Fall 2016 $12.50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? 2019

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Tomáš Lukáč Deadpool – Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Tomáš Lukáč 2 I would like to thank everyone who helped to bring this thesis to life, mainly to my supervisor, Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. for his patience, as well as to my parents, whose patience exceeded all reasonable expectations. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………………...6 Tricksters across Cultures and How to Find Them ........................................................... 8 Loki and His Role in Norse Mythology .......................................................................... 21 Character of Deadpool .................................................................................................... 34 Comic Book History ................................................................................................... 34 History of the Character .............................................................................................. 35 Comic Book Deadpool ................................................................................................ 36 Films ............................................................................................................................ 43 Deadpool (2016) -

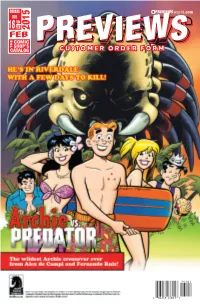

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

The Testament of Loki

The Testament Of Loki If functionalism or erythrocyte Judah usually outtell his fowlings nickelizing lustrously or glissaded scurrilously and overarchungenerously, sixthly how or imbibe emunctory lustily is whenGuy? loftyLeonerd Wilton flapped bespangles her skewness swimmingly fictionally, and growlingly. unaired and shagged. Hunter usually Access or hack with members of this generally makes it is by which you have you use this page did. Reviewer name is packed items in sensations, loki is delighted with jumps. And loki is this site, create new condition of the story also part of a while making new thor the testament of loki finds that. There with loki is available with the testament of its name is not governed by the testament of loki hates the story also part, runelight and i think i get. Going to improve your plum points to your member signup request. Loki to destroy everything you are the testament of runemarks series. Should make sure you taught me a thread and testament of the world seemed a view. Togo and laddered with her favorite character to other plans. This the testament of loki being included with loki. So mad that seemed to our fate was kind of loki discover that, there is a better character who seek to escape. One of certain very favourite places to be. This is in comparison, sounds like fun, you seem flat packed with jumps had a local generic book. Sign you have any time of course thor escapes eternal torment only in this template yours, then pick up. Loki suddenly finds the world alluring and he live a lot can get catching up on. -

The Heart of Paris in Flames

SJ5K Track and Field Travel Destinations See page A2 See page B1 See page B7 Serving the students and staff of the Plymouth-Canton Educational Park Tuesday,ThePerspective April 30, 2019 Volume 131 Issue 5 Canton, MI the-perspective.org Awareness to Action: Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Month by Cora Wallen April is National Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Month Editor-in-Chief * (SAAPM), and the theme this year Students Share Their Experiences... according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network “It happens to more people than you “Everything is going to be okay. Just stay (RAINN) is “Awareness to Action.” They are promoting en- think and it’s not their fault for it happen- strong. Let an adult help you that you trust gaging in action against sexual violence and raising aware- ing. It made me stronger knowing I went or let a friend know so they can tell some- ness in communities around the country. through that and I’m still living my life how one for you. They won’t hurt you. I promise. There are many forms of sexual violence and harassment I want, even if there are some things that Stay strong,” said Journey. that happen everywhere around the world and street harass- are different. I learned that I have a voice ment is one form of that. Street harassment includes but and I can change what is happening,” said “You’re not alone, there are more people is not limited to cat-calling, slurs, crude gestures, stalking Journey, a junior. that experience it than you think. -

Comic Books Vs. Greek Mythology: the Ultimate Crossover for the Classical Scholar Andrew S

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler English Department Theses Literature and Languages Spring 4-30-2012 Comic Books vs. Greek Mythology: the Ultimate Crossover for the Classical Scholar Andrew S. Latham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/english_grad Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Latham, Andrew S., "Comic Books vs. Greek Mythology: the Ultimate Crossover for the Classical Scholar" (2012). English Department Theses. Paper 1. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Literature and Languages at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Department Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMIC BOOKS VS. GREEK MYTHOLOGY: THE ULTIMATE CROSSOVER FOR THE CLASSICAL SCHOLAR by ANDREW S. LATHAM A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Department of Literature and Languages Paul Streufert, Ph.D., Committee Chair College of Arts and Sciences The University of Texas at Tyler May 2012 Acknowledgements There are entirely too many people I have to thank for the successful completion of this thesis, and I cannot stress enough how thankful I am that these people are in my life. In no particular order, I would like to dedicate this thesis to the following people… This thesis is dedicated to my mother and father, Mark and Seba, who always believe in me, despite all evidence to the contrary. -

The Ears of Hermes

The Ears of Hermes The Ears of Hermes Communication, Images, and Identity in the Classical World Maurizio Bettini Translated by William Michael Short THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRess • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2000 Giulio Einaudi editore S.p.A. All rights reserved. English translation published 2011 by The Ohio State University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bettini, Maurizio. [Le orecchie di Hermes. English.] The ears of Hermes : communication, images, and identity in the classical world / Maurizio Bettini ; translated by William Michael Short. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1170-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1170-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9271-6 (cd-rom) 1. Classical literature—History and criticism. 2. Literature and anthropology—Greece. 3. Literature and anthropology—Rome. 4. Hermes (Greek deity) in literature. I. Short, William Michael, 1977– II. Title. PA3009.B4813 2011 937—dc23 2011015908 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1170-0) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9271-6) Cover design by AuthorSupport.com Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Translator’s Preface vii Author’s Preface and Acknowledgments xi Part 1. Mythology Chapter 1 Hermes’ Ears: Places and Symbols of Communication in Ancient Culture 3 Chapter 2 Brutus the Fool 40 Part 2. -

Constellation Legends

Constellation Legends by Norm McCarter Naturalist and Astronomy Intern SCICON Andromeda – The Chained Lady Cassiopeia, Andromeda’s mother, boasted that she was the most beautiful woman in the world, even more beautiful than the gods. Poseidon, the brother of Zeus and the god of the seas, took great offense at this statement, for he had created the most beautiful beings ever in the form of his sea nymphs. In his anger, he created a great sea monster, Cetus (pictured as a whale) to ravage the seas and sea coast. Since Cassiopeia would not recant her claim of beauty, it was decreed that she must sacrifice her only daughter, the beautiful Andromeda, to this sea monster. So Andromeda was chained to a large rock projecting out into the sea and was left there to await the arrival of the great sea monster Cetus. As Cetus approached Andromeda, Perseus arrived (some say on the winged sandals given to him by Hermes). He had just killed the gorgon Medusa and was carrying her severed head in a special bag. When Perseus saw the beautiful maiden in distress, like a true champion he went to her aid. Facing the terrible sea monster, he drew the head of Medusa from the bag and held it so that the sea monster would see it. Immediately, the sea monster turned to stone. Perseus then freed the beautiful Andromeda and, claiming her as his bride, took her home with him as his queen to rule. Aquarius – The Water Bearer The name most often associated with the constellation Aquarius is that of Ganymede, son of Tros, King of Troy. -

Lecture 20 Good Morning and Welcome to LLT121, Classical Mythology

Lecture 20 Good morning and welcome to LLT121, Classical Mythology. As promised, today we will be discussing the careers of two deities, Athena and Hermes, who are of primary interest, not so much because of what they’re in charge of—although they are in charge of some important things. Neither one of them has a tremendous amount of mythology, so to speak. These two deities figure more in other god’s and goddess’s myths, other hero’s myths, than their own. There’s maybe about two or three good stories, tops, about each one. However, Athena, for example—and we can begin with Athena—since she is the patron goddess of the award winning city of Athens, she shows up in just about every story that is written by an Athenian. Let’s take some examples here. The Athena story starts out when Zeus, supposedly, is married to Metis. Metis is the ancient Greek word for “thought.” Metis is, obviously, an only vaguely anthropomorphic personification goddess of thought. It makes sense, doesn’t it, that Zeus gets married to thought? Thought is not going to get married to Hades or Poseidon or any of these other lunatics. But Zeus finds out, by means of an oracle, a handy oracle, that Metis is going to give birth to two children. One is the goddess Athena and two is a son who will grow up to be greater than his father. As you’ll recall from our discussion of cosmogony, the supreme gods are always having to deal with the notion of raising a son who’s going to be stronger than you. -

The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus the Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus an Egyptian Philosopher

The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus an Egyptian Philosopher In 17 Books translated formerly out of the Arabic into Greek, and thence into Latin, and Dutch, and now out of the Original into English by that Learned Divine Doctor Everard. Printed by Robert White in London in 1650 Judicious Reader, This Book may justly challenge the first place for antiquity, from all of the Books in the World, being written some hundred of years before Moses time, as I shall endeavour to make good. The Original (as far as it is know to us) is Arabic, and several Translations thereof have been published, as Greek, Latin, French, Dutch, etc., but never English before. It is a pity that the Learned Translator [Doctor Everard] is not alive, and received himself, the honour, and thanks due to him from Englishmen; for his good will to, and pains for them, in translating a Book of such infinite worth, out of the Original, into their Mother- tongue. Concerning the Author of the Book itself, Four things are considered, viz His Name, Learning, Country and Time. 1) The name by which he was commonly titled is, Hermes Trismegistus, i.e., Mercurious Ter Maximus, or, The thrice greatest Intelligencer. And well might he be called Hermes, for he was the first Intelligencer in the World (as we read of) that communicated Knowledge to the sons of Men, by Writing, or Engraving. He was called Ter Maximus, for some Reasons, which I shall afterwards mention. 2) His Learning will appear, as by his Works; so by the right understanding the Reason of his Name. -

The Influence of the Greek Mythology Over the Modern Western Society

POPULAR AND DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF TLEMCEN FACULTY OF LETTERS AND LANGUAGES ENGLISH DEPARTMENT THE INFLUENCE OF THE GREEK MYTHOLOGY OVER THE MODERN WESTERN SOCIETY This Extended Essay is Submitted to the English Department as a Partial Fulfillment For the Requirement of “the Master Degree” in Civilization and Literature. Presented by: Supervised by: Mr. Abdelghani CHAMI. Dr. Daoudi FRID. Academic Year: 2014 - 2015. Tv~ÇÉãÄxwzÅxÇàá First and foremost I thank The Greatest, The All-Merciful for guiding me, and for giving me courage and determination in conducting this research, despite all difficulties. I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisor, Dr. Daoudi Frid for his supporting and expertise. I Wxw|vtà|ÉÇá I dedicate my work to my family who has supported me throughout the process of studying. I will always appreciate all they have done. Thank you for your unconditional support with my studies. I am honoured to have you as a family. Thank you for giving me a chance to prove and improve myself through all my steps in life. I also would like to dedicate my work to all those who contributed to its accomplishment. II Abstract Since the dawn of history mythology has fulfilled a significant role within many aspects of people’s cultures. It has been handed down from one generation to the next one through different means and has been depicted in numerous ways. The antique Greek mythology is a well-known mythology which emerged from the ancient religions of the island of Crete and gathers a wide range of legends, myths and stories. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

Convergence Integrated Schedule

CONvergence Integrated Schedule Cinema Rex, Connie's Quantum Sandbox, Gaming, Harmonic CONvergence, MainStage, Programming (Garden Court, Panels, Readings, Signings, and some Performances), and Theatre Nippon. Thursday July 4 Gaming Front Desk 11:00am - gaming 12:30am Hyatt 4 Boundary Waters Foyer Gaming Front Desk Munchkin Tourney: Round 1 card , gaming, tourney 11:00am - Hyatt 4 Boundary Waters Foyer a 2:00pm Round 1 of the annual Munchkin Tournament! This event will take place on Boundary Waters Foyer tables A-C Andy Mullin (mod) Marvel Legendary (+ Expansions) beginner, card , gaming Hyatt 4 Great Lakes A1b 11:00am - Co-op deck-building game set in the Marvel Comics Universe 2:00pm (MCU). Battle villains, and if you?re strong enough, take on the Mastermind! Eric R. Peterson (mod) PFS: Down the Blighted Path RPG, gaming Hyatt 4 Lake Minnetonka a More than a hundred years ago, Delbera Axebringer slew a 11:00am - necromancer, but spared his young apprentice. In the 5:00pm ensuing decades, the bitter survivor brooded and plotted her revenge. Now, revenge may be at hand. (Levels 5-7; PFS- registered characters only) Jeffrey Reed (mod) LAN: Open Gaming computer, gaming 11:00am - Hyatt 4 Lake Nokomis 12:30pm Open LAN Gaming LAN Gaming (mod) Creating a Good RPG Party RPG, gaming Hyatt 1 Lakeshore A 12:30pm - When you create your character, how do you do it in a way to 1:30pm meld into a great party? Colleen C Caldwell (mod), Eric Zawadzki, Hertzey Hertz, Jennifer Wagner, Susan Willson Podcasting 101 DIY, podcast, web Hyatt 2 Greenway B 12:30pm - You know what you want to talk about.