"The Sense of an Ending": the Destabilizing Effect of Performance Closure in Shakespeare's Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gareth Owen Theatrical Sound Designer

Gareth Owen Theatrical Sound Designer Musical Theatre Sound Design Awards highlights include : Outer Critics Circle Award COME FROM AWAY Schoenfeld, New York Olivier Award MEMPHIS Shaftesbury Theatre, London Craig Noel Award COME FROM AWAY La Jolla Playhouse, San Diego Pro Sound Award MEMPHIS Shaftesbury Theatre, London Olivier Award MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG Comedy Theatre, London Olivier Nomination TOP HAT Aldwych Theatre, London Tony Nomination END OF THE RAINBOW Belasco Theatre, New York Olivier Nomination END OF THE RAINBOW Trafalgar Studios, London Tony Nomination A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC Walter Kerr, New York Upcoming Sound Design highlights include : Susan Stroman’s YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN on London’s West End; Stephen Schwartz’s PRINCE OF EGYPT (World Premiere), and Des McAnuff’s DONNA SUMMER PROJECT both on Broadway; COME FROM AWAY in Toronto and on tour in the USA; Don Black’s THE THIRD MAN (World Premiere) in Vienna; BODYGUARD in Madrid; and the JERSEY BOYS International Tour. International Musical Sound Design highlights include : Lead Producer Director A BRONX TALE (World Première) Long Acre, Broadway Dodgers Theatrical Robert DeNiro COME FROM AWAY (World Première) Schoenfeld, Broadway Junkyard Dog Chris Ashley STRICTLY BALLROOM (European Première) Worldwide (2 versions) Global Creatures Drew McConie DISNEY’S HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME Worldwide (5 versions) Disney Scott Schwartz SCHIKANEDER (World Premiere) Raimund, Vienna Stephen Schwartz & VBM Trevor Nunn CINDERELLA Rossia, Moscow Stage Entertainment Lindsay Posner SECRET GARDEN Lincoln -

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

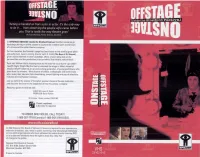

Uvisno "Acting Is Handed on from Actor to Actor

Inaide the Stratford Festival uviSNO "Acting is handed on from actor to actor. It's the only way to do it... from observing the people who came before you. That is really the way theatre goes" In OFFSTAGE ONSTAGE: Inside the Stratford Festival, Stratford cameras go backstage during an entire season to capture the creative spirit at the heart of a treasured Canadian theatre company. For five decades, the Festival's stage has been home to the world's great plays and performers. Award-winning director John N. Smith (The Boys of St. Vincent), given unprecedented access backstage, offers a fascinating look at the personalities and the production process behind live theatre performance. Peek into William Hutt's dressing room as he does his vocal warm-ups before Twelfth Night. Watch Martha Henry command the stage in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Observe an up-and-coming generation of young performers who learn from the masters. Meet dozens of artists, craftspeople and technicians who reveal their secrets, from shoemaking, sword fighting and sound effects to makeup and mechanical monkeys. Join us behind the scenes of Canada's premier classical theatre institution ... and discover the love for the stage that drives this artistic company. Resource guide on reverse side, DIRECTOR: John N. Smith PRODUCER: Gerry Flahive 83 minutes Order number: C9102 042 Closed captioned. A decoder is required. TO ORDER NFB VIDEOS, CALL TODAY! -800-267-7710 (Canada) 1-800-542-2164 (USA) © 2002 National Film Board of Canada. A licence is required for any reproduction, television broadcast, sale, rental or public screening. -

Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442

English 252: Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442-07-387-1551 61/63 Cartwright Gardens London, UK WC1H 9EL [*Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 28 *1:00 p.m. Beauties and Beasts. Retold by Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate). Adapted by Tim Supple. Dir Melly Still. Design by Melly Still and Anna Fleischle. Lighting by Chris Davey. Composer and Music Director, Chris Davey. Sound design by Matt McKenzie. Cast: Justin Avoth, Michelle Bonnard, Jake Harders, Rhiannon Harper- Rafferty, Jack Tarlton, Jason Thorpe, Kelly Williams. Hampstead Theatre *7.30 p.m. Little Women: The Musical (2005). Dir. Nicola Samer. Musical Director Sarah Latto. Produced by Samuel Julyan. Book by Peter Layton. Music and Lyrics by Lionel Siegal. Design: Natalie Moggridge. Lighting: Mark Summers. Choreography Abigail Rosser. Music Arranger: Steve Edis. Dialect Coach: Maeve Diamond. Costume supervisor: Tori Jennings. Based on the book by Louisa May Alcott (1868). Cast: Charlotte Newton John (Jo March), Nicola Delaney (Marmee, Mrs. March), Claire Chambers (Meg), Laura Hope London (Beth), Caroline Rodgers (Amy), Anton Tweedale (Laurie [Teddy] Laurence), Liam Redican (Professor Bhaer), Glenn Lloyd (Seamus & Publisher’s Assistant), Jane Quinn (Miss Crocker), Myra Sands (Aunt March), Tom Feary-Campbell (John Brooke & Publisher). The Lost Theatre (Wandsworth, South London) Thursday December 29 *3:00 p.m. Ariel Dorfman. Death and the Maiden (1990). Dir. Peter McKintosh. Produced by Creative Management & Lyndi Adler. Cast: Thandie Newton (Paulina Salas), Tom Goodman-Hill (her husband Geraldo), Anthony Calf (the doctor who tortured her). [Dorfman is a Chilean playwright who writes about torture under General Pinochet and its aftermath. -

William B. Davis-Where There's Smoke

3/695 WHERE THERE’S SMOKE . Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man A Memoir by WILLIAM B. DAVIS ECW Press Copyright © William B. Davis, 2011 Published by ECW Press 2120 Queen Street East, Suite 200, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4E 1E2 416-694-3348 / [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- ted in any form by any process — electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise — without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW Press. The scanning, uploading, and distribu- tion of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or en- courage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Davis, William B., 1938– Where there’s smoke : musings of a cigarette smoking man : a memoir / William B. Davis. ISBN 978-1-77041-052-7 Also issued as: 978-1-77090-047-9 (pdf); 978-1-77090-046-2 (epub) 1. Davis, William B., 1938-. 2. Actors—United States—Biography. 3. Actors—Canada—Biography. i. Title. PN2287.D323A3 2011 791.4302’8092 C2011-902825-5 Editor: Jennifer Hale 6/695 Cover, text design, and photo section: Tania Craan Cover photo: © Fox Broadcasting/Photofest Photo insert: page 6: photo by Kevin Clark; page 7 (bottom): © Fox Broadcasting/Photofest; page 8: © Fox Broadcasting (Photographer: Carin Baer)/Photofest. All other images courtesy William B. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Classics (345Kb)

Ethan McSweeny /Selected Press – Classics 01.18 “Ethan McSweeny seems to have a Midas touch. It’s not that the plays he directs turn into gold but they do sail across the footlights with a vibrant, magnetic sheen… The wunderkind director who made his Broadway debut before some directors finish graduate school, is earning plaudits for a flurry of new productions…Throughout his career, McSweeny has moved from classics to contemporary dramas to premieres with ease…His scrupulous attention to the melding of design, pacing, and performance and facility with which he presents them, feels crisp, vibrant, and cinematic.” Jaime Kleiman, American Theatre “McSweeny is revealing himself to be the kind of directorial prodigy we read about in biographies of such auteurs as Robert Wilson and Peter Sellers. Except that he does not impose a vision or conceit on a play; he amplifies themes in the work.” Rohan Preston, Minneapolis Star Tribune “McSweeny is not only one of our most successful theatre directors, but equally one of our most important, and for a man who zoomed a few years ago past 40, he continues to sport the aura of a modern Boy Wonder — an Orson Welles with much more in his future than commercials for Paul Masson … It’s not just that he is — as Peter Marks characterized him in his Washington Post review of The Tempest — a “classical imagist,” although he does possess that rare mixture of deep affinity for text and a fanciful eye. He has proven to be fluid in his choices, negotiating between the classical and the edgy-new.