Issues of Cultural Heritage Surrounding the Destruction and Possible Rebuilding of the Bamiyan Buddhas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 86/2013 of 31 January 2013 Implementing Article 11(4)

Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 86/2013 of 31 January 2013 implementing Article 11(4)... 1 ANNEX Document Generated: 2021-01-28 Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 86/2013. (See end of Document for details) ANNEX I. The entry in the list set out in Annex I to Regulation (EU) No 753/2011 for the person below shall be replaced by the entry set out below. A. Individuals associated with the Taliban Badruddin Haqqani (alias Atiqullah). Address: Miram Shah, Pakistan. Date of birth: approximately 1975-1979. Place of birth: Miramshah, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Other information: (a) operational commander of the Haqqani Network and member of the Taliban shura in Miram Shah, (b) has helped lead attacks against targets in south-eastern Afghanistan, (c) son of Jalaluddin Haqqani, brother of Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani and Nasiruddin Haqqani, nephew of Khalil Ahmed Haqqani. (d) Reportedly deceased in late August 2012. Date of UN designation:11.5.2011. Additional information from the narrative summary of reasons for listing provided by the Sanctions Committee: Badruddin Haqqani is the operational commander for the Haqqani Network, a Taliban-affiliated group of militants that operates from North Waziristan Agency in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan. The Haqqani Network has been at the forefront of insurgent activity in Afghanistan, responsible for many high-profile attacks. The Haqqani Network’s leadership consists of the three eldest sons of its founder Jalaluddin Haqqani, who joined Mullah Mohammed Omar's Taliban regime in the mid-1990s. Badruddin is the son of Jalaluddin and brother to Nasiruddin Haqqani and Sirajuddin Haqqani, as well as nephew of Mohammad Ibrahim Omari and Khalil Ahmed Haqqani. -

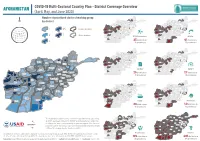

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

IMAGES of POWER: BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE (Buddhism on the Silk Road) BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE on the Silk Road

IMAGES OF POWER: BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE (Buddhism on the Silk Road) BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE on the Silk Road Online Links: Bamiyan Buddhas: Should they be rebuit? – BBC Afghanistan Taliban Muslims destroying Bamiyan Buddha Statues – YouTube Bamiyan Valley Cultural Remains – UNESCO Why the Taliban are destroying Buddhas - USA Today 1970s Visit to Bamiyan - Smithsonian Video Searching for Buddha in Afghanistan – Smithsonian Seated Buddha from Gandhara - BBC History of the World BUDDHIST ART and ARCHITECTURE of China Online Links: Longmen Caves - Wikipedia Longmen Grottoes – Unesco China The Longmen Caves – YouTube Longmen Grottoes – YouTube Lonely Planet's Best In China - Longmen China – YouTube Gandhara Buddha - NGV in Australia Meditating Buddha, from Gandhara , second century CE, gray schist The kingdom of Gandhara, located in the region of presentday northern Pakistan and Afghanistan, was part of the Kushan Empire. It was located near overland trade routes and links to the ports on the Arabian Sea and consequently its art incorporated Indian, Persian and Greco- Roman styles. The latter style, brought to Central Asia by Alexander the Great (327/26–325/24 BCE) during his conquest of the region, particularly influenced the art of Gandhara. This stylistic influence is evident in facial features, curly hair and classical style costumes seen in images of the Buddha and bodhisattvas that recall sculptures of Apollo, Athena and other GaecoRoman gods. A second-century CE statue carved in gray schist, a local stone, shows the Buddha, with halo, ushnisha, urna, dressed in a monk’s robe, seated in a cross-legged yogic posture similar to that of the male figure with horned headdress on the Indus seal. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Annex to Financial Sanctions: Afghanistan 01.02.21

ANNEX TO NOTICE FINANCIAL SANCTIONS: AFGHANISTAN THE AFGHANISTAN (SANCTIONS) (EU EXIT) REGULATIONS 2020 (S.I. 2020/948) AMENDMENTS Deleted information appears in strikethrough. Additional information appears in italics and is underlined. Individuals 1. ABBASIN, Abdul Aziz DOB: --/--/1969. POB: Sheykhan village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan a.k.a: MAHSUD, Abdul Aziz Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref): AFG0121 (UN Ref): TAi.155 (Further Identifying Information): Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for nonAfghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here. Listed On: 21/10/2011 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 01/02/2021 Group ID: 12156. 2. ABDUL AHAD, Azizirahman Title: Mr DOB: --/--/1972. POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Nationality: Afghan National Identification no: 44323 (Afghan) (tazkira) Position: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref): AFG0094 (UN Ref): TAi.121 (Further Identifying Information): Belongs to Hotak tribe. Review pursuant to Security Council resolution 1822 (2008) was concluded on 29 Jul. 2010. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/ Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here. Listed On: 23/02/2001 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 01/02/2021 Group ID: 7055. 3. ABDUL AHMAD TURK, Abdul Ghani Baradar Title: Mullah DOB: --/--/1968. -

Appendix 12 December 2018 CL13 2018 CV2018 04596

GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO FINANCIAL INTELLIGENCE UNIT MINISTRY OF FINANCE APPENDIX LISTING OF COURT ORDERS ISSUED BY THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO UNDER SECTION 22B (3) ANTI-TERRORISM ACT, CH. 12:07 CLAIM NO. CV 2018 - 04596: BETWEEN THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Claimant AND 1. MOHAMMAD also known as HASSAN also known as AKHUND; 2. ABDUL KABIR also known as MOHAMMAD JAN also known as A. KABIR; 3. MOHAMMED also known as OMAR also known a GHULAM NABI; 4. MUHAMMAD also known as TAHER also known as ANWARI also known as MOHAMMAD TAHER ANWARI also known as MUHAMMAD TAHIR ANWARI also known as MOHAMMAD TAHRE ANWARI also known as HAJI MUDIR; 5. SAYYED MOHAMMED also known as HAQQANI also known as SAYYED MOHAMMAD HAQQANI; 6. ABDUL LATIF also known as MANSUR also known as ABDUL LATIF MANSOOR also known as WALI MOHAMMAD; 7. SHAMS aIso known as UR-RAHMAN also known as ABDUL ZAHIR also known as SHAMSURRAHMAN also known as SHAMS-U-RAHMAN also known as SHAMSURRAHMAN ABDURAHMAN also known as SHAMS URRAHMAN SHER ALAM; 8. ATTIQULLAH also known as AKHUND; 9. AKHTAR also known as MOHAMMAD also known as MANSOUR also known as SHAH MOHAMMED also known as SERAJUDDIN HAQANI also known as AKHTAR MOHAMMAD MANSOUR KHAN MUHAM also known as AKHTAR MUHAMMAD MANSOOR also known as AKHTAR MOHAMMAD MANSOOR also known as NAIB IMAM; 10. MOHAMMAD NAIM also known as BARICH also known as KHUDAIDAD also known as MULLAH NAEEM BARECH also known as MULLAH NAEEM BARAICH also known as MULLAH NAIMULLAH also known as MULLAH NAIM BARER also known as MOHAMMAD NAIM (previously listed as) also known as MULLAH NAIM BARICH also known as MULLAHNAIM BARECH also known as MULLAH NAIM BARECH AKHUND also known as MULLAH NAEEM BARIC also known as NAIM BARICH also known as HAJI GUL MOHAMMED NAIM BARICH also known as GUL MOHAMMAD also known as HAJI GHUL MOHAMMAD also known as GUL MOHAMMAD KAMRAN also known as MAWLAWI GUL MOHAMMAD also known as SPEN ZRAE; 11. -

Afghanistan: Floods

P a g e | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Afghanistan: Floods DREF Operation n° MDRAF008 Glide n°: FL-2021-000050-AFG Expected timeframe: 6 months For DREF; Date of issue: 16/05/2021 Expected end date: 30/11/2021 Category allocated to the disaster or crisis: Yellow EPoA Appeal / One International Appeal Funding Requirements: - DREF allocated: CHF 497,700 Total number of people affected: 30,800 (4,400 Number of people to be 14,000 (2,000 households) assisted: households) 6 provinces (Bamyan, Provinces affected: 16 provinces1 Provinces targeted: Herat, Panjshir, Sar-i-Pul, Takhar, Wardak) Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Afghan Red Crescent Society (ARCS) has around 2,027 staff and 30,000 volunteers, 34 provincial branches and seven regional offices all over the country. There will be four regional Offices and six provincial branches involved in this operation. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: ARCS is working with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) and International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) with presence in Afghanistan. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: (i) Government ministries and agencies, Afghan National Disaster Management Authority (ANDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Committees (PDMCs), Department of Refugees and Repatriation, and Department for Rural Rehabilitation and Development. (ii) UN agencies; OCHA, UNICEF, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Organization for Migration (IOM) and World Food Programme (WFP). (iii) International NGOs: some of the international NGOs, which have been active in the affected areas are including, Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees (DACAAR), Danish Refugee Council (DRC), International Rescue Committee, and Care International. -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 7

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 7 Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Home > Research Program > Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) respond to focused Requests for Information that are submitted to the Research Directorate in the course of the refugee protection determination process. The database contains a seven-year archive of English and French RIRs. Earlier RIRs may be found on the UNHCR's Refworld website. 30 April 2013 AFG104294.E Afghanistan: Human rights abuses committed by the Afghanistan National Army and security forces (1989-2009) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa 1. Political Situation (1989-2009) Political Handbook of the World 2012 (PHW) says that, from 1987 until April 1992, Mohammad Najibullah was the president of the Republic of Afghanistan (2012, 3). President-designate Sebghatullah Mojaheddi proclaimed "the formation of an Islamic republic" in April 1992 (PHW 2012, 3). According to the Human Security Report Project, an independent research centre in Vancouver (HSRP n.d.b.), the state was referred to as the Islamic State of Afghanistan (ISA) (HSRP n.d.a). Burhanuddin Rabbani took over as president of the ISA in June 1992 although "the new administration was never effectively implemented" (PHW 2012, 4). The Afghanistan Justice Project (AJP), an independent research and advocacy organization focusing on "war crimes and crimes against humanity" during the conflict in Afghanistan between 1978 and 2001 (AJP n.d.), reports similarly in its 2005 report entitled Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity: 1978-2001 that, following the proclamation of the ISA, the regime held limited power, while "rival factions" had established themselves in different parts of Kabul and its environs, and some other urban areas had a functioning administration (ibid. -

A Canter Some Dark Defile: Examining the Coalition Counter-Insurgency Strategy in Afghanistan

A Canter Some Dark Defile: Examining the Coalition Counter-Insurgency Strategy in Afghanistan Raspal Khosa A scrimmage in a Border Station— A canter down some dark defile— Two thousand pounds of education Drops to a ten-rupee jezail— The Crammer's boast, the Squadron's pride, Shot like a rabbit in a ride! These verses are from Rudyard Kipling’s evocative 1886 poem ‘Arithmetic on the Frontier’ that was published after the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-1880). Kipling speaks of the asymmetry of warfare between British soldiers who were educated and dispatched to the Indian sub-continent at great expense, and the Pushtun tribesmen that inhabit the wild borderlands between Afghanistan and what is now Pakistan, who although illiterate, are nonetheless skilled in the martial arts. Accounts of Great Game-era conflicts such as the Battle of Maiwand (1880) in Southern Afghanistan—where nearly 1,000 British and Indian Army troops were slaughtered by an overwhelming force of Afghan soldiers and ghazis (holy warriors)—have formed an image in the Western mind of the Pushtun as a fiercely independent actor who will defy attempts at external coercion or indeed strong central rule. A century later these perceptions were reinforced when the Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan’s tortuous internal politics, only to quit after 10 years of dogged resistance by Western-backed Mujahideen fighters. The present-day Taliban-dominated insurgency that has engulfed much of the south and east of Afghanistan is essentially being conducted by violent Pushtun Islamists on either side of the 2,430 km Afghanistan-Pakistan frontier. -

AFGHANISTAN MAP Central Region

Chal #S Aliabad #S BALKH Char Kent Hazrat- e Sultan #S AFGHANISTAN MAP #S Qazi Boi Qala #S Ishkamesh #S Baba Ewaz #S Central Region #S Aibak Sar -e Pul Islam Qala Y# Bur ka #S #S #S Y# Keshendeh ( Aq Kopruk) Baghlan-e Jadeed #S Bashi Qala Du Abi #S Darzab #S #S Dehi Pul-e Khumri Afghan Kot # #S Dahana- e Ghori #S HIC/ProMIS Y#S Tukzar #S wana Khana #S #S SAMANGAN Maimana Pasni BAGHLAN Sar chakan #S #S FARYAB Banu Doshi Khinjan #S LEGEND SARI PUL Ruy-e Du Ab Northern R#S egion#S Tarkhoj #S #S Zenya BOUNDARIES Qala Bazare Tala #S #S #S International Kiraman Du Ab Mikh Zar in Rokha #S #S Province #S Paja Saighan #S #S Ezat Khel Sufla Haji Khel District Eshqabad #S #S Qaq Shal #S Siyagerd #S UN Regions Bagram Nijrab Saqa #S Y# Y# Mahmud-e Raqi Bamyan #S #S #S Shibar Alasai Tagab PASaRlahWzada AN CharikarQara Bagh Mullah Mohd Khel #S #S Istalif CENTERS #S #S #S #S #S Y# Kalakan %[ Capital Yakawlang #S KAPISA #S #S Shakar Dara Mir Bacha Kot #S Y# Province Sor ubi Par k- e Jamhuriat Tara Khel BAMYAN #S #S Kabul#S #S Lal o Sar Jangal Zar Kharid M District Tajikha Deh Qazi Hussain Khel Y# #S #S Kota-e Ashro %[ Central Region #S #S #S KABUL #S ROADS Khord Kabul Panjab Khan-e Ezat Behsud Y# #S #S Chaghcharan #S Maidan Shar #S All weather Primary #S Ragha Qala- e Naim WARDAK #S Waras Miran Muhammad Agha All weather Secondary #S #S #S Azro LOGAR #S Track East Chake-e Wnar dtark al RegiKolangar GHOR #S #S RIVERS Khoshi Sayyidabad Bar aki Bar ak #S # #S Ali Khel Khadir #S Y Du Abi Main #S #S Gh #S Pul-e Alam Western Region Kalan Deh Qala- e Amr uddin -

LAND RELATIONS in BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 Village Case Study

Case Studies Series LAND RELATIONS IN BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 village case study Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit By Liz Alden Wily February 2004 Funding for this study was provided by the European Commission, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland. © 2004 The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). All rights reserved. This case study report was prepared by an independent consultant. The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of AREU. About the Author Liz Alden Wily is an independent political economist specialising in rural property issues and in the promotion of common property rights and devolved systems for land administration in particular. She gained her PhD in the political economy of land tenure in 1988 from the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Since the 1970s, she has worked for ten third world governments, variously providing research, project design, implementation and policy guidance. Dr. Alden Wily has been closely involved in recent years in the strategic and legal reform of land and forest administration in a number of African states. In 2002 the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit invited Dr. Alden Wily to examine land ownership problems in Afghanistan, and she continues to return to follow up on particular concerns. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation that conducts and facilitates action-oriented research and learning that informs and influences policy and practice. AREU also actively promotes a culture of research and learning by strengthening analytical capacity in Afghanistan and by creating opportunities for analysis, thought and debate.