Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of a National Institution Edited by Ida Audeh

Birzeit University: The Story of a National Institution Edited by Ida Audeh Birzeit University: The Story of a National Institution Editor: Ida Audeh All rights reserved. Published 2010 Birzeit University Publications Birzeit University: The Story of a National University Editor: Ida Audeh Arabic translation: Jumana Kayyali Abbas Photograph coordinator: Yasser Darwish Design: Palitra Design Photographs: Birzeit University archives; Institute of Community and Public Health archives Printing: Studio Alpha ISBN 978-9950-316-51-5 Printed in Palestine, 2010 Office of Public Relations P.O. Box 14 Birzeit, Palestine Tel.: + 97022982059 Fax: +97022982059 Email: [email protected] www.birzeit.edu Contents Foreword Chapter 4. An Academic Biography Nabeel Kassis ............................................................................................... VII Sami Sayrafi ...................................................................................................35 Exploring the Palestinian Landscape, by Kamal Abdulfattah ................... 40 Preface “The Past Is in the Present”: Archeology at Birzeit, by Lois Glock ........... 40 Hanna Nasir ..................................................................................................IX My Birzeit University Days, 1983-85, by Thomas M. Ricks ...................... 42 Acknowledgments .........................................................................................XI Chapter 5. Graduate Studies at Birzeit George Giacaman .........................................................................................45 -

I II .-C -C a Manual for Q) ::E Palestinian Policymakers Q) and Media -••••= Professionals Q) 'C-':: Q) ~ -~ -C:: 0 •••• 3= 0 ::I

-II II .-c -c A Manual for Q) ::E Palestinian Policymakers Q) and Media -••••= Professionals Q) 'c-':: Q) ~ -~ -c:: 0 •••• 3= 0 ::I:: Jerusalem Media and Communication Center July 2005 Jerusalem Media & Communication Centre July 2005 All Rights Reserved PREPARED BY Charmaine Seitz DESIGN JMCC PRINT Abu Ghosh Press 02-2989475 Information in this repolt may be quoted providing full credit is given to the Jerusalem Media & Communication Centre (JMCC). No palt of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature, without the prior written permission of the JMCC. Jerusalem JMCC was established in 1988 by a group of Media & Palestinian journalists and researchers to provide Communication information on events in the West Bank (including Center, JMCC East Jerusalem) and Gaza Strip. JMCC's Jerusalem and Ramallah offices provide important political documents related to the Palestinian cause such as, agreements, decisions, and correspondence for Palestinian and Arabic readers. The Center provides a variety of services to journalists, researchers, interested individuals, international agencies and organizations such as News Services, Daily Press Summary, TV Production, Public Opinion Polls, Marketing Research, and special reports on issues such as Water, Law, Economics and Politics. Tn addition, it arranges itineraries and accompanies film crews, journalists and delegations on fact-finding visits to the West Bank and -

Tkfikpi Vjg )Cr Dgvyggp 4Gugctej Cpf 2Qnke[ /Cmkpi Kp Vjg 2Cnguvkpkcp

Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute The Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) Founded in Jerusalem in 1994 as an independent, non-profit institution to contribute to the policy-making process by conducting economic and social policy research. MAS is governed by a Board of Trustees consisting of prominent academics, businessmen and distinguished personalities from Palestine and the Arab Countries. Mission MAS is dedicated to producing sound and innovative policy research, relevant to economic and social development in Palestine, with the aim of assisting policy-makers and fostering public participation in the formulation of economic and social policies. Strategic Objectives Providing a forum for free, open and democratic public debate among all stakeholders on the socio-economic policy-making process. Disseminating up-to-date socio-economic information and research results. Providing technical support and expert advice to PNA bodies, the private sector, and NGOs to enhance their engagement and participation in policy formulation. Strengthening economic and social policy research capabilities and resources in Palestine. Board of Trustees Ghania Malhees (Chairman), Samer Khoury (Vice chairman), Ghassan Khatib (Treasurer), Luay Shabaneh (Secretary), Nabil Kaddumi, Heba Handoussa, George Abed, Raja Khalidi, Rami Hamdallah, Radwan Shaban, Taher Kanaan, Sabri Saidam, Samir Huleileh, Numan Kanafani (Director General). Copyright © 2009 Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) P.O. Box 19111, Jerusalem and P.O. Box 2426, Ramallah Tel: ++972-2-2987053/4, Fax: ++972-2-2987055, e-mail: [email protected] Web Site : http://www.mas.ps Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute Bridging the Gap between Research and Policy Making in the Palestinian Territories: A Stakeholders’ Analysis Researcher: Joseph DeVoir, Research Associate at MAS. -

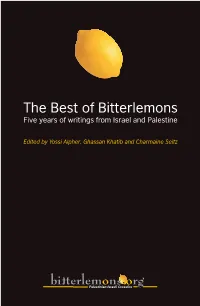

Bitterlemons Layout1.Indd

The Best of Bitterlemons Five years of writings from Israel and Palestine Edited by Yossi Alpher, Ghassan Khatib and Charmaine Seitz Palestinian-Israeli Crossfire The Best of Bitterlemons Five years of writings from Israel and Palestine edited by Yossi Alpher, Ghassan Khatib and Charmaine Seitz Table of Contents Preface 11 Palestinian Forward 13 Israeli Forward 15 1. Land 17 The green line as past and future boundary David Newman 17 The ghostly green line Ihab Abu Ghosh 19 It would bring about a terrible response a conversation with Ephraim Sneh 22 The Sharon line Yisrael Harel 24 Settlements plus Ghassan Khatib 26 Only think of us as human Sharif Omar 28 Israel’s interests take primacy a conversation with Dore Gold 30 Tearing down the walls Samah Jabr 32 2. Identity & Culture 35 Copyright © by bitterlemons.org, bitterlemons-international.org Coming to terms and bitterlemons-dialogue.org Yossi Alpher 35 The long journey to two demands All Rights Reserved Adel Manna 38 Printed in Jerusalem, 2007 Human misery comes from human mistakes a conversation with Ahmad Yassin 40 Reflections of a Jerusalem Christian ISBN: 978-965-555-285-0 George Hintlian 43 Turbo Design Turbo Touching the core: The politics of narrative on the Temple Mount/ Solving the refugee problem Haram al-Sharif Daniel Seidemann 45 Yossi Beilin 80 The broken boundaries of statehood and citizenship Sari Hanafi 83 3. History 49 Zionism & the Israeli-Palestinian conflict Shlomo Avineri 49 6. Leadership & Strategy 87 The Palestinian narrative clashes with a two-state solution Arafat -

The Situation of Workers of the Occupied Arab Territoriespdf

REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR-GENERAL APPENDIX The situation of workers of the occupied Arab territories INTERNATIONAL LABOUR CONFERENCE 104th SESSION, 2015 ILC.104/DG/APP International Labour Conference, 104th Session, 2015 Report of the Director-General Appendix The situation of workers of the occupied Arab territories International Labour Office, Geneva ISBN 978-92-2-129001-8 (print) ISBN 978-92-2-129002-5 (Web pdf) ISSN 0074-6681 First edition 2015 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. ILO publications can be obtained through major booksellers or ILO local offices in many countries, or direct from ILO Publications, International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. Catalogues or lists of new publications are available free of charge from the above address, or by email: [email protected]. Visit our website: www.ilo.org/publns. Formatted by TTE: Confrep-ILC104(2015)-DG_APPENDIX_[CABIN-150416-1]-En.docx Printed by the International Labour Office, Geneva, Switzerland Preface In accordance with the mandate given by the International Labour Conference, I again sent a mission to prepare a report on the situation of workers of the occupied Arab territories. -

Corruption in the Palestinian Authority: Neo-Patrimonialism, the Peace Process and the Absence of State-Hood

Durham E-Theses CORRUPTION IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY: NEO-PATRIMONIALISM, THE PEACE PROCESS AND THE ABSENCE OF STATE-HOOD FANGALUA, LUCIANE,FUEFUE-O-LAKEPA How to cite: FANGALUA, LUCIANE,FUEFUE-O-LAKEPA (2012) CORRUPTION IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY: NEO-PATRIMONIALISM, THE PEACE PROCESS AND THE ABSENCE OF STATE-HOOD, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3615/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 CORRUPTION IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY: NEO-PATRIMONIALISM, THE PEACE PROCESS AND THE ABSENCE OF STATE-HOOD Luciane Fuefue-‘o-Lakepa Fangalua THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS 2012 CORRUPTION IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY: NEO-PATRIMONIALISM, THE PEACE PROCESS AND THE ABSENCE OF STATE-HOOD ABSTRACT The thesis examines the practice of corruption in the Palestinian Authority (PA) from the period of its establishment until the death of Arafat. -

Mapping Palestinian Politics Provides an Interactive Overview of the Main Palestinian Political Institutions and Players in Palestine, Israel, and the Diaspora

MichaelPlutchok via Wikimedia Commons , CC BY - SA 3.0 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. Geography ........................................................................................................................... 4 Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) ................................................................................... 5 Palestinian citizens of Israel................................................................................................... 6 Joint List ............................................................................................................................. 6 Islamic Movement (Northern Branch) ............................................................................... 6 High Follow-Up Committee ............................................................................................... 7 Jerusalem ............................................................................................................................... 7 Refugee camps ....................................................................................................................... 7 3. Institutions ......................................................................................................................... 8 Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) .............................................................................. 8 Palestinian National Council (PNC) .................................................................................. -

1 1. Introduction

MichaelPlutchok via Wikimedia Commons , CC BY - SA 3.0 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. Geography ........................................................................................................................... 4 Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) ................................................................................... 5 Palestinian citizens of Israel................................................................................................... 6 Joint List ............................................................................................................................. 6 Islamic Movement (Northern Branch) ............................................................................... 6 High Follow-Up Committee ............................................................................................... 7 Jerusalem ............................................................................................................................... 7 Refugee camps ....................................................................................................................... 7 3. Institutions ......................................................................................................................... 8 Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) .............................................................................. 8 Palestinian National Council (PNC) .................................................................................. -

The Future Israeli - Palestinian Relationship

THE FUTURE ISRAELI - PALESTINIAN RELATIONSHIP A Concept Paper Prepared By The Joint Working Group On Israeli - Palestinian Relations Moshe Ma'oz Ghassan Khatib Ibrahim Dakkak Yossi Katz, MK Yezid Sayigh Ze’ev Schiff Shimon Shamir Khalil Shikaki Edited by Herbert C. Kelman Program on International Conflict Analysis and Resolution Weatherhead Center for International Affairs Harvard University December 1999 Abstract In this concept paper, the Joint Working Group on Israeli-Palestinian Relations – a group of influential Palestinians and Israelis that has been meeting periodically since 1994 to discuss final-status issues in the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations – explores the future relationship between the two societies after the signing of a peace agreement. The paper considers a relationship based on total separation between the two societies and states as neither realistic nor desirable. Instead, it envisages a future relationship based on mutually beneficial cooperation in many spheres, conducive to stable peace, sustainable development, and ultimate reconciliation. The basis for such a relationship must be laid in the process and outcome of the final-status negotiations and in the patterns of cooperation established on the ground. Efforts at cooperation and reconciliation cannot be pursued apart from their political context. The paper argues that the only feasible political arrangement on which a cooperative relationship can be built is a two-state solution, establishing a genuinely independent Palestinian state alongside of Israel. The resolution of final-status issues must be consistent with the sovereignty, viability, and security of both states. The paper then proceeds to describe several models for the relationship between the two states and societies.