Uq0336c4b OA.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9781920898359 Appendices R

319 Appendix 1 University leadership Fellows of the Senate Students, Deputy Chair of Academic Staff or Alumni of the Board from 1980 Faculty from 1980 1978–1980 John Young 1978–1981 John Young 1986 Susan Dorsch 1979–1993 Katherine Georgouras 1986–1987 Ann Sefton 1983–1986 Andrew Refshauge 1991–1993 Alan Pettigrew 1986–1987 Diana Temple 1992–1996 James Lawrence 1987 Alan Cass 1996 Ann Sefton 1989 Anna Donald 1989 Tony Sara Senate Deputy Chancellor 1989 Eric Wegman from 1980 1990–1991 Natalie Smith 2004– Ann Sefton 1993–1995 Douglas Baird 1995–2002 Stephen Leeder 1996–2001 Michael Copeman 1997– Robin Fitzsimons 1997–2001 Peter Burrows 2001– Ann Sefton 2005– Michael Copeman 320 Appendix 2 Deans of the Faculty of Medicine from 1980 1974 –1989 Richard S Gye 1989 –1996 John Atherton Young 1997–2002 Stephen Leeder 2003 – Andrew Coats Appendix 3 Current Emeritus Professors Barry Baker John Little Tony Basten William McCarthy Geoffrey Berry James McLeod Charles Blackburn Russell Meares Charles Bridges-Webb Gerald Milton Neil Buchanan Kim Oates Peter Castaldi Murray Pheils John Chalmers Wai-On Phoon Patrick De Burgh Thomas Reeve Susan Dorsch Douglas Saunders Hans Freeman Ann Sefton Kerry Goulston Ainslie Sheil Richard Gye Frederick Stephens Akos Gyory Michael Taylor Noel Hush Thomas Taylor Gordon Johnson Stewart Truswell Charles Kerr John Turtle James Lawrence Robert Wake 321 Appendix 4 Professors appointed or promoted 1980–2005 1980 W Cramond 1989 Nicholas Hunt 1994 Leigh Delbridge 1980 Graeme Johnston 1989 John Sutton 1994 Ian Frazer 1980 Philip -

Laureate Professor Nicholas Talley

CHAIR: Laureate Professor Nicholas Talley Professor Talley is currently Pro Vice-Chancellor, Global Research at the University of Newcastle, Australia. He is an expert clinician, educator and researcher. He has published over 890 original and review articles in the peer-reviewed literature, and is considered one of the world’s most influential clinician-researchers, and is also a leading medical educator and the author of the highly regarded textbooks Clinical Examination and Examination Medicine. In June 2014, Professor Talley was inaugurated as one of the first 15 Fellows of the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences (FAHMS) and was elected to the Executive of the Academy. He has held roles as Co-Editor-in-Chief of Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics for 6 years, and completed two 3- year terms (as Co-Editor-in-Chief of the American Journal of Gastroenterology. He is a Section Editor for the on-line textbook Up To Date. Professor Talley was formerly Professor of Medicine and Professor of Epidemiology and Chair of the Department of Internal Medicine at Mayo Clinic in Florida, USA, and previously Foundation Professor of Medicine at the University of Sydney. Professor Talley is a Staff Specialist Gastroenterologist at John Hunter Hospital and current researcher with the Mayo Clinic, University of North Carolina and the Karolinska Institute. He is a Fellow and Past President of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians; Fellow the Royal College of Physicians (both London and Edinburgh), the American College of Physicians, the American College of Gastroenterology and the AGA. He is the recipient of a number of prestigious awards. -

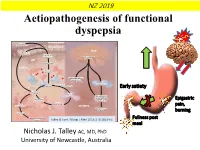

Aetiopathogenesis of Functional Dyspepsia

NZ 2019 Aetiopathogenesis of functional dyspepsia Genetic DUODENAL LUMEN predisposition GUT EPITHELIUM BRAIN ↑ Epithelial permeability Pathogens or allergens Anxiety or stress response APC Eotaxin release LAMINA PROPRIA Eosinophil activation Disordered motility and visceral hypersensitivity Immune cells Th2-cell Interleukin-4 response Interleukin-13 Interleukin-5 Early satiety Eosinophil degranulation B-cell response ↑ Inflammatory cytokines TNFα, Eosinophil interleukin-10, and Epigastric recruitment interleukin-1β Release of Nerve proallergic IgE pain, infringement DUODENUM Delayed gastric emptying burning Nerve firing Muscle contractions Fullness post and pain Talley & Ford.MUSCL NE FIBER EnglS J Med 2015:373:1853-63 meal Nicholas J. Talley AC, MD, PhD University of Newcastle, Australia Disclosures Grant / Research Support Committees Commonwealth Diagnostics (International) (IBS) Australian Medical Council (AMC) Council Member (ceased 2017) MBS Review Taskforce NHMRC Principal Committee, Research Committee HVN National Science Challenge NZ (no financial Asia Pacific Association of Medical Journal Editors (APAME) support) Patents Consultancies Biomarkers of irritable bowel syndrome (#12735358.9 - Takeda (gastroparesis) 1405/2710383 and (#12735358.9 -1405/2710384) Adelphi values (functional dyspepsia working group to develop a symptom based PRO instrument) Licensing Questionnaires (Mayo Clinic) Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire, Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire Allergens PLC GI therapies (non-invasive device company, consultant and Nestec European Patent Application No. 12735358.9 options) Singapore ‘Provisional’ Patent NTU Ref: TD/129/17 IM Health Sciences, USA “Microbiota Modulation of BDNF Tissue Repair Napo Pharmaceutical Pathway” Outpost Medicine Editorial Samsung Bioepis Synergy Medical Journal of Australia (Editor-in-Chief) Theravance Up to Date (Section Editor) Avant Foundation (judging of research grants) Precision and Future Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, South Korea Community and patient advocacy groups Boards GESA Board Member. -

MJA Editor-In-Chief Is Australia's Most Cited Academic

MJA Editor-In-Chief is Australia’s most cited academic Australia’s leading medical journal – with a 5-year impact factor of 4.1 – is headed by the country’s top researcher from the University of Newcastle, according to a new report from Google Scholar . The Medical Journal of Australia’s Editor-in-Chief Laureate Professor Nicholas Talley is the highest ranking in a list of the top 1,000 scientists from Australian institutions according to their Google Scholar Citations profiles . The researchers are ranked by h-index, which combines measures of both their productivity and citation impact. Professor Talley is a global authority in neurogastroenterology and incurable functional gut disorders that affect more than one in five Australians. His recent work linking the gut as a major driver of anxiety and other changes in the brain has contributed to a paradigm shift in the way we understand how the gut interacts with the brain. This new approach may eventually unlock new therapies not just for gut conditions, but also for intractable neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s. Professor Talley’s groundbreaking work with Professor Marjorie Walker at the University of Newcastle has led to the discovery of two new gut diseases in conditions that were previously thought to have no known cause: duodenal eosinophilia in dyspepsia, and large bowel eosinophilia linked to colonic bacteria in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). His other major work has identified a link between autoimmune and unexplained gut disease , which could lead to new treatment approaches. His team is investigating the role of environmental and dietary factors including wheat in causing these gut problems. -

Clinical Examination a Systematic Guide to Physical Diagnosis

7 EDITION clinical examination A systematic guide to physical diagnosis Nicholas J Talley and Simon O’Connor sample proofs © Elsevier Australia clinical examination A systematic guide to physical diagnosis Seventh edition Nicholas J Talley MB BS (Hons), MMedSc (Clin Epi) (Newc), MD (NSW), PhD (Syd), FRACP, FAFPHM, FRCP (Lond), FRCP (Edin), FACP, FACG, AGAF Pro Vice-Chancellor and Dean (Health and Medicine), and Professor, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia; Senior Staff Specialist, John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, NSW, Australia; Adjunct Professor of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States; Adjunct Professor of Medicine, University of North Carolina, United States; Foreign Guest Professor, Karolinska Institute, Sweden; President-Elect, Royal Australasian College of Physicians Simon O’Connor FRACP, DDU, FCSANZ Cardiologist, The Canberra Hospital; Clinical Senior Lecturer, Australian National University Medical School, Canberra, ACT, Australia Sydney Edinburgh London New York Philadelphia St Louis Toronto sample proofs © Elsevier Australia Churchill Livingstone is an imprint of Elsevier Elsevier Australia. ACN 001 002 357 (a division of Reed International Books Australia Pty Ltd) Tower 1, 475 Victoria Avenue, Chatswood, NSW 2067 This edition © 2014 Elsevier Australia 6th edn 2010; 5th edn 2006; 4th edn 2001; 3rd edn 1996; 2nd edn 1992; 1st edn 1988 eISBN: 9780729581479 This publication is copyright. Except as expressly provided in the Copyright Act 1968 and the Copyright Amendment (Digital Agenda) Act 2000, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted by any means (including electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher. Every attempt has been made to trace and acknowledge copyright, but in some cases this may not have been possible. -

MJA Editor-In-Chief Wins Top Honour Top Wins Editor-In-Chief MJA L C2 MJA 208 (3) • 19 February 2018 Dr Davidsinclair: and Care

Careers MJA editor-in-chief wins top honour Professor Nick Talley, editor-in-chief of the MJA, is one of six medical practitioners to win the country’s highest honour, Companion in the General Division of the Order of Australia … AUREATE Professor Nicholas Talley, University of the same time minimise waste and reduce costs. We can easily Newcastle, NSW, and editor-in-chief of the Medical Journal become complacent about health but that would be wrong, Lof Australia, has been named a Companion (AC) in the because we can be better.” General Division of the Order of Australia. Professor Talley is a household name to many doctors in Professor Talley’s citation reads: Australia today. His medical textbooks, along with co-author “For eminent service to medical Dr Simon O’Connor, are used in nearly every medical school research, and to education in the across Australia and many internationally. field of gastroenterology and He has been instrumental in guiding peer-reviewed epidemiology, as an academic, medical publications. He was editor of the American Journal author and administrator at of Gastroenterology from 2004 to 2009; editor of Alimentary the national and international Pharmacology and Therapeutics from 2009 to 2015; and, has been level, and to health and scientific editor-in-chief of the MJA since 2015. associations.” Professor Talley said he could not have accepted so many Currently Pro Vice-Chancellor “extra-curricular” roles without the help of the University of (Global Research) at the University Newcastle (UoN). of Newcastle, and a senior staff specialist in gastroenterology at “I have to thank UoN for their fantastic support,” he said. -

Functional Dyspepsia

VOLUME 40 : NUMBER 6 : DECEMBER 2017 ARTICLE Functional dyspepsia Nicholas J Talley SUMMARY Laureate professor1 Pro‑vice‑chancellor1 Functional dyspepsia is characterised by troublesome early satiety, fullness, or epigastric pain Thomas Goodsall or burning. It can easily be overlooked as the symptoms overlap with gastro-oesophageal reflux Conjoint research fellow1 disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Registrar2 Diagnosis is clinical, however it requires exclusion of structural gastrointestinal disease. Michael Potter The presence of red flags, such as weight loss or anaemia, should prompt investigation Conjoint research fellow1 including gastroscopy. Registrar2 The pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia is not completely understood. It is thought to be 1 Global Research associated with upper gastrointestinal inflammation and motility disturbances, which may be University of Newcastle triggered by an infectious or allergenic agent, or a change in the intestinal microbiome. Slow 2 Department of gastric emptying occurs in 20% of cases. Gastroenterology John Hunter Hospital While functional dyspepsia is distressing and affects quality of life, it has no long-term impacts Newcastle on mortality. New South Wales There are many treatment options available, with varying levels of evidence of efficacy. These Keywords include reassurance, dietary modification, acid suppression, prokinetic drugs including fundic dyspepsia, endoscopy, relaxors, tricyclic antidepressants, rifaximin and psychological therapy. gastro‑oesophageal reflux, H2 receptor antagonists, proton pump inhibitors Introduction gastroscopy, and are labelled as having functional or 4,6 Functional dyspepsia is a common problem in non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aust Prescr 2017;40:209–13 Australia and often impacts on quality of life and work Correctly diagnosing functional dyspepsia is productivity.1,2 It affects 10% of the population and is important to guide appropriate therapy and reduce https://doi.org/10.18773/ austprescr.2017.066 more prevalent in women.3-5 unnecessary procedures or treatments. -

Physicians' Preferences for Hospice If They Were Terminally Ill and The

Letters in 5.6% and 0.36%, respectively, only marginally less than the 6. Vakil N, Moayyedi P, Fennerty MB, Talley NJ. Limited value of alarm features prevalence in those with symptomatic GERD.7 in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal malignancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(2):390-401. The difficulty in identifying the right patients with GERD 7. Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, et al. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus in to endoscope is demonstrated in the study by Kramer et al,8 colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterology. published in this issue. In an impressive audit of nearly 500 000 2003;125(6):1670-1677. cases of GERD identified in Veteran Health Administration rec- 8. Kramer JR, Shakhatreh MH, Naik AD, Duan Z, El-Serag HB. Use and yield of ords, the authors found that those patients more likely to re- endoscopy in patients with uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux disorder ceive an EGD in the first year after diagnosis were actually less [published online January 27, 2014]. JAMA Intern Med. doi:10.1001/ jamainternmed.2013.12756. likely to have either BE or esophageal cancer.8 Men older than 9. Dulai GS, Guha S, Kahn KL, Gornbein J, Weinstein WM. Preoperative 65 years, for example, were nearly 7-fold more likely to have prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in esophageal adenocarcinoma: a systematic BE or esophageal cancer compared with a cohort of women review. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(1):26-33. younger than 50 years as the reference group, but these men 10. Chang JY, Locke GR III, McNally MA, et al. -

Preface ...4 Scientific Program

Preface . 4 Scientific Program . 6 Posters . 12 List of Speakers . 18 Information . 24 11 credit hours (CME) have been awarded to the Symposium 207 by the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) - European Board of Gastroenterology . 3 13635_Falk_Brisbane_Symp_207_Prog_Inhalt.indd 3 30.03.17 10:49 Preface In recent years medicine has witnessed an astonishing paradigm shift . For decades it was believed that for most diseases the individual risk was defined by the genetic make-up, potentially modified by the environment and lifestyle-factors . It has now emerged that the gut microbiome plays an equally important role for many gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal disorders . This opens astonishing new avenues to understand and target disease mechanisms in particular in relation to immune mediated diseases but might be equally important for the prevention of disease . Thus the organisers Gerald Holtmann and Mark Morrison from Brisbane, Nicholas Talley from Newcastle, William Chey from Ann Arbor, and Peter Gibson from Melbourne in close collaboration with other experts in the field have developed a scientific program that brings together basic scientists and clinicians from many disciplines to define our current knowledge and define future directions that are relevant for the translation of this knowledge into clinical practice . On behalf of the scientific committee Prof . Gerald Holtmann, Brisbane 4 13635_Falk_Brisbane_Symp_207_Prog_Inhalt.indd 4 30.03.17 10:49 Symposium 207 Gut Microbiome and Mucosal or Systemic Dysfunction: Mechanisms, Clinical Manifestations and Interventions May 19 – 20, 2017 Brisbane Convention & Exhibition Centre Scientifi c Organization: Prof . Gerald Holtmann Brisbane, Australia Princess Alexandra Hospital University of Queensland 199 Ipswich Road Brisbane, QLD 4102, Australia Telephone: +617 31 76 77 92 Telefax: +617 31 76 51 11 Registration: E-Mail: g .holtmann@uq .edu .au Thursday, May 18, 2017 16 .00 – 21 .00 h Scientifi c Co-Organization: at the congress offi ce W .D .