The Belhar Confession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affirm the Belhar? Yes, but Not As a Doctrinal Standard

AFFIRM THE BELHAR? YES, BUT NOT AS A DOCTRINAL STANDARD A Contribution to the Discussion in CRCNA John W. Cooper Professor of Philosophical Theology Calvin Theological Seminary August 2011 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 My Position and Involvement in the Discussion A Momentous Decision: Our Doctrinal Identity and Integrity The Burden of Proof WHY THE BELHAR CONFESSION CANNOT BE A DOCTRINAL STANDARD 6 Confusion about “Confession” The Belhar Confession Lacks the Content of a Doctrinal Standard The Belhar Confession is Doctrinally Ambiguous The Social Gospel? Liberation Theology? Is the Gospel at Stake: Status Confessionis? Biblical Justice or Liberation Ideology? CONSEQUENCES OF ADOPTING THE BELHAR AS A DOCTRINAL STANDARD 20 Adopting the Belhar Confession Would Compromise Our Confessional Integrity The Belhar Confession and Ecumenical Relations A Gift, or an Offer We Can’t Refuse? Do Racial Justice and Reconciliation Require Adoption of BC as a Confession? The Belhar, CRCNA Polity, and Denominational Unity Simple Majority? Conscientious Objection? WHY WE SHOULD AFFIRM THE BELHAR AS A TESTIMONY 27 The Basic Objection Neutralized Principled Decision or Political Compromise? Faithful Witness to Biblical Justice and Reconciliation Benefits for Ecumenical Relations and Racial Reconciliation in CRCNA Can We Make a Confession a Testimony? 2 AFFIRM THE BELHAR? YES, BUT NOT AS A DOCTRINAL STANDARD INTRODUCTION My Position and Involvement in the Discussion Synod 2009 recommended that Synod 2012 adopt the Belhar Confession [hereafter BC] as the CRCNA‟s fourth Form of Unity, that is, as a definitive doctrinal standard.1 I oppose that recommendation because I believe that the confessional and theological identity and integrity of the CRCNA are at stake. -

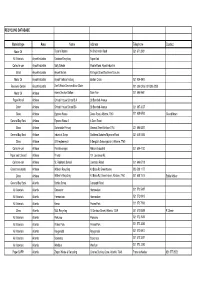

Special Schools

Province District Name PrimaryDisability Postadd1 PhysAdd1 Telephone Numbers Fax Numbers Cell E_Mail No. of Learners No. of Educators Western Cape Metro South Education District Agape School For The CP CP & Physical disability P.O. Box23, Mitchells Plain, 7785 Cnr Sentinel and Yellowwood Tafelsig, Mitchells Plain 213924162 213925496 [email protected] 213 23 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Alpha School Autism Spectrum Dis order P.O Box 48, Woodstock, 7925 84 Palmerston Road Woodstock 214471213 214480405 [email protected] 64 12 Western Cape Metro East Education District Alta Du Toit School Intellectual disability Private Bag x10, Kuilsriver, 7579 Piet Fransman Street, Kuilsriver 7580 219034178 219036021 [email protected] 361 30 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Astra School For Physi Physical disability P O Box 21106, Durrheim, 7490 Palotti Road, Montana 7490 219340155 219340183 0835992523 [email protected] 321 35 Western Cape Metro North Education District # Athlone School For The Blind Visual Impairment Private BAG x1, Kasselsvlei Athlone Street Beroma, Bellville South 7533 219512234 219515118 0822953415 [email protected] 363 38 Western Cape Metro North Education District Atlantis School Of Skills MMH Private Bag X1, Dassenberg, Atlantis, 7350 Gouda Street Westfleur, Atlantis 7349 0215725022/3/4 215721538 [email protected] 227 15 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Batavia Special School MMH P.O Box 36357, Glosderry, 7702 Laurier Road Claremont 216715110 216834226 -

Provisionally Adopt the Belhar Confession

COMMISSIONS 267 Synod in 2003 and met for the first time in November of that year. Since its organization, Michael Vandenberg has served as the commission’s moderator. As he ends his term of service on the commission and his leadership as moderator, the commission offers the fol- lowing resolution: R-79 Be it resolved that the two hundred and first General Synod of the Reformed Church in America expresses its appreciation for Michael Vandenberg’s four years of faithful service as moderator of the Commission on Christian Education and Discipleship. (ADOPTED) Report of the Commission on Christian Unity INTRODUCTION The General Synod is responsible for the RCA’s ecumenical relations (Book of Church Order, Chapter 1, Part V, Article 2, Section 5). In response to Christ’s prayer that we may all be one and to fulfill its constitutional responsibility, General Synod has constituted the Commission on Christian Unity (CCU) to oversee ecumenical commitments, to present an ecumenical agenda to the church, and to carry out ecumenical directives given by the General Synod. Since its creation in 1974 (MGS 1974, R-6, pp. 201-202) and adoption by General Synod in 1975 (MGS 1975, R-4, pp. 101-102) the CCU has served General Synod by coordinating a range of ecumenical involvements reaching all levels of mission in the RCA. CCU advises General Synod on ecumenical matters and communicates with other denominations, ecumenical councils, and interdenominational agencies. CCU educates the RCA on ecumenical matters and advocates for actions and positions consistent with the RCA’s confessions and ecumenical practices as outlined in “An Ecumenical Mandate for the Reformed Church in America,” which was adopted by General Synod in l996 (MGS 1996, R-1, p. -

Night at the Museum: the Secret Life of an Old Confession

Theology Matters A Publication of Presbyterians for Faith, Family and Ministry Vol 16 No 5 • Nov/Dec 2010 Night at the Museum: The Secret Life of an Old Confession by John L. Thompson The creation of a “Book of Confessions” in which the Westminster Confession of Faith is to be one among a number of confessional documents, and no longer the classic and regulative expression of Presbyterian theology, places it, to all practical intent, in a kind of theological museum, stripped of binding authority upon presbyters and regarded as irrelevant for today. 1 I’m embarrassed to confess that while I live and work the words of William Strong, quoted above, find a very close to the famous Norton Simon Museum in dismal fulfillment. But must this be the case? Pasadena, I have never been there. Oh, sure, I’ve driven by it many times. I’ve seen the outside of it on Our present BOC received its basic shape in 1965-67, in television when they broadcast the Rose Parade. I even the wake of a 1958 denominational merger that would know that it has some classic and valuable collections eventually see the Westminster Standards both trimmed of European and modern art, well worth a visit. But and supplemented by seven other confessional I’ve never been inside. documents—the Nicene Creed, the Apostles Creed, the Scots Confession, the Heidelberg Catechism, the It may be that I’m typical of many people—we are Second Helvetic Confession, the Barmen Declaration, proud of what our own towns and cities have to offer, and the still-to-be-written Confession of 1967 (C-67). -

Essential Tenets & Confessional Standards

Essential Tenets & Confessional Standards Essential Tenets Presbyterians have been of two minds about essential tenets. by recognizing and receiving His authoritative self- We recognize that just as there are some central and revelation, both in the infallible Scriptures of the Old and foundational truths of the gospel affirmed by Christians New Testaments and also in the incarnation of God the everywhere, so too there are particular understandings of the Son. We affirm that the same Holy Spirit who overshadowed gospel that define the Presbyterian and Reformed tradition. the virgin Mary also inspired the writing and preservation of All Christians must affirm the central mysteries of the faith, the Scriptures. The Holy Spirit testifies to the authority of and all those who are called to ordered ministries in a God’s Word and illumines our hearts and minds so that we Presbyterian church must also affirm the essential tenets of might receive both the Scriptures and Christ Himself aright. the Reformed tradition. Recognizing the danger in reducing the truth of the gospel to propositions that demand assent, we We confess that God alone is Lord of the conscience, but this also recognize that when the essentials become a matter freedom is for the purpose of allowing us to be subject always primarily of individual discernment and local affirmation, they and primarily to God’s Word. The Spirit will never prompt lose all power to unite us in common mission and ministry. our conscience to conclusions that are at odds with the Scriptures that He has inspired. The revelation of the Essential tenets are tied to the teaching of the confessions as incarnate Word does not minimize, qualify, or set aside the reliable expositions of Scripture. -

A Study of the Belhar Confession Contents

What is the Belhar Confession, and why does it matter? In this five-session study, learn how the Belhar was born, what it has to say about unity in the church, reconciliation between Christians, and justice in the world, and how it speaks to Christians everywhere. Visit www.crcna.org/belhar for accompanying videos and a 28-day devotional guide. A Study of the Belhar Confession Contents Introduction . .3 Important Dates in Belhar History �����������������������������������������������������������4 A Statement of Introduction by the CRC and RCA �������������������������������5 Original 1986 Accompanying Letter . .6 The Confession of Belhar ���������������������������������������������������������������������������9 A Study of the Using This Study Guide �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������13 Belhar Confession Session 1: The Belhar: What Is It? Why Does It Matter? . .17 Session 2: The Belhar Calls for Unity . .25 Session 3: The Belhar Calls for Justice . .33 Session 4: The Belhar Calls Us to Reconciliation . .43 by Susan Damon Session 5: What Shall We Do with This Gift? . .51 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations in this publication are from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®, © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. From the Heart of God: A Study of the Belhar Confession (Revised), © 2010, 2013, Christian Reformed Church in North America, 2850 Kala mazoo Ave. SE, Grand Rapids, MI 49560. All rights reserved. This study is updated from the 2010 version prepared for study of the Belhar Confes sion prior to Synod 2012’s deliberation whether to adopt the document as a confession of the Christian Reformed Church in North America. On June 12, 2012, synod adopted the Belhar Confession as an Ecumenical Faith Declaration. -

City of Cape Town Profile

2 PROFILE: CITY OF CAPETOWN PROFILE: CITY OF CAPETOWN 3 Contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction: Brief Overview ............................................................................. 8 2.1 Location ................................................................................................................................. 8 2.2 Historical Perspective ............................................................................................................ 9 2.3 Spatial Status ....................................................................................................................... 11 3. Social Development Profile ............................................................................. 12 3.1 Key Social Demographics ..................................................................................................... 12 3.1.1 Population ............................................................................................................................ 12 3.1.2 Gender Age and Race ........................................................................................................... 13 3.1.3 Households ........................................................................................................................... 14 3.2 Health Profile ....................................................................................................................... 15 3.3 COVID-19 ............................................................................................................................ -

A Quarterly Journal for Church Leadership

A Quarterly Journal for Church Leadership Volume 10 • Number 2 • Spring 2001 THE BELGIC CONFESSION OF FAITH AND THE CANONS OF DORDT ,I his powerful and willing divine care and turning-to-my good of which question 26 (in the Heidelberg Catechism) J ael7f( 1Beeiw speaks is God's providence, providentia Dei. Providence means not only to "foresee" but, according to the old trans lation, to "over-see." Dominus providebit: God will provide. Over and in all creatures in one way or another-quietly or he oldest of-the doctrinal standards of the Reformed actively, known or unknown, always according to the deci TIt Churches of the Netherlands is the Confession of Faith, sion of his wisdom-there is the "almighty and ever-pres most commonly known as the Belgic Confession, taken from ent power of God," the same power in all the differences the seventeenth-century Latin designation Confessio Belgica. and contradictions, light and dark sides, of creation. At this "Belgica" referred to the whole of the Low Countries, both point all arbitrary optimism and pessimism err in their north and south, today divided into the Netherlands and evaluation of creation because they believe that from a Belgium. Variant names for the Belgic Confession include the freely chosen standpoint they can judge how God's power Walloon Confession and the Netherlands· Confession. orders both sides in the direction of his final goal, in the The Confession's chief author was Guido de Bres (1522- service of his coming kingdom, looking forward to the rev 1567), a Reformed itinerant pastor. -

Cape Town's Residential Property Market Size, Activity, Performance

Public Disclosure Authorized Cape Town’s Residential Property Market Public Disclosure Authorized Size, Activity, Performance Public Disclosure Authorized Funded by A deliverable of Contract 7174693 Public Disclosure Authorized Submitted to the World Bank By the Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa January 2018 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the Centre for Affordable Housing in Africa, for the World Bank as part of its technical assistance programme to the Cities Support Programme of the South African National Treasury. The project team wishes to acknowledge the assistance of City of Cape Town officials who contributed generously of their time and knowledge to enable this work. Specifically, we are grateful to the engagement of Catherine Stone (Director: Spatial planning and urban design), Claus Rabe (Metropolitan Spatial Planning), Peter Ahmad (Manager: City Growth Management), Louise Muller (Director: Valuations), Llewellyn Louw (Head: Valuations Process & Methodology) and Emeraan Ishmail (Manager: Valuations Data & Business Systems). We also wish to acknowledge Tracy Jooste (Director of Policy and Research) and Paul Whelan (Directorate of Policy and Research), both of the Western Cape Department of Human Settlements; Yasmin Coovadia, Seth Maqetuka, and David Savage of National Treasury; and Yan Zhang, Simon Walley and Qingyun Shen of the World Bank; and independent consultants, Marja Hoek-Smit and Claude Taffin who all provided valuable comments. Project Team: Kecia Rust Alfred Namponya Adelaide Steedley Kgomotso -

Download the Belhar Study Guide

C o n t e n t s I n t ro d u c t i o n . .1 Belhar Confession . .3 Notes to Discussion Leaders . .7 Using This Study Guide . .9 G round Rules for Constructive Communication . .1 0 Session 1: Introduction to the Study Guide . .1 1 Session 2: All Creation Gro a n s . .1 3 Session 3: One God, One Churc h . .1 7 Session 4: The Belhar Speaks to Us . .2 3 Session 5: The Belhar Speaks of Justice . .2 9 Session 6: The Belhar Speaks of Reconciliation . .3 5 Session 7: The Belhar As a Call to Action . .4 1 Session 8: The Belhar As an Aff i rmation of Hope . .4 7 Session 9: What Shall We Do with This Gift? . .5 1 Appendix A: Readings . .5 5 Appendix B: Songs . .7 7 Appendix C: Worship Materials . .8 7 Appendix D: Dictionary of Relevant Te rm s . .9 1 Appendix E: Welcoming Diversity Inventory . .9 3 Appendix F: World Recipes . .9 7 To order, contact Faith Alive Christian Resources at (800) 333-8300 or [email protected]. REFORMED CHURCH IN AMERICA FOLLOWING CHRIST IN MISSION rca.org © 2006 REFORMED CHURCH PRESS Unity, Reconciliation, and Justice Introduction The Belhar Confession was first drafted in 1982 by the Dutch Reformed Mission Church in South Africa. It was adopted in 1986, and later it would become one of the standards of unity (along with the Belgic Confession, the Canons of Dort, and the Heidelberg Catechism) for the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa, a merger denomination of two South African Reformed churches. -

Unipin & Easypay Vendors List

Picknpay Supermarkets Region: Western Cape Bellville Cnr. Old Paarl & Voortrekker Str, Bellville 7530 Camps Bay Victoria Str, Camps Bay, 8001 Canal Walk Shop 129 Canal Walk Shopping Centre, Century City, 7441 Cape Gate Cape Gate Shopping Centre, c/o Okavango Drive and Debron Road, Brackenfell, 7560 Claremont Pick`n Pay Centre, Main Rd, Claremont, 7708 Constantia Cnr. Spaanschemacht & Main Roads, Constantia, 7800 Eerste Rivier Eerste Rivier Shopping Centre, Cnr. Main & Forest Dr., Eerste Rivier 7100 Gardens Mill Str, Gardens, 8001 Goodwood McDonald Str, Goodwood, 7460 Kenilworth Kenilworth Centre, Doncaster Str, Kenilworth, 7700 Long Beach Long Beach Mall Strore, Longboat Rd Milkwood Park Noordhoek, 7985 Melkbos Strand Birkenhead Shopping Centre Birkenhead & Otto du Plessis Drive, Melkbos Strand Milnerton Centrepoint Shopping Cenre, LoXton Rd, Milnerton, 7441 Mitchells Plain Town Centre, Mitchells Plain, 7785 Mountain Mill Shop 85, Mountain Mill Shopping Cntr, Mountain Mill Drive, Worcester Muizenberg Deury Rd, Price George Drive, Capricorn Park, Muizenberg, 7945 N1 City N1 City Shopping Centre, Vasco Blvd, Goodwood, 7460 Nyanga Nyanga Junction, Duinefontein Rd, Manenberg, 7764 Paarl Wanmakers Sentrum, Fabriek Str, Paarl, 7646 Paarl Cnr Kohler and Jones Streets, Drakenstein, Paarl, 7646 Pinelands Howard Centre, HowaRd Place, Pinelands, 7405 Plattekloof Gert Van Rooyen at Plattekloof Road, Plattekloof 021 558 6100 Prominade Cnr. Azburman and Morgenster Streets, Mitchell's Plain SeaPoint Adelphi Centre, Main Rd, Sea Point, 8001 Somerset Mall Somerset Mall, c/o R44 and N2, Somerset West, 7130 Somerset West Riverside Shopping Centre, Main Rd, Somerset West, 7130 Stellenbosch Stellmark, Bird Str, Stellenbosch, 7600 Strand Fagan Str, Strand, 7140 Sun Valley Cnr. NooRdhoek & Ou Kaapse Weg, NooRdhoek, 7975 Sunningdale Cnr. -

Material Type Area Name Address Telephone Contact RECYCLING DATABASE

RECYCLING DATABASE Material type Area Name Address Telephone Contact Motor Oil - Taylor's Motors 14 Chichester Road 021 671 2931 All Materials Airport Industria Rainbow Recycling Airport Ind Collect-a-can Airport Industria Solly Sebola Mobile Road, Airpot industria Metal Airport Industria Airport Metals Michigan Street/'Northern Suburbs Motor Oil Airport Industria Airport Vehicle Testing Boston Circle 021 934 4900 Recovery Centre Airport Industria Don't Waste Services Brian Slater 021 386 0206 / 021 386 0208 Motor Oil Athlone Adens Service Station Eden Ave 021 696 9941 Paper-Mondi Athlone Christel House School S A 38 Bamford Avenue Other Athlone Christel House School SA 38 Bamford Avenue 021 697 3037 Glass Athlone Express Waste Desre Road, Athlone, 7760 021 638 6593 Gerard Moen General Buy Back Athlone Express Waste 2 5 Desri Road Glass Athlone Garlandale Primary General Street Athlone 7764 021 696 8327 General Buy Back Athlone Industrial Scrap Southern Suburbs/'Mymona Road 021 448 5395 Glass Athlone LR Heydenreych 5 Bergzich Schoongezicht, Athlone, 7760 Collect-a-can Athlone Pen Beverages Athlone Industrial 021 684 4130 Paper and C/board Athlone Private 151 Lawrence Rd, Collect-a-can Athlone St. Raphaels School Lawrence Road 021 696 6718 Glass/ tins/ plastic Athlone Walkers Recycling 43 Brian Rd Greenhaven 083 508 1177 Glass Athlone Walker's Recycling 43 Brian Rd, Greenhaven, Athlone, 7760 021 638 1515 Eddie Walker General Buy Back Atlantis Berties Scrap Conaught Road All Materials Atlantis Grosvenor Hermeslaan 021 572 5487 All Materials