Audience Guide Written and Compiled by Jack Marshall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadway the BROAD Way”

MEDIA CONTACT: Fred Tracey Marketing/PR Director 760.643.5217 [email protected] Bets Malone Makes Cabaret Debut at ClubM at the Moonlight Amphitheatre on Jan. 13 with One-Woman Show “Broadway the BROAD Way” Download Art Here Vista, CA (January 4, 2018) – Moonlight Amphitheatre’s ClubM opens its 2018 series of cabaret concerts at its intimate indoor venue on Sat., Jan. 13 at 7:30 p.m. with Bets Malone: Broadway the BROAD Way. Making her cabaret debut, Malone will salute 14 of her favorite Broadway actresses who have been an influence on her during her musical theatre career. The audience will hear selections made famous by Fanny Brice, Carol Burnett, Betty Buckley, Carol Channing, Judy Holliday, Angela Lansbury, Patti LuPone, Mary Martin, Ethel Merman, Liza Minnelli, Bernadette Peters, Barbra Streisand, Elaine Stritch, and Nancy Walker. On making her cabaret debut: “The idea of putting together an original cabaret act where you’re standing on stage for ninety minutes straight has always sounded daunting to me,” Malone said. “I’ve had the idea for this particular cabaret format for a few years. I felt the time was right to challenge myself, and I couldn’t be more proud to debut this cabaret on the very stage that offered me my first musical theatre experience as a nine-year-old in the Moonlight’s very first musical Oliver! directed by Kathy Brombacher.” Malone can relate to the fact that the leading ladies she has chosen to celebrate are all attached to iconic comedic roles. “I learned at a very young age that getting laughs is golden,” she said. -

THE WIZARD of OZ an ILLUSTRATED COMPANION to the TIMELESS MOVIE CLASSIC by John Fricke and Jonathan Shirshekan with a Foreword by M-G-M “Munchkin” Margaret Pellegrini

THE WIZARD OF OZ AN ILLUSTRATED COMPANION TO THE TIMELESS MOVIE CLASSIC By John Fricke and Jonathan Shirshekan With a foreword by M-G-M “Munchkin” Margaret Pellegrini The Wizard of Oz: An Illustrated Companion to the Timeless Movie Classic is a vibrant celebration of the 70th anniversary of the film’s August 1939 premiere. Its U.S. publication coincides with the release of Warner Home Video’s special collector’s edition DVD of The Wizard of Oz. POP-CULTURE/ ENTERTAINMENT over the rainbow FALL 2009 How Oz Came to the Screen t least six times between April and September 1938, M-G-M Winkie Guards); the capture and chase by The Winkies; and scenes with HARDCOVER set a start date for The Wizard of Oz, and each came and went The Witch, Nikko, and another monkey. Stills of these sequences show stag- as preproduction problems grew. By October, director Norman ing and visual concepts that would not appear in the finished film: A Taurog had left the project; when filming finally started on the A • Rather than being followed and chased by The Winkies, Toto 13th, Richard Thorpe was—literally and figuratively—calling the shots. instead escaped through their ranks to leap across the castle $20.00 Rumor had it that the Oz Unit first would seek and photograph whichever drawbridge. California barnyard most resembled Kansas. Alternately, a trade paper re- • Thorpe kept Bolger, Ebsen, and Lahr in their Guard disguises well ported that all the musical numbers would be completed before other after they broke through The Tower Room door to free Dorothy. -

Hw Biography 2021

HUGH WOOLDRIDGE Director and Lighting Designer; Visiting Professor Hugh Wooldridge has produced, directed and devised theatre and television productions all over the world. He has taught and given master-classes in the UK, Europe, the US, South Africa and Australia. He trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) and made his West End debut as an actor in The Dame of Sark with Dame Celia Johnson. Subsequently he performed with the London Festival Ballet / English National Ballet in the world premiere production of Romeo and Juliet choreographed by Rudolph Nureyev. At the age of 22, he directed The World of Giselle for Dame Ninette de Valois and the Royal Ballet. Since this time, he has designed lighting for new choreography with dance companies around the world including The Royal Ballet, Dance Theatre London, Rambert Dance Company, the National Youth Ballet and the English National Ballet Company. He directed the world premieres of the Graham Collier / Malcolm Lowry Jazz Suite Under A Volcano and The Undisput’d Monarch of the English Stage with Gary Bond portraying David Garrick; the Charles Strouse opera, Nightingale with Sarah Brightman at the Buxton Opera Festival; Francis Wyndham’s Abel and Cain (Haymarket, Leicester) with Peter Eyre and Sean Baker. He directed and lit the original award-winning Jeeves Takes Charge at the Lyric Hammersmith; the first productions of the Andrew Lloyd Webber and T. S. Eliot Cats (Sydmonton Festival), and the Andrew Lloyd Webber / Don Black song-cycle Tell Me 0n a Sunday with Marti Webb at the Royalty (now Peacock) Theatre; also Lloyd Webber’s Variations at the Royal Festival Hall (later combined together to become Song and Dance) and Liz Robertson’s one-woman show Just Liz compiled by Alan Jay Lerner at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

March 11 - 21, 2021 Author Biographies

Calvary Theatre Arts Presents TheFantasticks Book and Lyrics by Music by TOM JONES HARVEY SCHMIDT March 11 - 21, 2021 Author Biographies Composer Harvey Schmidt and lyricist Tom Jones are the legendary writing team best known for shaping the American musical landscape with their 1960 hit, The Fantasticks. After its Off-Broadway opening in May 1960, it went on to become the longest-running production in the history of the American stage and one of the most frequently produced musicals in the world. Their first Broadway show, 110 in the Shade, was revived on Broadway in a new production starring Audra MacDonald. I Do! I Do!, their two-character musical starring Mary Martin and Robert Preston, was a success on Broadway and is frequently done around the country. For several years Jones and Schmidt worked privately at their theatre workshop, concentrating on small-scale musicals in new and often untried forms. The most notable of these efforts were Celebration, which moved to Broadway, and Philemon, which won an Outer Critics Circle Award. They contributed incidental music and lyrics to the Off-Broadway play Colette starring Zoe Caldwell, then later did a full-scale musical version under the title Colette Collage. The Show Goes On, a musical revue featuring their theatre songs and starring Jones and Schmidt, was presented at the York Theatre, and Mirette, their musical based on the award-winning children's book, was premiered at the Goodspeed Opera House in Connecticut. In addition to an Obie Award and the 1992 Special Tony Award for The Fantasticks, Jones and Schmidt were inducted into the Broadway Hall of Fame at the Gershwin Theatre, and on May 3, 1999 their 'stars' were added to the Off-Broadway Walk of Fame outside the Lucille Lortel Theatre. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

Eng Book2002

Author Title Place of Pub. Publisher Date ISBN London, Great Maugham, Somerset W. Encore Britain Heinemann 1951 Maugham, Somerset W. The Constant Wife New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1926/1927 Maugham, Somerset W. A Writer's Notebook New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1949 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House New York, US Stage and Screen 1997 Gentry, Curt J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets New York, US Norton 1991 Browning, John and Gentry, Curt John M. Browning American Gunmaker New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1964 Bennett, Cerf. A At Random the Reminiscences of Bennett Cerf New York, US Random House, INC. 1977 Ernest Hemingway By Line New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1956/1967 Hotchner A.E. Papa Hemingway New York, US Random House, INC. 1955/1966 Ernest Hemingway Islands in the Stream New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1970 Ernest Hemingway A Moveable Feast New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1964 Ernest Hemingway The Sun Also Rises New York, US Modern Library 1926 Ross, Lillian Portrait of Hemingway New York, US Simon and Schuster 1950/1961 W.W. Norton & Company, Gentry, Curt Frame-up New York, US INC 1967 London, Great Greene, Graham The Confidential Agent Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1939/1952 London, Great Greene, Graham Stamboul Train Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1932/1951 London, Great Greene, Graham A Burnt-Out Case Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1960/1961 Greene, Graham The 3rd Man New York, US The Viking Press 1949/1950 Wilder, Billy and Diamond, I.A.L. The Apartment and the Fortune Cookie New York, US Praeger 1971 Commander Hasting Japanese Letters: Eastern Impressions of London, Great Berkeley, R.N. -

Dept Web Forsythe Act-Dir

Eric Forsythe Acting Experience (See Key, below). Julius Caesar (Shakespeare) Brutus DC: 1966 (w/Charles Morey) Julius Caesar (Shakespeare) Trebonius PL&T: 1984 (Murphy Guyer) King Lear (Shakespeare) Lear DC: 1975 (Errol Hill) Henry V (Shakespeare) Exeter DC: 1967 Comedy of Errors (Shakespeare) Aegeon DC: 1968 (Don Marcus) Macbeth (Shakespeare) Banquo PL&T: 1985 (Murphy Guyer) Macbeth (Shakespeare) MacD’s Son/Bl. Child CSF: 1958 (Jason Robards) The Tempest (Shakespeare) Trinculo PL&T: 1980 Pericles (Shakespeare) Gower CMU: 1971 (Larry Carra) A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Shakes.) Oberon/Theseus MWVT: 1978 (Karen Trott) Twelfth Night (Shakespeare) Antonio PDG: 1980 (Paxton Whitehead) The Miser (Moliere) Harpagon DC: 1969 Tartuffe (Moliere) Tartuffe MWV: 1979 (David Strathairn) Tartuffe (Moliere) Tartuffe PL&T: 1982 Les Precieuses Ridicules (Moliere) Mascarille DC: 1969 Scapino! (Moliere/Dale/Dunlop) Geronte MWVT: 1978 (Marisa Smith) Prometheus Bound (Lowell) Prometheus PPC: 1972 Dennis Boutsikaris) An Enemy of the People (Ibsen) Mr. Vik DC: 1967 (Richmond Hoxie) The Seagull (Chekhov) Trigorin FT: 1981 Anatol (Schnitzler) Max CC: 1971 La Ronde (Schnitzler) Young Gent TLD: 1970 (Keith Michael) Arms and the Man (Shaw) Russian Officer. MWVT: 1979 (Mandy Carlin) St. Joan (Shaw) Polly/Courcelles McT: 1984 (Nagle Jackson) Augustus Does His Bit (Shaw) Augustus PL&T: 1980 Slasher and Crasher (Morton) Slasher DC: 1968 Charley’s Aunt (Thomas) Spettigue MWVT: 1976 (Jean Passanante) Eric Forsythe 1 The Pirates of Penzance (Gilbert/Sullivan) Major General UI: 1987 Patience (Gilbert/Sullivan) Bunthorne DC: 1968 The Sorceror (Gilbert/Sullivan) J.W. Wells DC: 1967 Yeoman of the Guard (G&S) Sgt. Meryll CMU: 1970 Cox and Box (Burnand & Sullivan) Cox DC: 1967 Cox and Box (Burnand/Sullivan) Sgt. -

MEMORY of the WORLD REGISTER the Wizard of Oz

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming 1939), produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer REF N° 2006-10 PART A – ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 1 SUMMARY In 1939, as the world fell into the chaos of war, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released a film that espoused kindness, charity, friendship, courage, fortitude, love and generosity. It was dedicated to the “young, and the young in heart” and today it remains one of the most beloved works of cinema, embraced by audiences of all ages throughout the world. It is one of the most widely seen and influential films in all of cinema history. The Wizard of Oz (1939) has become a true cinema classic, one that resonates with hope and love every time Dorothy Gale (the inimitable Judy Garland in her signature screen performance) wistfully sings “Over the Rainbow” as she yearns for a place where “troubles melt like lemon drops” and the sky is always blue. George Eastman House takes pride in nominating The Wizard of Oz for inclusion in the Memory of the World Register because as custodian of the original Technicolor 3-strip nitrate negatives and the black and white sequences preservation negatives and soundtrack, the Museum has conserved these precious artefacts, thus ensuring the survival of this film for future generations. Working in partnership with the current legal owner, Warner Bros., the Museum has made it possible for this beloved film classic to continue to enchant and delight audiences. The original YCM negatives have been conserved at the Museum since 1975, and Warner Bros. recently completed our holdings of the film by assigning the best surviving preservation elements of the opening and closing black and white sequences and the soundtrack to our care. -

Table of Contents

GEVA THEATRE CENTER PRODUCTION HISTORY TH 2012-2013 SEASON – 40 ANNIVERSARY SEASON Mainstage: You Can't Take it With You (Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman) Freud's Last Session (Mark St. Germain) A Christmas Carol (Charles Dickens; Adapted/Directed by Mark Cuddy/Music/Lyrics by Gregg Coffin) Next to Normal (Music by Tom Kitt, Book/Lyrics by Brian Yorkey) The Book Club Play (Karen Zacarias) The Whipping Man (Matthew Lopez) A Midsummer Night's Dream (William Shakespeare) Nextstage: 44 Plays For 44 Presidents (The Neofuturists) Sister’s Christmas Catechism (Entertainment Events) The Agony And The Ecstasy Of Steve Jobs (Mike Daisey) No Child (Nilaja Sun) BOB (Peter Sinn Nachtrieb, an Aurora Theatre Production) Venus in Fur (David Ives, a Southern Repertory Theatre Production) Readings and Festivals: The Hornets’ Nest Festival of New Theatre Plays in Progress Regional Writers Showcase Young Writers Showcase 2011-2012 SEASON Mainstage: On Golden Pond (Ernest Thompson) Dracula (Steven Dietz; Adapted from the novel by Bram Stoker) A Christmas Carol (Charles Dickens; Adapted/Directed by Mark Cuddy/Music/Lyrics by Gregg Coffin) Perfect Wedding (Robin Hawdon) A Raisin in the Sun (Lorraine Hansberry) Superior Donuts (Tracy Letts) Company (Book by George Furth, Music, & Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim) Nextstage: Late Night Catechism (Entertainment Events) I Got Sick Then I Got Better (Written and performed by Jenny Allen) Angels in America, Part One: Millennium Approaches (Tony Kushner, Method Machine, Producer) Voices of the Spirits in my Soul (Written and performed by Nora Cole) Two Jews Walk into a War… (Seth Rozin) Readings and Festivals: The Hornets’ Nest Festival of New Theatre Plays in Progress Regional Writers Showcase Young Writers Showcase 2010-2011 SEASON Mainstage: Amadeus (Peter Schaffer) Carry it On (Phillip Himberg & M. -

Little Theatre Society of Indiana

LITTLE THEATRE SOCIETY OF INDIANA 1915-16 1919-20 1921-22 Polyxena Bernice Release A Killing Triangle Eugenically Speaking The Dragon The Glittering Gate Three Pills in a Bottle The Spring The Scheming Lieutenant Trespass A Nativity Play Dad The Angel Intrudes The Constant Lover A Christmas Miracle Play Trespass (2nd Production) Androcles & the Lion The Pretty Sabine Women The Shepherd in the Distance The Forest Ring Overtones The Star of Bethlehem Beyond the Horizon The Broken God Dierdre of the Sorrows Everyman Dad (2nd Production) The Jackdaw The Betrothal Cake At Steinberg’s Bushido Disarmament How He Lied to Her Husband A Woman’s Honor The Casino Gardens The Game of Chess Unspoken Children of the Moon The Kisses of Marjorie Moonshine Belinda Dawn Phoebe Louise Not According to Hoyle The Dark Lady of the Sonnets The Bank Robbery Mansions A Scrambled Romance Chicane The Dryad & the Deacon (silent film) The Groove Underneath A Shakespeare Revel Stingy 1922-23 Rococo The Trysting Place 1916-17 The Price of Coal A Civil War Pageant 1920-21 The Turtle Dove Night with Indiana Authors The Proposal Brothers Polly of Pogue’s Run In Hospital Two Dollars, Please! Laughing Gas Behind a Watteau Picture The Marriage Gown The Lost Silk Hat The Home of the Free Dad (3rd Production) The Farce of Pierre Patelin The Blind Sycamore Shadders Duty The Medicine Show Nocturne The Maker of Dreams Aria Da Capo Treason The Importance of Being Mary Broome Where Do We Go From Here? Earnest The Star of Bethlehem (2nd The Wish Fellow Lithuania Production) Father and the Boys Supressed Desires The Mollusc My Lady Make-Believe Cathleen Ni’Hoolihan Mary’s Lamb A Shakespeare Revel (2nd Spreading the News The Emperor Jones Production) The Rising of the Moon The Beauty Editor Sham 1923-24 1917-18 The Confession March Hares (No records survive) The Lotion of Love The Bountiful Lady The Wren 1918-19 The Doctor of Lonesome Folk A Pageant of Sunshine Why Marry? and Shadow Hidden Spirits The Murderer (a.k.a. -

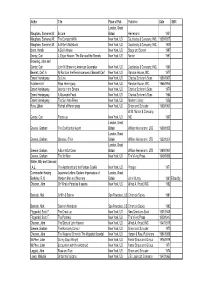

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images Can Be Accessed in the Indiana Room

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images can be accessed in the Indiana Room. Call (812)949-3527 for more information. Groom Bride Marriage Date Image Aaron, Elza Antle, Marion 8/12/1928 026-048 Abbott, Charles Ruby, Hallie June 8/19/1935 030-580 Abbott, Elmer Beach, Hazel 12/9/1922 022-243 Abbott, Leonard H. Robinson, Berta 4/30/1926 024-324 Abel, Oscar C. Ringle, Alice M. 1/11/1930 027-067 Abell, Lawrence A. Childers, Velva 4/28/1930 027-154 Abell, Steve Blakeman, Mary Elizabeth 12/12/1928 026-207 Abernathy, Pete B. Scholl, Lorena 10/15/1926 024-533 Abram, Howard Henry Abram, Elizabeth F. 3/24/1934 029-414 Absher, Roy Elgin Turner, Georgia Lillian 4/17/1926 024-311 Ackerman, Emil Becht, Martha 10/18/1927 025-380 Acton, Dewey Baker, Mary Cathrine 3/17/1923 022-340 Adam, Herman Glen Harpe, Mary Allia 4/11/1936 031-273 Adam, Herman Glenn Hinton, Esther 8/13/1927 025-282 Adams, Adelbert Pope, Thelma 7/14/1927 025-255 Adams, Ancil Logan, Jr. Eiler, Lillian Mae 4/8/1933 028-570 Adams, Cecil A. Johnson, Mary E. 12/21/1923 022-706 Adams, Crozier E. Sparks, Sarah 4/1/1936 031-250 Adams, Earl Snook, Charlotte 1/5/1935 030-250 Adams, Harry Meyer, Lillian M. 10/21/1927 025-376 Adams, Herman Glen Smith, Hazel Irene 2/28/1925 023-502 Adams, James O. Hallet, Louise M. 4/3/1931 027-476 Adams, Lloyd Kirsch, Madge 6/7/1932 028-274 Adams, Robert A.