculation and administrative area geography and Registry population groups in England & Wales Chapter 4, on the incidence of new patients, includes Greater London is subdivided into the London an analysis of standardised acceptance rates in Eng- Boroughs and the City of London. land & Wales for areas covered by the Registry. The methodology is described below. This methodology is also used in Chapter 5 for analysis of prevalent Unitary Authorities patients. Table D.1: Unitary Authorities Code UA name Patients 00EB Hartlepool 00EC Middlesbrough All new cases accepted onto RRT in each year 00EE Redcar and Cleveland recorded by the Registry were included. Each 00EF Stockton-on-Tees patient’s postcode was matched to a 2001 Census 00EH Darlington output area. In 2003 there were only 14 patients 00ET Halton with postcodes that had no match; there was no 00EU Warrington obvious clustering by renal unit. 00EX Blackburn with Darwen 00EY Blackpool Geography: Unitary 00FA Kingston upon Hull, City of Authorities, Counties and other 00FB East Riding of Yorkshire 00FC North East Lincolnshire areas 00FD North Lincolnshire 00FF York In contrast to 2002 contiguous ‘county’ areas were 00FK Derby not derived by merging Unitary Authorities (UAs) 00FN Leicester with a bordering county. For example, Southampton 00FP Rutland UA and Portsmouth UA were kept separate from 00FY Nottingham Hampshire county. The final areas used were Metro- 00GA Herefordshire, County of politan counties, Greater London districts, Welsh 00GF Telford and Wrekin areas, Shire counties and Unitary Authorities – these 00GL Stoke-on-Trent different types of area were called ‘Local Authority 00KF Southend-on-Sea (LA) areas’.