The Zimmerman Family Reunion Tina A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home to Thanksgiving!

HOME TO THANKSGIVING! by Peggy M. Baker, Director & Librarian, Pilgrim Society An exhibit sponsored by the John Carver Inn & Hearth 'n Kettle Restaurants November - December 1999 Home to Thanksgiving! The words conjure up pictures: bright and frosty New England mornings, a white- steepled church set in rolling hills, the joyous arrival of a brother or sister home from school, eager children in the back seat of the family sedan asking "Are we there yet?", grandparents opening the door of the old homestead, beaming faces of all ages around a crowded dining room table. This is Thanksgiving: images of New England, memories of family. In addition to prints and posters, essays and poetry celebrating the New England Thanksgiving and family reunions through the years, we pay tribute to New England's Lydia Maria Child: writer, editor, gifted scholar, courageous early leader of the abolitionist movement, and the author of the unofficial Thanksgiving family reunion anthem "Over the river and through the wood to grandfather's house we go." Home ...to New England! "Did you ever make one of a thanksgiving party, in that section of the globe called the land of steady habits? New England is the place of all others for these festivals. There is no genuine, legitimate thanksgiving out of New England, unless it is imported by New England's sons and daughters. The festival originated there, and there you must go if you want to see it kept in the old-fashioned style." Thanksgiving Festival in New England, The Youth's Cabinet, 1846. Home ...to the Family! "Thanksgiving .. -

The Gathering Barn Information 3.27.19

At Old McDonald’s Farm § We can host your: § Fundraiser dinner, § Birthday Party, § Celebration of Life, § Shower, § FRG or Hail & Farewell, § Retirement Party, § Company or Family Christmas Party, § Wedding, § Sweet 16, § Anniversary Party, § Annual Meeting, § Prom, § Training, § Family Reunion, § And any other celebration! § Graduation Party, § Class Reunion, BIRTHDAY PARTY § Included in the $230 Birthday Party Package: § 30 people § Time slots of 10am- 1:00pm or 2:30-5:30 pm (May-October) § Hands on visit with over 200 animals § Wizard of Oz Hayride (Add Tour of North Harbor Dairy $30) § Bounce houses § Bucket of goat food for children § Pony rides for children § HALF of our new modern heated, air-conditioned Event Barn (w/ private bathrooms) § Festive tablecloths and balloons! § ($400 for entire space in Event Barn and 50 people) § Contact us for winter rates and availibility § Included in the $400 Special Occasion Package: § Seating for up to 125 people § Reservation for entire space of the Event Barn (with private bathrooms) for the whole day § Ivory table linens or festive party linens § Guests are welcome to visit Old McDonald’s Farm animals during regular business hours. (They must check-in at the admissions desk in the Visitors Center). § All alcohol must be catered by a vendor with a valid liquor license or lessee must obtain liquor license § Let us take care of the catering (May-October) or hire your own company. § $275: Special weekday evening rate, after 5 pm, Monday- Friday May through October OR offseason rate November- April any day of the week for the whole day § We invite you to come and enjoy your special day in our Gathering Barn. -

Current River Community Centre

CurrentCurrent RiverRiver CommunityCommunity CentreCentre FamilyFamily membershipmembership isis $5.00$5.00 perper family.family. CRRA Board Meetings Programs The meetings are held the 3rd Monday of each • Quilting & CRAFTING GROUP: Every Mon af- month at 1pm (except for the summer). ternoon from 1 to 4pm. No formal instruction. Come Volunteers out and sew your quilts & finish crafting projects with Volunteers are essential to your Community Centre. others. This is a good time for you all to get together COMMUNITY CENTRES COMMUNITY Please come and donate an hour of your time and and finish your own projects and help others with www.thunderbay.ca/communitycentres have fun doing it. There are events for all ages. theirs. From Sept to mid June. Fee $4.00, drop in. Call 683-8451 for more info. Hall Rentals • Parents & Tots: Moms and Dads, tired of only hav- We feature 2 rooms for rentals - the Cedar Star Room ing a baby to talk to in the morning. Bring your chil- and a small meeting room. We provide full banquet dren out to play with other kids on Monday, Tuesday, catering services for weddings, banquets, as well as Wednesday, and Thursday mornings from 9:30 to catering for luncheons, teas, showers, funerals, etc. All 11:15am. Fee is $4.00 per child and 50 cents each ad- your catering and non-catering events. Call Pat Baker, ditional child. Daily activities, free play. Juice is pro- Hall Manager, to book your event at 683-8451. vided. Except for the 1st Tuesday of every month. Boys and Girls Soccer, CRRA Thunder Bay Call centre for more information at 683-8451. -

November 1, 2020 CORPUS CHRISTI COMMUNITY

orpus Christi Catholic Community 6001 Bob Billings Parkway C part of the Catholic Church of Northeast Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 66049V5200 785V843V6286 www.cccparish.org November 1, 2020 CORPUS CHRISTI COMMUNITY How Halloween and ALL Saints Go Together Every year, people and well meaning Christians seem to question how Halloween should be celebrated in respect to our faith. This Halloween will be quite different from the normal thanks to the pandemic. Halloween is a holiday Catholics should embrace in its original form so a little history lesson is needed. In the year 610 Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Roman Pantheon to the Blessed Virgin Mary and to all Christian martyrs and set aside a day in their honor. That date, May 13, coincided with the Lemuria festival, a pagan Roman celebration intended to satisfy the restless dead. A century later, this Day of All Saints was moved to Nov. 1. "All Hallows," "Halloween" eventually joined the stable of popular designations for the time in the Church's liturgical calendar when the Church commemorates its saints (or hallowed ones). The November date was providentially close to the feast celebrated by pagan Celts in honor of their druid "lord of the dead" the god Samhain. Bonfires would be built, gourds would be carved into lanterns and treats would be set out for the dead. Realizing the value of incorporating non-evil pagan practices into Christian faith, which was nothing new, the Church allowed Christians to continue these customs as a way for us to pass on the faith. If these non-evil customs should help us remember to set aside a time to pray for the dead. -

Nutrition Services Key Personnel Monthly Report

Office of Public Health Report to the DD Council December 2015 Agency Changes: The Office of Public Health is saddened by the resignations of Dr. Takeisha Davis, OPH Medical Director and Center for Community and Preventive Health Director, and Matthew Valliere, CCPH Deputy Director. Both have contributed enormously to OPH for many years, and both have accepted exciting CEO positions elsewhere. We look forward to new leadership in the new administration. Children’s Special Health Services: Family Resource Center (FRC) at Children’s Hospital: The FRC continues to provide community-based resource information to clients: September-November 2015: 280 total client encounters; 534 resource needs identified; 553 resource needs met. FRC staff continue to provide direct services in Botox, Spasticity, MD, neuromuscular, Down Syndrome, and Spina Bifida clinics at CHNOLA. The FRC youth liaison continues to provide community resource information to families in inpatient rehab. Outreach events at CHNOLA during this period: a. Broadcast 16th Annual Chronic Illness & Disability Conference from Baylor—15 attendees (October 1-2, 2015) b. CHNOLA Ice Cream Social—Rehab Family Reunion (9/25/15) c. Back to School Fair (10/13/15) The FRC maintains its Advisory Board, comprised mostly of parents of CYSHCN. The next Advisory Board meeting will be held April 2016. FRC staff continue to participate on local and CHNOLA boards and committees: Thuy Nguyen, FRC Parent Liaison, participates in the CHNOLA Commission on Accreditation on Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) Outcomes and Research Committees, providing family input. She is able to provide information to CHNOLA staff that will ultimately assist in getting resource information to families. -

Wedding Family Reunion Baby Shower Graduation Party Shower Anniversary Party Picnic Bridal Meeting Banquet Birthday

Wedding Family MeetingReunion • Engagement Baby Party Shower • Banquet Graduation • Sports Party • BridalParty Shower Shower • Graduation Anniversary Party Party Picnic Bridal Meeting Banquet Birthday Fam Baby Shower Wedding Family Reunion Baby Shower Graduation Party Shower Anniversary Party Picnic Bridal Meeting Banquet Birthday Fam Wedding Family Wedding Family Reunion Baby Shower Graduation Party Shower Anniversary Party Picnic Bridal Meeting Banquet Birthday Fam ReunioWedding Family Reunion Picnic Graduation Party Baby Shower Wedding FamilyThe bestReunionLaurel place Baby to hold Shower your Graduation next event! Party Shower Anniversary Party Picnic Bridal Meeting Banquet Birthday Fam Wedding Family Reunion Picnic Graduation Party Baby Shower Wedding Family Reunion Baby Shower Graduation Party Shower Wedding Family Reunion Baby Shower Graduation Party Shower Anniversary Party Picnic Bridal Meeting Banquet Birthday Fam Baby Shower Wedding Family Reunion Baby Shower Graduation Party Shower Anniversary Party Picnic Bridal Meeting Banquet Birthday Fam Wedding Family Wedding Family Reunion Baby Shower Graduation Party Shower Anniversary Party Picnic Bridal Meeting Banquet Birthday Fam ReunioWedding Family Reunion Picnic Graduation Party Baby Shower Wedding Family Reunion Baby Shower Graduation Party Shower Anniversary Party Picnic Bridal Meeting Banquet Birthday City Fam of Laurel DepartmentWedding of Parks and FamilyRecreation ReunionFor rental Picnicinformation visitGraduation our website Party 8103 Sandy Spring Road • Laurel, MD 20707 Baby Shower Wedding(301) 725-7800 •Family (301) 725-1HIT • ( 301)Reunion 497-NEWS Babywww.cityof Shower laurel.org Graduationor call 301-725-5300 Party Bridal MeetingWedding Banquet • Family Reunion Birthday • Company PicnicFam • ReunioWeddingBaby Shower • Anniversary Family Party • Birthday Reunion ooking for a Place to Hold L Your Next Event? From the lake to the river to the pool we have a tremendous array of outdoor and indoor facilities. -

11Th Annual Office Gynecology Conference

#1437 th 24 Annual Fall Conference on Challenges in Taking Care of the High Risk Pregnancy A Non-Profit Corporation for Sonesta Resort Hilton Head Island Continuing Medical & Nursing Education Hilton Head Island, South Carolina ~ November 15-18, 2017 TOUR OPTIONS Dear Registrant: This packet gives you information regarding optional tours during your stay on Hilton Head Island. SONESTA RESORT CONCIERGE DESK For tour information and to make reservations, please call the Sonesta Resort at 843-842-2400 and ask to speak with the Concierge or send an email to [email protected]. They have many tour suggestions they can provide. You can make reservations when you arrive; however, we suggest making reservations prior to arrival as some tours may sell out. TOURS ON HILTON HEAD ISLAND o VAGABOND CRUISE FROM HARBOUR TOWN Please refer to the flyer on the following page for Vagabond Cruises. Please visit their website at www.vagabondcruise.com. Reservations can be made up to two weeks in advance and are not required for dolphin cruises. Please call 843-363-9026 and let them know you’re with Symposia Medicus to receive a $5 per person discount. The group discount is not valid with other additional discounts, on holidays, or during special event cruises. These tours DO NOT include transportation; if you have a rental car, parking is available at different locations near the cruise departure location (149 Lighthouse Road - part of the Sea Pines Plantation). Sea Pines Plantation charges approximately $6 per car gate pass fee to enter and park. The concierge can help you arrange a taxi for approximately $20 each way. -

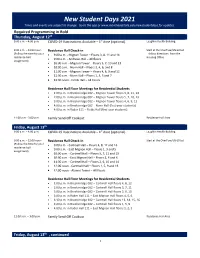

New Student Days 2021 Times and Events Are Subject to Change

New Student Days 2021 Times and events are subject to change. Go to the app or www.moreheadstate.edu/newstudentdays for updates. Required Programming in Bold Thursday, August 12th 9:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. COVID-19 Vaccinations Available – 1st dose (optional) Laughlin Health Building 9:00 a.m. – 12:00 noon Residence Hall Check-in Start at the Overflow/US 60 Lot (Follow the time for your • 9:00 a.m. - Mignon Tower – Floors 3, 8, 11 and 14 – follow directions from the residence hall Housing Office • 9:00 a.m. - Andrews Hall – All floors assignment) • 10:00 a.m. - Mignon Tower – Floors 5, 7, 10 and 13 • 10:00 a.m. - Nunn Hall – Floors 2, 4, 6, and 8 • 11:00 a.m. - Mignon Tower – Floors 4, 6, 9 and 12 • 11:00 a.m. - Nunn Hall – Floors 1, 3, 5 and 7 • 12:00 noon - Fields Hall – All Floors Residence Hall Floor Meetings for Residential Students • 1:00 p.m. in Breckinridge 002 – Mignon Tower floors 3, 8, 11, 14 • 2:00 p.m. in Breckinridge 002 – Mignon Tower floors 5, 7, 10, 13 • 3:00 p.m. in Breckinridge 002 – Mignon Tower floors 4, 6, 9, 12 • 4:00 p.m. in Breckinridge 002 – Nunn Hall (first-year students) • 4:00 p.m. in Rader 111 – Fields Hall (first-year students) 11:00 a.m.- 3:00 p.m. Family Send-Off Cookout Residence Hall Area Friday, August 13th 9:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. COVID-19 Vaccinations Available – 1st dose (optional) Laughlin Health Building 9:00 a.m. -

Enjoy an Evening of Ballroom Dancing! by CAROLYN BRENNEMAN Encourage Seniors of All Ages to to 82 Years

Serving AUGUSTA & the CSRA Information For Ages 50 PLUS! EnjoyEnjoy anan EveningEvening ofof BallroomBallroom Dancing!Dancing! July 2011 Vol. 25, No. 7 StoryStory onon PagePage 66 Page 2 • July 2011 • Senior News • Augusta Taking Care Help older relatives enjoy summer safely by LISA M. PETSCHE health and keep him or her to take some beverages along your vehicle is not air condi- comfortable during the dog whenever you go out. Water is tioned, time your trips and plan days of summer: best, but if he or she isn’t a water your routes to avoid traffic con- Attention caregivers: sum- • Before planning your day, lis- drinker, try vegetable juice or gestion. Before getting in, open mer sun, heat and smog can be ten to the weather forecast for diluted fruit juice. Avoid caf- all the windows or doors to let harmful to your older relative’s temperature, humidity level and feinated and alcoholic beverages. heat escape. Never leave your already fragile air quality reading If your relative is on fluid restric- relative in your vehicle while health. • Stay indoors and keep win- tions or a special diet, consult doing errands, as heat can quick- At tins time dows closed when smog alerts with the doctor before making ly build up to a dangerous level of year, the ele- are issued. any changes. during the summer months. ments bring • Close blinds and curtains to • For cooking, use a microwave • Whenever you go out, see to increased risk for block the sun’s powerful summer oven, toaster oven or barbecue it that your relative is wearing Lisa Petsche certain problems, rays. -

Reflections in Poetry and Prose 2018

5T 2 H AN NIV ERSARY Reflections in poetry and prose 2018 UNITED FEDERATION OF TEACHERS • RETIRED TEACHERS CHAPTER INTRODUCTION It is always a pleasure to experience the creativity, insights and talents of our re- tired members, and this latest collection of poems and writings provides plenty to enjoy! Being a union of educators, the United Federation of Teachers knows how im- portant it is to embrace lifelong learning and engage in artistic expression for the pure joy of it. This annual publication highlights some gems displaying the breadth of intellectual and literary talents of some of our retirees attending classes in our Si Beagle Learning Centers. We at the UFT are quite proud of these members and the encouragement they receive through the union’s various retiree programs. I am happy to note that this publication is now celebrating its 25th anniversary as part of a Retired Teachers Chapter tradition reflecting the continuing interests and vitality of our retirees. The union takes great pride in the work of our retirees and expects this tradition to continue for years to come. Congratulations! Michael Mulgrew President, UFT Welcome to the 25th volume of Reflections in Poetry and Prose. Reflections in Poetry and Prose is a yearly collection of published writings by UFT retirees enrolled in our UFTWF Retiree Programs Si Beagle Learning Center creative writing courses and retired UFT members across the country. We are truly proud of Reflections in Poetry and Prose and of the fine work our retirees do. Many wonderful, dedicated people helped produce this volume of Reflections in Poetry and Prose. -

Ice Cream Days Sesquicentennial

• LE MARS • Ice Cream Days AND Sesquicentennial June 12-16, 2019 On Your Own Time: Downtown Scavenger Hunt installed on over 42 buildings in ten alleys. Brochures are While shopping, eating or simply enjoying one of the Ice available at the Chamber of Commerce, City Hall and the Cream Days’ events in downtown Le Mars, participate in Visitor’s Bureau. a family-friendly, self-paced scavenger hunt showcasing downtown buildings significant in Le Mars’ history. Monday - Saturday: 9 a.m. - 10 p.m. Pick up the scavenger hunt sheets at the Chamber of Sunday: Noon - 10 p.m. Commerce, City Hall, Visitor’s Bureau or Ice Cream Parlor. Ice Cream Parlor, 115 Central Avenue NW Return your completed sheets to the Ice Cream Parlor by Ice Cream Days isn’t complete without a visit to The Sunday evening when all correct sheets will be entered Parlor for Blue Bunny Ice Cream! Your visit will be even in a prize drawing. The Downtown Scavenger Hunt was more exciting this year with the expanded, reimagined created by the Youth on Main Street high school students. Parlor! The new rooftop seating, theatre experience, and interactive exhibits showing a peek at how ice On Your Own Time: Historic City Driving Tour cream is made in the Ice Cream Capital of the World© Discover Le Mars’ 150-year history through a self-guided are all must-sees! Check us out online at facebook.com/ driving tour of our community. You will visit locations, BlueBunnyIceCreamParlor for hours and info. buildings, sites, people and events significant to Le Mars. -

Notes on the Fort Worth Family Reunion 2021 Reunion

E L I F I D T Y H O R N O L O A R WORLD WARII • KOREA • VIETNAM • PEACETIME • SOUTHWEST ASIA V COLD WAR • WARONTERRORISM • AFGHANISTAN • IRAQ VOL. 71, NO. 1, JAN -MARCH 2021 NOTES ON THE FORTWORTH FAMILY REUNION 2021 REUNION INFORMATION The2021 Reunion will be in Fort Worth,Texas, September 13 –19, 2021 at the Radisson Hotel Fort Worth North, 2540 Meachum Blvd. Fort Worth, Texas 76106. Theroom rate is $119/night +taxes, including acomplimentary buffet breakfast and complimentary parking. For reservations call 817-625-9911 Bell Helicopter (now known as BellFlight or just Bell) was like apartner to us in Vietnam. They had a variety of models: HueyCobra/Cobra, SeaCobra, Sioux, Kiowa, Iroquois (Huey), Huey Cobra/Frog, that all served in Vietnam. In today’sMarine Corps, abig part of aviation is the Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey,aswell as the Bell AH-1W Super Cobra. Since they are aDOD contractor,wewill need DOD clearance. When you select this event, make sure you fill in the DOD information. To continue the aviation part of this Reunion, we go from Bell to the Fort Worth Aviation Museum. We will get abox lunchonthe bus and eat at the museum when we getthere. The FortWorthAviation Museum has many aircraft that youwill be familiarwith,but one is of particular importance to the Executive Director of the museum, aformer Marine pilot. Some of you may know the OV-10A Bronco that served in many capacities in Vietnam such as Recon, observation, forward air control, helicopter escort, gunfire spotting, etc. as it first arrived in Vietnam on July 6, 1968.